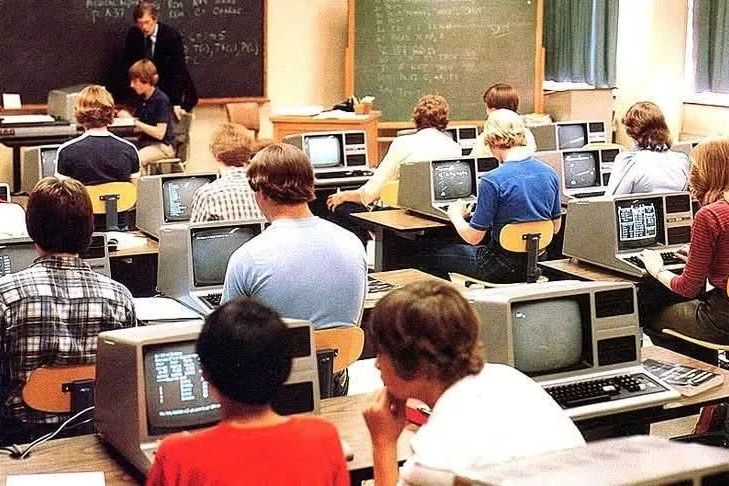

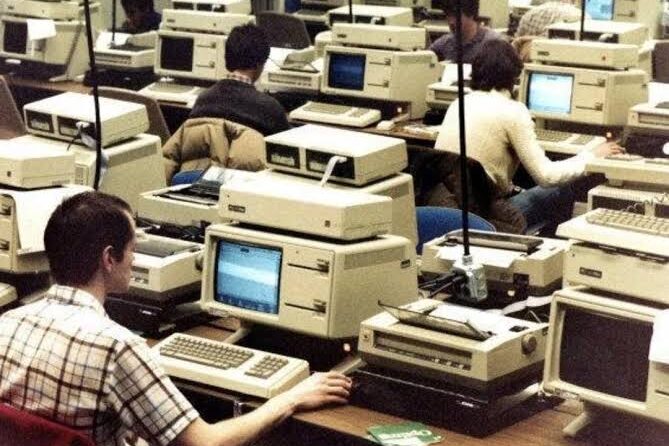

1. Computer Labs Felt Like Stepping into the Future

For many of us, the computer lab was the first true glimpse of the digital world. Walking into one was like entering a spaceship: long rows of bulky CRT monitors glowed under cool fluorescent lights, connected to beige towers that hummed with a collective mechanical sound. This was a stark contrast to the familiar environment of ink, chalkboards, and paper. The air itself felt different, electric, sterile, and filled with the possibility of creation, learning, and, most importantly, games. Teachers became guides to a mysterious new landscape where lessons were on a screen instead of a blackboard, fundamentally changing how we interacted with information and solidifying the lab’s status as a space that felt truly alien and exciting. The lab was the physical manifestation of a tomorrow that was just beginning to arrive.

2. Floppy Disks Were the Keys to the Kingdom

Before gigabytes and flash drives, floppy disks were the sole currency of digital storage, and students treated them as literal treasure. These fragile squares of plastic held everything from our homework to the most coveted programs, making them essential. We’d clutch our disks like protective talismans, ensuring they weren’t bent, smudged, or left near magnets. The entire foundation of a school project, a prized game, or even the operating system itself rested on that thin, magnetic platter. The ritual of carefully sliding the disk into the drive and hearing the click of the locking mechanism was a moment of suspense. Without the right disk, you were locked out, your work inaccessible, your progress halted, making the floppy the undisputed master key to the entire computer experience.

