The Untamed Reality Of A Feral Legend

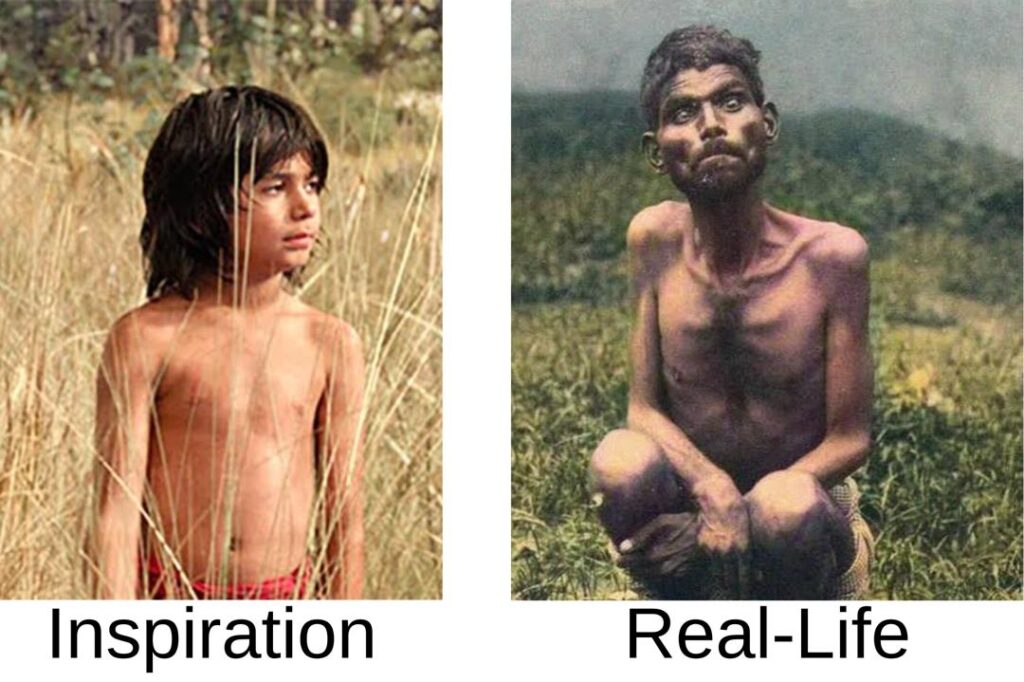

The story of a child raised by apex predators in the heart of the Indian wilderness sounds like the stuff of pure Victorian fantasy or a modern animated blockbuster. Most of us grew up with Rudyard Kipling’s Mowgli, a spirited boy who danced with bears and outsmarted tigers, yet the flesh-and-blood inspiration for this character lived a life that was significantly more sombre and complex. This topic matters because it challenges our fundamental understanding of what it means to be human while highlighting the incredible, if occasionally harsh, adaptability of the human spirit when it is stripped of civilisation and placed into the raw custody of nature.

Understanding the life of Dina Sanichar allows us to peer into a rare and haunting intersection of biology and environment where the lines between species begin to blur. His transition from the wolf dens of Uttar Pradesh to the structured confines of a mission orphanage serves as a poignant case study in developmental psychology and the lasting impact of early animal bonding. By exploring his reality, we move beyond the whimsical songs of cinema to respect a legacy defined by survival, the limits of human language, and the profound, unspoken connections that can exist between man and the wild.

