The true story behind the legend is stranger than fiction

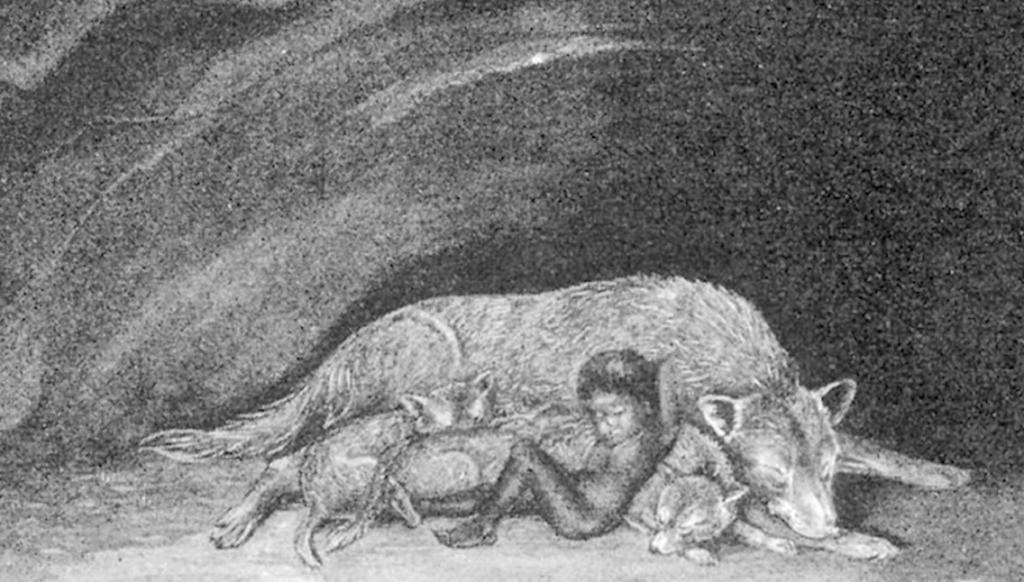

Some legends sound too wild to be true, like the story of a child surviving in the wild, nurtured not by humans but by wolves. But deep in colonial India in the 1800s, missionaries claimed to have discovered a boy running with wolves, snarling like an animal, and fleeing from people like prey. Was it a hoax? A misunderstood medical condition? Or something far more primal? Across continents and centuries, tales of “feral children” have captivated scientists and storytellers alike, and the real accounts are far stranger than the fictions they inspired.

This is the story of the boy raised by wolves and 14 facts that will make you question everything you thought you knew about human nature, animal instinct, and survival in the wild.