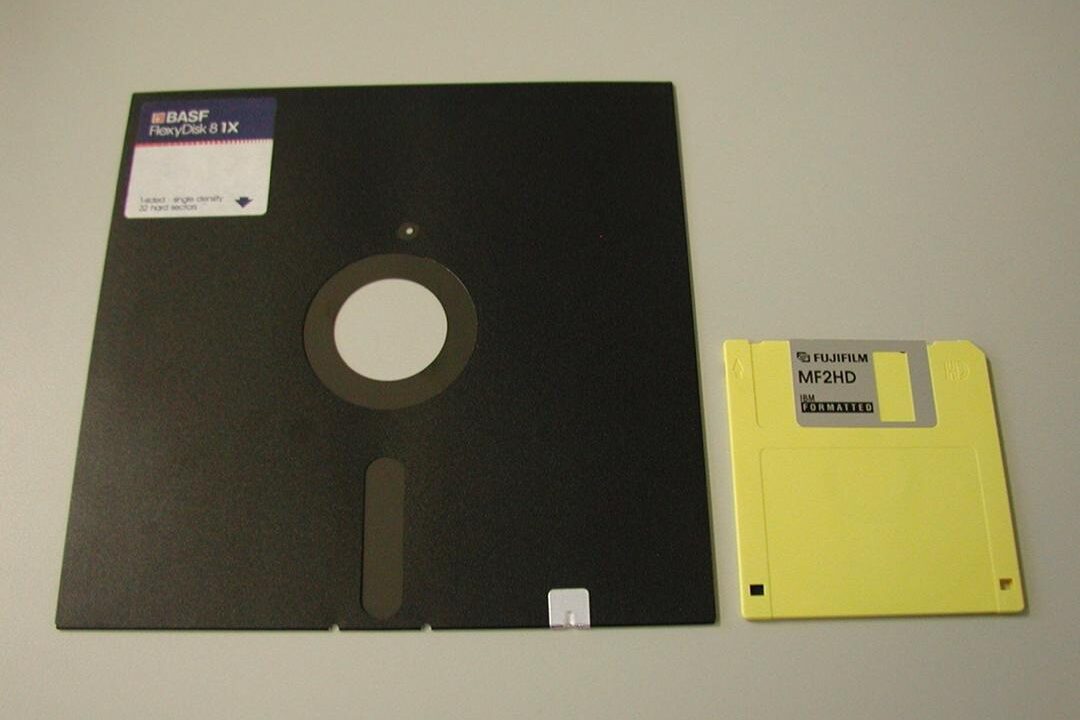

3. The Original 8-Inch Floppies Were Enormous

The very first “floppy” disks, introduced by IBM in the early 1970s, were truly massive. They measured 8 inches in diameter and were encased in a flexible, square jacket. Designed primarily to load microcode into their System/370 mainframes, these early disks were incredibly expensive and stored a minimal amount of data by today’s standards, around 80 kilobytes (KB) in their earliest forms. Their size and flimsiness were notable; they could bend easily, and the magnetic disk surface was often visible through a cutout, leading to constant warnings from technicians about touching the exposed media. They looked more like vinyl records than the storage devices we later came to know, marking the awkward, pioneering start of portable digital data.

