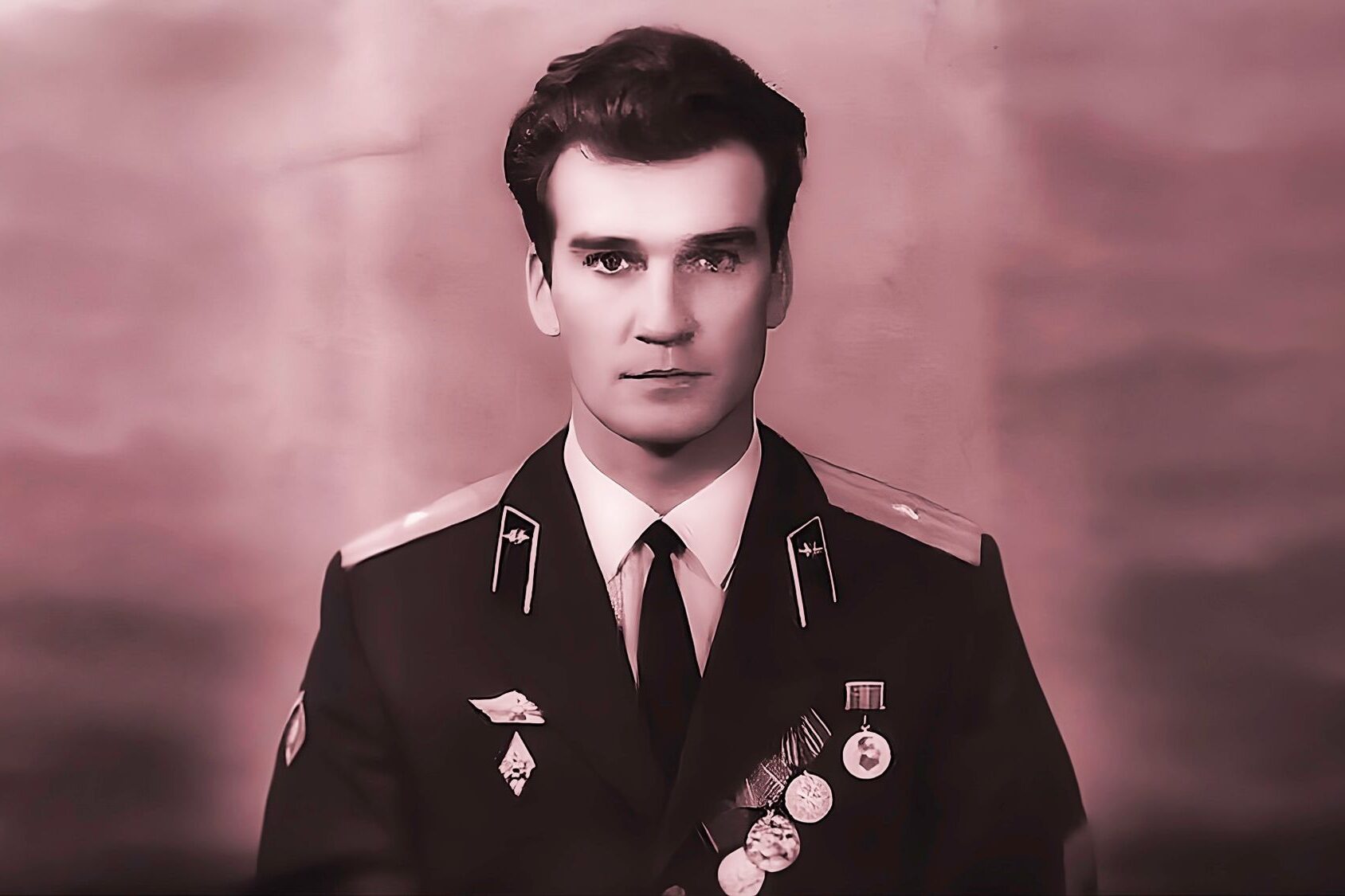

1. Stanislav Petrov Trusted His Instinct

In September 1983, the Cold War sat quietly on edge, and most people had no idea how close things came. That context matters here. Stanislav Petrov was a Soviet lieutenant colonel assigned to monitor early warning systems for incoming nuclear attacks. One night, alarms flashed that the United States had launched missiles toward the Soviet Union. Procedure required immediate escalation. Petrov hesitated. He reasoned that a real attack would involve more missiles. He logged it as a false alarm. His judgment prevented retaliation. At the time, his decision was treated as a procedural failure, not heroism, and the incident stayed buried.

