What if you could stand face-to-face with creatures that roamed the Earth thousands or even millions of years ago? Thanks to rapid advances in genetic technology, this dream may not be as far-fetched as it once seemed. Around the globe, researchers are exploring the possibility of cloning ancient animals—not just to satisfy scientific curiosity but to better understand evolution and even restore lost ecosystems. Some of these creatures are so obscure they sound like legends, while others are well-known giants from prehistoric times. Let’s dive into this fascinating list of 17 dangerous ancient animals that scientists are considering bringing back to life.

1. Megalania

Flickr

Imagine encountering a 23-foot-long lizard weighing over 4,000 pounds—this was Megalania, also known as the “giant monitor lizard.” Native to Australia during the Pleistocene epoch, it was essentially a super-sized Komodo dragon with a venomous bite that made it the apex predator of its time. Reviving this colossal reptile could provide fascinating insights into Australia’s prehistoric megafauna and how such predators influenced their ecosystems. But let’s be real: reintroducing a predator of this size is not without serious risks. Could it coexist with modern wildlife? Would humans be safe? Bringing back Megalania might be a thrilling scientific feat, but it also feels like opening a Jurassic-sized can of worms.

2. Dunkleosteus

Flickr

If you think sharks are scary, meet Dunkleosteus, a prehistoric armored fish that ruled the seas 360 million years ago. This monstrous predator could grow up to 30 feet long, with jaws like guillotines—razor-sharp, self-sharpening edges that could slice through anything in its path. Dunkleosteus was the apex predator of its time, shaping marine ecosystems in ways we can only begin to imagine. Cloning this terrifying fish might help scientists uncover secrets about ancient food chains and marine evolution. Still, the idea of unleashing a sea monster like this in today’s oceans is chilling. Would it disrupt modern ecosystems, or is this one best admired as a fossil?

3. Andrewsarchus

Wikimedia Commons

Andrewsarchus wasn’t just another prehistoric carnivore; it was a beast of epic proportions. Living around 45 million years ago, this mammal was about the size of a horse but had a massive three-foot-long skull and bone-crushing jaws. As one of the largest terrestrial predators of its era, it played a crucial role in ancient ecosystems. Cloning Andrewsarchus could help scientists piece together its mysterious evolutionary links to modern carnivores. However, the limited fossil evidence makes this a tough challenge. Plus, its massive size and predatory nature make you wonder: where would it fit in today’s world? Fascinating as it is, this creature might be better left in the past.

4. Arthropleura

Wikimedia Commons

Imagine a millipede the size of a small car slithering through ancient forests—this was Arthropleura. At up to 8 feet long, it was the largest land invertebrate to ever exist, thriving during the Carboniferous period over 300 million years ago. Despite its intimidating size, Arthropleura likely fed on decaying plants, making it more of a gentle giant (at least by giant bug standards). Scientists are curious about how such creatures thrived in oxygen-rich ancient forests and what their role was in those ecosystems. Cloning Arthropleura might unlock these secrets, but let’s be honest: who really wants to run into an 8-foot bug on a hike?

5. Helicoprion

GoodFon

Helicoprion was a prehistoric shark-like creature with one of nature’s most bizarre features—a spiral-shaped jaw packed with serrated teeth. This “tooth whorl” looked like a circular saw and was perfect for slicing through prey. Living about 290 million years ago, Helicoprion is an evolutionary puzzle scientists are eager to solve. Cloning it could reveal how this strange adaptation helped it thrive in ancient oceans and what its role was in the marine food web. But even though it’s fascinating, its unsettling appearance means it might be a creature best appreciated in a museum exhibit rather than in the wild.

6. Short-Faced Bear

Flickr

The short-faced bear was no ordinary bear—it was a giant Ice Age predator that stood up to 12 feet tall on its hind legs. Built for both speed and strength, it likely dominated other predators and scavenged massive carcasses across North America. Scientists are intrigued by its mysterious diet and behavior, which remain largely speculative. Reviving this bear could help us understand Ice Age ecosystems and how megafauna adapted to climate change. But let’s face it, bringing back a predator of this size would require vast spaces and resources, not to mention raising serious concerns about human and wildlife safety.