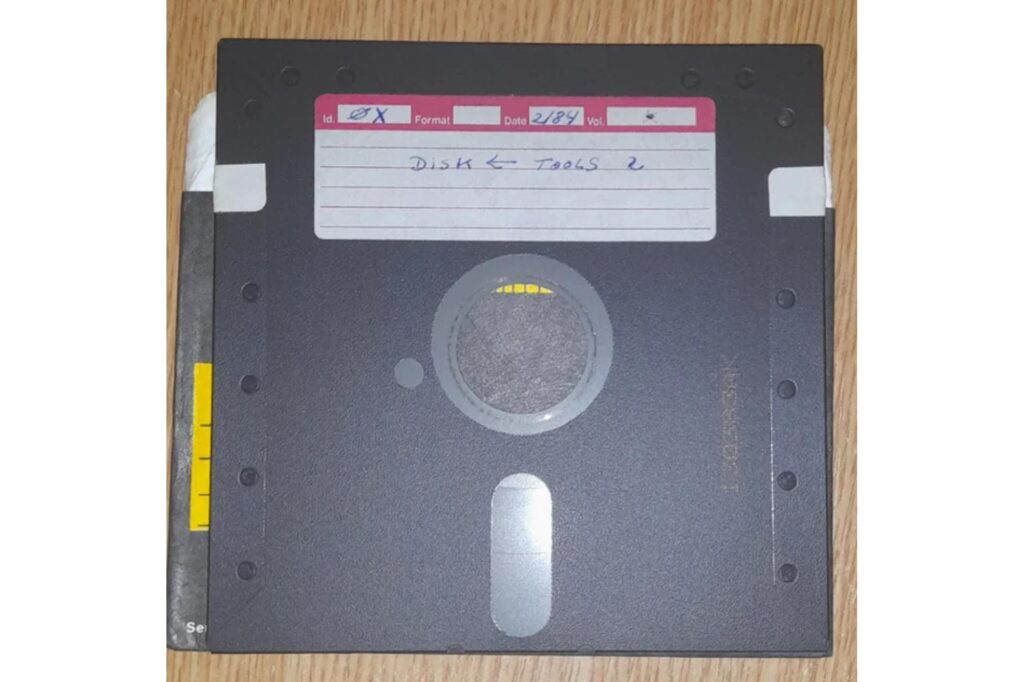

4. The 5.25-Inch Floppy Was the Classroom Standard

By the late 1970s and throughout the 1980s, the smaller, more manageable 5.25-inch floppy disk became the dominant storage medium for personal computers like the Apple II and Commodore PET. These disks were truly floppy, consisting of a thin, flexible plastic medium housed in a soft plastic or paper sleeve. They were incredibly prone to damage, a single fingerprint on the exposed read/write hole, a crease in the jacket, or a stray pencil mark could render the data unreadable. Kids often decorated their paper sleeves with stickers, doodles, and detailed labels, proudly owning the digital equivalent of a three-ring binder. The ritual of carefully sliding one out of its protective sleeve and inserting it into the drive defined a generation of early computing.

