1. Dogs Are Domesticated Gray Wolves

It’s a tale as old as time, yet one we still find ourselves marveling at, how did the formidable, wild wolf become the furry, loyal companion curled up on our couches? Dogs are classified scientifically as Canis lupus familiaris, a subspecies of the gray wolf (Canis lupus). This close biological relationship means they share a common ancestor and can, in fact, interbreed. Genetic evidence confirms that the ancestors of all modern dogs diverged from an extinct population of gray wolves, not from any of the gray wolf lineages we see in the wild today. This divergence began tens of thousands of years ago, marking the start of a transformation that led to the staggering diversity of breeds we know today.

2. Domestication Started in the Paleolithic Era

Dogs were the first animal species ever domesticated by humans, an event that occurred long before the development of agriculture. Most estimates place the beginning of this process somewhere between 15,000 and 40,000 years ago, during the late Stone Age when humans were still hunter-gatherers. The timeline is broad and debated, but the fact remains that this partnership predates the domestication of livestock like sheep, goats, and cattle by many thousands of years, highlighting the unique value early dogs held for nomadic human groups.

3. The Self-Domestication Hypothesis is Key

The most widely supported theory is one of “self-domestication,” suggesting that the wolves themselves initiated the process by gravitating toward human settlements. Less fearful and less aggressive wolves would have been drawn to the discarded bones and food scraps around hunter-gatherer camps, gaining an advantage in survival. Over many generations, the wolves most tolerant of humans were the ones that survived and reproduced, gradually selecting for tameness without a conscious, early effort from humans to breed them.

4. Genetic Evidence Points to an Extinct Wolf Lineage

Modern genetic studies have concluded that all present-day dogs descended from a single, now-extinct population of wolves. Critically, this ancestor is genetically distinct from any modern wild wolf populations, meaning your pet is not descended from the current gray wolves in North America or Europe. Instead, a shared ancient lineage split off, and the domesticated dogs evolved along their own unique path, a revelation that has helped narrow down the timeframe and process of domestication.