Discovery Within A Wolf Den

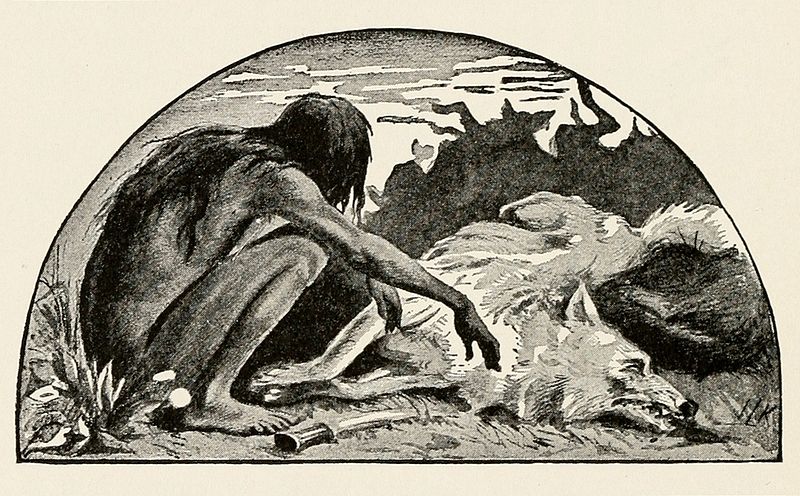

In the sweltering heat of 1867, a group of hunters traversing the Bulandshahr district in India stumbled upon a sight that defied all conventional logic. They were tracking a lone wolf into a deep cave when they noticed a small, spindly figure huddled amongst the cubs, moving with the same predatory grace as its lupine companions. Rather than a lost child crying for help, they found a boy who snarled at their approach and sought refuge in the shadows of the den. The hunters eventually smoked the wolves out of the cave to capture the child, who was roughly six years old at the time and completely assimilated into the pack’s social structure.

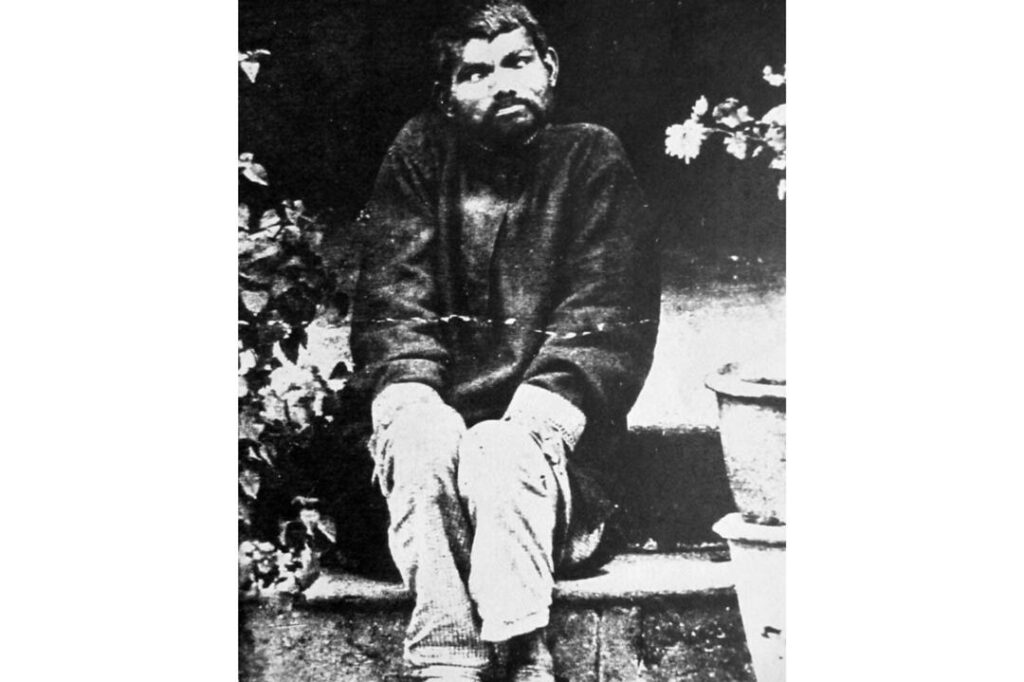

Upon his capture, the boy was sent to the Secundra Orphanage in Agra, where he was given the name Dina Sanichar, which translates to ‘Saturday’ in Hindi to mark the day of his arrival. His physical state was a testament to his years in the wild, as he possessed calloused skin and a skeletal structure adapted for constant quadrupedal movement. While the missionaries hoped to “civilise” him, they quickly realised that his bond with the wolves was not merely a phase of survival but a core part of his identity. This initial discovery sparked international intrigue, as Victorian society grappled with the uncomfortable reality of a human who had seemingly rejected humanity in favour of the wild.