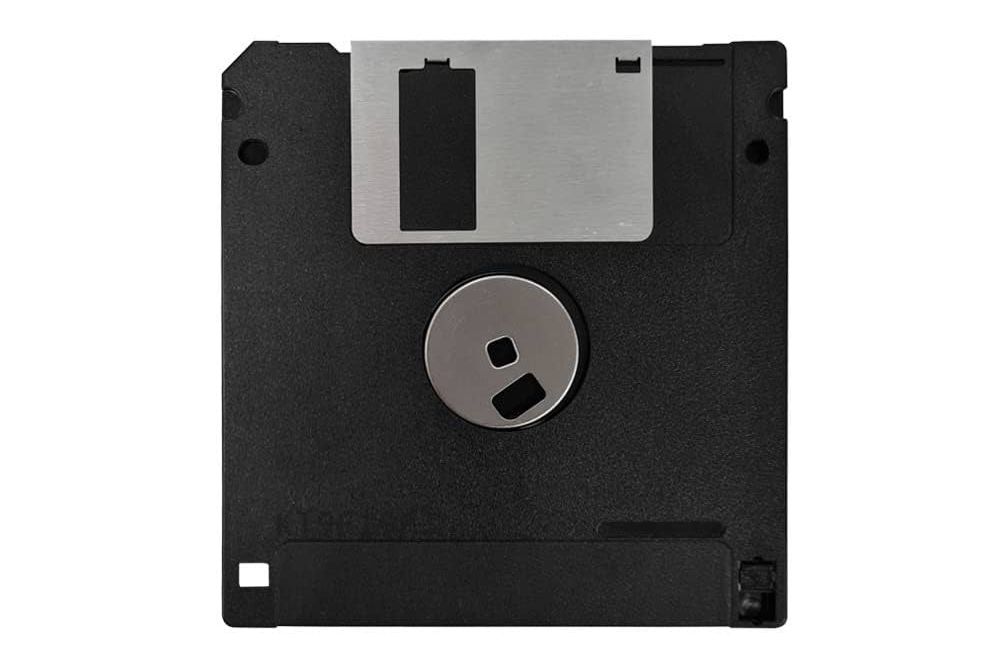

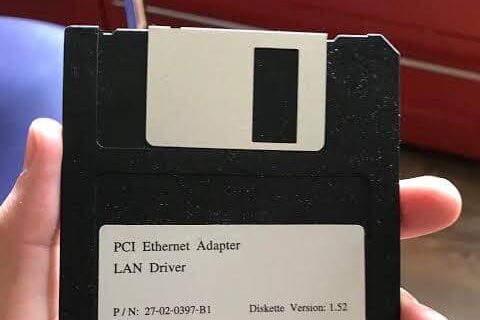

5. The 3.5-Inch Floppy Felt Indestructible

The introduction of the 3.5-inch floppy disk in the mid-1980s was a monumental step forward in data durability and portability. Unlike their larger, flexible predecessors, these disks were housed in a rigid plastic shell, giving them a sturdy, modern feel. The most innovative feature was the sliding metal shutter, which automatically protected the magnetic media when the disk wasn’t in use, shielding it from dust and fingerprints. Holding up to 1.44 megabytes (MB) of data, which was significantly more than the 5.25-inch disks, they became the icon of ’90s computing, easily fitting into shirt pockets and allowing students to carry stacks of projects and games in specialized plastic carrying cases, making data transfer finally feel reliable and easy.

6. Saving a File Meant Holding Your Breath

The process of saving a file on a floppy disk was often a suspenseful affair, especially for a critical school project. After issuing the “Save” command, the computer would often pause, and the disk drive would spring to life with a series of grinding, whirring, and clicking noises that sounded loud in the quiet lab. A student’s eyes would fixate on a blinking cursor or a slow-moving progress bar, praying the save process wouldn’t abort. The arrival of the dreaded “Disk Full,” “General Failure,” or “Write Protect Error” message was an instant moment of dread, meaning minutes or even hours of work could be lost in a flash. The simple act of saving taught a generation about the fragility of digital data and the importance of repeated backups.

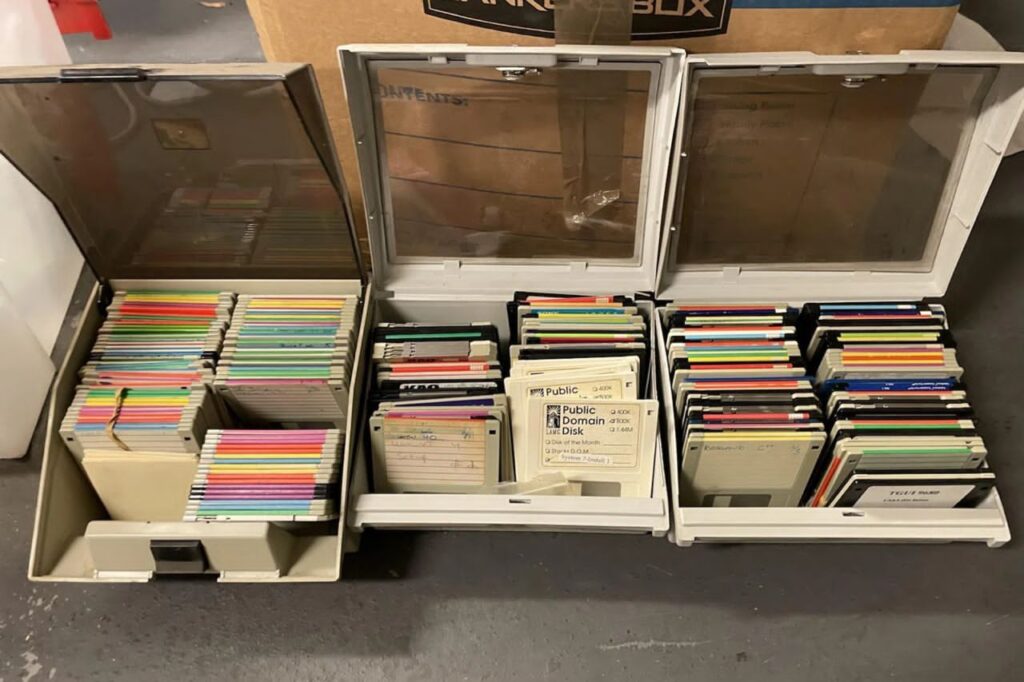

7. Every Student Had a Disk Box

Organization for the digitally conscious student centered around the floppy disk box, a plastic container designed to hold and protect a stack of 3.5-inch or 5.25-inch disks. These containers, often a clear or solid color with a snap-shut lid, were the personal archives of our digital lives. Opening one revealed a curated collection: disks labeled “Book Report,” “Math Games,” “Oregon Trail Save,” and “Typing Lessons.” While the inside was sometimes organized with dividers, it could just as easily be a chaotic jumble of mislabeled floppies. The disk box was a symbol of ownership and responsibility, a portable office that ensured a student was always prepared, or at least armed, for their next computer lab session.