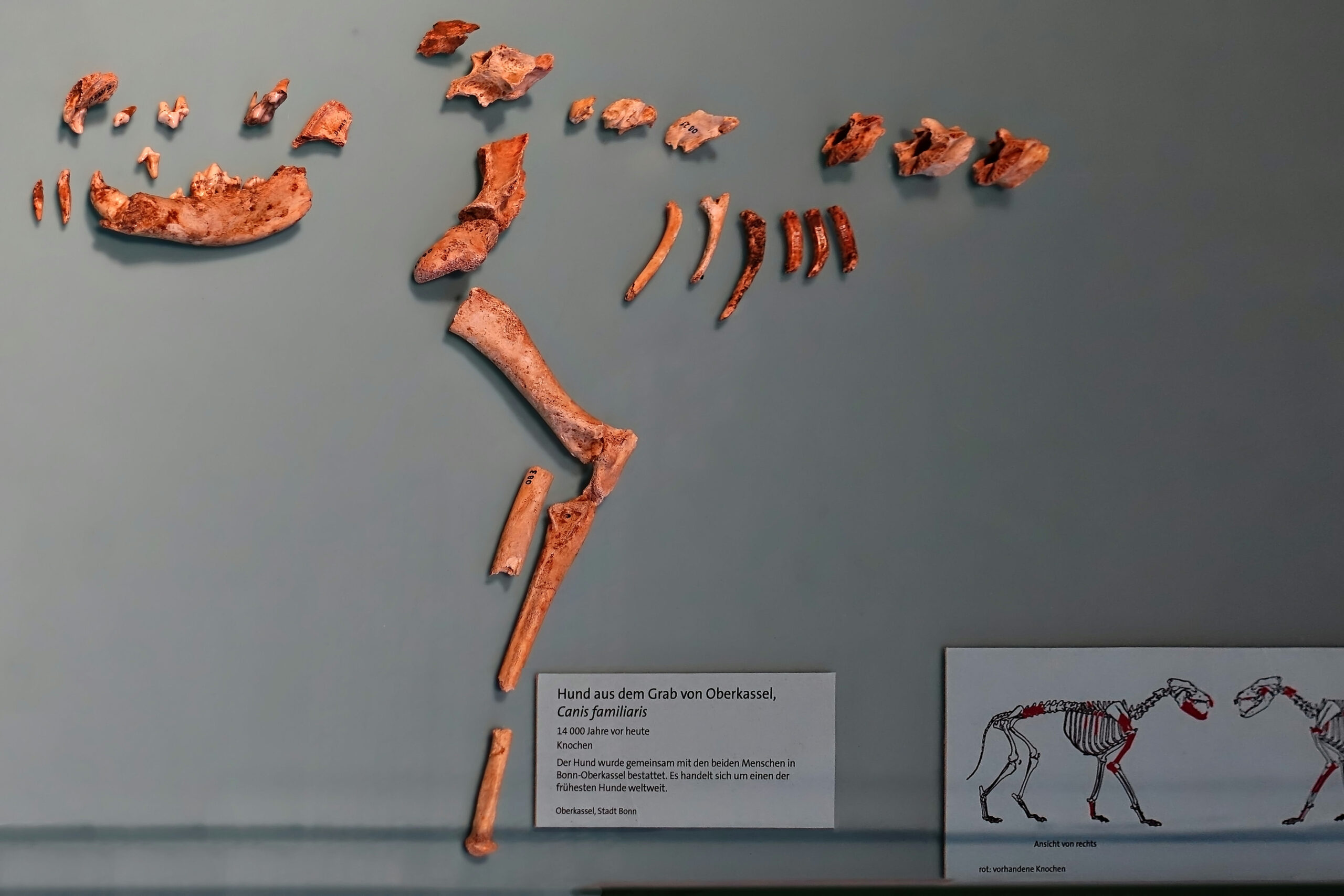

5. The Earliest Dog Remains are Debated

While the genetic timeline goes back as far as 40,000 years, the earliest universally accepted physical evidence of a domesticated dog is a specimen from Bonn-Oberkassel, Germany, dated to about 14,200 years ago. This dog was interred alongside two humans and other grave goods, suggesting a deeply significant and established relationship. However, older remains, such as those from Goyet Cave in Belgium, dating to about 33,000 years ago, are morphologically similar to dogs, though their full status as domesticated versus an ancient wolf type is still a topic of active scientific discussion.

6. Domestication May Have Occurred in Multiple Locations

For many years, scientists debated a single origin point for dog domestication, with Central Asia or East Asia often proposed. However, the most recent and comprehensive genetic studies suggest a more complex picture, indicating that wolves may have been domesticated in at least two separate geographic locations, one in Asia and one in Europe/West Eurasia. This theory proposes that these independently domesticated dog populations later interbred, explaining the complex genetic structure found in modern dogs. This dual-origin model is still being refined but suggests a widespread, parallel willingness in certain wolf populations to approach human groups.

7. The Key Trait Selected Was Tameness, Not Function

Early domestication was less about shaping a wolf for a specific job, such as herding or guarding, and more about selecting for a lower fear response and reduced aggression toward humans. Wolves that could tolerate human proximity had a survival advantage by scavenging, leading to a genetic shift toward tameness. This initial selection for behavioral traits, being less skittish and more docile, laid the essential groundwork for later, more intentional breeding efforts that focused on developing specific working roles.

