Life After Being Defined By Violence

When violence becomes the thing everyone remembers, the future often disappears from view. The world focuses on the moment, the trial, the shock, and then moves on. But the person at the center of it still has years ahead of them, years shaped by consequences, supervision, reflection, and the slow attempt to build something resembling normal life again. Understanding that quieter chapter helps reveal a fuller picture, not just of what happened, but of what comes after when a life has already been permanently marked.

The Verdict That Changed His Entire Future

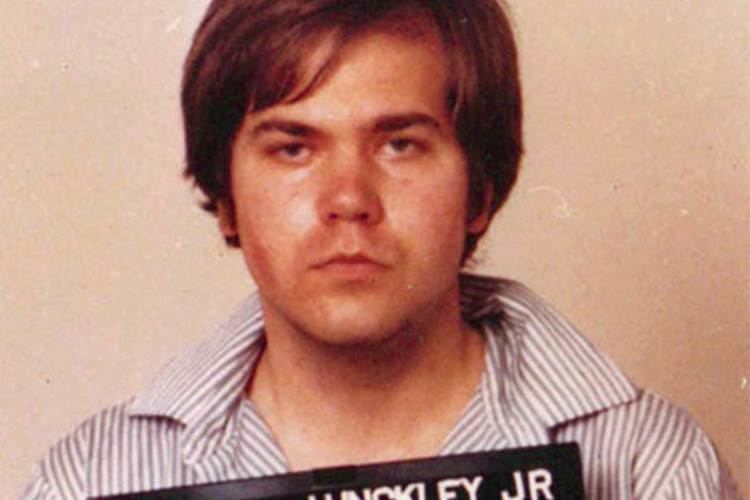

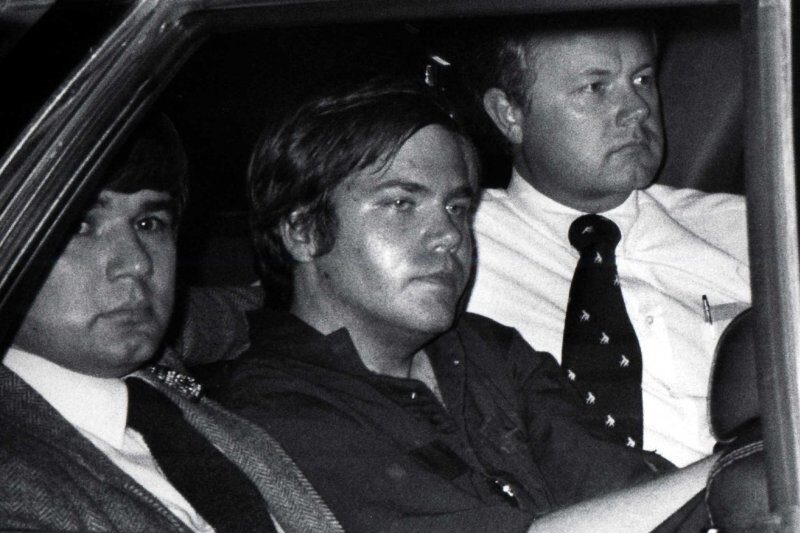

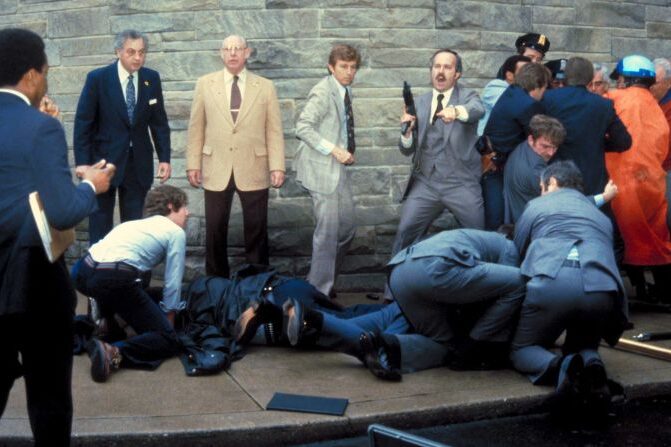

Most people remember the shocking shooting in 1981, but fewer remember the strange courtroom ending that quietly shaped everything that came after. In 1982, John Hinckley Jr. was found not guilty by reason of insanity, which meant the court believed severe mental illness drove his actions. Instead of prison, he was sent to St. Elizabeths psychiatric hospital in Washington for treatment under federal supervision. The decision stunned the public and sparked emotional debate, but for Hinckley himself it meant stepping into a locked medical world where doctors, not guards, controlled daily life and where freedom would depend on long term psychiatric stability rather than a fixed sentence.

