1. The Near Eastern Wildcat is the Primary Ancestor

The history of the domestic cat is far more complex and fascinating than a simple one-time event. Recent genetic and archaeological research has fundamentally challenged the traditional narrative, suggesting that our beloved, yet famously aloof, housemates may have actually been domesticated in two major, geographically distinct waves. All modern domestic cats, regardless of breed or location, are unified by their ancestry tracing back to a single subspecies: the Near Eastern wildcat, scientifically known as Felis silvestris lybica. This specific wildcat subspecies is naturally native to the semi-arid regions of North Africa and Southwest Asia, and its historical range precisely aligns with the geographical areas where the earliest and most profound signs of cat-human co-existence have been discovered. The sophisticated genetic analysis of ancient cat remains from various archaeological sites across the world as the undeniable maternal ancestor of every house cat alive today.

2. The First Domestication Began in the Fertile Crescent

The initial and foundational domestication event is inextricably linked to the advent of agriculture during the Neolithic Revolution in the Fertile Crescent, a crescent-shaped region spanning the Near East. Approximately 10,000 years ago, when early Neolithic farmers began the revolutionary practice of storing surplus grain in close proximity to their homes, they inadvertently created a readily available, concentrated food source for local rodent populations. This sudden abundance of prey naturally attracted the local, unaggressive wildcats, initiating a powerful and mutually beneficial commensal relationship where cats thrived on the rodents, and humans benefited from reduced pest damage to their vital food stores.

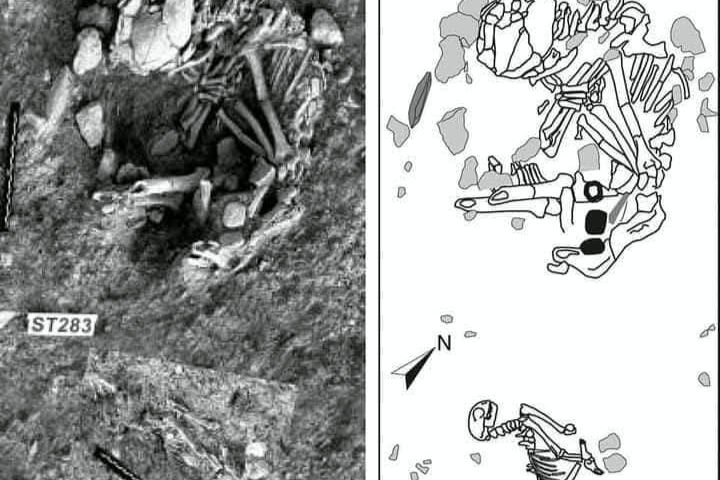

3. A 9,500-Year-Old Burial Site in Cyprus Provides Key Evidence

The earliest known and most compelling archaeological evidence of a close, deliberate human-cat relationship was unearthed on the island of Cyprus. A remarkably preserved burial site, dated precisely to around 7,500 BC (or approximately 9,500 years ago), contained the carefully interred remains of a human adult and an eight-month-old wildcat positioned deliberately in the same grave. The remarkably preserved burial site containing the deliberately interred remains of a human adult and an eight-month-old wildcat is located at the Neolithic village of Shillourokambos on the Mediterranean island of Cyprus. This grave, discovered by French archaeologists led by Jean-Denis Vigne. The findings challenge the previous belief that ancient Egyptians were the first to domesticate cats around 4,000 years ago.

4. Cats Were Initially Self-Domesticated

Unlike many other domesticated animals, such as dogs or various forms of livestock, the domestication of the cat was a largely spontaneous, self-selective process driven by behavior. Early humans did not actively or aggressively breed cats for specific traits like obedience, loyalty, or even larger size. Instead, the tamest, least fearful, and most socially tolerant wildcats were simply the most successful at thriving near human settlements, benefiting exponentially from the plentiful rodent prey and the overall human tolerance, a form of natural selection occurring in a new, human-made environment.