Living As A True Lupine

Dina did not simply reside near the wolves; he lived as a functional member of their pack by adopting every nuance of their behaviour to ensure his survival. He moved exclusively on all fours, using his hands and feet as paws, which resulted in thick, protective layers of skin on his palms and knees. Unlike the fictional Mowgli, who stood tall and spoke to the trees, Dina was entirely non-verbal and relied on guttural snarls and high-pitched howls to express his emotions or needs. His instincts were finely tuned to the rhythms of the forest, meaning he remained perpetually alert to sounds and scents that were completely undetectable to the people who were now tasked with his care.

This total immersion in animal life meant that he initially found human comforts like beds or chairs to be confusing and even frightening. He would often attempt to hide in dark corners or under furniture, seeking the familiar security of a den-like environment. The caregivers at the orphanage observed that his social cues were entirely animalistic, as he showed affection through nuzzling and aggression through baring his teeth. It was a stark and sobering reminder that the “noble savage” trope of literature was a far cry from the reality of a feral child, whose very essence had been rewritten by the cold, hard requirements of staying alive in a world governed by teeth and claws.

Rejection Of All Cooked Food

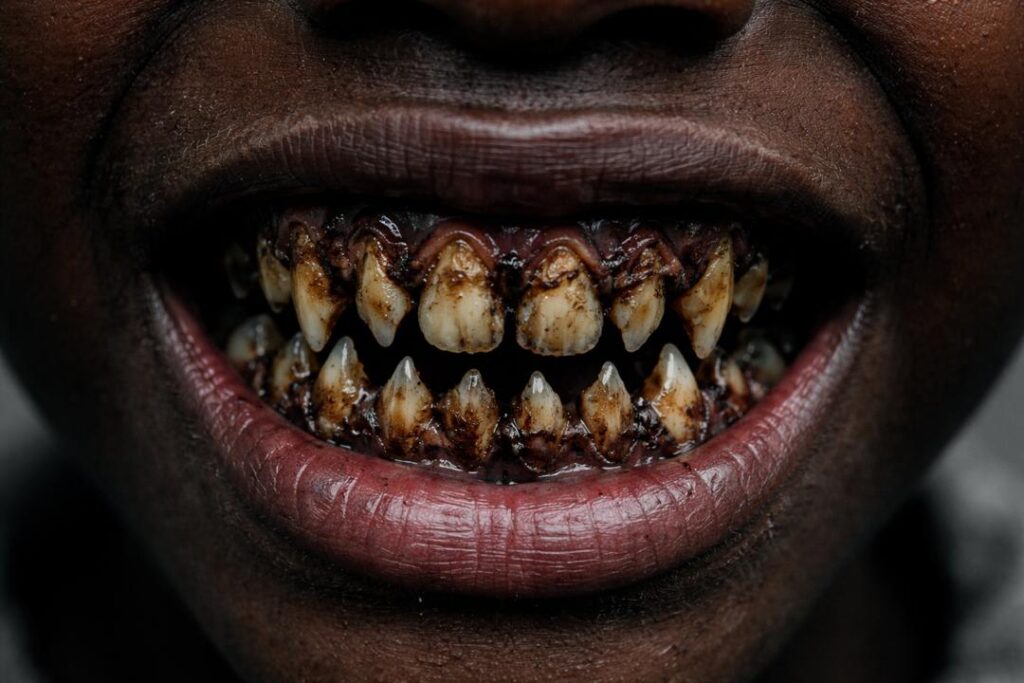

One of the most significant hurdles the orphanage staff faced was Dina’s absolute refusal to consume anything that had been prepared over a fire. For the first several months of his captivity, he turned his nose up at bread, vegetables, and cooked grains, showing a visceral disgust for the smells of human kitchens. He was driven by a biological craving for the diet he had known in the jungle, which consisted entirely of raw meat and bones. Witnessing him tear into animal carcasses with his bare hands and teeth was a jarring experience for the Victorian onlookers, yet it was the only way he knew how to nourish his body effectively.