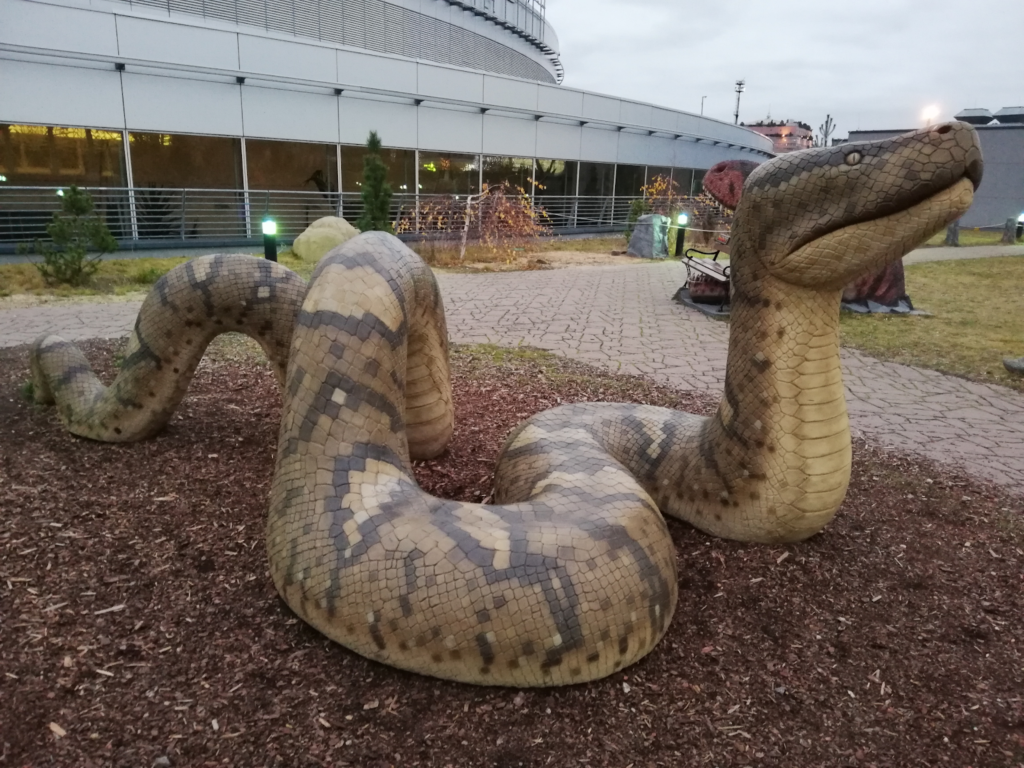

7. Titanoboa

Wikimedia Commons

If snakes give you the creeps, Titanoboa will haunt your dreams. This prehistoric serpent measured up to 50 feet long and weighed over a ton, making it the largest snake ever discovered. Titanoboa thrived in the sweltering swamps of what is now Colombia around 60 million years ago, feeding on crocodiles and giant fish. Cloning it could teach scientists about ancient climates and how reptiles adapted to them. But here’s the thing: would anyone feel safe knowing a snake this massive could exist again? While it’s an exciting prospect for science, most of us would rather admire Titanoboa from a very safe distance.

8. Thylacoleo (Marsupial Lion)

Wikimedia Commons

Thylacoleo, or the “marsupial lion,” was Australia’s answer to the big cats of the Ice Age. Despite its name, it wasn’t related to lions but had a fearsome set of adaptations, including powerful jaws, retractable claws, and a stocky build for ambush hunting. This predator likely preyed on large herbivores, filling a unique niche in Australia’s prehistoric ecosystem. Cloning Thylacoleo could provide insights into the continent’s lost megafauna and how it evolved in isolation. However, reintroducing such a predator raises questions: could it coexist with today’s species, or would it become a danger to both wildlife and humans?