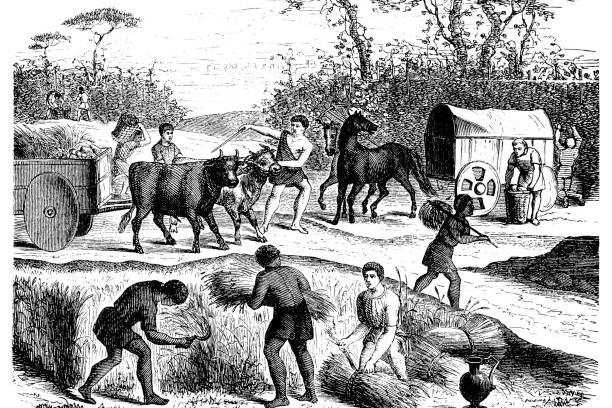

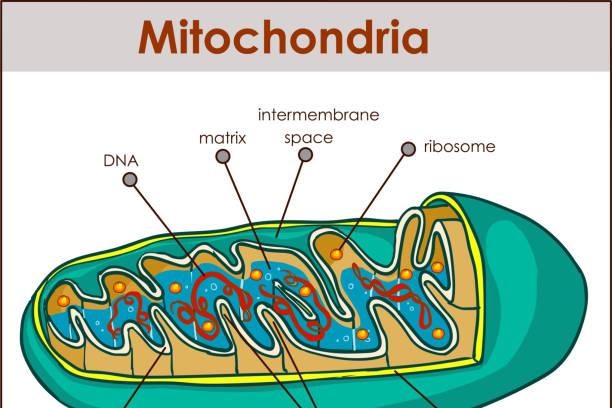

5. First Wave Spread with Neolithic Farmers

The first distinct genetic lineage of domesticated cats, meticulously identified by scientists as Mitochondrial DNA lineage IV-A, began its slow but steady spread out of the Near East approximately 6,000 years ago. This geographical expansion is directly correlated with the diaspora of early farming communities moving into Europe and other territories. The cats almost certainly traveled alongside the farmers, serving a vital and irreplaceable role as natural, effective pest controllers for their valuable and necessary grain stores, thereby allowing the cats to accompany and successfully colonize new territories across the continent.

6. Ancient Egypt Represents the Second Major Domestication Wave

While the initial domestication event, the formation of the basic species, occurred in the Fertile Crescent, a second, incredibly powerful wave of cat dispersal and cultural elevation originated in ancient Egypt. This wave, which occurred much later, roughly between the 8th century B.C. and the 5th century A.D., contributed profoundly to the genetic diversity and the global spread of the modern domestic cat, cementing their iconic status in human history.

7. Egyptian Cats Carried a Distinct Genetic Lineage

The cats from ancient Egypt carried a different but genetically related mitochondrial DNA lineage, often scientifically referred to as IV-C. This genetic signature, which likely originated from a localized group of local African wildcats, was intrinsically associated with the powerful expansion of cats across the entire Mediterranean world. This difference suggests a geographically separate, highly successful “taming” or cultural integration event in the fertile Nile Valley, which resulted in a robust and culturally prized cat population.

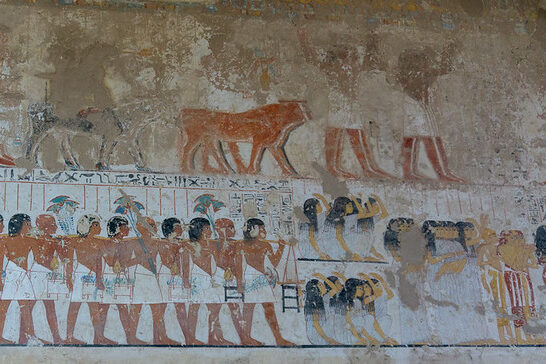

8. Egyptian Culture Elevated Cats to Divine Status

The Egyptians revered cats perhaps more than any other civilization in history, elevating them from simple pest controllers to sacred, protected animals. The important goddess Bastet was frequently depicted as a woman with the head of a lion or, later and more commonly, a house cat, symbolizing protection, fertility, and grace. This intense cultural value led to the active breeding, mummification, and careful, ritualistic burial of millions of cats, which further cemented their role in human society and ultimately encouraged their massive proliferation and success.

