1. The Gecko Who Stayed

Some commercials quietly become part of daily life, and GEICO’s gecko did exactly that after debuting in 1999. The animated character was created to clarify the company name, not to become a mascot for decades. Multiple voice actors have portrayed the gecko over time, each paid under contract with no lifetime royalties. Despite public assumptions, the role offered steady professional income rather than extraordinary wealth. The gecko’s endurance reflects brand strategy, not performer windfall. It sets the tone for how many long running ads work. Familiarity grows. Contracts renew. Faces change. The ad stays while the people behind it move on.

2. Flo and Financial Stability

Progressive introduced Flo in 2008 as a temporary character, but audience response changed everything. Actress Stephanie Courtney was hired as a salaried spokesperson, not a one time performer. Over time, she earned a reported high six figure annual income during active campaign years. Unlike earlier advertising eras, this role provided ongoing compensation tied to continued use. Flo’s success came from consistency and tone rather than spectacle. The character made insurance feel approachable. Courtney benefited from steady work in an unpredictable industry. While not an ownership role, it represents one of the clearer examples of long term advertising employment translating into real financial stability for a performer.

3. Mayhem and Measured Pay

Allstate introduced Mayhem in 2010 to personify everyday accidents, played by actor Dean Winters. The campaign ran consistently for years, but compensation followed standard spokesperson contracts, not open-ended profit sharing. Winters earned strong recurring pay while the ads aired, but no lifetime earnings beyond contract renewals. His visibility increased significantly, helping revive his broader acting career. The character worked because it reflected common experiences with humor and restraint. Mayhem felt familiar, not exaggerated. The role offered reliability rather than excess. It demonstrates how modern advertising can support a career without creating unrealistic financial outcomes for the performers involved.

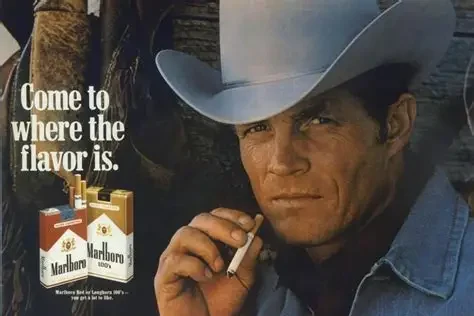

4. The Marlboro Man Reality

The Marlboro Man was portrayed by several models and actors from the 1950s through the 1990s. None were permanent brand representatives. Most were paid per shoot or short-term contracts, often modestly. Contrary to popular belief, there was no long term financial security attached. The campaign focused on image, not individual identity. Some models later spoke about public recognition without compensation to match. The brand became iconic while the performers remained replaceable. This campaign reflects early advertising practices where longevity benefited corporations far more than contributors. The cowboy image endured. The men behind it quietly returned to ordinary lives once the work ended.

5. Where’s the Beef Actually Went

Clara Peller delivered Wendy’s famous “Where’s the beef?” line in 1984, becoming instantly recognizable. She was paid a flat fee for her appearances, with no residuals attached. At the time, commercial actors rarely received long term compensation. Despite the slogan’s massive success and cultural impact, Peller’s earnings remained limited. She later confirmed that fame did not translate into wealth. The campaign boosted Wendy’s brand identity but not the financial standing of its star. Her experience reflects a period when advertising moved faster than performer protections. The line lived on. The paycheck ended when the contract did.

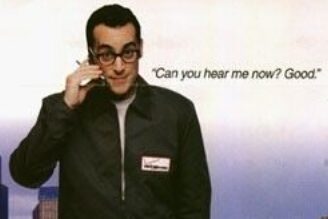

6. Can You Hear Me Clearly

Paul Marcarelli became Verizon’s spokesperson in 2002, appearing in the role for nearly a decade. He was paid through renewable contracts that reportedly totaled several million dollars over time. While financially meaningful, the role did not include ownership or perpetual royalties. His association with the brand became so strong that leaving required rebuilding his public identity. When he later appeared in ads for a competitor, it drew widespread attention. The campaign delivered stability and recognition, but also typecasting challenges. His story shows how long running ads can support a career while quietly limiting creative freedom beyond the brand itself.

