Alabama

In Alabama, roadkill salvage is legal for non-protected species or game in season no permits or reporting, just grab it and go. Rural highways like U.S. 231, snaking through pine forests south of Montgomery, teem with deer, rabbits, and armadillos, a scavenger’s jackpot for those quick on the draw. If it’s fresh still warm, eyes bright it’s yours, a no-nonsense rule that fits Alabama’s practical ethos where wasting meat is a sin against thrift and Southern roots. A driver near Mobile might spot a dusk-hit buck, toss it in the truck bed, and butcher it under a humid sky, turning a road casualty into supper with zero fuss, a testament to the state’s self-reliant spirit forged in cotton fields and backwoods.

Why do Alabamians eat it? A deer’s 50-70 pounds saves hundreds as beef climbs past $12 a pound, a lifeline for rural families in counties like Baldwin, where cash runs tight. It’s wild, cage-free, and ethical, trumping factory-farmed fare with a gamey kick that shines in stews or jerky, a taste of Dixie beating bland store cuts. It cuts roadside rot, keeping highways clean, while channeling pioneer grit, think granddaddy dressing game in lean times. The “yuck” factor scraping possum off asphalt or wrestling a busted gut churns stomachs, but for those with a blade and backbone, it’s a thrifty, flavorful haul that keeps Alabama’s resilient heart pumping in the Deep South.

Alaska

Alaska’s roadkill salvage system is as big as the state itself. With up to 1,000 moose killed annually in vehicle collisions, the program ensures that no animal goes to waste. Since the 1970s, Alaska has turned these highway tragedies into an organized effort to feed families in need. State troopers maintain a “roadkill list” of charities and individuals who are notified when a moose is struck. Volunteers arrive equipped with flatbed trucks and winches to haul away the massive carcasses, sometimes weighing over 1,600 pounds, before scavengers like bears or wolves show up. The salvaged meat is then butchered and distributed to food banks and soup kitchens.

Processing a moose is not for the faint-hearted. Tire marks on fur, ruptured organs spilling goo everywhere, and slippery conditions during icy winters are all part of the job. Salvagers must act quickly, often within 30 minutes of notification, to ensure the meat doesn’t spoil or attract predators. While Alaska’s system is efficient, it’s not without quirks: stolen roadkill occasionally makes headlines, and remote areas face logistical challenges that leave carcasses frozen solid or baking in the sun.

Arizona

Arizona’s desert highways are hotspots for wildlife collisions, especially during migration seasons when deer and elk cross sun-scorched roads in search of water. Roadkill salvage is legal here with a permit from Arizona Game and Fish, but timing is everything the desert heat accelerates decomposition within hours. Salvagers must inspect their find carefully for freshness indicators like clear eyes and warm flesh before claiming their prize. If approved, they can haul their dusty dinner home.

The why behind Arizona’s roadkill practice is simple: it’s economical and ethical. A single deer can yield up to 70 pounds of lean meat, a huge savings for families facing rising grocery costs. Many residents view it as an alternative to factory-farmed meat, offering free-range protein without the use of antibiotics or hormones. But salvaging isn’t glamorous, imagine butchering a carcass in triple-digit temperatures while dodging flies.

Arkansas

Arkansas keeps it straightforward: if it’s not protected and it’s fresh, it’s yours, no permits required! With over 22,000 deer-vehicle collisions annually, Arkansas highways offer plenty of opportunities for resourceful residents to claim free-range meat. But salvagers have to act fast; Arkansas’ humid climate means decomposition sets in quickly during warmer months. Clear eyes and firm flesh are good signs that the meat is still edible; bloating or maggots signal you’re too late.

For Arkansans willing to roll up their sleeves, salvaging roadkill is both practical and thrifty. A single deer can provide enough venison for weeks of meals, whether turned into chili or smoked jerky. But it’s not all smooth sailing. For Arkansans willing to get hands-on, salvaging roadkill can be both practical and cost-effective. A single deer can provide enough venison for weeks of meals, whether prepared as chili or transformed into smoked jerky. However, the process isn’t always straightforward; handling a carcass often involves dealing with shattered bones and bloodshot meat from impact wounds. While some people may be put off by the mess, others see it as a chance to reduce waste and make use of what nature provides.ng; processing a carcass often involves dealing with shattered bones and bloodshot meat from impact wounds. While some might shy away from the mess, others see it as an opportunity to reduce waste while making use of what nature provides.

California

California brought tech-savvy efficiency to roadkill salvage with its Wildlife Traffic Safety Act of 2020. Residents can legally claim deer, elk, pronghorn antelope, or wild pigs killed on designated roads, but only after reporting the incident through an app developed by California Fish and Wildlife. The app allows users to upload details about their find and receive instant approval to collect the carcass (assuming it hasn’t been baking too long under the California sun). Officials must euthanize injured animals before salvage is allowed.