1. The legend begins in colonial India in 1867

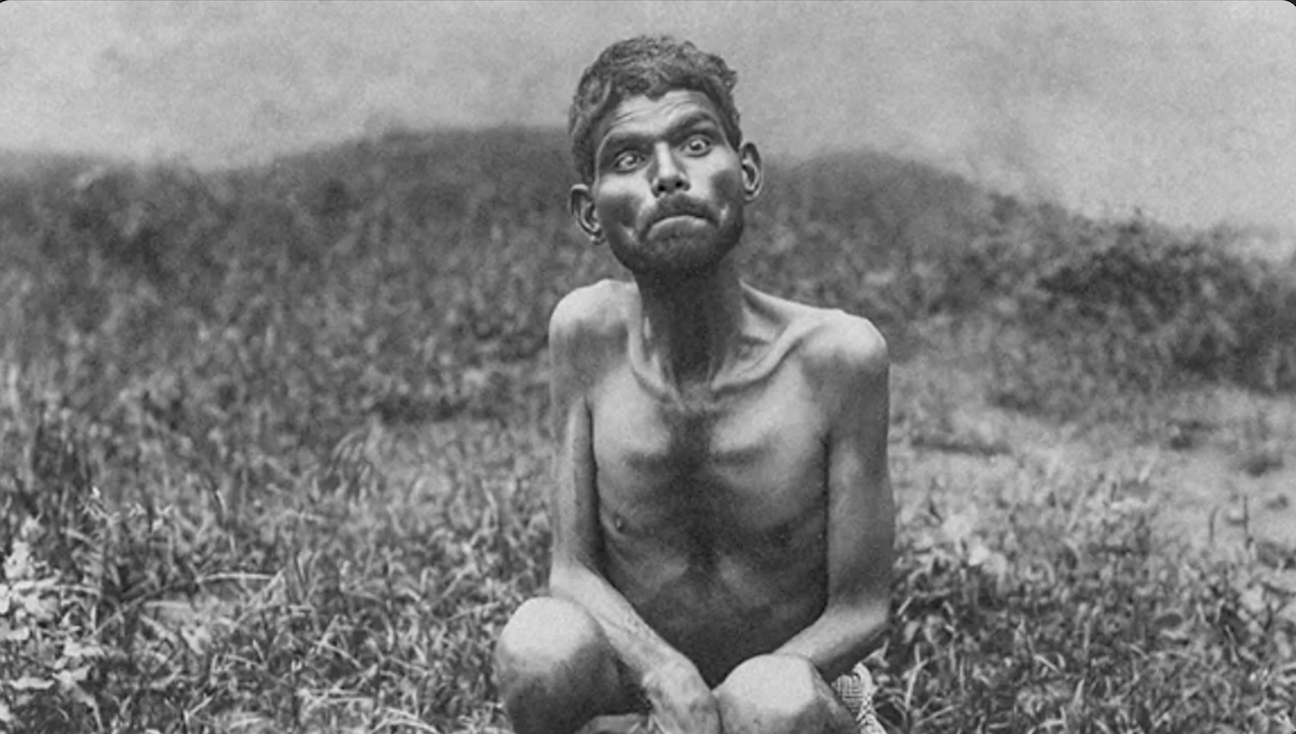

In the jungle near Bulandshahr, British missionaries claimed to have captured a naked, wild boy living with a pack of wolves. The child was said to run on all fours, growl instead of speak, and flee from people with animal-like agility. Locals had supposedly seen him for years, watching in awe as he moved alongside real wolves, hunched and fast. When the missionaries brought him to their orphanage, they named him Dina Sanichar. At first, he would only eat raw meat and showed no understanding of language, clothing, or human behavior.

Sanichar’s case baffled observers and soon spread across Europe as an example of a “feral child.” Though sensationalized by some papers, firsthand accounts from the orphanage described a boy with deep-set, distrustful eyes who chewed bones, snarled at caretakers, and could not be taught to speak. Some believe he may have had developmental delays before his time in the wild, but his preference for animal behavior over human norms remained until his death at age 34. Source: National Geographic