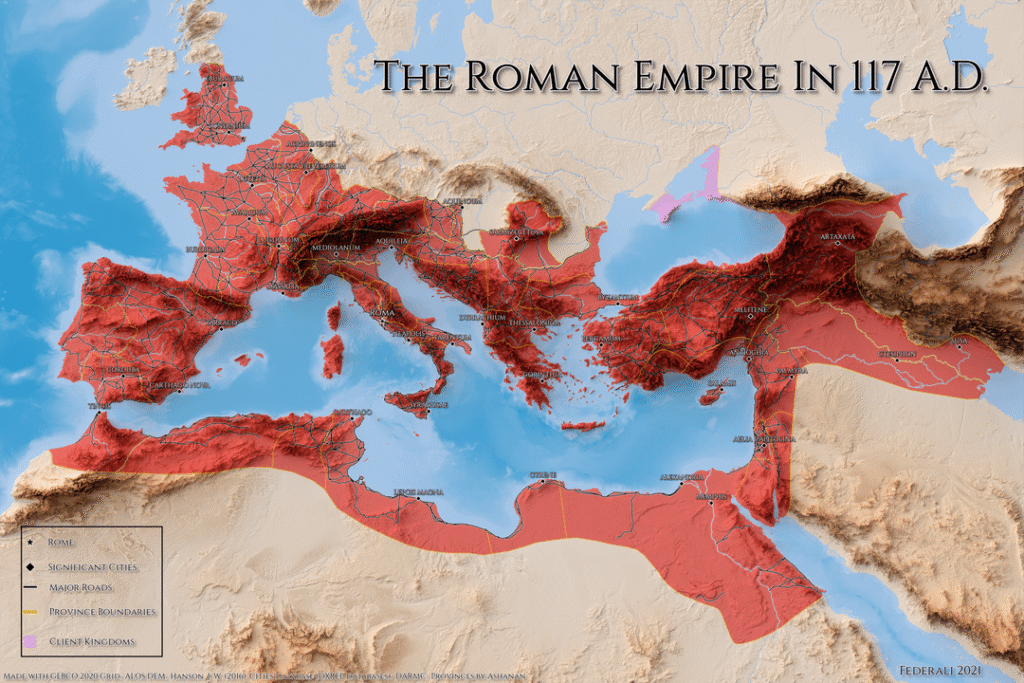

9. Roman Empire Aided the Global Spread

The massive and sustained expansion of the Roman Empire played a pivotal and final role in the second, Egyptian-led dispersal of domestic cats. As Roman legions traveled and maritime trade routes connected large parts of Europe, the Near East, and North Africa, cats, highly prized for their reliable rodent-catching abilities on military ships and within vast imperial granaries, were systematically carried to new continents. This organized movement helped the Egyptian genetic lineage quickly become the dominant and widespread cat population across the entire Old World.

10. The Original Wildcat is Now Endangered by Hybrids

Today, the African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), the direct and noble ancestor of all domestic cats, faces a serious and subtle threat to its genetic purity in certain regions. Where the wildcat’s territory significantly overlaps with the territory of domestic or feral cats, frequent and uncontrolled interbreeding occurs, creating hybrid offspring. This ongoing, pervasive process of hybridization can lead to the slow, steady loss of the wildcat’s distinct, unique genetic identity, which makes its conservation a far more complex and challenging task for scientists.