California’s diverse geography adds complexity to roadkill salvage efforts. Cooler mountain regions like Tahoe preserve carcasses longer than desert highways near Palm Springs, where decomposition happens fast. Salvagers need sharp eyes and strong stomachs to assess freshness before hauling their find home for processing into venison chili or wild pig sausage. For

Colorado

Colorado has streamlined its roadkill salvage process with permits issued by Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW). Big-game animals like deer and elk are frequently struck on highways cutting through mountainous migration routes. If you act fast enough after spotting one with clear eyes and firm flesh, you can legally claim your next meal within 48 hours of reporting the incident online or to CPW officials.

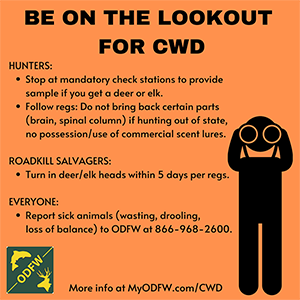

But don’t let Colorado’s cold winters fool you into thinking salvaging is easy; the icy roads make handling massive carcasses treacherous at best. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) poses another challenge; heads from salvaged animals often need testing before consumption is deemed safe. Despite these hurdles and occasional roadside gore, many Coloradans embrace roadkill as an ethical way to access free-range protein while reducing waste on highways.

Deleware

Delaware’s roadkill salvage rules are straightforward but come with a twist. If you accidentally hit a deer on a public highway, you can keep it, no questions asked, as long as you show visible evidence of the collision to state police or a Fish and Wildlife agent. Whether it’s hunting season or not, the law allows drivers to claim their venison bounty free and clear. However, if the driver doesn’t want the deer, it must be donated to a public or charitable institution, ensuring no meat goes to waste.

While Delaware’s compact size means fewer large-scale wildlife collisions compared to sprawling states, its suburban roads see plenty of deer accidents. Salvagers must act quickly in the humid climate to prevent spoilage; bloating or maggots signal it’s too late. For those willing to embrace the mess, including shattered bones and tire-tread bruises, roadkill offers a practical way to access free-range meat while reducing waste. It’s not glamorous, but for some Delawareans, salvaging deer is an unexpected win after an unfortunate fender bender.

Florida

Florida’s roadkill salvage laws are lenient, allowing residents to claim most non-protected species like raccoons, opossums, and squirrels without permits. However, for larger animals like alligators or species classified as threatened or endangered, a special permit from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) is required. Taxidermists can legally mount salvaged carcasses of certain species, provided they maintain proper documentation and tags. With its subtropical environment and abundant wildlife, Florida sees frequent collisions involving deer, armadillos, and even alligators. These accidents create an opportunity for resourceful Floridians to salvage fresh meat, if they act quickly.

The science behind roadkill salvage in Florida is all about timing. Decomposition happens rapidly in the state’s humid climate, meaning salvagers must inspect carcasses for clear eyes and firm flesh to ensure freshness. Burst organs or discoloration signal spoiled meat that’s unsafe to consume. While salvaging isn’t for the squeamish, bloodshot meat and tire marks are common; it’s a practical way to reduce waste while providing free protein. Some Floridians turn their finds into creative dishes like gator gumbo or venison stew, proving that even roadside accidents can yield culinary surprises.

Georgia

Georgia’s roadkill salvage laws are as southern as sweet tea, practical, straightforward, and tinged with a bit of charm. If you hit a deer, you can keep it without much fuss, but if the unfortunate victim is a black bear, you’ll need to notify the authorities. The state’s warm climate doesn’t give salvagers much time to act; decomposition sets in fast, especially during muggy summers. Georgia’s rural roads are hotspots for wildlife collisions, particularly during mating seasons when deer are more active near highways.

But here’s where Georgia adds its unique twist: roadkill has been whispered about as an ingredient in southern classics like Brunswick stew, a hearty mix of meat and veggies that may (allegedly) include squirrel or rabbit. While not officially confirmed, the idea of turning roadside critters into comfort food is part of Georgia’s resourceful spirit.

Idaho

Idaho’s roadkill salvage law, enacted in 2012, has become a surprising success story. Since its inception, over 4,800 animals, including nearly 2,000 whitetail deer, 1,405 mule deer, 798 elk, and 308 moose, have been salvaged from Idaho’s highways. Residents can legally claim wildlife killed in vehicle collisions by reporting the incident to Idaho Fish and Game within 24 hours and obtaining a free salvage permit within 72 hours. The process is straightforward: fill out an online form or contact the department to obtain your permit. Salvagers can take as much or as little of the animal as they wish, whether it’s the backstraps for dinner or antlers for display.

The law isn’t just about reducing waste; it’s also helping biologists track collision hotspots and develop solutions like wildlife underpasses and moose alert signs on highways. While salvaging isn’t glamorous, burst organs and tire-tread bruises are common, Idahoans see it as a practical way to turn accidents into opportunity. However, safety is key: pulling over on busy roads to retrieve carcasses can be risky, and salvagers must ensure the meat is safe from contamination or diseases like Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD).