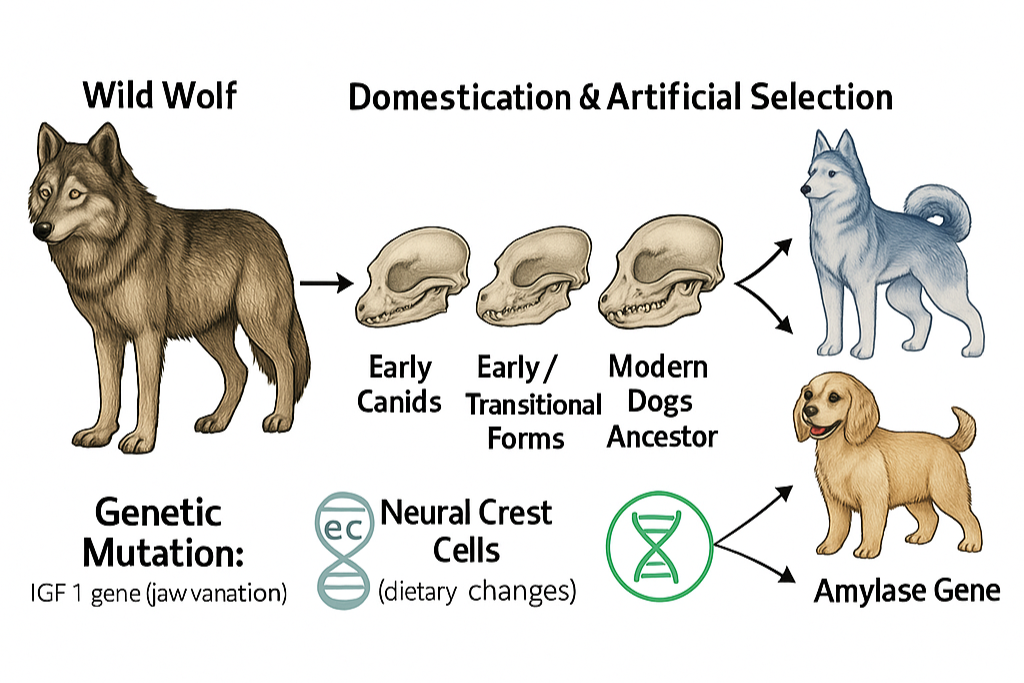

8. Physical Changes Came with Behavioral Changes

The shift from wolf to dog brought about significant physical transformations, collectively known as the “domestication syndrome.” As tameness was selected, correlated traits began to appear, including smaller overall body size, less robust skulls, and reduced tooth size compared to wolves. Another common sign is the appearance of white patches on the coat, known as piebaldism, and changes in ear carriage, often resulting in floppy ears. These physical characteristics are seen across many domesticated species and are thought to be side effects of the selection for reduced levels of stress hormones.

9. Wolves Benefited From an Easier Food Source

The initial draw for the ancestral wolves was a consistent and reliable food source. Following human hunters meant access to the discarded remains of large game animals that wolves might not have been able to take down themselves, especially during times of scarcity. This proximity to human camps provided a massive ecological niche, a safe, relatively stable supply of high-quality protein. This dependable sustenance allowed the first proto-dogs to expend less energy hunting and to focus more on survival and reproduction, driving the partnership forward.

10. Humans Gained Loyal Guards and Early Alarms

The benefits of the partnership were mutual and provided early humans with significant advantages. Wolves that were drawn to the camps quickly became de facto guards. Their keen senses of smell and hearing made them excellent early warning systems against rival human groups or large predators, providing an alert that was far superior to human senses. While early dogs may not have been actively hunting alongside humans at first, their presence contributed to the safety and security of the nomadic groups, making them invaluable members of the community.

11. Early Dogs Spread Rapidly with Humans

As the partnership solidified, the domesticated canines began traveling wherever human hunter-gatherers migrated. Genetic analysis of ancient dog remains shows that dogs followed human dispersal routes out of their regions of origin, quickly establishing populations across Asia, Europe, and eventually the Americas. This wide and relatively rapid geographic spread indicates how essential and integrated the dogs became to the success of human populations. For example, dogs arrived in the Americas with the first human settlers crossing the Bering Strait, demonstrating their already vital role in the nomadic lifestyle.