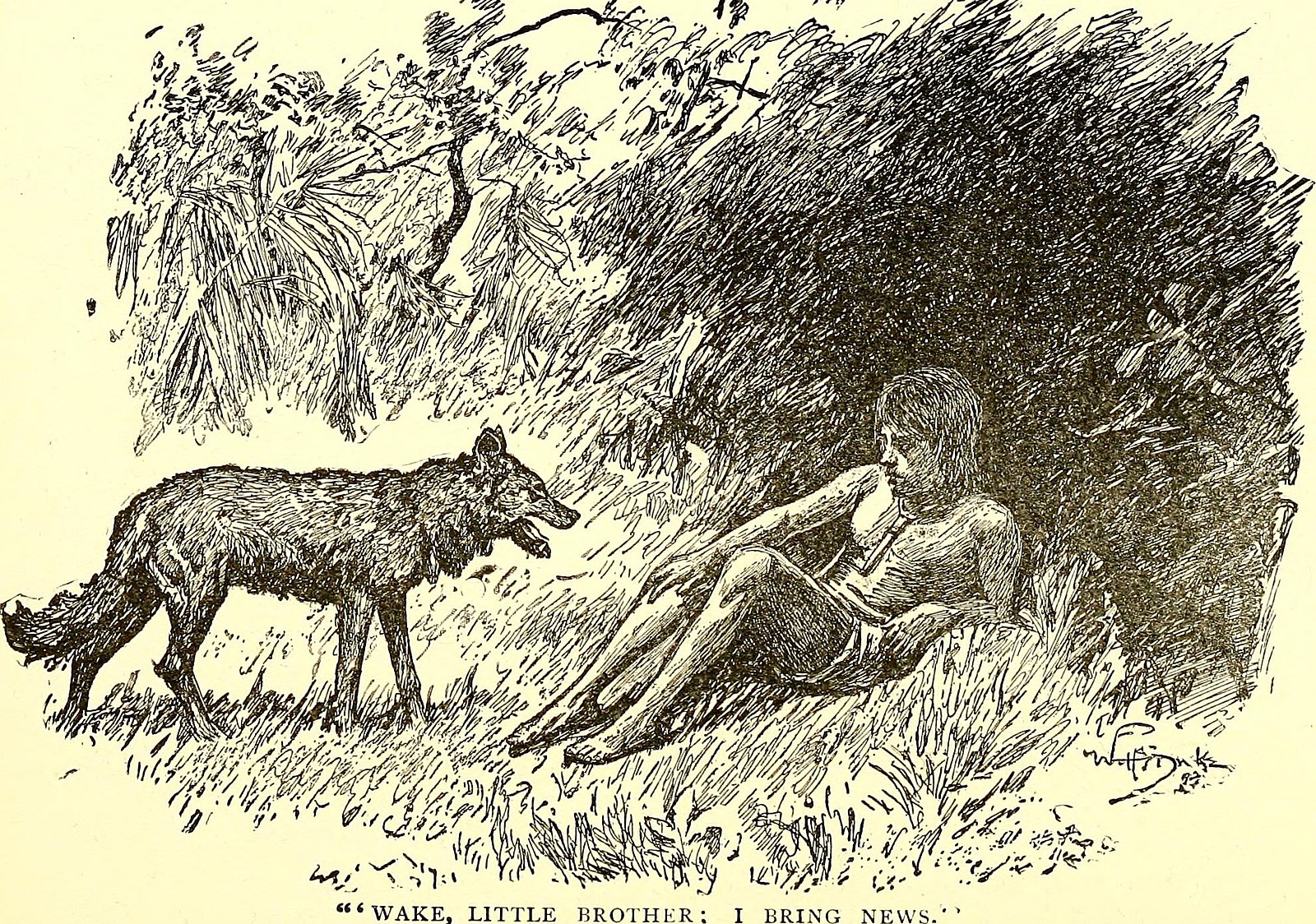

2. Dina Sanichar may have inspired Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book

While The Jungle Book was published in 1894, decades after Sanichar was discovered, many scholars believe Kipling drew inspiration from the real-life wolf boy. Kipling was born in India and lived in the country during the height of British colonial rule, just as Sanichar’s story made headlines. The idea of a child raised in the jungle by animals may have taken root from actual events. But unlike Mowgli’s eloquence and charisma, Sanichar remained nonverbal and animalistic for the rest of his life.

Interestingly, Kipling never publicly acknowledged Sanichar as inspiration. Still, the timing and proximity make the connection hard to ignore. Mowgli’s story romanticized jungle life and animal companionship, while Sanichar’s reality was far lonelier. He never bonded with other children at the orphanage and reportedly died of tuberculosis, ironically from exposure to the very human world that rescued him. Source: Medium

3. He never learned to speak—not a single word

Despite years of effort from caretakers, Dina Sanichar never developed the ability to speak or understand human language. Missionaries hoped to civilize him, but he remained mute, primarily communicating only through grunts, gestures, and animal-like behaviors. Some believed his brain had lost the capacity for language entirely—either from neglect or because he had passed the critical period of language acquisition. This developmental window closes by age 7. For Sanichar, the silence never lifted.

This aligns with research on other so-called “feral children,” who show that language, unlike walking or eating, must be learned in early childhood through social interaction. Sanichar’s case became a tragic example of what happens when a child is deprived of human contact in those formative years. Though he eventually learned to drink from a cup and wear clothes, speech never came. The window had closed, and with it, the human world remained out of reach. Source: All That’s Interesting

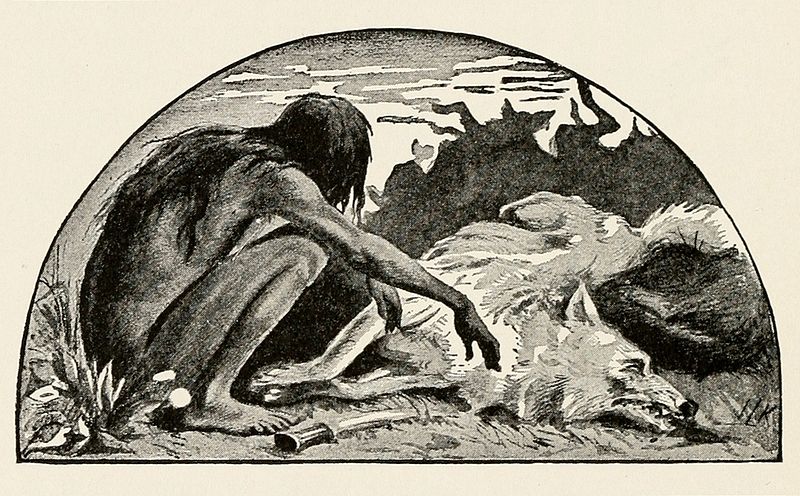

4. He walked on all fours for years after being rescued

When Sanichar first arrived at the orphanage, he refused to stand upright. Caretakers described how he moved swiftly on all fours, his palms and feet thickened like pads from years of crawling through the forest floor. He only stood when forced, and even then, his posture was stooped and unsteady. Unlike a child pretending to be an animal, Sanichar’s movement patterns seemed deeply ingrained and an adaptation to life in the jungle that had become his default.