Illinois

Illinois takes roadkill salvage seriously, with laws that allow residents to claim deer and other animals killed in vehicle collisions. The state’s “Roadkill Bill” permits anyone with a valid hunting or trapping license, or a habitat stamp, to legally collect carcasses for food or pelts. Drivers involved in collisions have priority to claim the animal, but if they pass, any Illinois resident can step in, provided they’re not delinquent on child support. Yes, that’s an actual rule. Salvagers must report their find within 24 hours using the Department of Natural Resources’ online form, detailing everything from the deer’s sex to its antler points.

Roadkill isn’t just about venison steaks in Illinois; raccoons and muskrats are also popular among furriers, with pelts generating $1.2 million in sales as recently as 2010. However, salvagers need to act quickly; decomposition sets in fast during the state’s humid summers. Gloves and protective gear are recommended for handling carcasses, and the meat must be cooked to at least 160°F to kill bacteria. Whether it’s turned into chili or mounted as a taxidermy project, Illinois residents see roadkill as both a practical resource and a quirky part of their outdoorsy culture.

Indiana

Indiana’s roadkill salvage system is all about permits and precision. Residents can legally claim deer, squirrels, rabbits, and even otters, but only with a special purpose salvage permit issued by the Department of Natural Resources (DNR). The process requires applicants to specify their reason for salvaging, whether it’s for food, education, or scientific study, and tag the animal with details like the date and county of collection. The law prohibits using salvaged animals for commercial purposes, so you can not turn your roadside find into jerky for sale.

Salvaging in Indiana isn’t just about filling freezers; it’s also a tool for conservation. Data collected from permits helps track wildlife collisions across the state’s highways, informing efforts to reduce accidents. However, timing is everything. Indiana’s humid summers mean decomposition sets in quickly, making freshness checks essential. For those willing to brave tire marks and gooey guts, roadkill offers both practicality and insight into the state’s wildlife management strategies.

Iowa

Iowa ranks fourth in the nation for deer-vehicle collisions, with drivers facing a 1 in 68 chance of hitting a deer on the road. For those unlucky enough to encounter a roadside buck, Iowa law allows you to salvage the animal, but only after obtaining a free salvage tag. The process is straightforward: contact a conservation officer, state trooper, or sheriff, provide details about the accident, and receive authorization to take the deer home. Whoever hits the deer gets priority to claim it, but if they pass, it’s fair game for anyone else. However, there’s one catch: you must take the entire carcass. No cutting off antlers or leaving behind unwanted parts in the ditch.

While salvaging roadkill might not sound glamorous, it’s surprisingly practical in Iowa. A single deer can yield up to 70 pounds of venison, perfect for stocking freezers during hunting season. Some residents even turn their finds into creative meals inspired by roadkill recipe books. Beyond filling plates, Iowa’s salvage system helps reduce waste and clear highways of hazards that could attract scavengers like vultures or coyotes. It’s not just about practicality, it’s about making use of nature’s accidents in a state where deer are as common as cornfields.

Kansas

Kansas takes a meticulous approach to roadkill salvage, requiring residents to obtain a salvage tag before claiming big game animals like deer or wild turkeys. The process is straightforward: contact the Kansas Department of Wildlife and Parks (KDWP) or a local law enforcement officer to report the incident and receive authorization. The tag ensures accountability and prevents misuse, such as poaching disguised as roadkill collection. However, salvagers must take the entire carcass, no cutting off antlers or leaving unwanted parts behind.

Kansas uses its salvage program not only to reduce waste but also to collect valuable data on wildlife collisions. Biologists analyze information from permits to identify high-risk areas and implement mitigation strategies, such as wildlife crossings or fencing, to protect these areas. While salvaging isn’t without its challenges, burst organs and tire-tread bruises are common, many Kansans see it as a practical way to access free-range protein while contributing to conservation efforts.

Kentucky

Kentucky’s roadkill salvage laws are as flexible as its winding country roads. If you hit a deer or witness someone else hitting one, you can legally claim the carcass, provided you contact a conservation officer or law enforcement for approval. Unlike other states, Kentucky doesn’t require a formal salvage tag in all cases; officers may jot down the details on a business card for your records. This informal approach makes salvaging quick and accessible, especially for rural residents who rely on free-range meat as an economical option.

Timing is critical in Kentucky’s humid climate, where decomposition sets in fast during warmer months. Salvagers must inspect carcasses for freshness, clear eyes, and firm flesh, which are good signs, while bloating or maggots mean it’s too late. For those willing to brave the mess of shattered bones and tire-tread bruises, salvaging roadkill offers both practicality and insight into the state’s abundant wildlife.

Louisiana

Louisiana’s roadkill salvage system is as unique as its Cajun culture. Residents can’t simply pick up a carcass off the road; instead, they must contact the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries (LDWF) to obtain a “donation form.” This form enables individuals to own and care for the animal for personal use legally. If the driver involved in the collision doesn’t want the carcass, LDWF steps in to retrieve it and donates the meat to local charities. The process ensures that nothing goes to waste while maintaining strict oversight to prevent misuse of wildlife resources.