From the moment he arrived, his future stopped being measured in years and started being measured in progress reports, therapy sessions, and court evaluations. The hospital was not temporary holding. It became the place where his adult life would unfold for decades. Every behavior, every conversation, every medication response would be documented. The long story of what happened to him after the shooting really begins here, not with the crime itself, but with this quiet legal decision that turned punishment into treatment and started one of the slowest monitored recoveries in modern American legal history.

Learning The Slow Rhythm Of Hospital Life

Once inside St. Elizabeths, Hinckley entered a routine that felt almost frozen in time. Days were structured around therapy meetings, medication reviews, supervised activities, and observation from psychiatric staff who tracked mood, sleep, and interaction patterns. Federal psychiatric hospitals operate with careful documentation because every small behavior may later influence court decisions. Early reports described him as withdrawn but cooperative, someone who followed instructions even while struggling emotionally. Life there was less about dramatic breakthroughs and more about slow stabilization, the kind that builds quietly over years rather than weeks.

For Hinckley, the hospital quickly stopped feeling like a temporary placement and started feeling like the entire world. Meals came on schedule, movement required permission, and progress meant consistency rather than speed. Patients lived under constant professional watch, which shaped habits and daily structure. This environment slowly trained him into predictable routines that doctors hoped would reduce obsessive thinking and emotional instability. What outsiders saw as confinement, the treatment team framed as long term psychiatric management. The rhythm was repetitive, controlled, and cautious, setting the foundation for every later decision about whether he could ever safely function beyond those hospital walls.

Early Requests For Freedom Were Firmly Rejected

Not long after treatment began, legal teams started testing the possibility of small privileges outside the hospital. These requests were cautious, asking for supervised outings or reduced restrictions, but judges rejected them repeatedly throughout the 1980s. The crime involved a sitting president, and officials were extremely wary of moving too quickly. Prosecutors argued that even minor freedoms could pose unacceptable risk, while public opinion remained deeply hostile. Each denial reinforced the idea that this would not be a short psychiatric stay followed by release. The system wanted overwhelming proof of long lasting stability before even considering change.

For Hinckley, those early refusals created a harsh reality check. Improvement alone was not enough. He needed years of documented safe behavior, not months. Each hearing meant more psychiatric testimony, more reports, and more waiting. The process showed how forensic mental health cases move at a deliberately slow pace, especially when national trauma is involved. Instead of counting down toward a release date, his life inside the hospital became open ended. Freedom was not tied to time served. It depended entirely on whether doctors and courts could one day agree that his mental condition truly remained stable under pressure.

First Carefully Supervised Trips Outside

By the early 1990s, doctors finally felt confident enough to recommend limited supervised outings beyond hospital grounds. These were tightly controlled clinical exercises rather than casual trips. Staff escorted him, planned the schedule minute by minute, and documented behavior afterward in detail. The goal was simple but important. Officials wanted to observe whether he could handle ordinary surroundings without emotional instability. Each successful outing became part of his growing medical record, showing how he reacted to small doses of independence after years of institutional living.

These early trips carried enormous weight even though they seemed small from the outside. Walking through a public space, eating outside hospital walls, or riding in a supervised vehicle all became measurable tests of real world functioning. Hinckley reportedly followed rules carefully and returned without incident, which slowly built professional confidence. In forensic psychiatry, consistent calm behavior matters more than dramatic improvement. These outings marked the first real shift in his long confinement story. They suggested that after years of strict institutional structure, doctors were beginning to test whether the outside world could slowly become part of his life again.

Structured Visits To His Parents’ Home

Eventually, the court allowed supervised visits to his parents’ home, which became one of the most important stages in his gradual transition. Family environments often reveal emotional responses that hospitals cannot fully simulate, so psychiatrists viewed these visits as serious evaluation opportunities rather than privileges. Schedules remained strict, movements monitored, and therapy compliance required throughout each stay. Reports suggested he behaved appropriately, maintained medication routines, and showed no signs of aggressive instability. These consistent results strengthened the argument that he could function safely in a structured domestic setting.

For the legal system, the parents’ home represented something valuable. It offered supervision, familiarity, and emotional stability in one place. Judges often look for exactly this type of controlled living arrangement before considering any broader release. Over time, repeated successful home visits built a practical bridge between institutional confinement and potential community living. Without such a stable family environment, many forensic patients remain hospitalized far longer. In Hinckley’s case, those quiet monitored stays at home slowly shifted the conversation from whether he could ever leave the hospital to how that transition might eventually be managed safely.