7. Tony the Tiger’s Voice

Tony the Tiger debuted in 1952, voiced most famously by Thurl Ravenscroft. Ravenscroft was paid as a professional voice actor under the standards of his era, receiving session fees rather than royalties. The character became globally recognized, but compensation did not grow alongside that recognition. At the time, mascots were considered company property, not collaborative creations. Ravenscroft continued working steadily in voice acting, benefiting from consistency rather than wealth. Tony’s longevity illustrates how early advertising valued reliability over performer equity. The cereal brand thrived for generations. The voice behind it earned respectable work, but not enduring financial rewards tied to the character.

8. The Budweiser Frog Facts

Budweiser’s frogs appeared prominently in the mid 1990s as part of a short but memorable campaign. The voices were provided by professional actors paid per recording session. There were no royalties or long-term contracts tied to the characters. Once the campaign ended, so did the income. While the frogs became pop culture shorthand for the brand, the performers remained anonymous. This campaign demonstrates how even highly recognizable ads can offer only temporary benefit to those involved. Cultural impact and financial outcome often diverge in advertising. The frogs croaked briefly, left an impression, and then quietly disappeared along with the paychecks.

9. Jake Before the Upgrade

The original Jake from State Farm was played by Jake Stone, an actual company employee, in 2011. He received his regular salary and minor bonuses, not actor compensation. When the campaign expanded, the role was recast with professional actor Kevin Miles under a traditional spokesperson contract. Miles earned significantly more due to the campaign’s scope. Stone returned to his normal role at the company. This change highlights how brands reassess value once popularity becomes clear. Same character. Same name. Completely different outcomes. Timing mattered more than visibility. The ad evolved, and compensation evolved with it for the person who arrived later.

10. The Owl and the Licks

The Tootsie Pop owl appeared in a 1970 commercial that became one of the most replayed ads in history. Voice actor Paul Winchell performed the role for a standard session fee. There were no residuals, as the industry did not anticipate long term reuse. The commercial’s longevity surprised everyone involved. While the owl became embedded in childhood memory, Winchell’s compensation remained fixed. He later described it as routine work at the time. This ad reflects how advertising history often outpaces its contracts. A small recording session became a permanent cultural reference without changing the financial reality for its creator.

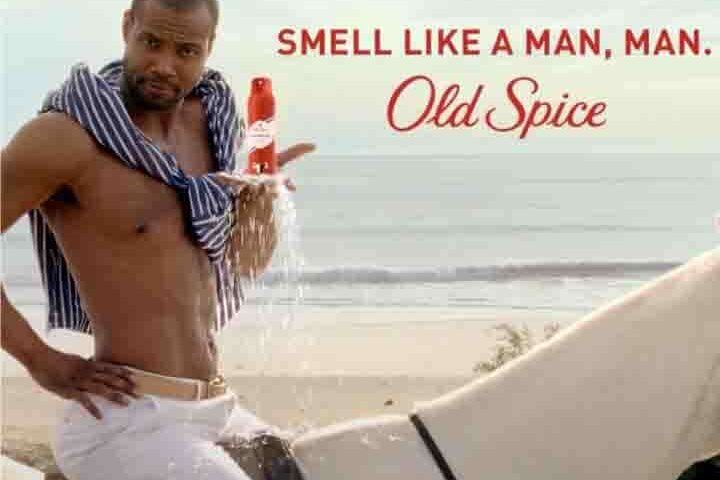

11. Old Spice and Sudden Fame

The Old Spice campaign featuring Isaiah Mustafa launched in 2010 and ran intensely for a short period. Unlike decades long mascots, this campaign relied on saturation rather than longevity. Mustafa earned a strong but time limited salary tied to the campaign’s duration. There were no lifetime royalties. The role significantly boosted his visibility, leading to broader acting opportunities. While not a forever ad, its cultural impact was immediate. This example shows how advertising success can come quickly and fade just as fast. The financial benefit came through exposure and subsequent work, not ongoing payments from the commercials themselves.