With Louisiana’s warm climate, salvagers need to act fast; decomposition happens quickly, especially in the humid summer months. Popular salvaged animals include deer and wild hogs, which are often turned into hearty dishes like venison gumbo or smoked pork sausage. However, protected species like black bears or migratory birds are strictly off-limits. For Louisianans willing to navigate the paperwork and brave the mess of processing roadkill, it’s a way to turn an unfortunate accident into a delicious feast while supporting community food programs.

Maine

Maine’s roadkill salvage laws are as rugged as its northern forests. Residents can legally claim most animals hit by vehicles, including deer, moose, and bear, but only after obtaining a transportation permit from a game warden or law enforcement officer. Smaller animals, such as raccoons and porcupines, can be salvaged without much hassle, although protected species like bald eagles and hawks must remain where they fall. Maine’s approach is practical: why let fresh meat go to waste when it can feed families?

Timing is everything in Maine’s unpredictable climate. Winter’s freezing temperatures preserve carcasses longer, but summer heat accelerates decomposition quickly. Salvagers must inspect the animal for signs of freshness, clear eyes, and firm flesh, which are essential before processing it into meals like venison stew or moose burgers.

Maryland

Maryland’s roadkill salvage laws are practical but tightly regulated. Residents can claim deer and smaller game animals like squirrels or raccoons, but only with a hunting permit issued by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources (DNR). If the animal involved is a black bear, salvagers must notify DNR immediately for special handling. These rules ensure accountability while preventing poaching disguised as accidental collection. For drivers involved in collisions, the process is straightforward: report the incident, obtain approval, and take the entire carcass home for personal use.

Maryland’s humid climate makes timing critical; salvagers need to act fast before decomposition sets in. Clear eyes and firm flesh indicate freshness, while bloating or discoloration means it’s too late. Processing roadkill isn’t glamorous, think tire marks and ruptured organs, but for those willing to stomach the mess, it’s a way to access free-range protein while reducing waste. Some Marylanders even turn their finds into creative dishes, such as venison chili or squirrel stew, blending resourcefulness with culinary ingenuity.

Massachusetts

Massachusetts takes a cautious approach to roadkill salvage, requiring residents to obtain a hunting permit and submit the carcass for inspection before taking it home. Deer are the most commonly salvaged animals, especially during mating season when collisions spike on suburban roads. Smaller animals like raccoons and squirrels can also be claimed, but only if they meet strict freshness criteria. The Massachusetts Environmental Police oversee the process to ensure that salvaged meat is safe for consumption and that no poaching is disguised as accidental collection.

Unlike states with lenient laws, Massachusetts enforces rules to prevent waste and ensure public safety. Salvagers must act quickly, as decomposition sets in fast during the state’s humid summers. Clear eyes and firm flesh are essential signs of freshness, while cloudy eyes or bloating signal spoilage. For those willing to navigate the red tape and brave the mess of processing roadside finds, salvaging roadkill offers a unique way to access organic meat while contributing to wildlife management efforts.

Michigan

Michigan makes turning roadkill into dinner surprisingly easy. Residents can salvage deer and bear killed in vehicle collisions by obtaining a free permit online or over the phone within 24 hours of collection. Drivers involved in the crash get first dibs, but if they pass, anyone else can step in to claim the carcass. With frigid winters acting as nature’s freezer, salvagers often have extra time to process their finds safely. A single deer can yield enough venison to fill a freezer, making roadkill salvage a thrifty option for families looking to stretch their grocery budgets.

But it’s not all smooth sailing or clean eating. Salvagers must inspect carcasses for clear eyes and firm flesh before diving into the mess of shattered bones and ruptured organs. Chronic wasting disease (CWD) is a growing concern in Michigan’s deer population, so heads from salvaged animals may need testing before consumption is deemed safe. Despite the goo and gore, many Michiganders embrace roadkill as an ethical way to reduce waste while scoring free-range protein. Some even donate their finds to food banks, proving that one person’s highway horror can be another’s hearty meal.

Mississippi

Mississippi’s roadkill salvage laws are a mix of practicality and regulation, reflecting the state’s rural roots and abundant wildlife. Residents can claim most animals killed in vehicle collisions, including deer, but only if they hold a valid hunting or trapping license. The rules are specific: the animal must be in season for hunting, and protected species, such as bobcats, otters, and migratory birds, are strictly off-limits. If the driver doesn’t want the carcass, others with the proper license can step in to claim it.

Mississippi’s warm climate makes timing critical; salvagers must act quickly to ensure the meat hasn’t spoiled. Clear eyes and firm flesh indicate freshness, while bloating or discoloration signal it’s too late. For those willing to brave the mess of processing roadside finds, salvaging roadkill offers a practical way to stock freezers with venison or wild hog meat. Beyond personal use, the practice helps reduce waste and clears highways of hazards that could attract scavengers, such as vultures or coyotes.