To prevent him from starving, his caretakers eventually had to allow him access to raw meat, though they slowly tried to introduce other textures over several years. He was known to bury food in the dirt if he wasn’t hungry, mimicking the caching behaviour of wolves who hide their kills from scavengers. This dietary struggle highlighted the deep physiological changes that occur when a human is raised outside the norms of their species, as his digestive system and taste buds were calibrated for a predator’s lifestyle. It took nearly a decade for him to accept cooked food with any regularity, and even then, he never quite lost his preference for the primal satisfaction of a raw, bloody meal.

Silence Of The Jungle Child

While the Mowgli we see on screen is famous for his witty banter and songs, the real-life Dina Sanichar remained trapped in a world of absolute silence. Despite nearly twenty years of living among humans at the mission, he never mastered the art of speech or learned to communicate using a formal language system. His vocal cords and the language-processing centres of his brain had passed their critical developmental windows while he was in the jungle, leaving him unable to grasp the complexities of syntax or vocabulary. He could understand simple commands through tone and gesture, but his primary mode of expression remained the primal sounds of his former wolf family.

This inability to speak made Dina a deeply isolated figure within the orphanage, as he could never truly share his thoughts, memories, or feelings with those around him. He lived in a perpetual state of “otherness,” caught between a human form and a wolf’s mind, which led many visitors to view him more as a biological curiosity than a person. His silence was perhaps the most tragic aspect of his story because it meant that the secrets of his years in the wild died with him. He was a man who had seen the world through the eyes of a wolf, yet he lacked the human tools to ever tell the tale of what he had witnessed in the shadows.

Physiology Of A Wild Hunter

The physical transformation Dina underwent during his years in the wild was so profound that it altered his very appearance to resemble a woodland predator. His teeth were particularly striking, as they had become worn down and sharpened into jagged points from years of gnawing on tough hides and crushing bones. This gave his face a permanent, fierce expression that often unnerved those who attempted to provide him with medical care or clothing. His jaw muscles were exceptionally well-developed, and he possessed a biting force that was far superior to that of an average human, a necessary adaptation for someone who lacked tools and relied on their mouth to process food.

Furthermore, his body was covered in scars from the brambles of the jungle and the rough-and-tumble play of his wolf siblings, which acted as a permanent map of his survival. His sense of smell was reported to be incredibly acute, as he would often sniff the air to identify people approaching from a distance before he could even see them. These physical traits served as a constant reminder that he was a product of his environment, a biological bridge between two worlds that refused to fully reintegrate into civilised society. He walked with a distinctive, loping gait even when he was forced to stand upright, as his muscles were permanently conditioned for the explosive speed of a four-legged hunter.

Protection From The Wolf Pack

One of the most moving yet chilling aspects of Dina’s history is the fierce loyalty displayed by his adoptive wolf family at the moment of his capture. When the hunters first approached the den, the wolves did not flee in terror as many expected; instead, they stood their ground and bared their teeth to protect the human boy they viewed as their own. Reports from the time suggest that the hunters had to use fire and significant force to separate the child from the pack, as the wolves were willing to risk their lives to defend him. This bond suggests a level of inter-species social structure that goes far beyond simple proximity or convenience.

For Dina, this was the only family he had ever known, and the trauma of being forcibly removed from his protectors likely contributed to his lifelong difficulty in forming human attachments. To him, the hunters were not rescuers but violent intruders who had snatched him away from the security of his home. This event raises profound ethical questions about the nature of “rescue” and whether it was truly in the boy’s best interest to be taken from a family that loved and sustained him. While the humans saw a child in need of saving, the wolves saw a brother being kidnapped, and that tension between two different definitions of family haunted Dina until his final days.

