1. Sphinx Cats – Not truly hairless or Egyptian

These unique cats aren’t truly hairless, they have a fine layer of fuzz that you can feel if you look closely. The breed was actually developed in Canada in the 1960s, not Egypt, thanks to breeders in Toronto who recognized this unusual trait and began breeding hairless kittens like “Prune” into a distinct line. Despite their bald appearance, Sphynx cats are covered in soft down and often described as having peach‑fuzz skin. They require extra care, regular bathing, sun protection, and gentle handling, to stay healthy and clean.

2. Chihuahuas – Origin mystery beyond Mexico

Though closely associated with Mexico, Chihuahuas may trace their roots to ancient Asia or even Egypt. DNA evidence shows much of their lineage stems from Old‑World toy dogs, with only a small portion of their ancestry linked to pre‑Columbian “Techichi” dogs of Mexico. For example, a 2013 study suggested that Chihuahuas retain about 4 % DNA from native dogs, hinting they were crossed or replaced by European breeds brought over centuries ago. This blend of continents gave rise to the tiny companion we know today.

3. Guinea Pigs – Neither pigs nor from Guinea

Guinea pigs aren’t pigs at all but rather squeaky little rodents native to the Andes, not the country Guinea. The name was likely adopted by European traders and simply stuck, despite being misleading.These tiny animals thrive in mountainous regions of South America and have been domesticated for centuries, not for their meat in Europe, but rather as beloved pets and study subjects due to their gentle nature and curious squeals.

4. King Cobras – More king than cobra

Though called “King Cobra,” this snake doesn’t belong to the same genus as true cobras. It stands alone in its own genus, Ophiophagus, and diverged significantly from the familiar Naja cobras millions of years ago. As the world’s longest venomous snake, King Cobras possess their own unique biology, behavior, and evolutionary history, despite what their crown‑bearing name implies.

5. Koala Bears – Marsupials, not bears

Koalas aren’t bears at all, but marsupials, more closely related to wombats than any bear species. Unlike placental mammals, koalas carry their young in a pouch after birth.These eucalyptus‑eating tree dwellers are native to Australia and have evolved a specialized diet and digestive system, quite unlike the omnivorous tendencies of true bears.

6. Electric Eels – Not eels, but knifefish

Though their name suggests otherwise, electric eels belong to the knifefish group (Gymnotiformes), not true eels (Anguilliformes). These fascinating creatures share closer ancestry with catfish and carp, as confirmed by taxonomic studies showing they diverged long ago from eel-like species. Renowned for their incredible ability to generate powerful electric shocks, up to 860 V, electric eels use low-voltage pulses to locate prey and high-voltage discharges to stun them. This dual electric system makes them a marvel of evolutionary adaptation, completely redefining our idea of what an “eel” can be.

7. Prairie Dogs – Ground squirrels, not canines

Despite their barking alarm calls, prairie dogs are rodents, specifically ground squirrels, not dogs. They live in vast communal burrows or “towns,” featuring complex networks that can span dozens of acres underground. These social animals have a fascinating communication system: their barks vary depending on predator type, and recent studies even show other species like birds eavesdrop on these calls for safety. With their intricate language and underground engineering, prairie dogs are far more like communal rodents than distant dog relatives.

8. Mountain Lions – Big cats, not lions

Mountain lions, also called cougars or pumas, aren’t true lions (which belong to Panthera). These big cats are more closely related to domestic cats and other smaller wildcats within the genus Puma. Unlike the social African lion, mountain lions are solitary and range across North and South America. They evolved in the Americas and adapted to diverse habitats, from forests to deserts, using stealthy hunting and tree-climbing skills more akin to house cats than to their roaring African cousins. Their name may evoke a regal image, but their genetics tell a different, more nuanced story.

9. Horned Toads – Lizards, not toads

Horned toads (aka horned lizards) aren’t amphibians, they’re reptiles, specifically lizards in the genus Phrynosoma. These stocky creatures are covered in spines and camouflaged skin. In a remarkable defense, some species can squirt blood from their eyes to deter predators. Living in deserts and scrublands of North and Central America, horned lizards rely on this autotomy to escape threats. Their diet mainly consists of ants and they blend so seamlessly with sandy ground that they often go unnoticed, except when they surprise you with their bizarre, blood-squirting trick.

10. Flying Lemurs – Gliders, not lemurs

Despite their name, flying lemurs aren’t lemurs and they don’t truly fly. Belonging to the order Dermoptera, these Southeast Asian mammals glide between trees using flaps of skin called patagia. Their cousin relationship to primates places them outside the true lemur group. They possess a gentle, nocturnal lifestyle, feeding on leaves and nectar high in forest canopies. Their silent, gliding movement lets them slip from tree to tree without a sound. So while “flying lemur” is catchy, it’s a misnomer that overlooks their unique biomechanics and evolutionary ties.

11. Fireflies – Glowing beetles, not flies

Fireflies, or lightning bugs, aren’t true flies at all; they’re soft-bodied beetles in the Lampyridae family. Their glowing abdomens, a magical light show at dusk, are produced through bioluminescence, used primarily for attracting mates and sometimes to deter predators. These beetles spend most of their lives as larvae in moist environments, feasting on snails, slugs, and other small creatures. Sadly, habitat loss, pesticides, and light pollution are threatening their populations across North America and beyond. Conservationists stress the need to reduce artificial light, delay lawn cleanups, and avoid chemicals to help preserve fireflies for future generations.

12. Sea Cows – Manatees related to elephants

Manatees, nicknamed “sea cows,” aren’t related to cattle, they’re aquatic mammals in the order Sirenia, closely related to elephants and dugongs. Their shared traits include continuous tooth replacement and features like similar skull structures. These gentle giants graze on seagrass in warm coastal waters and rivers, playing a vital role in marine ecosystems. At up to 4.6 meters long and 1 775 kg, manatees display elephant-like dental wear patterns, reinforcing their evolutionary bond.