Eventually, he learned to walk upright with persistent training, but it was always awkward and unnatural. This physical trait, so central to human identity, had eroded in him. The body remembers what the mind forgets, and for Sanichar, walking upright wasn’t just about balance or strength; it was about shifting worlds. The neurological rewiring that should’ve happened in early childhood had been bypassed by survival in the wild, leaving a permanent imprint on how he moved through life. Source: Bored Panda

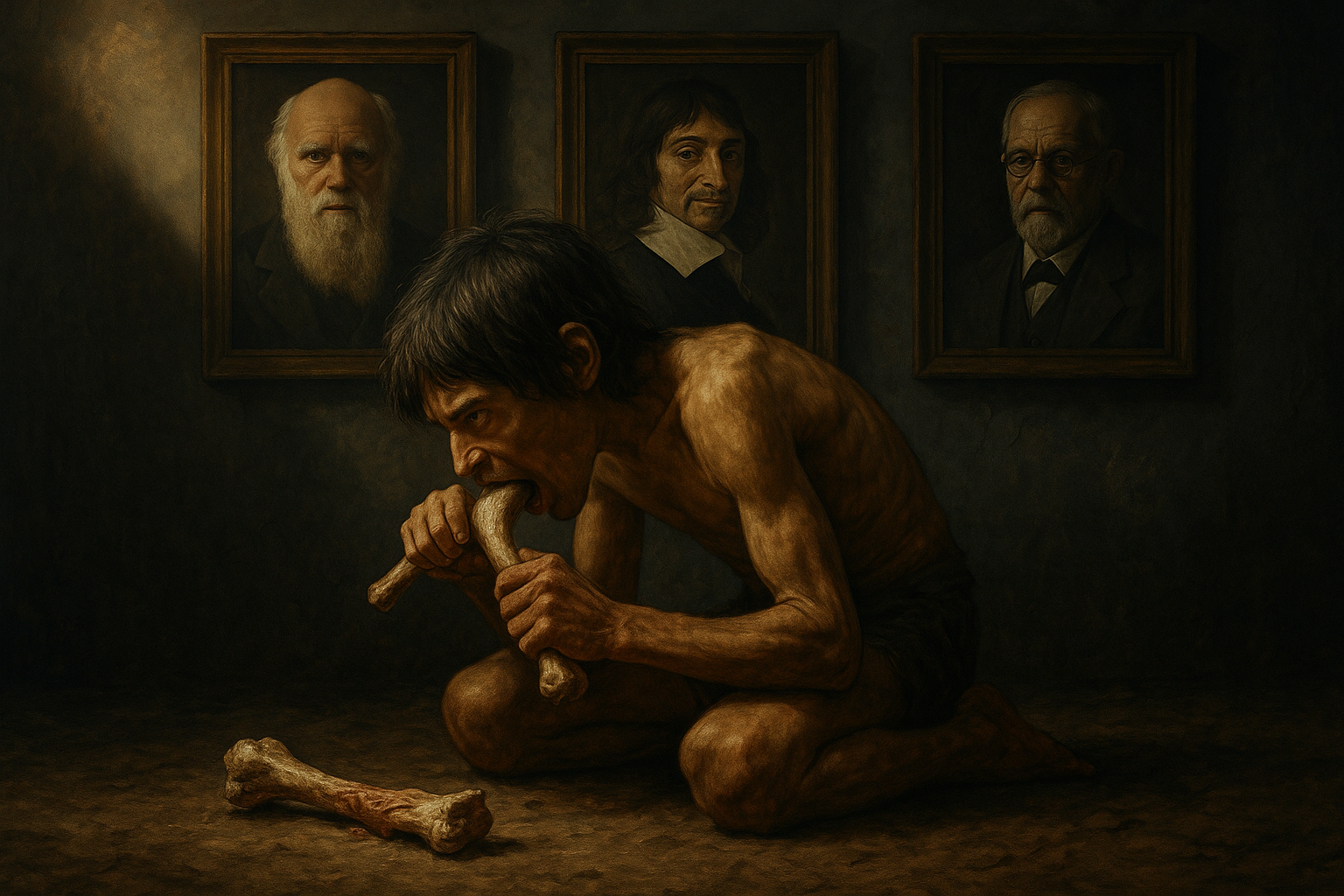

5. He preferred raw meat and bones to cooked food

Even after being taken in by the missionaries, Sanichar refused most human food. He snarled at cooked meals and only showed interest when given raw meat, which he tore at with his teeth. Caretakers were horrified when he gnawed on animal bones, cracking them open for marrow just as a wild predator might. While others at the orphanage adapted quickly to communal meals and utensils, Sanichar ate alone by hand, crouched low, and always with suspicion.