Struggle To Adapt To Society

Life at the Secundra Orphanage was a constant uphill battle for Dina, who found the basic requirements of human civilisation to be an unbearable burden. He famously loathed wearing clothes, and his caretakers often found him shredding his garments or casting them aside the moment he was left alone. The sensation of fabric against his skin was likely overstimulating and restrictive for someone used to the freedom of the forest. Furthermore, he struggled with the concept of personal space and social boundaries, as he did not understand the intricate rules that govern human interaction and often reacted with confusion or hostility to being touched or crowded.

Despite the best efforts of the missionaries to integrate him into the daily routines of the orphanage, Dina remained a permanent outsider who preferred the company of animals to that of his peers. He did eventually form a close bond with another feral child who was brought to the facility later, and the two were often seen communicating through barks and grunts. This singular friendship suggested that while he couldn’t connect with “civilised” humans, he still possessed a deep-seated need for companionship with those who understood his unique trauma. His journey was a living testament to the idea that some spirits are so deeply shaped by the wild that they can never truly be tamed or made to fit into a traditional home.

Acute Senses And Survival Instincts

Dina’s time in the jungle gifted him with a suite of superhuman-like senses that allowed him to perceive the world in a way that modern humans have long since lost. He was capable of navigating in near-total darkness with ease, likely relying on a combination of heightened peripheral vision and a keen sense of spatial awareness. His hearing was so sensitive that the bustling noises of the orphanage often overwhelmed him, leading him to seek out quiet, secluded areas where he could rest. These traits were not magical, but rather the result of extreme biological necessity, as any lapse in attention in the wild would have meant immediate death.

Observers noted that his reflexes were lightning-fast, and he could catch small animals or insects with a single, fluid motion of his hand. This heightened state of awareness meant that he was always in a “fight or flight” mode, which made it difficult for him to relax in a human environment. While his caregivers saw these abilities as strange or primitive, they were actually the peak of human performance in a natural setting. Dina’s life demonstrated that the human body is capable of incredible feats of perception when it is forced to compete with the sharpest predators in the animal kingdom, proving that we are far more capable than our comfortable lives suggest.