Missouri

Missouri keeps its roadkill salvage process simple: hit a deer, report it within 24 hours, and you’re good to go, as long as you have permission from the Missouri Department of Conservation (MDC). Deer are the most commonly salvaged animals, especially during mating season when collisions spike on rural highways. Salvagers must act quickly in Missouri’s humid climate, where decomposition works fast. Clear eyes and firm flesh are key indicators that the meat is still edible; bloating or maggots mean you’ve missed your chance.

For rural Missourians, salvaging roadkill isn’t just practical, it’s tradition. A single deer can provide enough meat for weeks of venison chili or jerky, but processing isn’t for the squeamish. Tire marks on fur, bloodshot meat from impact wounds, and shattered bones are part of the package. Cooking thoroughly eliminates health risks, such as parasites or bacteria that may be lurking in the flesh. Despite the “ick” factor, many Missourians see roadkill as a sustainable way to turn roadside accidents into hearty meals.

Montana

Montana has adopted roadkill salvage as a practical solution to reduce waste and provide residents with free-range meat. Since 2013, the state has allowed the salvage of deer, elk, antelope, and moose killed in vehicle collisions. Residents must obtain a free “Vehicle-Killed Wildlife Salvage Permit,” which can be acquired online or through law enforcement officers after the crash. Interestingly, you don’t need the permit before taking possession of the animal; it can be obtained within 24 hours after collecting the carcass. This flexibility makes Montana’s system one of the most accessible in the country.

Montana’s salvage program isn’t just about feeding families, it’s also about managing wildlife populations and tracking collision hotspots. The state requires salvagers to remove the entire carcass from the site to prevent attracting scavengers, such as bears or coyotes. Field dressing is allowed near the site, but must be done carefully to avoid leaving parts behind.

Nebraska

Nebraska’s roadkill salvage laws are highly organized, ensuring that no animal goes to waste while maintaining strict oversight. Residents can legally claim deer, antelope, or elk killed in vehicle collisions by obtaining a free salvage permit from the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission or a local sheriff’s office. The process is straightforward: report the incident within 24 hours and tag the carcass within 48 hours. The permit must include detailed information such as the species, sex, and age of the animal, as well as the location and time of the accident.

The state prioritizes who can claim roadkill. The driver involved in the collision gets first choice, followed by public institutions, non-profits, and finally other individuals. While salvagers are required to take the entire carcass, they can legally sell parts like hides, hooves, bones, horns, and antlers. However, selling or trading meat is strictly prohibited. Nebraska uses data from salvage permits to monitor wildlife populations and identify collision hotspots.

New Hampshire

New Hampshire’s roadkill salvage laws are refreshingly straightforward: if you’re a state resident and you hit a deer, you can legally claim it—no permits required. The driver involved in the collision has first dibs. Still, if they pass, local authorities or the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department will offer the carcass to other interested residents. This practice ensures that no animal goes to waste while limiting the spread of diseases by keeping salvaged meat local. Some towns even have lists of volunteers who process roadkill and donate the meat to families in need.

Take Bill Terry of Barrington, for example. Over the years, he’s salvaged six deer and turned them into meals for donation. “If the deer carcass sits on the side of the road, it creates coyote problems,” Terry explained. “I’d rather put it to good use.” For New Hampshire residents willing to roll up their sleeves, salvaging roadkill is a practical way to reduce waste while contributing to community efforts.

New Jersey

New Jersey’s roadkill salvage laws are as densely packed with rules as the state itself. Residents can legally claim deer killed in vehicle collisions, but only after obtaining a free permit from local police or a regional Fish and Wildlife office. The permit is valid for 90 days and allows the salvager to keep the meat for personal use, but not the antlers, which must be surrendered. This restriction aims to prevent poaching disguised as accidental collection. Wrapped venison packages must also be labeled with the permit number for accountability.

Deer collisions are prevalent during rutting season in the fall, when bucks are more active and less cautious near highways. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) monitoring is a priority in New Jersey, so heads from salvaged deer may need to be submitted for testing to ensure the safety of the meat. While salvaging roadkill may seem unconventional in a state more associated with diners than DIY venison, it’s a practical solution for reducing waste and providing free-range protein to those willing to follow the rules.

New Mexico

New Mexico’s roadkill laws are all about permission and process. Residents can’t simply pick up a carcass; they must first contact a local conservation officer to obtain approval. Once the officer assesses the situation, they issue a receipt granting legal possession of the animal. The funds collected from these transactions are deposited into the Game Protection Fund, which supports wildlife conservation efforts throughout the state. Deer are the most commonly salvaged animals, particularly in areas like Highway 264 near Gallup, where reclaimed mining lands provide prime deer habitat.