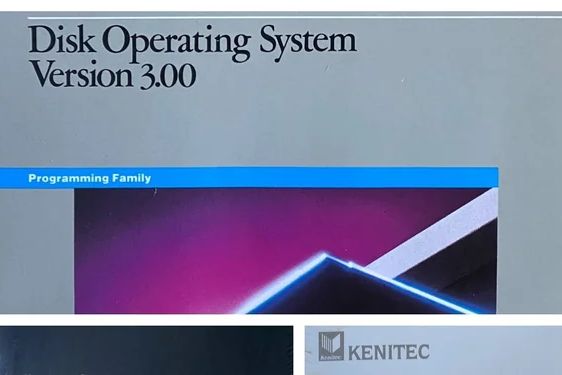

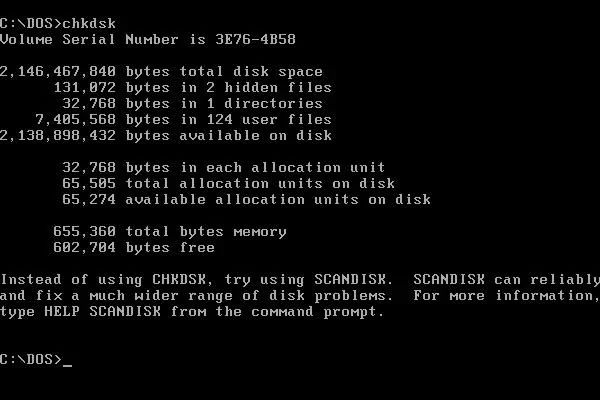

8. Boot Disks Controlled Everything

In the era of early personal computers, many machines couldn’t simply start on their own; they required a boot disk to load the operating system. This was particularly true for computers running DOS (Disk Operating System). The ritual began with the student inserting a floppy disk containing essential system files and then powering on the machine. The screen would remain black until the drive finished its heavy grinding to load the core software. Without the correct boot disk, the machine was useless, typically displaying a prompt like “Non-System disk or disk error” or simply “A>,” trapping the user in a digital limbo. Forgetting a boot disk at home meant being locked out of the machine and the class assignment, teaching a harsh lesson about preparedness.