12. Dogs Helped Improve Hunting Success

The development of the dog’s working relationship with humans dramatically improved hunting efficiency. Wolves are effective pack hunters, and this cooperative ability transferred to the human-dog team. Dogs’ superior sense of smell could track prey over long distances, corner smaller game, and help locate wounded animals that might otherwise have been lost. This increased success rate in securing protein was a significant evolutionary advantage for human groups, solidifying the dog’s place as a valuable hunting partner, rather than just a scavenger.

13. Changes in Diet Influenced Dog Evolution

As dogs became more integrated into human life, their diet began to shift, a change reflected in their genetics. Wolves are pure carnivores, but early human diets, especially in settlements where starches were gathered or later cultivated, meant dogs were exposed to more plant matter. Dogs evolved to possess extra copies of the gene AMY2B, which produces pancreatic amylase, an enzyme necessary for digesting starch. This genetic adaptation marked a key divergence from the wolf, allowing dogs to thrive on a more omnivorous diet similar to their human companions.

14. The Gray Wolf’s Skull Shape is More Robust

A key physical difference between wolves and dogs lies in the structure of the skull and jaw muscles. Wolves typically have a longer, narrower snout and much more powerful jaw muscles, which are necessary for securing and killing large, struggling prey. Dogs, especially those selected for less physically demanding tasks, developed shorter, broader snouts, less pronounced sagittal crests (the ridge of bone on top of the skull), and generally weaker biting power. These physical changes are part of the domestication syndrome, often correlated with reduced aggression and reliance on hunting for survival.

15. Wolves Show Complex Social Hierarchy

Wolves live in highly structured packs with a clear hierarchy, often mistakenly described as an “alpha” structure. In fact, a wolf pack is typically a family unit led by the breeding pair. This inherent social structure, involving cooperative hunting, communication, and clear roles, made them pre-adapted to integrate into a human social structure. Early humans likely recognized and leveraged this existing complex social intelligence, finding it easier to communicate and cooperate with wolves than with other wild animals.

16. Dogs Developed Unique Communication Signals

Over generations of cohabitation, dogs developed unique ways of communicating with humans that are not seen in wolves. One of the most famous examples is their ability to read and follow human pointing gestures, a complex social cue that wolves generally do not understand. Dogs are also highly attuned to human faces and emotional expressions. This enhanced capacity for interspecies communication is a direct result of selection pressure for successful interaction with humans, facilitating cooperation and trust.

17. Intentional Breeding Started Later

While the initial process was self-domestication, humans eventually began to intentionally breed dogs for specific tasks. As human societies diversified, some relying on herding, others on agriculture, and still others on guarding property, dogs were selected for traits that enhanced these roles. This intentional selection, which began thousands of years after the initial domestication event, led to the development of the wide variety of breeds we see today, from the swift sight-hound to the powerful mastiff.

18. Dogs Became Culturally Significant and Ritualistic

The bond between dogs and humans transcended utility; dogs often held significant cultural and even spiritual importance. Archaeological evidence, such as the previously mentioned burial site in Germany, shows dogs being interred with humans, indicating respect and affection. In various ancient cultures, dogs appeared in art, mythology, and religious practices, often symbolizing loyalty, protection, or guides to the afterlife. Their ritualistic inclusion confirms their deep integration into the social and emotional fabric of early human life.

19. They Can Form Deep, Unique Bonds

The dog-human relationship is fundamentally built on an ability to form deep, lasting emotional bonds. Studies have shown that when humans and dogs interact affectionately, both experience a surge in oxytocin, often called the “love hormone,” a process mirrored in parent-infant bonding. This unique neurochemical feedback loop suggests an evolutionarily reinforced, mutual attachment that goes beyond mere cooperation for survival, explaining the enduring loyalty and companionship we still experience today.