For those willing to navigate the red tape, salvaging roadkill in New Mexico is a practical way to utilize free-range protein while reducing waste. However, it’s not without its challenges. The arid climate accelerates decomposition, so salvagers must act quickly to ensure the meat is still safe to consume. Clear eyes and firm flesh are good indicators of freshness, while bloating or discoloration signals it’s too late.

New York

New York’s roadkill salvage laws are as diverse as its wildlife. Residents can legally claim deer, bear, and other animals killed in vehicle collisions, but only with a salvage tag issued by law enforcement or the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC). The driver involved in the crash has priority to take the animal, but if they decline, others can step in to claim it. Smaller mammals like raccoons and squirrels require a separate DEC-issued permit for collection.

While salvaging is legal, intentionally hitting an animal with a vehicle is strictly prohibited. With an estimated one million animals killed on U.S. roads every day, salvaging provides a way to make use of fresh meat that would otherwise rot. Some New Yorkers even turn their finds into creative meals, such as venison stew or squirrel pot pie.

North Carolina

North Carolina’s roadkill salvage laws are practical but come with a few quirks. Residents can legally claim deer and smaller animals like squirrels, rabbits, and raccoons, but only if they register the carcass over the phone with the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission. For furbearers like opossums and coyotes, salvaging is permitted only during the open hunting or trapping season and requires a valid license. However, federally protected species such as migratory birds are strictly off-limits. The state’s approach ensures accountability while allowing residents to utilize animals that would otherwise be wasted.

For those willing to navigate these rules, roadkill salvage offers more than just free meat; it’s a way to turn unfortunate roadside encounters into practical resources. Some North Carolinians even experiment with recipes like rabbit pot pie or squirrel stew, blending culinary creativity with a commitment to sustainability. Beyond food, salvaged fur-bearers are often skinned and their pelts sold, adding an economic incentive to the practice.

North Dakota

North Dakota allows residents to salvage roadkill, but there’s a catch: you’ll need a hunting permit to claim deer or other wildlife struck by vehicles legally. These permits are free and can be obtained from local game wardens or law enforcement offices. The state requires salvagers to report the collision and provide details about the incident, ensuring accountability while preventing misuse. Interestingly, you’re not required to report hitting an animal unless there’s injury or significant property damage, making roadkill salvage a relatively low-bureaucracy process compared to other states.

For rural North Dakotans, salvaging roadkill is both practical and culturally accepted. Winter temperatures often preserve carcasses naturally, giving salvagers more time to process their finds safely. However, summer heat accelerates decomposition quickly, making freshness checks essential before diving into the mess of shattered bones and tire-tread bruises. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is monitored closely in the region, so heads from salvaged deer may need testing before consumption is deemed safe.

Ohio

Ohio keeps its roadkill salvage rules simple: if you hit a deer or other wildlife on the road, you can legally claim it without much red tape. Residents must report their find to local authorities before taking possession of the carcass, ensuring accountability while helping wildlife officials track collision hotspots across the state. Deer are the most commonly salvaged animals in Ohio due to frequent accidents during mating season in fall when bucks are more active near highways.

Roadkill salvage in Ohio isn’t just about practicality; it’s also about reducing waste and clearing hazards from busy roadsides. A single deer can yield enough venison for weeks of meals like stew or chili, making it an economical option for families looking to stretch their food budgets. Many Ohioans embrace roadkill as an ethical way to make use of nature’s accidents while contributing to conservation efforts.

Oklahoma

Oklahoma’s roadkill salvage laws are straightforward but require proper documentation. Residents can legally claim roadkill, such as deer, elk, or pheasants, as long as they obtain a “non-legal kill receipt” from a local game warden. This receipt acts as a permit, allowing individuals to possess the carcass for personal use. However, the process can be slow due to limited numbers of game wardens, meaning salvagers risk losing edible meat while waiting for approval. Without the receipt, salvaging roadkill is treated as poaching, with violators facing legal consequences.

The law applies to any game animal with a regulated hunting season, ensuring accountability and compliance with wildlife management rules. While some rural residents skip the paperwork and take their chances, others see roadkill salvage as a practical way to save money on groceries.

Oregon

Oregon has turned roadkill salvage into an organized affair since legalizing it in 2019. Residents can claim deer and elk killed on highways by obtaining a free online permit within 24 hours of collection. But there’s a catch: Salvagers must turn in heads and antlers to state Fish and Wildlife offices for chronic wasting disease (CWD) testing, a program that helps monitor wildlife health across Oregon’s sprawling landscapes. With over 3,100 permits issued in just two years, salvaging has become increasingly popular among Oregonians seeking to offset their grocery bills while reducing waste.