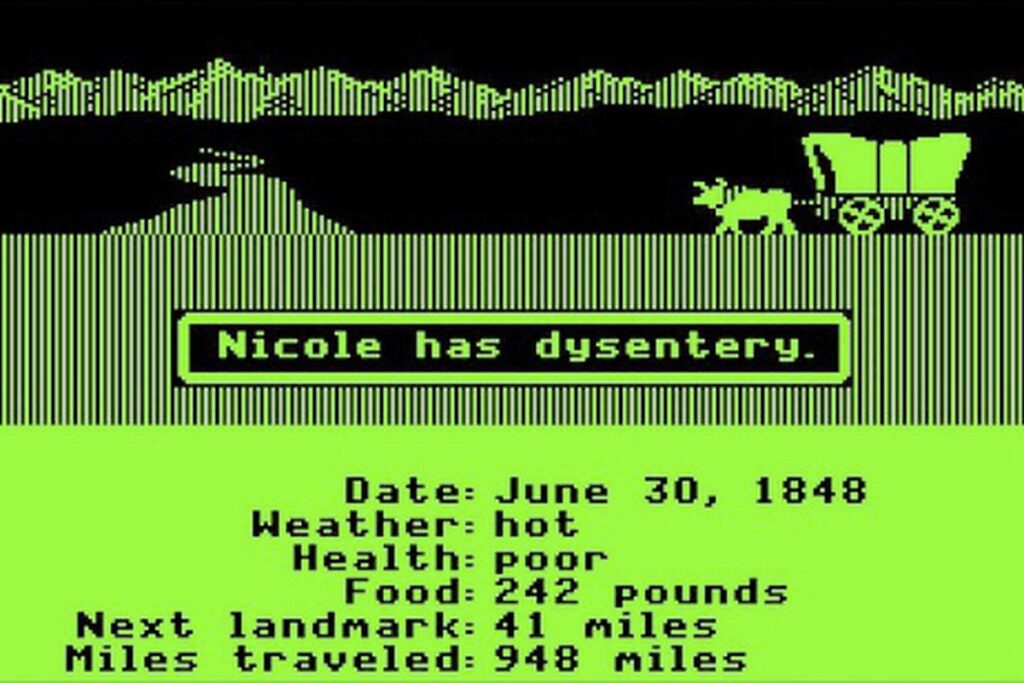

9. Oregon Trail Was the Crown Jewel of Labs

No game dominated the school computer lab landscape quite like The Oregon Trail. It was less a game and more a cultural rite of passage for students, who eagerly lined up to take turns guiding a pixelated wagon family from Missouri to the Willamette Valley. The decision-making was intense: how much to buy, when to hunt, and when to try and ford the river. Everyone knew the pain of losing oxen, losing a family member to an injury, or the inevitable, dreaded diagnosis of dysentery. Beyond the fun, the game subtly taught resource management, American history, and simple probability, making it one of the few pieces of entertainment that teachers could proudly justify as an essential part of the curriculum.

10. Carmen Sandiego Turned Kids into Detectives

The educational games featuring Carmen Sandiego transformed computer time into a thrilling geography and history lesson. Titles like Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego? armed students with floppy disks and the World Almanac, which was often the required “decoder” for certain clues. Students would pour over clues about national flags, currencies, and capital cities to track the elusive criminal mastermind and her V.I.L.E. henchmen across the globe. The game fostered a genuine love for investigative work and critical thinking, all while making dry facts about global geography exciting. Successfully catching a villain felt like a brilliant achievement, solidifying the game as a classic blend of adventure and learning.

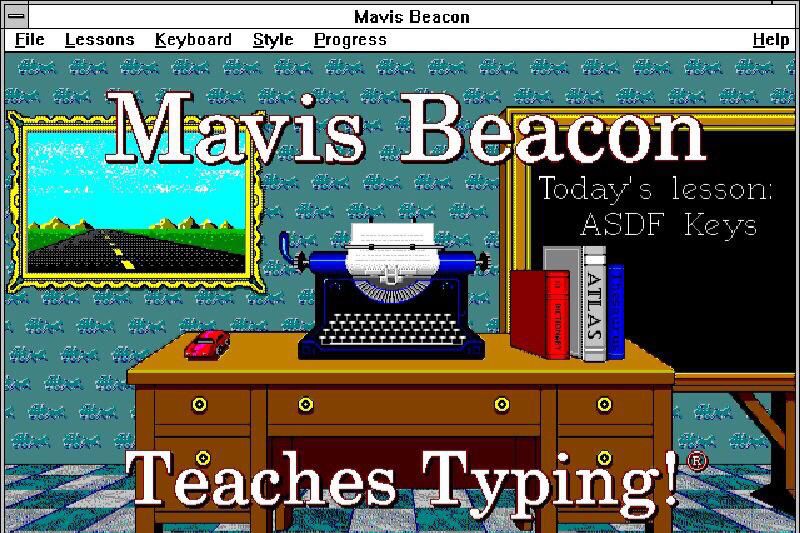

11. Typing Programs Became Daily Drills

Before touchscreens, the keyboard was the primary interface with the digital world, and typing proficiency was mandatory. Programs like Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing turned the often-dull subject into a competitive, high-stakes game. Students would perform color-coded, timed lessons, striving for accuracy and speed, with mistakes often met with funny sound effects or cartoon scoldings. The lab was filled with the rhythmic clack-clack-clack of keys, with students focused intensely on improving their words per minute (WPM) score. Typing class was the ultimate competition, where students covertly compared scores, eager to prove they had the fastest fingers in the lab, a skill that felt less like schoolwork and more like a superpower.

12. Dot-Matrix Printers Screeched in the Background

The soundtrack of the early computer lab was often dominated by the high-pitched, relentless screeching and grinding of the dot-matrix printer. These machines created images and text by striking an ink-soaked ribbon with a tight array of pins. They printed assignments line by line, on continuous, perforated fanfold paper with tear-off strips on the sides. The noise was unforgettable, a persistent, mechanical groan that signified production. After a successful print job, students would satisfyingly tear off their reports and then pull the perforated strips from the edges, turning the little strips into paper streamers or simple classroom confetti, marking the successful, tangible conclusion of a digital project.