This wasn’t mimicry. It was instinct. Having likely scavenged and hunted to survive, Sanichar’s gut and preferences had adapted to a wolf’s diet. Over time, he accepted slightly cooked food, but never fully embraced human cuisine or table manners. Even decades later, accounts mention that his meals remained stripped-down and primal, echoing his early life. His taste for the wild wasn’t a phase, it was a permanent marker of where he’d come from. Source: Rare Historical Photos

6. He may not have been the only “wolf child” in India

Dina Sanichar wasn’t the only child reported to have been raised by wolves in colonial India. Between the 17th and 19th centuries, British and Indian authorities documented at least a dozen similar cases mostly in Uttar Pradesh and nearby regions. In many of these reports, locals described seeing naked children running with wolves or being discovered in dens alongside cubs. One account from 1843 described a boy who howled at night and attacked livestock. Another, from 1850, involved two girls found in Midnapore who growled, bit, and refused human contact for years.

Historians now believe some of these children were likely abandoned due to disabilities or poverty, then taken in or at least tolerated by animals. Wolves, known to be fiercely territorial, are unlikely to raise human young, but they may not have perceived lone children as threats. These cases likely represent complex blends of survival, trauma, and misinterpretation. Still, the sheer number of reports gave rise to the enduring myth of the Indian wolf child that captivated the world long before Sanichar’s story surfaced. Source: Tampa Bay Times

7. The orphanage thought he was possessed by evil spirits

When Sanichar was first brought to the Sekandra Mission Orphanage, many caregivers didn’t see a feral child; they saw a spiritual threat. His guttural growls, violent reactions to light, and wild eyes led some to believe he was possessed by demons or cursed by the forest. Staff reportedly performed prayers and attempted exorcisms, convinced that something unholy had taken root in him. Rather than compassion, his first encounters with human care were filtered through fear and superstition.

This reaction wasn’t unusual in the 19th century, when colonial and religious institutions often saw mental illness, trauma, or neurodivergence as signs of moral or supernatural failing. Sanichar’s behaviors, now understood as results of deprivation and trauma, were once seen as otherworldly. The orphanage’s mix of religious fervor and limited psychological knowledge shaped the way he was treated, with more effort placed on “saving” his soul than understanding his mind. Source: All That’s Interesting

8. He bonded more with animals than with people

Despite decades spent among humans, Sanichar never formed close relationships with other children or adults at the orphanage. But he did create a quiet, lasting bond with the orphanage’s pet dog. Witnesses described how Sanichar would sit beside the animal for hours, seemingly calm for the first time. He mimicked the dog’s posture and sounds and slept curled beside it. The connection, while primitive, was also profound; it was one of the few times Sanichar showed consistent trust and attachment.

Psychologists now recognize that early socialization heavily shapes a child’s ability to form emotional bonds. Sanichar, who likely missed those formative attachments in infancy, struggled to connect with people. But his comfort with animals suggested that he had experienced companionship, just not in human form. His preference for creatures over caretakers wasn’t rebellion; it was familiarity. For Sanichar, animals weren’t a reminder of what he lacked. They were the only family he had ever known. Source: The Archaeologist

9. He may have had developmental disabilities before he was found

Modern experts believe that Dina Sanichar’s behavior might not have come solely from being raised in the wild. Some neurologists and psychologists suspect he may have been born with developmental delays or conditions like autism, which could explain why he was abandoned in the first place. In 19th-century India, children with disabilities were often viewed as burdens or curses, and tragically, some were left to fend for themselves. If Sanichar had already been nonverbal or atypical before his time in the jungle, his behavior would have only intensified in isolation.