It’s not glamorous work; processing a carcass often means dealing with shattered bones and blood-soaked fur, but for many Oregonians, it’s worth it. Recipes like venison chili or elk jerky have become staples among those willing to embrace this unconventional practice. And while tire marks on meat might make some gag, others see roadkill as an opportunity to turn tragedy into sustainability.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania’s roadkill salvage program is one of the most active in the country, with over 3,300 permits issued annually. Residents can legally claim deer killed in vehicle collisions, but there are strict rules to follow. Salvagers must report the incident to the Pennsylvania Game Commission within 24 hours and obtain a free permit for personal use only; selling or trading the meat is prohibited. The head and antlers must be surrendered to the Commission, with disposal handled at designated dumpsters to prevent misuse or concerns about poaching.

The state’s salvage program isn’t just about reducing waste; it’s also a tool for wildlife management. Data collected from permits helps track collision hotspots and informs conservation strategies, such as fencing and wildlife crossings. For Pennsylvanians willing to brave shattered bones and tire-tread bruises, roadkill salvage offers an economical way to access venison while contributing to highway safety efforts. Whether turned into hearty meals or donated to food banks, salvaging roadkill reflects Pennsylvania’s practical approach to wildlife conservation.

Rhode Island

Rhode Island’s roadkill salvage system is tightly regulated, requiring residents to obtain a Wildlife Roadkill Salvage (WRS) permit within 24 hours of collecting an animal struck by a vehicle. The permit ensures accountability and provides valuable data on wildlife populations and collision hotspots across the state. Only particular species, like white-tailed deer, wild turkey, pheasant, and coyote, are eligible for salvage, while protected animals are strictly off-limits. Civilians cannot euthanize injured animals; only law enforcement officers can dispatch them for salvage purposes.

Salvagers must remove the entire carcass from the site, as leaving viscera behind violates state law and risks attracting more wildlife to dangerous roadways. Rhode Island uses its salvage program not just for waste reduction but also as a tool for conservation planning. By analyzing collision reports, officials can identify areas where wildlife crossings or fencing might be needed. For residents willing to follow the rules, salvaging roadkill offers both a sustainable food source and an opportunity to contribute to safer highways.

South Carolina

South Carolina’s roadkill salvage laws are practical but come with specific rules. Residents can claim deer and other non-protected species killed in vehicle collisions, provided they notify local wildlife officials. The state requires salvagers to report the incident to the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources (SCDNR) before taking possession of the carcass. Protected species, such as black bears or federally endangered animals, are strictly off-limits.

For rural South Carolinians, salvaging roadkill is seen as a resourceful way to access free meat. Deer are the most commonly claimed animals, especially during hunting season when collisions spike. While some residents turn their finds into meals, such as venison stew, others use salvaged animals for educational purposes or as subjects for taxidermy projects. The state’s approach strikes a balance between practicality and conservation, ensuring that no animal goes to waste while maintaining accountability and transparency.

South Dakota

South Dakota allows residents to salvage deer and antelope killed in vehicle collisions, but only after notifying a conservation officer or law enforcement official. A written authorization is required, which must remain with the carcass during processing or storage. This system ensures that salvaged animals are used responsibly while preventing poaching disguised as accidental collection.

The state’s wide-open highways and abundant wildlife make roadkill a common occurrence, particularly during migration seasons. For South Dakotans willing to navigate the paperwork, salvaging roadkill offers an economical way to stock freezers with venison or antelope meat. Beyond personal use, the state utilizes data from salvage permits to track wildlife-vehicle collisions and identify areas where mitigation efforts, such as fencing or wildlife crossings, could reduce accidents.

Tennessee

Tennessee’s roadkill laws are among the most straightforward in the country. Under state law (TCA 70-4-115), residents can claim wild game animals accidentally killed by vehicles as long as they notify the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA) or law enforcement within 48 hours. Deer are the most commonly salvaged animals, but bears can also be claimed with a receipt issued by the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency (TWRA). Smaller animals like squirrels and raccoons can be collected without formalities.

For Tennesseans, salvaging roadkill is a practical way to access free-range meat while clearing highways of hazards. Some residents turn their finds into creative dishes, such as raccoon barbecue or squirrel stew, embracing the state’s resourceful spirit. However, federally protected species like bald eagles remain off-limits. Tennessee’s approach reflects a balance between practicality and wildlife conservation.

Utah

Utah allows residents to salvage roadkill, provided they follow specific guidelines. The animal must not be a protected species—no bald eagles or endangered critters here, and it is illegal to intentionally hit an animal with your vehicle to claim it as roadkill (yes, people have tried). Before taking possession of the carcass, salvagers must contact wildlife authorities for approval and ensure that proper documentation is in place. Antlers and horns cannot be kept, and selling salvaged meat is strictly prohibited.

Utah’s dry climate makes timing critical; decomposition sets in quickly under the sun, meaning salvagers need to act fast to avoid spoiled meat. Freshness indicators, such as clear eyes and firm flesh, are essential when deciding whether to process the animal. Despite the “ick” factor, some Utahns embrace roadkill as a sustainable source of protein and a way to reduce waste. Recipes like venison steaks or elk chili are popular among those willing to brave the mess of processing a carcass.