Years later, investigations confirmed the system malfunctioned due to sunlight reflecting off clouds. Petrov later explained that logic and instinct guided him, not certainty. He said he was simply doing his job. His warning came through restraint, not reporting. It was never formally rewarded, and for decades it was barely acknowledged. Today, his choice stands as a reminder that warnings are not always loud. Sometimes they appear as quiet pauses when systems demand speed. Petrov showed that listening to doubt can be as important as following protocol.

2. Ignaz Semmelweis Was Dismissed By His Peers

In the 1840s, Ignaz Semmelweis worked as a doctor in Vienna, watching women die from childbed fever at alarming rates. He noticed that physicians moved directly from autopsies to childbirth without cleaning their hands. When he required handwashing with chlorinated water, death rates dropped sharply. Semmelweis warned colleagues repeatedly, presenting clear results. Instead of acceptance, he faced ridicule. Many doctors believed disease could not be transmitted by touch. His warnings challenged their authority and habits, and that resistance proved stronger than evidence.

Semmelweis grew increasingly frustrated as his findings were ignored. He wrote openly that doctors were responsible for preventable deaths, which further alienated him. Eventually, he lost his position and credibility. Germ theory had not yet been accepted, and his work was shelved. Semmelweis died before his ideas were validated. Today, hand hygiene is foundational to medicine. His story shows how warnings backed by results can still be rejected when they disrupt professional pride. Being right was not enough. Timing and willingness to listen mattered just as much.

3. Roger Boisjoly Warned About Challenger

Roger Boisjoly was an engineer at Morton Thiokol who understood the risks of O ring failure on the Space Shuttle Challenger. For months before the January 1986 launch, he warned managers that cold temperatures could cause catastrophic failure. On the night before launch, he argued strongly for delay. His concerns were recorded and discussed. Management chose to proceed. The shuttle exploded shortly after liftoff, killing all seven astronauts aboard.

After the disaster, Boisjoly testified before investigative panels, confirming the risk had been known. He later described the emotional toll of watching preventable tragedy unfold. His warnings existed in writing and in meetings. They were not ignored by accident. They were consciously overruled under pressure to maintain schedules and appearances. Boisjoly did not benefit from speaking up. His career suffered. Today, his experience is often cited in discussions about ethical responsibility and organizational silence. Challenger remains a case study in how warnings can reach decision makers and still fail to change outcomes.

4. Diane Vaughan Identified A Dangerous Pattern

Sociologist Diane Vaughan studied NASA long before the Challenger disaster and noticed a troubling pattern. Technical anomalies were repeatedly reclassified as acceptable risks rather than treated as warnings. Vaughan documented how organizations slowly normalize problems when nothing immediately goes wrong. Her research showed that danger does not always come from sudden failure, but from gradual acceptance of deviation. Before Challenger, her work attracted little attention from decision makers.

After the explosion, Vaughan’s findings gained prominence. She explained that warnings often lose power when they appear routine. Engineers and managers become accustomed to small failures, redefining them as normal. Vaughan did not predict a single accident. She warned about a culture that made accidents inevitable. Her work shifted how organizations understand risk and accountability. It showed that warnings can exist within systems as data, reports, and analyses, yet remain ineffective without leadership willing to confront uncomfortable truths.

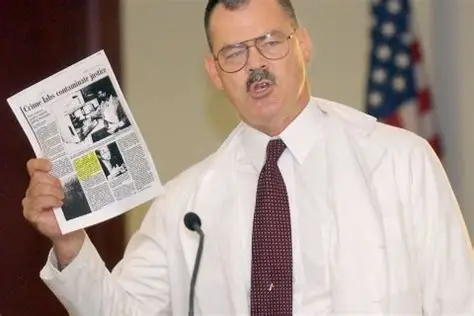

5. Fred Whitehurst Challenged FBI Forensics

Fred Whitehurst was a forensic scientist working for the FBI in the 1990s when he noticed serious flaws in the bureau’s crime lab practices. He warned that evidence handling lacked scientific rigor and that testimony often overstated certainty. Whitehurst raised concerns internally, documenting errors that could affect convictions. His warnings were met with resistance and personal backlash. Instead of fixing the problems, leadership questioned his motives and isolated him.

Years later, investigations confirmed widespread issues in the FBI crime lab. Dozens of cases were affected, and the Justice Department acknowledged systemic failures. Whitehurst’s warnings had been accurate and timely. Speaking up cost him professionally, but his persistence forced reform. His case highlights how institutions can protect reputation over accuracy. Forensic evidence carries enormous weight in court, and ignoring warnings about its misuse can undermine justice itself. Whitehurst showed that technical warnings matter deeply when real lives depend on them.