This theory reframes Sanichar’s story from a dramatic survival tale to one of societal failure. A child with unique needs may have been cast out, survived only through sheer instinct, and then further misunderstood by those trying to “fix” him. It also helps explain why, even after years of care, he never gained language or integrated socially. The wildness wasn’t just from the forest; it may have been how he first experienced the world. Source: Syfy

10. He died of tuberculosis—never having spoken a word

After more than 20 years at the Sekandra Orphanage, Sanichar died in 1895 from tuberculosis, a common and deadly disease in crowded institutions of the time. Despite being surrounded by caretakers and other children, he remained largely alone until the end. He never spoke, wrote, or crossed the invisible threshold into human society. His body was buried in the orphanage cemetery, no family, no legacy, just a name carved on a stone and a story passed through whispers and newspaper clippings.

Sanichar’s life was a haunting blend of human resilience and irreversible loss. Though his caregivers tried to teach him language, religion, and etiquette, he was a reminder that not all humans can be “civilized” in the ways society expects, especially after crucial years of development are lost. In a final twist of irony, it was not the dangers of the jungle that killed him, but the diseases of the so-called civilized world. Source: Literature Stack Exchange

11. His story challenged everything scientists thought about human nature

Dina Sanichar’s case rocked early debates about what makes us human. Could someone survive without society? Is language innate or learned? Sanichar became a living experiment, though not by choice, in what happened when a child grew up without language, education, or culture. Some scientists believed his brain had been “reset” by the wilderness. Others saw him as evidence that humanity is not automatic; it must be nurtured. Philosophers, linguists, and psychologists all weighed in, using his story as a lens to explore nature versus nurture.

He also sparked debates about animal intelligence and emotional capacity. If a pack of wolves had truly tolerated, or even raised, him, what did that say about interspecies relationships? Could animals show empathy to a lost child? While skeptics dismissed parts of his story as myth, Sanichar’s existence was well-documented. His life and the blank slate it seemed to represent remained a chilling and fascinating case study in how deeply we rely on connection to become fully human. Source: BBC

12. Similar cases have occurred all over the world

Dina Sanichar’s story isn’t unique; cases of so-called “feral children” have been documented in France, Ukraine, Uganda, and beyond. One of the most famous involved Victor of Aveyron, a boy found in the French woods in 1800 who couldn’t speak and was believed to have lived alone for years. Like Sanichar, Victor resisted social norms, preferred solitude, and never fully learned language despite intense instruction. In Uganda, a girl named Sujit Kumar was found living with monkeys. In Ukraine, Oxana Malaya reportedly lived among dogs after her parents abandoned her at age three.

These stories differ in detail but share haunting patterns: extreme neglect, lost language, and animal-like behavior. Modern experts caution that not all these cases involve animals raising the child; some are the result of prolonged isolation or abuse. But together, they reveal just how much of our “humanity” depends on nurture. Without touch, language, and bonding in early life, even a healthy brain can drift into unfamiliar territory that mirrors the wild. Source: Factual America

13. Some experts believe wolves didn’t raise him—but didn’t kill him either

While early reports painted a dramatic image of Sanichar being suckled and protected by wolves, many modern researchers believe a more plausible version: the wolves may not have raised him in the maternal sense, but they may have allowed him to co-exist nearby. Wild animals occasionally tolerate other species, especially young ones that don’t pose a threat or compete for food. It’s possible Sanichar survived by mimicking their movements, eating their scraps, and learning to approach without provoking aggression. He may have stayed close to the pack without truly being a part of it.

This interpretation doesn’t lessen the strangeness of his survival. If anything, it highlights the remarkable adaptability of children under extreme stress. A boy left alone in the forest, likely very young, found a way to live among predators without being devoured. Instead of being rescued in the traditional sense, he may have rescued himself by observing, mimicking, and gradually blending into the rhythms of life in the jungle. His wildness wasn’t gifted to him by wolves. He earned it through sheer instinct and silence. Source: The Guardian

14. His life continues to shape how we define humanity

More than a century after his death, Dina Sanichar remains one of the most studied and debated cases in the history of human development. His story is still used in psychology, linguistics, and anthropology to explore how much of who we are is shaped by environment rather than biology. Could a child without language ever become fully human in how we understand it? What happens when the brain doesn’t receive the input it needs to grow? Sanichar’s life didn’t answer these questions, making them impossible to ignore.

His existence also helped change how we care for abandoned or neglected children. Over time, societies began to understand the importance of early emotional and sensory development, and programs were created to support children who had been isolated or traumatized. In this way, Sanichar’s lonely journey wasn’t entirely in vain. Though he never spoke, never wrote, and never rejoined the world that left him behind, he left an imprint on science, care, and the fragile lines that define what it means to be human. Source: ArcGIS Storymaps