13. Green-Screen Monitors Glowed in the Dark

Before high-resolution color displays became standard, many early computer labs were defined by the eerie, monochrome glow of CRT monitors. These screens typically displayed text and graphics in bright green or amber against a black background, a color scheme known as P-1 phosphors. The stark contrast and limited palette meant programs and games looked less like polished software and more like glowing, cryptic code. Students would sit mesmerized in the dimmed lab, staring at the intense luminescence, which often left a temporary ghost image on the screen, known as burn-in, from repeated displays. The distinctive, monochrome glow became an iconic symbol of the late 70s and 80s digital childhood.

14. Computer Time Was Carefully Rationed

Access to the limited number of computers in the lab was a prized commodity, and teachers strictly adhered to a rotation schedule. Students were often divided into small groups, and each group was granted a precious 15- to 30-minute block at a terminal. Sitting down at a functional keyboard felt like a small victory. This scarcity created a system where sharing and time management were paramount. Students learned to quickly get to work, wait patiently for their turn, and, at times, fiercely defend their limited block of time. This rationing of computer access taught patience and efficiency, but also sparked a few jealous rivalries over who got the prime time and the best machines.

15. The Sound of Drives Clicking Filled the Room

The simple act of loading a program was an acoustic experience. When a student inserted a floppy disk and typed the command to run a program, a distinct chorus of mechanical noises would erupt from the drive. There was the heavy, rhythmic grinding of the motor spinning the disk, the rapid clicking of the read/write head moving back and forth, and the final thunk as the drive found the necessary files. This loud, mechanical symphony signaled that work was being done, but also introduced a moment of anxiety. The entire lab would hold its breath until the program’s title screen finally appeared, with the collective sigh of relief when it successfully loaded being a common, unifying experience.

16. Projects Lived and Died on Disks

The fragility of the floppy disk meant that an entire semester’s worth of work could be lost in an instant. A student’s book report, an ambitious science fair essay, or early attempts at a spreadsheet all rested on the integrity of a thin magnetic layer inside a plastic square. The responsibility of maintaining the disk, keeping it away from magnets, moisture, and bending, was immense. Forgetting a critical disk at home or pulling it out of the drive prematurely could result in a catastrophic loss of data, leading to frantic explanations and, sometimes, failing grades. These disks carried the weight of entire semesters in just a few hundred kilobytes, a low-stakes lesson in data backup long before cloud storage existed.

17. Computer Teachers Became Digital Pioneers

The teachers who staffed the first computer labs were more than educators; they were the original digital pioneers for a generation. They often possessed a technical knowledge few other adults had, guiding students into a world of DOS commands, directories, and file extensions. They spoke a new language of kilobytes and baud rates, operating as the indispensable bridge between the complicated hardware and the curious students. These teachers were the early adopters who recognized the transformative power of the computer, armed with chalk in one hand and a floppy disk in the other, unlocking a complex and exciting future that many parents and administrators couldn’t yet fully grasp.

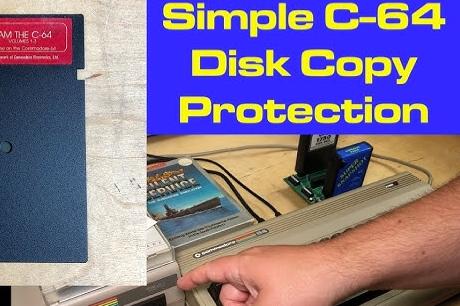

18. Copy Protection Was a Mystery to Kids

Many commercial games and sophisticated programs of the era employed elaborate copy protection schemes to prevent illegal duplication. These methods often relied on physical objects, such as a code wheel the user had to spin to match symbols on the screen, or specific words required from a page in the manual. Students would gather around terminals, whispering about rumored hacks and cheats, attempting to guess the required code after failing to input the right one. Successfully copying a disk, often through complicated, multi-step command prompts, was a moment of technical triumph that made the student feel like a genius outlaw for circumventing the system’s defenses.