6. Clare Craig Questioned Early Pandemic Data

Clare Craig, a British diagnostic pathologist, raised early concerns during the COVID 19 pandemic about how data was being interpreted. She warned that testing methods and statistical assumptions could distort understanding of spread and risk. Her critiques focused on accuracy rather than denial. Craig published analyses questioning whether policy decisions fully reflected evidence.

Her warnings were controversial and often dismissed as disruptive. While not all her conclusions were accepted, later reviews acknowledged that data interpretation during crises is complex and prone to error. Craig’s experience shows how early warnings during emergencies face intense scrutiny. Speed can override caution. Her case reminds us that questioning data is not opposition. It is part of scientific process. When urgency dominates, even reasonable warnings can be sidelined until hindsight forces reevaluation.

7. Stanley Milgram Warned About Obedience

Psychologist Stanley Milgram conducted obedience experiments in the 1960s that revealed how ordinary people comply with authority even when causing harm. His findings warned that situational pressure could override personal ethics. Milgram argued that obedience played a major role in historical atrocities. At the time, many critics focused on the ethics of his experiment rather than its implications.

Milgram’s warning was not about a single event, but about human behavior itself. Over time, his work became central to understanding institutional abuse and moral responsibility. The discomfort his findings caused delayed their acceptance. Today, his research is cited in discussions of military conduct, corporate culture, and political power. Milgram showed that warnings about human tendencies are often hardest to accept because they implicate everyone, not just leaders.

8. Edward Snowden Raised Surveillance Concerns

Edward Snowden was a contractor for the U.S. National Security Agency when he discovered extensive government surveillance programs. He warned that mass data collection violated privacy and exceeded public consent. Snowden tried raising concerns internally before leaking documents. When he saw no response, he chose disclosure.

The reaction focused heavily on his actions rather than the warnings themselves. Over time, courts and lawmakers acknowledged that some programs exceeded legal limits. Snowden remains a polarizing figure, but his warnings reshaped global conversations about privacy and state power. His case shows how whistleblowers often become the story, eclipsing the warning they carry. Whether viewed as hero or traitor, the issues he raised continue to influence policy, proving that dismissed warnings can still change history.

9. Sherron Watkins Raised Enron Red Flags

In 2001, Sherron Watkins was a vice president at Enron when she began to notice accounting practices that did not make sense. She reviewed internal structures and realized the company was hiding massive losses through complex partnerships. Watkins wrote a detailed memo to CEO Kenneth Lay warning that Enron could collapse in a wave of accounting scandals. She urged leadership to investigate quietly before public exposure destroyed the company. Her warning stayed inside executive circles and no decisive action followed.

Within months, Enron filed for bankruptcy, wiping out jobs and pensions. Watkins later testified before Congress, explaining that the warning signs were clear long before the collapse. Her memo became public only after the damage was done. Watkins did not stop Enron, but her experience revealed how internal warnings can be acknowledged without being acted upon. The systems meant to protect organizations often fail when reputation and profit outweigh accountability.

10. Barry Jennings Questioned World Trade Center Seven

Barry Jennings was a deputy director with the New York City Housing Authority and was inside World Trade Center Seven on September 11, 2001. He reported hearing explosions inside the building hours before it collapsed later that afternoon. Jennings described being trapped by stairwells that suddenly failed. His accounts conflicted with early official explanations. Over time, his statements received limited attention.

As investigations progressed, focus shifted toward simplified conclusions that left little room for unresolved questions. Jennings continued to stand by his experience until his death in 2008. His warnings did not fit neatly into established narratives, and they were gradually sidelined. His story illustrates how eyewitness accounts can be acknowledged yet quietly minimized when they complicate official explanations. Sometimes warnings fade not because they are disproven, but because they are inconvenient to pursue further.