13. Crayfish – Freshwater crustaceans, not fish

Crayfish, also called crawfish or crawdads, aren’t fish, but freshwater crustaceans related to lobsters, shrimp, and crabs. The term “crayfish” comes from Old French, influenced by folk etymology, despite these creatures living mostly in freshwater habitats. They’re ecologically important as omnivorous detritivores, feeding on dead plants, small animals, and algae in streams, swamps, and lakes. With over 625 species worldwide and more than 400 in North America alone, crayfish help shape aquatic environments, and are a culinary staple in places like Louisiana and Sweden.

14. Saber-Toothed Tigers – Not tigers at all

“Saber-toothed tigers” (like Smilodon) weren’t tigers or even in the genus Panthera. They belong to the extinct Machairodontinae subfamily, which diverged from modern big cats around 20 million years ago. These iconic prehistoric predators sported massive canines up to 20 cm long and lived during the Pleistocene in the Americas. Despite the misleading name, their skull, teeth structure, and evolutionary lineage distinguish them sharply from true tigers, lions, and their kin.

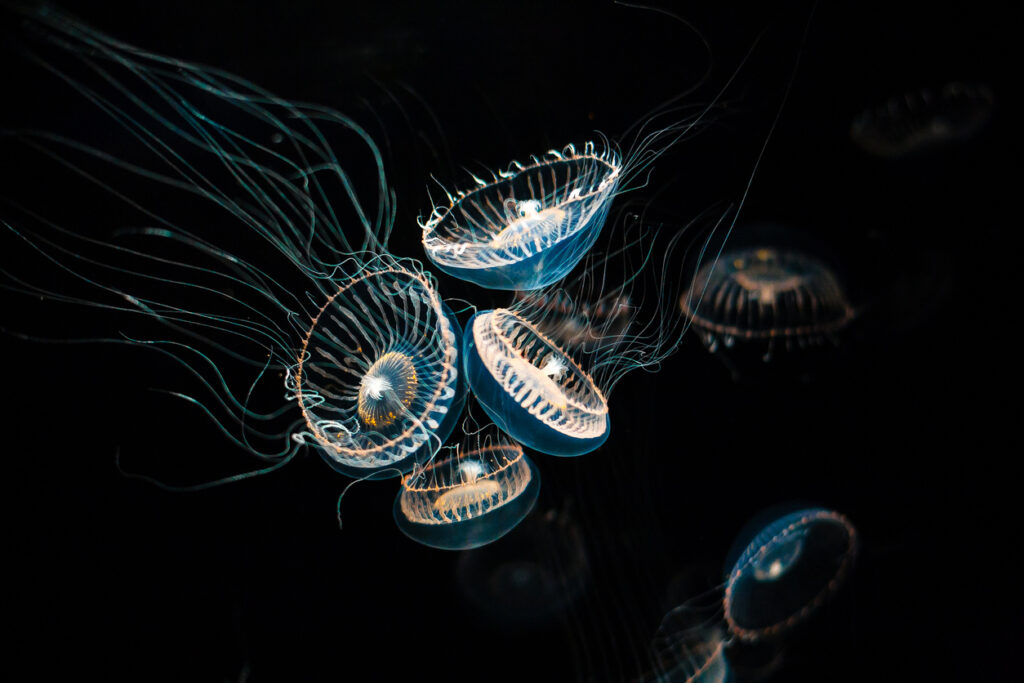

15. Jellyfish – Invertebrate drifters, not fish

Jellyfish, or “jellies”, are gelatinous invertebrates in the phylum Cnidaria, not fish. They lack bones, brains, hearts, or blood, and are over 95% water. They drift through oceans, sometimes carpeting coastlines in blooms. Their tentacles bear stinging cells called cnidocytes, used for capturing prey or defending themselves. Their simple, ancient body plan has persisted for hundreds of millions of years, long before modern fish or even dinosaurs appeared.

16. Flying Squirrels – Gliders, not flyers

These nocturnal creatures don’t truly fly, they glide. A flap of skin called the patagium stretches from wrist to ankle, acting like a parachute when they leap from trees. Some species can glide up to 150–500 feet, steering with their legs and bushy tail as they navigate the night sky. This silent gliding helps them evade ground predators and sneak through dense forest canopies. Their large eyes and super‑long whiskers are perfectly adapted for nighttime navigation. Interestingly, their graceful glides inspired modern wingsuits and flying drone research.

17. Jackrabbits – Hares, not rabbits

Jackrabbits are not rabbits, they’re hares in the genus Lepus. Unlike rabbits, hares are born fully furred with open eyes and can hop around soon after birth. They also build shallow forms instead of burrows, and remain larger, leaner, with longer legs and ears designed for speed and heat regulation. These swift mammals, some reaching speeds up to 40 mph, largely live solitary lives across open plains and deserts. Their remarkable self‑sufficiency from birth and rapid escaped lifestyle sharply contrast with the social, burrowing rabbits most people imagine.

18. Peacocks – Only the flashy males

We call the males peacocks and the females peahens, together they’re peafowl. Male peafowl carry extravagant trains of iridescent feathers, measuring up to 7 feet long, used in mating displays, while females sport more muted tones and build nests and raise chicks. Research shows that although peacocks’ many eyespots attract attention, peahens actually focus on the train’s width and shake during courtship. Together, these peacocks weave sexual selection, camouflage, and parenting roles into a fascinating tapestry of evolutionary strategy.

This story 18 Animals That Aren’t What They Seem was first published on Daily FETCH