11. Early Domestication Did Not Change Cat Appearance

Unlike dogs, whose skulls, body size, and overall morphology were significantly and quickly altered during their domestication from wolves, the first domestic cats were physically almost completely identical to their wild relatives. The lack of intensive, directed artificial selection by early humans meant that, for thousands of years, the domestic cat’s only major difference from the wildcat was a purely behavioral one, a crucial reduction in the fear of humans and a basic acceptance of human proximity and shelter.

12. The Tabby Coat Pattern Emerged in the Middle Ages

The distinct and varied coat patterns we commonly associate with domestic cats today were surprisingly not a feature of the earliest domesticated felines. Genetic analysis of ancient DNA clearly shows that the distinct blotched or classic tabby pattern first arose from a spontaneous and relatively recent genetic mutation in Western Turkey sometime around the Middle Ages, likely in the 14th century. This specific development suggests that humans only began to consciously select and breed for aesthetically pleasing appearance traits much later in the long, drawn-out domestication process.

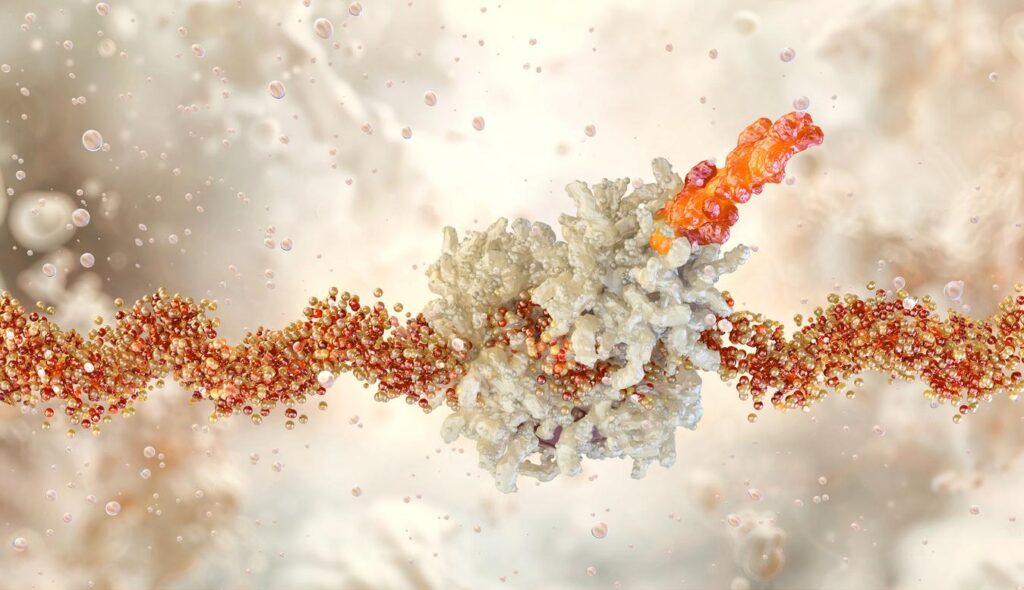

13. Genetic Changes Primarily Affect Behavior

In-depth molecular research comparing the entire genomes of domestic cats and their wildcat counterparts indicates that the most crucial evolutionary changes that occurred during their domestication involved specific genes related to behavior, memory, and fear-conditioning responses. These crucial genetic shifts likely supported the cats’ fundamental tolerance for complex human interaction, their acceptance of being handled, and their overall ability to thrive and reproduce successfully in a human-dominated, urbanizing environment, rather than purely physical characteristics.

14. Cats Were Never Truly Industrialized for Utility

While dogs were aggressively bred and specialized for specific human tasks like hunting, herding, tracking, or guarding, cats were largely accepted and valued for a single, natural, and highly effective skill: pest control. This fundamental difference in utility-driven breeding explains why cats have universally retained significantly more of their ancestral wild behaviors and traits compared to dogs. Their primary value was their intrinsic hunting ability, which required little direct human training or selective, intense breeding pressure.