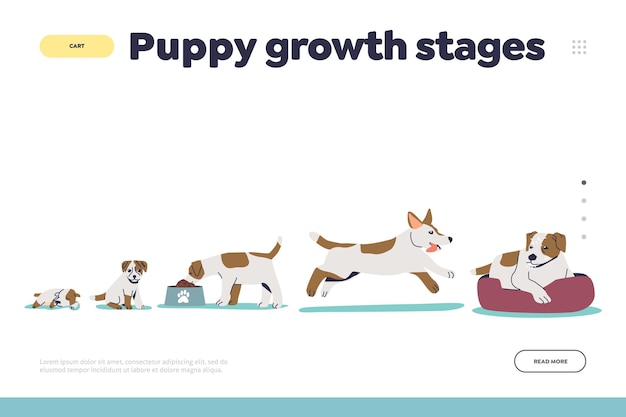

20. The “Critical Period” for Socialization is Key

Like wolves, dogs have a “critical period” during their early puppyhood, generally between 3 and 16 weeks, when they must be exposed to different stimuli, environments, and other living things to develop into well-adjusted adults. For domesticated dogs, this period is vital for learning to accept and trust humans. Wolves that were most successful at integrating into human camps likely had a slightly extended or different critical period, allowing them to form social attachments to people instead of exclusively to their wolf kin.

22. Dogs Helped Humans on the Move

For nomadic human groups, dogs proved invaluable not just for hunting but for their physical capacity to assist in carrying burdens. Though less common than in later domesticated animals, early dogs could be harnessed to pull small sledges or carry small loads strapped to their backs. Their endurance and willingness to follow over long distances made them crucial assets for highly mobile groups, helping to reduce the burden on human travelers during migration.

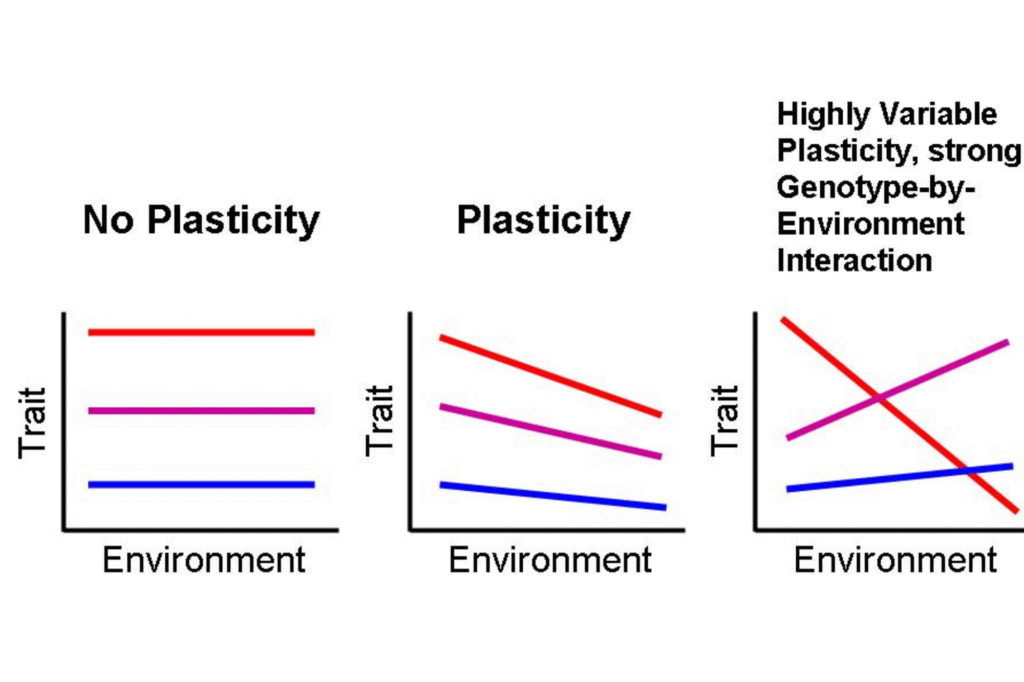

23. Early Dogs Showed High Phenotypic Plasticity

One reason dogs were such successful domesticates is their high phenotypic plasticity, meaning their genes allowed for a wide variety of observable traits (phenotypes) to emerge quickly under selective pressure. This innate flexibility meant that once humans began selecting for traits like short legs, thick coats, or specific temperaments, those traits could be rapidly exaggerated and fixed into distinct types, paving the way for the incredible morphological diversity found in modern dog breeds.