12. The Burger King Mask

The masked Burger King character appeared intermittently from the 1970s through the late 2000s, portrayed by multiple performers. Actors were paid under costume performance agreements with no public credit or long-term compensation. The anonymity was intentional. When the campaign ended, performers moved on without recognition or residuals. The character’s unsettling familiarity worked for the brand but offered little personal gain. This type of advertising emphasizes concept over individual contribution. The mask mattered more than the person inside. It demonstrates how some long running campaigns erase identity entirely while still benefiting from repeated exposure and audience memory.

13. Campbell’s Kids Truth

The Campbell’s Soup children appeared in commercials during the 1990s and early 2000s, portraying warmth and family comfort. Child actors were paid standard industry rates with earnings managed through guardians and trust accounts. There were no residuals once the ads stopped airing. Contrary to assumptions, most did not receive significant long-term income. The commercials worked because they felt relatable and sincere. For the families involved, it was temporary work rather than lasting security. This reflects how family-oriented advertising often prioritizes emotion overcompensation. The memory of the ad lasted far longer than the financial benefit for those who appeared in it.

14. Inside the Energizer Bunny

The Energizer Bunny debuted in 1989 and has been portrayed by multiple performers over time. Actors inside the costume were paid per appearance under union guidelines. The character belonged entirely to the brand, not the performer. No single individual benefited long term from the role. The Bunny’s endurance symbolized energy, not career longevity. As performers changed, the audience never noticed. This campaign shows how mascots are designed to outlast people. The work provided fair pay and consistency during contracts, but no enduring financial connection. The Bunny kept going. The actors rotated quietly without recognition or lasting attachment to the character.

15. The Jingle That Stayed

The Oscar Mayer Wiener song first aired in 1962 and continued appearing in various forms for decades. The original child performer was paid a one time fee, which was standard for commercials at the time. As the song became a cultural staple, it was rerecorded with different children rather than reused for royalties. The jingle’s simplicity helped it endure across generations, even as faces and voices changed. The brand benefited from nostalgia and repetition, while performers received short term compensation only. This ad shows how sound and familiarity can carry longevity without relying on a single recognizable person over time.

16. The Verizon Test Families

Verizon often featured everyday families testing phones and services during the early expansion of its coverage campaigns. These participants were typically paid as commercial extras or short-term actors, not long-term spokespeople. Compensation varied by shoot but stayed within standard advertising rates. None received residuals after airing. Viewers sometimes assumed the families were employees or long-term partners, but most appeared only briefly. The campaign’s credibility came from relatability rather than familiarity. These ads remind us that many long running campaigns rely on rotating ordinary faces. The brand remains consistent while individuals appear once, get paid, and quietly return to everyday life afterward.

17. The Dell Dude Boom

The Dell Dude became famous in the late 1990s as personal computers entered more homes. Actor Ben Curtis was hired as a spokesperson and quickly became recognizable. His pay grew as the campaign expanded, reportedly reaching strong six figure earnings annually during peak years. However, the role ended abruptly following personal controversy, and compensation stopped immediately. The experience showed how advertising fame can be fragile. While the role brought visibility and income, it also tied his public image tightly to the brand. Once Dell moved on, Curtis had to rebuild his career without the commercial safety net that once seemed permanent.

18. The Toys “R” Us Kid

Geoffrey the Giraffe fronted Toys “R” Us ads for decades, but the children who appeared alongside him changed constantly. Each child actor was paid per appearance under standard child labor agreements. There were no long-term contracts or royalties tied to repeat airings. Many grew up surprised to learn the commercials remained popular long after filming. The mascot carried continuity while human participants rotated. This structure protected the brand but limited performer benefit. It reflects a common advertising approach where characters endure, and people pass through briefly. Childhood memories stayed strong. Financial outcomes stayed modest and temporary for those involved.

19. The McDonald’s Happy Faces

McDonald’s commercials frequently featured smiling families and children enjoying meals. These actors were typically hired for single campaigns with fixed fees. No residuals followed once the ads stopped airing. Despite the brand’s massive scale, performers did not share in its ongoing success. Many later recalled the experience as fun but brief. The familiarity of the ads came from repetition of themes, not faces. McDonald’s perfected a formula where warmth felt personal while casting remained interchangeable. The result was a sense of connection without long term attachment. These ads show how consistency can be built without rewarding individual contributors beyond the initial job.