Public Anger Never Fully Disappeared

Even as medical reports grew more positive, public reaction to Hinckley’s possible freedoms remained tense. Every court hearing revived memories of the original shooting, and media coverage often reignited emotional debate. Many Americans believed any relaxation of restrictions felt wrong given the historic seriousness of the crime. Advocacy voices frequently spoke out, urging judges to remain extremely cautious. This atmosphere meant that decisions about his treatment unfolded under a level of national attention that most psychiatric cases never experience.

For judges, this created a delicate balancing act. Legal standards required decisions based on psychiatric evidence and current risk, not public anger, yet ignoring public concern entirely could damage confidence in the justice system. As a result, the court moved slowly and demanded unusually strong medical documentation before approving each step. For Hinckley, this meant his progress always happened under the shadow of the past. Even successful therapy and stable behavior did not guarantee quick approval. The emotional weight of the original event followed every evaluation, ensuring that any movement toward greater independence would remain cautious, measured, and heavily scrutinized.

First Limited Time Without Direct Escort

After many years of supervised outings, Hinckley eventually received permission for limited unsupervised time outside institutional oversight. This stage represented one of the most serious trust tests in his entire recovery process. Without staff physically present, responsibility shifted fully onto his own compliance with rules and schedules. Courts imposed detailed travel limits, reporting requirements, and time restrictions. Authorities tracked whether he followed every instruction exactly as ordered. Each successful outing added measurable proof that independence did not automatically trigger instability.

These moments may have appeared small to the public, but legally they carried enormous significance. Demonstrating reliability without direct supervision is often the final clinical threshold before broader release consideration. Reports indicated he returned on time, followed conditions, and avoided problematic situations. In forensic psychiatry, consistent safe performance during unsupervised exposure often weighs more heavily than years of controlled institutional behavior. These successful independent outings quietly strengthened the argument that hospital confinement might not need to remain permanent. The idea of structured community living slowly shifted from theoretical possibility to something judges could realistically evaluate.

His Parents’ House Becomes The Transition Plan

As unsupervised visits increased, his parents’ Virginia home gradually became the central plan for long term transition. Courts viewed the residence as stable, predictable, and supportive, with family members willing to help maintain structure. Living with relatives offered both emotional familiarity and an added layer of informal supervision, which reassured officials assessing public safety risk. During extended stays, strict rules still applied, including therapy attendance, movement reporting, and communication limitations. Reports continued showing full compliance, which steadily strengthened the credibility of the arrangement.

In many forensic cases, release depends less on the patient alone and more on whether a reliable living environment exists. The parents’ home provided exactly that. Over time, successful stays there demonstrated that he could function within ordinary household routines rather than institutional schedules. This evidence proved critical during later hearings. Judges prefer practical real world proof over theoretical psychiatric predictions. The quiet stability of that domestic setting helped shift his case from indefinite hospital commitment toward a structured community living plan that courts could realistically approve without feeling they were taking uncontrolled risks.

Media Silence Was Part Of The Recovery Plan

Throughout most of his confinement and early release years, strict rules limited Hinckley’s contact with journalists or public media platforms. Officials believed excessive publicity could risk encouraging unhealthy attention seeking or emotional stress linked to his earlier obsession with public recognition. Even when other freedoms expanded, media interaction usually required direct approval. The recovery strategy emphasized routine, privacy, and psychological stability rather than public storytelling. Authorities wanted his daily focus centered on treatment, family life, and structured habits instead of national attention.

This media silence kept his progress largely invisible to the public for many years. While headlines occasionally resurfaced during hearings, his everyday life unfolded quietly behind clinical supervision. From a psychiatric perspective, this low profile approach reduced external pressure and allowed rehabilitation to develop without constant outside reaction. For Hinckley personally, it meant living mostly outside the national spotlight that once defined him. The rule may have seemed restrictive, but professionals often consider controlled visibility essential in high profile forensic cases, where sudden public attention can complicate emotional stability and disrupt carefully managed long term treatment progress.

Music Slowly Became His Daily Escape

Somewhere during those long hospital years, music quietly entered Hinckley’s routine and stayed there. What started as something to pass the time slowly turned into a steady personal outlet. He practiced guitar, worked on simple melodies, and spent hours writing lyrics that reflected loneliness, regret, and everyday thoughts. Therapists often encourage creative hobbies because they help patients process emotion in safe ways, and in his case the structure of practicing songs gave his days a sense of direction. Inside an environment where most choices were controlled, music became one small space that felt personal.

Over time, this habit grew stronger and followed him beyond the hospital walls. Staff reports suggested he spent long stretches focused calmly on songwriting, which reinforced the idea that quiet creative work helped maintain emotional balance. Music was not treated as a career plan back then. It was simply something steady and grounding. Yet in hindsight, this small creative routine became one of the few continuous threads connecting his institutional life with the outside world he would later reenter, giving him something familiar to hold onto as everything else slowly changed.