15. The Chinese Cat Hypothesis Was Largely Debunked

For a short period, skeletal remains found at Neolithic sites in Quanhucun, China, tentatively suggested a third, independent domestication event from the local, indigenous leopard cat (Prionailurus bengalensis). However, later and more definitive mitochondrial DNA analysis of those same ancient remains conclusively revealed that the Chinese cats were actually Felis silvestris lybica, the Near Eastern wildcat. This finding robustly indicated the cats were imported, not locally domesticated, ultimately affirming the Near East as the single, core geographical origin for the domestic cat species.

16. The First Cats in Europe Arrived by Boat

The earliest definitive evidence of cats in Europe indicates they were brought across the water, likely as essential pest control agents aboard trading vessels and early maritime expeditions. The first dispersal wave of cats arriving from Anatolia spread into southeastern Europe, specifically documented in Bulgaria and Romania, by traveling with the expanding Neolithic farming communities, who greatly valued them for protecting irreplaceable grain stores both during transit and upon new settlement.

17. Viking Cats Traveled as Far as the Baltic Sea

During the second, highly successful wave of dispersal, the Egyptian genetic lineage of cats continued to spread far beyond the sunny Mediterranean. Archaeological finds of cat bones in Viking trading ports, such as Ralswiek on the chilly Baltic Sea coast in modern-day Germany, demonstrate that by the 7th century A.D., cats had become common, valued travel companions, proving their adaptability and continued utility even in the northern, often harsh, climates.

18. Domestication Is a Commensal Relationship

The entire process of cat domestication is best described by scientists as commensalism, a form of interaction where one species benefits greatly (the cat secured a reliable food source and shelter) and the other is neither significantly helped nor harmed (humans obtained passive, effective pest control). Initially, cats essentially domesticated themselves by successfully adapting to the new ecological niche created by human agriculture, which provided a reliable, concentrated food source in the form of rodents.

19. The Shortened Skull of Domestic Cats Evolved Late

While early domestic cats closely resembled their wild ancestors, one subtle physical change, a slightly but noticeably shortened skull, is a key morphological feature that distinguishes modern domestic cats. Skeletal remains from Roman-era Britain, dating to around the 4th century A.D., show the first tangible signs of this morphological change, suggesting that physical differentiation was an incredibly slow, gradual process that took millennia to become truly noticeable in the archaeological record.

20. Cats Have at Least Five Mitochondrial “Eves”

In-depth genetic studies have successfully traced the maternal lineage of domestic cats back to at least five distinct mitochondrial “Eves” among the Near Eastern wildcat population. This crucial finding suggests that the initial domestication event was not the result of the accidental or deliberate taming of a single female wildcat but rather the successful, independent incorporation of multiple local wildcat lineages from across the expansive Fertile Crescent region into the surrounding human environment.

21. Ancient DNA Confirmed the Two Dispersal Waves

A major, landmark 2017 scientific study involved the analysis of the mitochondrial DNA from 209 ancient cat remains, some astonishingly as old as 9,000 years, sourced from sites across Europe, Africa, and Asia, including numerous Egyptian cat mummies. This extensive and unprecedented genetic mapping was absolutely crucial in confirming the existence of the two distinct dispersal waves: the initial Neolithic spread from the Near East and the later, more widespread, and culturally driven dispersal of Egyptian cats during the Classical period.

22. Egyptians Mummified Cats in the Millions

The sacred and protected status of cats in ancient Egypt led to an extraordinary and unique cultural practice: ritual cat mummification. It is conservatively estimated that millions of cats were mummified and buried, often in vast, specialized cemeteries or sometimes lovingly interred with their high-status owners. These mummies, some of which provided invaluable samples for ancient DNA analysis, are a powerful and tangible testament to the intensity and depth of the human-feline bond in that specific ancient society.

23. Early Cats in Europe Maintained a Wild Presence

After the first wave of dispersal, the Near Eastern cat lineage did not immediately or universally dominate the European landscape. For thousands of years, the native European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) remained the locally dominant feline species, and the domestic cat’s presence was often confined almost exclusively to specific, isolated human settlements and trade routes, indicating a much slower initial integration into the established European natural environment.