9. Gorgonops

Wikimedia Commons

Long before dinosaurs, there was Gorgonops, a predator that walked the Earth 250 million years ago. This therapsid—a distant ancestor of mammals—was about the size of a large dog but had saber-like canine teeth that made it a deadly hunter. As a top predator of the Permian period, Gorgonops played a crucial role in shaping its ecosystem. Scientists believe cloning it could provide valuable insights into the evolutionary bridge between reptiles and mammals. But with its fearsome teeth and aggressive nature, Gorgonops might be one prehistoric creature best admired from the safety of a laboratory, not roaming free in the wild.

10. Smilodon (Saber-Toothed Cat)

Wikimedia Commons

Smilodon, the saber-toothed cat, is one of the most iconic predators of the Ice Age. Known for its massive build and dagger-like canine teeth, Smilodon was an ambush hunter, taking down large prey like bison and mammoths. It lived in the Americas until its extinction around 10,000 years ago, likely due to climate change and the loss of its food sources. Scientists believe cloning Smilodon could reveal more about its social behavior and interactions with other Ice Age animals. However, its predatory prowess and potential risks mean any attempt to revive it would need to be carefully managed.

11. Haast’s Eagle

Wikimedia Commons

Haast’s eagle was a true giant of the skies, boasting a wingspan of up to 10 feet and weighing over 30 pounds. Native to New Zealand, this apex predator specialized in hunting moa—giant, flightless birds many times its size. With razor-sharp talons and incredible strength, it was a fearsome predator until its extinction around 1400 CE, caused by the disappearance of its primary prey and human activity. Scientists are intrigued by the idea of cloning Haast’s eagle to study its hunting strategies and its role in ancient island ecosystems. However, bringing back a predator of this scale raises ethical and ecological concerns. Would it adapt to modern prey, or would its reintroduction disrupt fragile ecosystems? It’s a thrilling thought, but one that deserves caution.

12. Dire Wolf

Flickr

Dire wolves are more than just mythical creatures from Game of Thrones—these Ice Age predators were very real. Larger and sturdier than today’s gray wolves, dire wolves had powerful jaws designed for taking down massive prey, such as bison and mammoths. They roamed across North and South America before their extinction around 13,000 years ago. Cloning dire wolves could help scientists explore their relationship to modern wolves and uncover why they vanished. While they’re less intimidating than some of the creatures on this list, their reintroduction would still be tricky. Could they thrive in today’s world, or would they face the same fate as before?

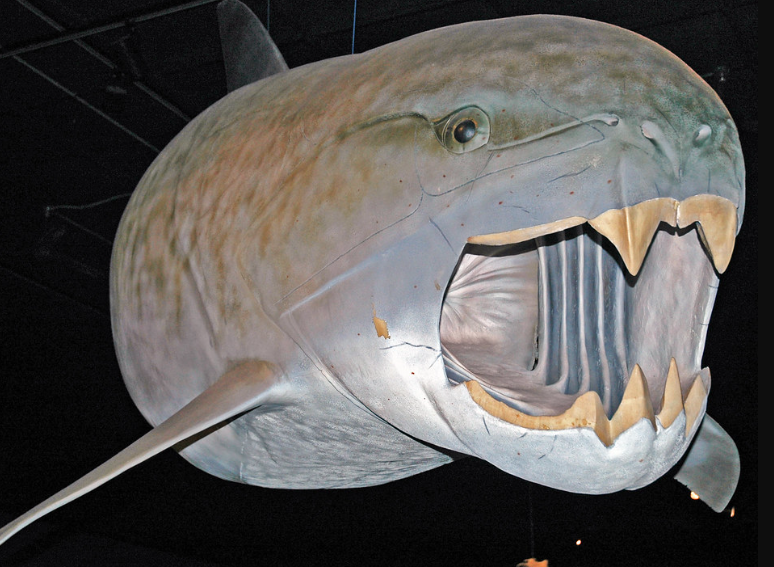

13. Megalodon

DeviantArt

Megalodon was the king of the oceans, a colossal shark measuring up to 60 feet in length. With teeth over 7 inches long, this apex predator fed on whales and other large marine animals, ruling the seas until its extinction around 3 million years ago. Reviving Megalodon could offer a glimpse into ancient marine ecosystems and help scientists understand how climate changes impact apex predators. But let’s be honest—releasing a predator of this magnitude into today’s oceans would be risky. Could modern marine life handle its presence? As fascinating as Megalodon is, the thought of sharing the water with a 60-foot shark might make even seasoned divers think twice.