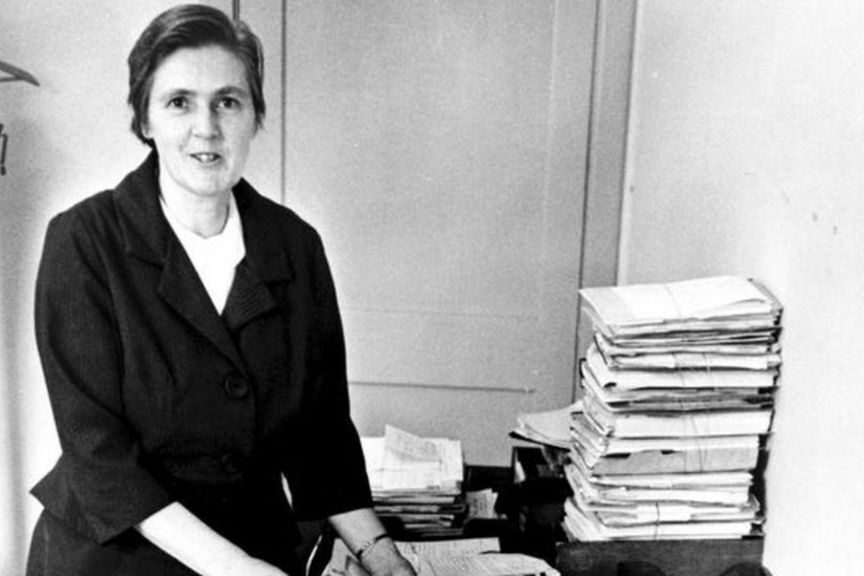

11. Frances Oldham Kelsey Stopped Thalidomide

In the early 1960s, Frances Oldham Kelsey worked as a medical officer at the United States Food and Drug Administration. Her role was to review new drug applications, including one for thalidomide, a sedative already sold in Europe. While the drug was being promoted aggressively, Kelsey noticed gaps in safety data, especially regarding use during pregnancy. She repeatedly requested additional studies instead of approving it. Her warnings were quiet and procedural, expressed through formal refusals rather than public objections. Drug manufacturers pushed back, frustrated by delays they viewed as unnecessary.

Kelsey held firm, insisting that safety evidence mattered more than speed. In countries where thalidomide was approved, thousands of babies were born with severe birth defects. In the United States, approval never came. Her decision prevented widespread tragedy before it could occur. Kelsey later received national recognition, but at the time, her caution was simply part of her job. Her story shows how warnings do not always arrive as alarms. Sometimes they appear as patient insistence on doing things correctly, even when pressure encourages shortcuts.

12. Andrew Wakefield Triggered Medical Controversy

In 1998, Andrew Wakefield published a study claiming a link between the measles vaccine and autism. The paper received immediate media attention and sparked fear among parents. Wakefield presented his claims as a warning about vaccine safety, urging caution. However, many scientists raised concerns almost immediately about the study’s design, small sample size, and conclusions. These professional warnings were initially drowned out by public anxiety and sensational coverage.

Over time, investigations uncovered serious ethical violations and data manipulation. The study was retracted, and Wakefield lost his medical license. Vaccination rates fell in several countries, leading to outbreaks of preventable diseases. This case illustrates that not every warning deserves equal trust. It also shows the danger of elevating unverified claims while ignoring qualified skepticism. Warnings require responsibility and evidence, not just attention. The harm here came not from ignoring a warning, but from failing to challenge one strongly enough before it reshaped public behavior.

13. Chelsea Manning Exposed Military Records

Chelsea Manning served as an intelligence analyst in the United States Army with access to classified military data. While deployed, Manning became troubled by reports showing civilian casualties and internal assessments that contradicted public statements. She attempted to raise concerns through internal channels, believing the information revealed serious ethical problems. When those concerns received no response, Manning decided to release the documents publicly.

The disclosures sparked international debate over transparency, security, and accountability. Attention quickly shifted toward Manning’s actions rather than the content of the warnings themselves. Some revelations later aligned with independent investigations confirming civilian harm. Manning faced severe legal consequences, while institutions focused on containment rather than reflection. Her case highlights how warnings can be lost when systems prioritize control over correction. When internal pathways fail, warnings may surface in disruptive ways that overshadow their original intent and complicate meaningful discussion.

14. Jeffrey Wigand Spoke Against Big Tobacco

Jeffrey Wigand worked as a research scientist for Brown and Williamson, one of the largest tobacco companies in the United States. He became aware that nicotine levels were being manipulated to increase addiction. Wigand raised concerns internally, warning that the company’s public statements about addiction were misleading. His objections were not welcomed, and he was eventually dismissed.

After leaving the company, Wigand spoke publicly about what he had seen. The tobacco industry responded with legal pressure and personal attacks aimed at discrediting him. Over time, investigations confirmed widespread deception within the industry. His warnings contributed to major lawsuits and regulatory reforms. Wigand’s experience shows how corporate power can suppress internal warnings until external exposure forces change. Speaking up carried heavy personal cost, but it altered public understanding of smoking risks and accountability.