24. Domestication Was Not a Single Event

The term “domestication” in the specific context of cats is now widely viewed by researchers as a prolonged, gradual, and in many ways, an ongoing process rather than a sudden, singular event of intentional taming. The initial attraction to human settlements was a behavioral adaptation by the wildcats themselves, followed by thousands of years of mutual tolerance, and only very recently has it involved deliberate selective breeding for arbitrary traits like coat color or specific body shapes.

25. The Abyssinian and Tabby Resemble the Wild Ancestor

Among the recognized modern domestic cat breeds, the Abyssinian and the mackerel tabby pattern most closely and faithfully resemble the physical appearance of their direct wild ancestor, the African wildcat. They share a similar slender, lithe build and the subtly striped or ticked “agouti” coat pattern that would have provided incredibly effective camouflage in the original Near Eastern savanna and desert environments, proving the strength of natural selection in their lineage.

26. Modern Breeds Are a Recent Development

The vast, diverse array of specific cat breeds seen and shown today, from the flat-faced Persian to the sleek, vocal Siamese, are a very recent phenomenon in the context of the cat’s 10,000-year history. It was not until the 19th century that cat fanciers and breeders began systematically breeding cats to aggressively select for specific, exaggerated physical traits, marking a definitive and total shift from natural selection to deliberate, intense artificial selection by humans.

27. The Wildcat’s Small Size Aided Domestication

One physical factor that scientists believe significantly aided the cat’s initial domestication was its relatively manageable size. Unlike large, potentially dangerous predators, the Near Eastern wildcat posed little to no direct threat to humans, making their presence around settlements easily and readily tolerated. This low-risk commensal relationship was foundational, allowing for a long period of coexistence without the pressure for immediate, forceful taming or eradication.

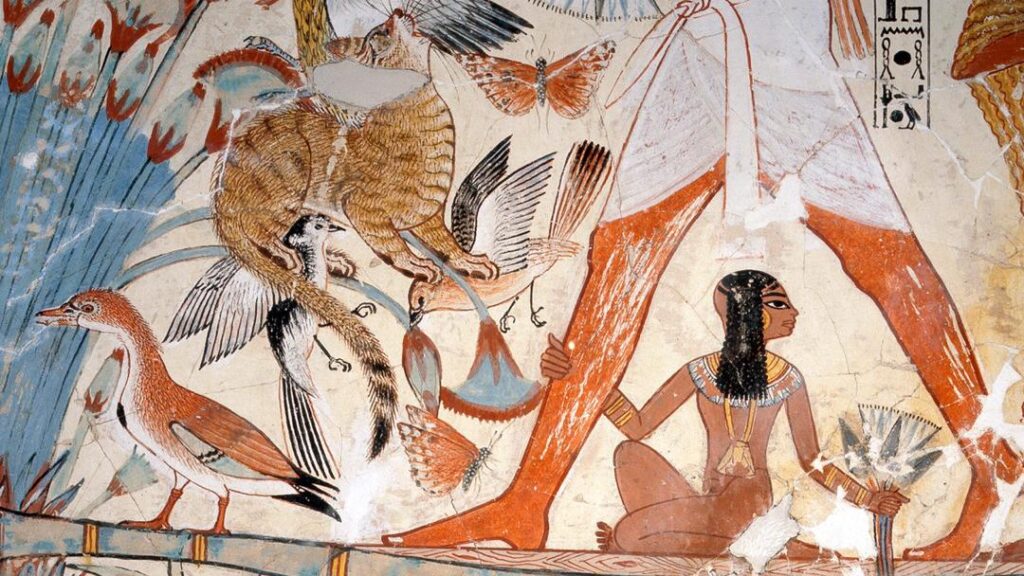

28. Early Art Depicts Cats as Hunters

In early Egyptian art, dating back to before 1500 BCE, cats are frequently and prominently depicted in their original functional role: efficiently catching birds and fish, often in marshy environments. It is only in later art, particularly highly detailed paintings from the New Kingdom onward, that cats are more commonly shown seated demurely under a woman’s chair or playing gently with children, signifying their evolving and elevated status as a cherished companion pet.