14. Woolly Rhinoceros

Wikimedia Commons

The woolly rhinoceros was an Ice Age herbivore built to survive the cold, with its thick fur and stocky body making it perfectly adapted to freezing climates. Roaming alongside mammoths and saber-toothed cats, it grazed the tundras of Europe and Asia before going extinct around 10,000 years ago, likely due to climate change and human hunting. Scientists believe cloning the woolly rhinoceros could reveal how these animals thrived in such harsh environments and what caused their extinction. It could even aid in conservation efforts for modern rhino species, which are critically endangered. While less controversial than reviving predators, the ethical implications of bringing back this shaggy giant are still worth considering.

15. Quagga

Animalia

The quagga was a stunning subspecies of the plains zebra, with striking brown-and-white stripes on its front half that faded into solid brown on its rear. Sadly, overhunting led to its extinction in the late 19th century. As a relatively recent extinction, the quagga is a strong candidate for de-extinction since its DNA closely matches that of modern zebras. Reviving the quagga could help restore balance to South Africa’s ecosystems and serve as a symbol of conservation success. With its gentle temperament and ecological importance, this project is far less contentious than reviving a predator. However, questions remain about whether we can truly recreate the quagga or if it would just be a striped zebra stand-in.

16. Cave Lion

Flickr

The cave lion was a prehistoric big cat that dwarfed today’s lions in both size and strength. Roaming the plains of Eurasia and North America during the Ice Age, these massive predators hunted megafauna like reindeer and bison. Cloning cave lions could help scientists better understand extinct big cats, their social behavior, and their roles in Ice Age ecosystems. However, reintroducing such a predator presents major challenges. With modern habitats shrinking and human-wildlife conflicts on the rise, where would these lions live? While the thought of reviving a majestic creature like the cave lion is captivating, it also raises tough questions about coexistence in today’s world.

17. Woolly Mammoth

Wikipedia

Perhaps the most famous candidate for de-extinction, the woolly mammoth is already the subject of serious scientific efforts. These shaggy giants roamed the Arctic tundra, thriving in frigid climates thanks to their thick fur and unique adaptations. Some researchers believe reintroducing woolly mammoths could help restore grasslands in the tundra and slow permafrost thaw, potentially combating climate change. Reviving mammoths could also provide clues about their interactions with humans and other Ice Age species. But bringing them back isn’t without its controversies—caring for such massive creatures in the modern world poses ethical and logistical challenges. The woolly mammoth might hold promise for science, but its revival remains a topic of heated debate.

18. Moa

Wikimedia Commons

The moa, a group of giant flightless birds once native to New Zealand, vanished due to overhunting by humans around 600 years ago. These towering birds, some reaching heights of 12 feet, played a critical role in their ecosystem, acting as grazers and seed dispersers. Their extinction left a noticeable void in New Zealand’s biodiversity. Cloning the moa could help restore ecological balance and offer scientists valuable insights into how ancient island ecosystems functioned. However, reintroducing such large herbivores poses logistical challenges, such as finding suitable habitats and ensuring they don’t disrupt modern ecosystems. While the moa’s peaceful nature makes it less intimidating than other ancient creatures on this list, its revival still raises questions about whether such efforts could truly recreate the past.

The idea of reviving ancient animals is as thrilling as it is complex. Each species on this list offers a unique glimpse into the past, but the challenges of cloning—and the ethical dilemmas of reintroducing such creatures—make this field as controversial as it is fascinating. Which of these animals would you want to meet?