Inspiration For The Jungle Book

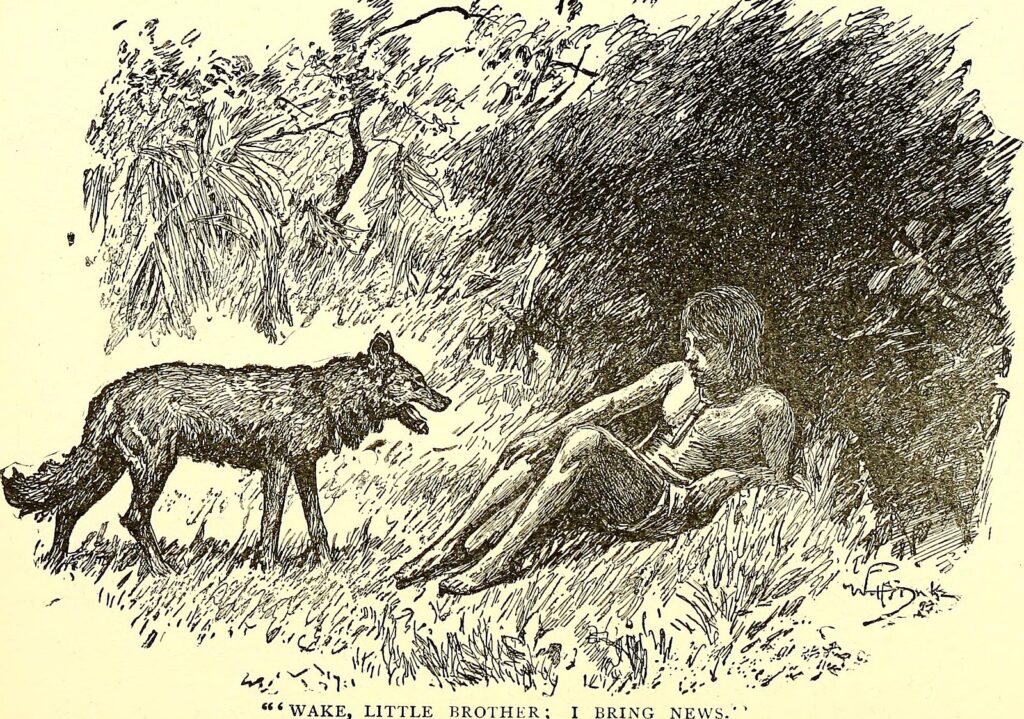

It is widely believed among historians and literary scholars that Dina Sanichar’s extraordinary life served as the primary catalyst for Rudyard Kipling’s world-famous stories. Kipling was living in India during the late 19th century when accounts of Dina’s capture and his subsequent life in Agra were circulating through the local press and colonial circles. While Kipling took immense creative liberties by giving Mowgli a voice and a cast of charming animal mentors, the core concept of a boy raised in a wolf den was undeniably drawn from the real-world reports of feral children like Dina. This connection bridges the gap between a tragic reality and a beloved piece of global literature.

However, the contrast between the two stories is stark, as Mowgli represents a romanticised vision of nature where man is the rightful master of the jungle. In reality, Dina’s life was far more difficult, marked by social isolation, physical deformity, and a complete lack of agency. By examining the link between the two, we can see how society often takes a painful truth and polishes it into a fable to make it more digestible. Dina’s legacy lives on through Mowgli, but it is important to remember the real boy behind the myth, a child who didn’t sing with bears but struggled every single day to reconcile his human heart with his wolf-like soul.

A Lone And Tragic End

Dina Sanichar’s life came to a premature and lonely conclusion in 1895 when he passed away from tuberculosis at the age of approximately thirty-five. His health had always been somewhat fragile due to the extreme conditions of his early childhood and the high stress of his forced transition into human society. He spent his final years as a quiet, somewhat forgotten figure at the mission, never having achieved the “civilisation” his captors so desperately sought for him. His death was a quiet affair, a far cry from the grand adventures one might expect for the inspiration of a legendary hero, and he was buried in a simple grave that reflected his humble and troubled existence.

The tragedy of his end lies in the fact that he was a man without a country, belonging neither to the world of wolves nor the world of men. He had been “saved” from the jungle only to spend the rest of his life as a curiosity, a living museum exhibit of what happens when nature wins the battle for a human mind. His story serves as a cautionary tale about the complexities of intervention and the reality that some wounds, especially those involving the loss of one’s fundamental identity, can never truly be healed. Even in his final moments, it is said he remained a man of few words, perhaps still dreaming of the moonlight and the pack he left behind.

The Shadow Of The Wild

The transition from a feral existence to a structured society is rarely the triumphant homecoming depicted in literature, as Dina Sanichar’s later years proved with heartbreaking clarity. While he was eventually taught to perform minor tasks and follow a basic schedule, the essence of the wolf never truly departed from his psyche, leaving him in a perpetual state of longing for a wilderness he could no longer reach. This internal conflict highlights the immense difficulty of reprogramming the human brain once it has fully committed to an animalistic survival mode during the most formative years of development and growth.

His story is a vital reminder that “rescue” is a relative term that often carries a heavy price for the individual being saved from their natural environment. To the missionaries, they were saving a soul from the darkness of the woods, but to Dina, they were perhaps removing him from the only place where he felt empowered and complete. By looking at the final stages of his life, we see a man who was physically present in the human world but emotionally anchored to the forest, a living ghost haunting the halls of the mission while his heart remained with the pack that first gave him a home.

The Addictive Nature Of Tobacco

One of the most baffling and peculiar developments in Dina’s life at the orphanage was his sudden and intense addiction to tobacco. Despite his general rejection of human habits and his inability to grasp the complexities of social etiquette, he took to smoking with a fervour that surprised all his caretakers. It became one of the few human activities he actually enjoyed, and he would often be seen with a pipe or a cigarette, puffing away in silence while staring out at the horizon. This habit was perhaps his only real coping mechanism for the immense stress of living in a world that he could not understand and that did not understand him in return.