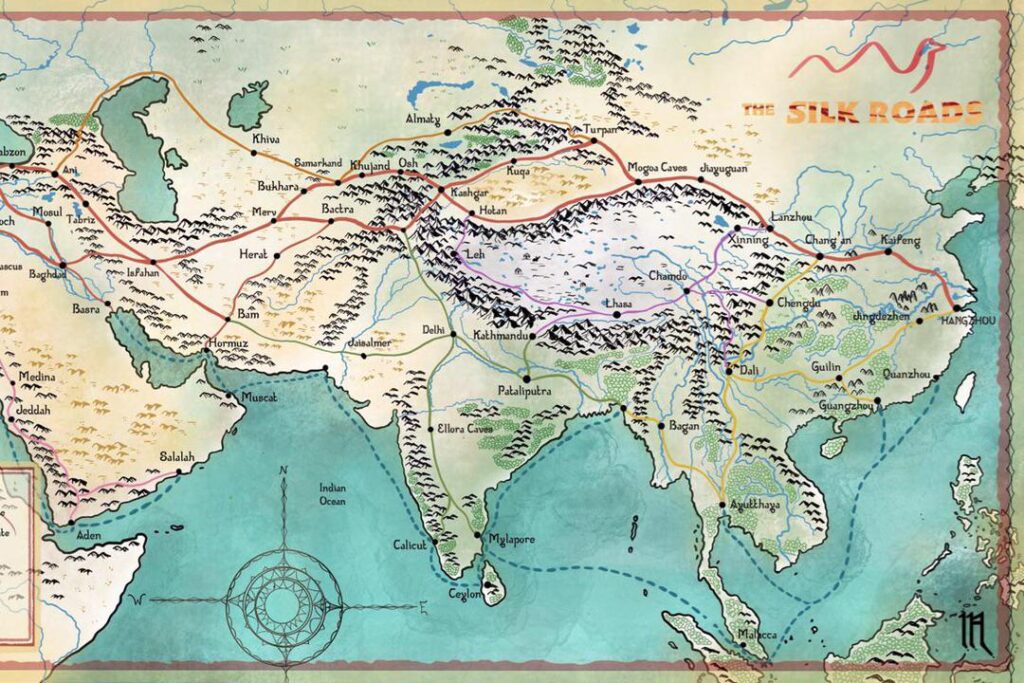

29. Cats Traveled the Silk Road

While often primarily associated with Mediterranean maritime trade routes, the successful spread of domesticated cats also undoubtedly followed the great overland trade networks, including the historic Silk Road. The compelling presence of cat remains in ancient Asian trading posts suggests they were either valuable commodities themselves or necessary, functional travelers, protecting vital goods from vermin over incredibly long, arduous distances, further contributing to their truly global reach.

30. Behavior is Still the Most Reliable Domestication Marker

Because the domestic cat’s skeleton and general appearance changed so little over the millennia of coexistence, the most reliable and enduring marker of successful domestication in the archaeological record remains its sustained presence in contexts directly associated with human activity, especially in areas where its wild ancestor would not have naturally lived. This behavioral shift, the voluntary and successful choice to live near humans, is the enduring and ultimate sign of its successful, unique domestication.

It is truly remarkable to think that the sleek, purring creature curled up comfortably on your sofa is the direct result of two great, ancient waves of natural selection, ecological opportunity, and human tolerance. They essentially chose us first, and their enduring success story is beautifully etched in the very DNA of every single purr.

This story Cats May Have Been Domesticated Twice, Researchers Say was first published on Daily FETCH