19. Screensavers Became Tiny Artworks

When a computer was left idle for too long, the screensaver would come to life, protecting the monochrome monitors from “burn-in”, permanent image ghosting caused by a static display. These animated displays, from the classic flying toasters and bouncing geometric shapes to complex pixel mazes, were a source of endless fascination for students. They weren’t merely utilitarian; they were entertainment, and students sometimes wished the teacher would step away just long enough for the mesmerizing display to activate. The screensaver represented a brief, magical moment of visual relief and hypnotic, animated wonder in a world dominated by text and simple graphics.

20. Computer Carts Brought Labs into Classrooms

For schools that couldn’t afford a dedicated, fully equipped lab, the computer cart served as the portable solution. This clunky, wheeled cart, often holding a single computer, monitor, and maybe a printer, was ceremoniously wheeled into the regular classroom like a sacred, temporary artifact. The introduction of the cart meant that the single machine had to be shared among dozens of students, often rotating through one by one or in small, clustered groups. This method made lessons both chaotic and precious, as students fought for proximity to the glowing screen, but it also ensured that the crucial technology reached every student, regardless of the school’s resources.

21. Writing Papers Felt Revolutionary

Moving from handwriting to typing a paper was a significant technological and psychological shift for students. Using a word processor for the first time made the arduous process of composition feel futuristic and dramatically simplified. The ability to edit paragraphs with a keystroke, watching words shift instantly on the screen, eliminated the messy drudgery of crossing out, erasing, and rewriting. The ease of correction encouraged students to experiment with sentence structure and drafting, transforming schoolwork from a static, final product into a fluid, editable process. Typing a final, clean document felt less like manual labor and more like a high-tech invention.

22. Copying Disks Felt Like Duplication Magic

The underlying process of copying a disk, the transfer of digital information, bit for bit, from one floppy to another, often felt like an act of wizardry to the uninitiated. Students would watch the dual drives on some machines spin and whir as the contents of the source disk were cloned onto the target. The idea that entire programs, games, and large projects could be duplicated perfectly in a matter of minutes was mind-blowing. It was the first tangible experience with the power of digital replication, an early lesson in how information could be cloned and shared, seemingly defying the physical limitations of the analog world.

23. The Floppy Disk Icon Outlived the Disk Itself

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the floppy disk is its ubiquitous role as the universal icon for the “Save” function in modern software. Long after the physical disks vanished from store shelves and computer hardware, the 3.5-inch floppy image remains the default symbol. This creates a strange generational divide: those who grew up using the real disks instinctively understand the metaphor, while younger users click the icon, never realizing it represents an extinct physical object. The persistence of the icon is a quiet, powerful testament to the floppy disk’s decade-long dominance as the indispensable tool for data storage.

24. Computer Labs Were More Than Machines, They Were Doorways

Looking back, the computer lab was never just a room full of clunky, noisy hardware. It was a transitional space that defined a generation’s first touchpoint with the digital future. From the agony of a “Disk Error” to the triumph of finally killing a pixel-deer in Oregon Trail, the lab was where fundamental lessons, in typing, in logic, in patience, and in digital literacy, were absorbed. It was a shared experience of discovery, a space where the rules of the world felt different, and where every child, armed with a floppy, was granted a glimpse through the doorway into the revolutionary era of modern computing.

25. Steve Jobs Declared the Floppy Obsolete

The definitive end of the floppy disk’s reign came in 1998 with the launch of the Apple iMac G3. In a controversial and bold move, Apple eliminated the floppy disk drive entirely, choosing to focus on the newer CD-ROM and the emerging USB ports for data transfer and backups. Critics and competitors howled, asking how consumers would possibly save their files without the familiar drive. However, Steve Jobs’s decision proved prescient. It was a confident declaration that the age of slower, lower-capacity, and less reliable magnetic media was over, ushering in the era of compact discs, flash memory, and later, the cloud, marking the true dawn of modern, interconnected computing.

If you’ve ever had to furiously blow on a disk to try and fix a read error, or if the screech of a dot-matrix printer is your Pavlovian bell, you know these memories are the foundation of our digital lives. These were the lessons that taught us patience, the fragility of data, and the thrill of the digital frontier.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.

This story Insert Disk to Continue: 25 Memories of Floppy Disks & Computer Labs was first published on Daily FETCH