Vermont

Vermont’s roadkill salvage laws reflect its practical and community-driven spirit. Residents can claim deer or moose struck by vehicles, but must first call local game wardens to obtain a tag before removing the carcass from the roadside. Each tag includes a unique five-digit number tied to the specific animal, ensuring accountability and preventing poaching disguised as roadkill collection. Vermont’s informal distribution system has been in place for decades; wardens often offer salvaged meat to drivers first and then distribute it to food banks or families in need if the driver declines.

Not all animals make it from pavement to plate. Smaller creatures like squirrels or raccoons rarely survive collisions with their internal organs intact, making them unsuitable for consumption. Vermont’s cold climate helps preserve larger carcasses longer during winter months, but summer heat accelerates decomposition significantly. Salvagers must inspect animals carefully for signs of freshness, clear eyes, and firm flesh, which are good indicators, before processing them into meals like venison stew or moose burgers.

Virginia

Virginia’s roadkill salvage laws are practical and straightforward, allowing residents to claim deer killed in vehicle collisions. The driver involved in the accident has priority to take the carcass, but anyone else can step in with a salvage permit issued by local law enforcement or wildlife officials. The process requires reporting the incident and tagging the animal to ensure accountability. Salvagers can use the meat for personal consumption, but antlers and hides cannot be sold or traded under state law.

Virginia’s approach isn’t just about reducing waste; it’s also about safety. Clearing large animals, such as deer, from highways prevents further accidents and reduces hazards for other drivers. Salvaging is particularly common during rutting season in fall when deer activity spikes, leading to more collisions. For Virginians willing to process their finds, roadkill offers an economical way to stock up on venison while contributing to safer roads and wildlife management efforts.

Washington

Washington legalized roadkill salvage in 2016, making it one of the more recent states to embrace this practice. Residents can claim deer and elk killed in vehicle collisions by obtaining a free printable permit from the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). The permit must be secured within 24 hours of collecting the carcass, and salvagers are required to remove the entire animal, including entrails, from the roadside. However, roadkill salvage is prohibited in certain counties like Clark, Cowlitz, and Wahkiakum due to concerns about endangered species like the Columbia white-tailed deer.

Washington’s program has proven popular, with thousands of permits issued annually since its inception. Beyond reducing waste, the state uses salvage permits as a tool for monitoring wildlife health. Heads from salvaged animals are often tested for Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD), helping officials track potential outbreaks. For residents willing to follow the rules, salvaging roadkill offers a sustainable source of free-range meat while contributing to conservation efforts.

West Virginia

West Virginia leads the nation in deer-vehicle collisions, making its roadkill salvage laws both practical and necessary. Residents can legally claim deer struck by vehicles by reporting the incident within 12 hours to local law enforcement or wildlife officials. A free permit is required for possession, ensuring accountability and compliance with state regulations. Salvaging is particularly common during hunting season when deer activity near highways increases dramatically.

West Virginia’s approach isn’t just about practicality; it’s also part of its culture. The state even hosts an annual Roadkill Cook-Off in Marlinton, where chefs compete to create dishes inspired by roadside finds (though not actual roadkill). For those willing to brave tire marks and bruised meat, salvaging offers an affordable way to access venison while reducing waste on West Virginia’s rural roads.

Wisconsin

Wisconsin has made roadkill salvage both practical and efficient with its streamlined reporting process. Residents can claim deer, bear, or wild turkey killed in vehicle collisions by obtaining a free permit from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR). Previously, motorists had to wait for law enforcement to arrive on the scene to issue permits. Still, now they can call a dedicated DNR hotline, available daily from 7 a.m. to 10 p.m., to report the incident and receive authorization. For accidents involving smaller game animals, hunters can claim carcasses during the open season for that species without additional permits.

With an estimated 26,000 deer killed annually on Wisconsin roads, the state’s salvage program helps reduce waste while providing residents with access to free-range meat. The DNR uses data from these permits to monitor wildlife-vehicle collision hotspots and inform conservation strategies. For those willing to process their finds, including tire marks and roadkill, salvage in Wisconsin offers not just a practical solution but also a way to contribute to wildlife management efforts.

Wyoming

Wyoming’s roadkill salvage program is as modern as it is practical. Legalized in 2022, residents can now use the Wyoming 511 app to request authorization for salvaging animals like deer, elk, moose, antelope, wild bison, and wild turkey struck by vehicles. The app even works without cellular service, allowing users to document the incident and receive an electronic certificate on the spot. However, there are strict rules: salvagers must collect the entire animal, dispose of inedible parts at approved landfills, and avoid busy highways or national parks.

With an average of 6,000 big game animals killed annually on Wyoming roads, 85% of which are mule deer, the program helps reduce waste while collecting valuable data for wildlife management. The app tracks geotags and collision details, helping officials identify areas with high wildlife crossing activity or potential locations for fencing projects. For residents willing to follow the guidelines, salvaging roadkill offers a sustainable way to utilize high-quality meat while supporting conservation efforts across Wyoming’s vast landscapes.