24. They Occupied a Less Competitive Niche

By associating with humans, the ancestral dogs moved into a unique ecological niche with less direct competition. While wild wolves faced competition from other predators and other wolf packs, the proto-dogs living around human camps primarily scavenged and provided services like guarding. This niche offered a safer environment and more reliable sustenance, dramatically improving their survival rate and allowing them to out-compete their wild counterparts.

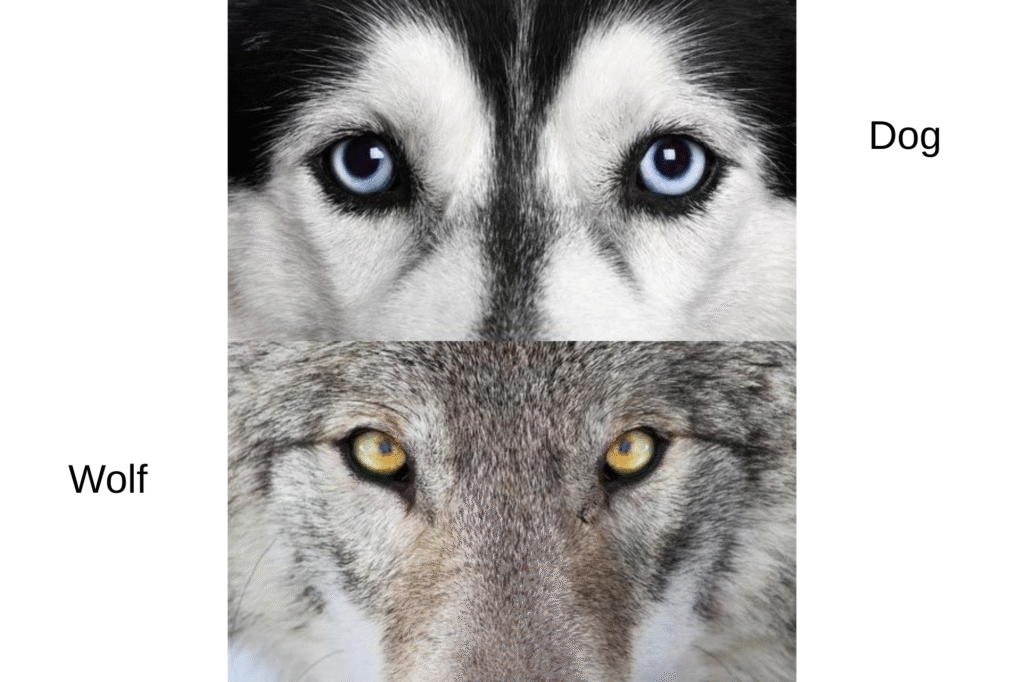

25. Wolves’ Facial Muscles Differ from Dogs

Recent research has shown that dogs have evolved specific facial muscles around the eyes that allow them to make the expressive, “puppy-dog eyes” look. Specifically, they possess a muscle called the levator anguli oculi medialis that pulls the inner eyebrow up, an action that is rarely seen in wolves. This unique anatomical difference is thought to be an evolutionary advantage selected for by humans because this particular facial expression resembles an infantile human expression, eliciting a nurturing response from people.

26. The Fear of the Unfamiliar Decreased

A significant behavioral hurdle that was overcome during domestication was the reduction in neophobia, or the fear of new things. Wild wolves are naturally cautious and fearful of anything unfamiliar. The wolves that successfully became proto-dogs had lower levels of neophobia, making them more exploratory and willing to approach the strange noises, sights, and smells of a human camp. This lowered threshold for fear was crucial for fostering the initial trust between the two species.