15. Karen Silkwood Raised Nuclear Safety Issues

Karen Silkwood worked at the Kerr McGee nuclear facility in Oklahoma during the 1970s. She reported repeated safety violations, including improper handling of radioactive materials. Silkwood gathered documentation and raised concerns with supervisors and union representatives. She believed worker safety was being compromised to maintain production schedules.

Before she could fully present her evidence, Silkwood died in a car accident under unclear circumstances. Investigations later found radioactive contamination in her apartment. Many questions surrounding her death and warnings remain unresolved. Her case became symbolic of the risks faced by whistleblowers in hazardous industries. Silkwood’s story reminds us that some warnings disappear along with the people who carry them, leaving uncertainty where accountability should have been pursued.

16. Vasili Arkhipov Prevented Nuclear Escalation

In October 1962, during the Cuban Missile Crisis, Vasili Arkhipov served as second in command aboard the Soviet submarine B 59. The submarine had lost communication with Moscow and was surrounded by U.S. naval forces dropping depth charges as warning signals. Inside the submarine, conditions were extreme. Heat, exhaustion, and fear were mounting. The captain believed war may already have begun and prepared to launch a nuclear torpedo. According to protocol, unanimous consent from three senior officers was required. Two agreed that launch was justified. Arkhipov did not.

Arkhipov argued that there was no confirmation of war and refused to authorize the launch. His resistance stopped the weapon from being fired. At the time, his decision was not publicly known or recognized. Only decades later did historians confirm how close the world had come to nuclear catastrophe. Arkhipov did not file a report or issue a warning in words. His warning came through refusal. His story shows how restraint can matter as much as alarm. Sometimes the most powerful warning is the decision to slow down when others rush toward irreversible action.

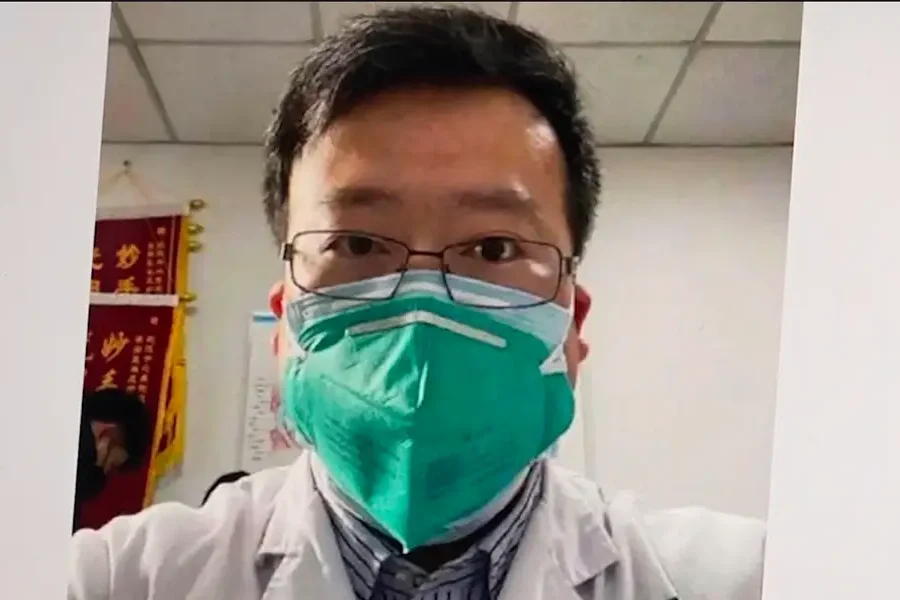

17. Li Wenliang Tried To Warn His Colleagues

In late 2019, Li Wenliang was an ophthalmologist working at a hospital in Wuhan, China. He noticed patients showing symptoms similar to SARS and shared his concerns privately with fellow doctors. His message was intended as a warning, not a public statement. Authorities accused him of spreading false information and summoned him for questioning. He was forced to sign a statement admitting wrongdoing and promising silence. His warning ended there, at least officially.

As cases increased and the virus spread globally, Li became recognized as one of the earliest voices to raise concern. He later contracted the virus while treating patients and died in February 2020. Public reaction to his death was widespread, with many acknowledging that his warning had been accurate. Li’s story reflects how early signals are often treated as disruption rather than caution. His experience quietly ties these stories together. Warnings often begin as simple observations shared among professionals. When systems suppress them, consequences expand. Listening early is not about panic. It is about allowing truth to surface before damage becomes unavoidable.