Tragically, this addiction likely contributed to the respiratory issues that eventually led to his death from tuberculosis at such a relatively young age. Some historians suggest that the missionaries may have encouraged the habit as a way to keep him calm or to provide a rare bridge of shared activity between him and the staff. It remains a strange, humanising detail in an otherwise animalistic life, showing that even a boy raised by wolves could succumb to the vices of the civilisation that claimed to be civilising him. The image of the “wolf boy” quietly smoking a pipe is a poignant symbol of his fractured identity and the strange compromises he had to make to survive among men.

Better Treatment Among Animals

When we look back at Dina’s history, a disturbing pattern emerges where the wolves he lived with showed a higher level of social acceptance than the humans who supposedly rescued him. In the wolf pack, Dina was a functional member with a specific role, protected by his siblings and fed by the elders as part of a cohesive unit that valued his presence. In contrast, the human world treated him as a freak of nature or a scientific specimen to be poked, prodded, and studied by curious officials and bewildered doctors. He was never truly integrated into the social fabric of the mission as an equal, but rather lived on the fringes as a permanent ward.

This disparity raises a stinging critique of human society and our tendency to judge anyone who does not fit our narrow definitions of “normal” or “civilised.” The wolves did not care that he could not speak or that he walked differently; they only cared that he was part of the pack and contributed to their collective survival. Humans, burdened by ego and social hierarchy, could never see past his feral exterior to the person beneath, making his life in “civilisation” significantly lonelier than his life in the wild. His story suggests that true compassion is not found in teaching someone to wear clothes or eat with a fork, but in accepting them exactly as they are.

An Untamed Spirit To The End

Despite decades of exposure to human culture, Dina Sanichar remained fundamentally untamed until the moment he took his final breath. He never developed a sense of shame about his nakedness or his animalistic habits, and he continued to prefer the cold floor to a soft mattress whenever the opportunity arose. His caregivers noted that he seemed to possess a hidden internal clock that was synced with the moon and the seasons rather than the clocks on the wall. He was a man who lived in a state of constant, quiet rebellion against the constraints of walls and roofs, proving that nature’s imprint is often far deeper than the thin veneer of nurture.

His refusal to conform was not an act of spite but a biological reality, as his mind simply lacked the architecture to house the concepts of human social structure. This lifelong wildness made him a figure of both fascination and frustration for those who wanted to see him “cured” of his wolf-like tendencies. Dina’s life stands as a powerful testament to the idea that some parts of the human experience are written in the earth and the wind, and no amount of human intervention can erase the bond between a child and the wilderness that raised him. He died as he lived, a wolf in a man’s skin, forever listening for a howl that never came.

A Haunting And Lasting Legacy

The legacy of Dina Sanichar is one that continues to haunt our collective imagination, serving as the dark, realistic shadow behind every “feral child” story told today. He is the most well-documented case of a human being successfully integrated into an animal society, providing a rare and unfiltered look at the limits of human adaptability. His life reminds us that the stories we tell ourselves about the wild are often sanitised versions of a much harsher reality where survival is the only currency that matters. While he inspired a literary masterpiece, his own life was a series of struggles that highlighted the profound isolation of being caught between two different worlds.

Today, his story is studied by psychologists and historians who seek to understand the “critical period” of human development and the vital importance of early social bonding. Dina remains a symbol of the thin line that separates humanity from the animal kingdom, a line that he crossed and could never quite find his way back over. His existence challenges us to be more empathetic toward those who are different and to respect the powerful, mysterious forces of nature that can claim a human life as its own. He was the real Mowgli, but his jungle had no songs, only the silent, enduring strength of a boy who refused to forget the pack that loved him first.

The tragic life of Dina Sanichar teaches us that while the human spirit is remarkably resilient, it is also deeply fragile when severed from the social structures it was meant to inhabit. His story forces us to reconsider the ethics of imposing our own definitions of “home” and “happiness” on those whose lives have been shaped by a completely different set of rules.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.