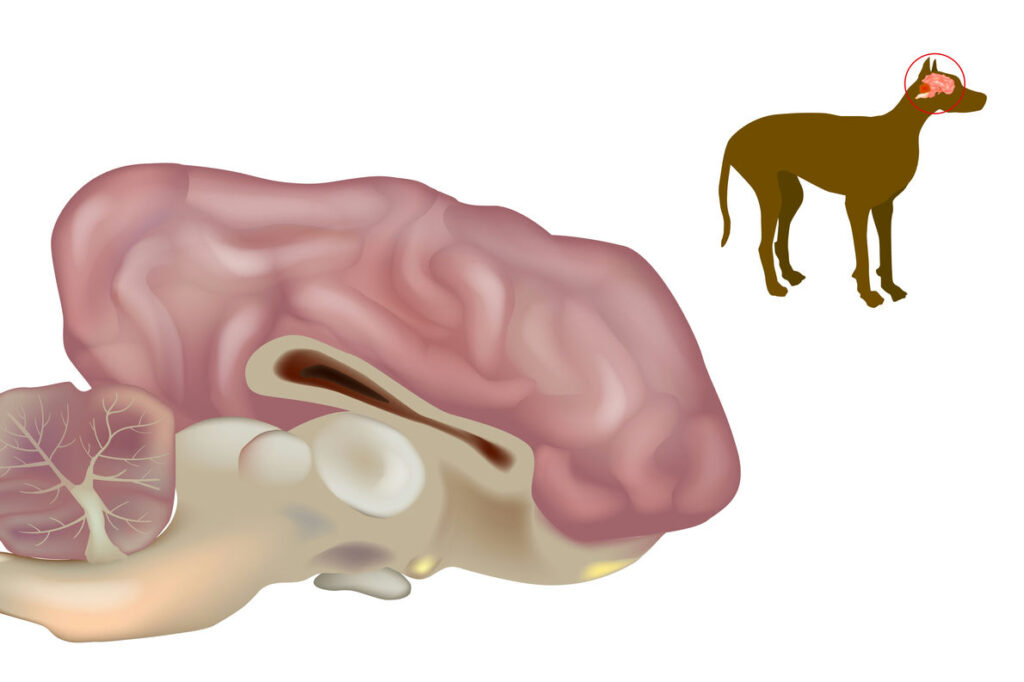

27. The Brain Structure Underwent Changes

The domestication process also led to subtle but measurable changes in the dogs’ brains compared to wolves. Dogs have smaller overall brain volumes relative to their body size than wolves. This reduction is primarily linked to the parts of the brain related to sensory processing and fighting, suggesting that domestication provided a buffer against the intense survival pressures of the wild. Having less need to be constantly alert for danger or to violently secure a kill, these brain regions could afford to be smaller.

28. Dogs’ Lifespan and Growth Rate Altered

A common characteristic of domesticated species is an altered life cycle. Dogs, compared to wolves, typically have a faster growth rate and reach reproductive maturity earlier. While their overall maximum lifespan may be comparable, dogs have been bred to enter adulthood faster. This shift in life history strategy is likely a result of living in a more protected, resourced environment provided by humans, where early reproduction is less risky than in the wild.

29. The Role of Dogs Evolved into Emotional Support

While initially valued for practical, survival-related tasks, the role of dogs in human life has evolved significantly. From the Paleolithic guard dog to the modern therapy animal, their primary function today in many societies is that of emotional support and companionship. This role highlights the depth of the mutual bond and our innate need for interspecies attachment, a need that has been cultivated over tens of thousands of years.

30. The Wolf-Dog Continuum is Still Observable

Despite the vast differences between a chihuahua (or any other dog) and a timber wolf, the evolutionary history remains clear. In the wild, instances of wolf-dog hybridization occur, though rarely. Furthermore, landrace dogs, those naturally selected in traditional human societies without strict, modern breeding standards, often retain more primitive traits, resembling their wolf ancestors more closely than specialized modern breeds, serving as a living link along the ancient continuum.

The partnership began not with a command, but with a simple willingness to approach, proving that even the most formidable wild spirit can find its greatest success and happiness right beside us.

This story How Wolves Slowly Became the First Dogs was first published on Daily FETCH