1. The “Good Mother Lizard” Revealed

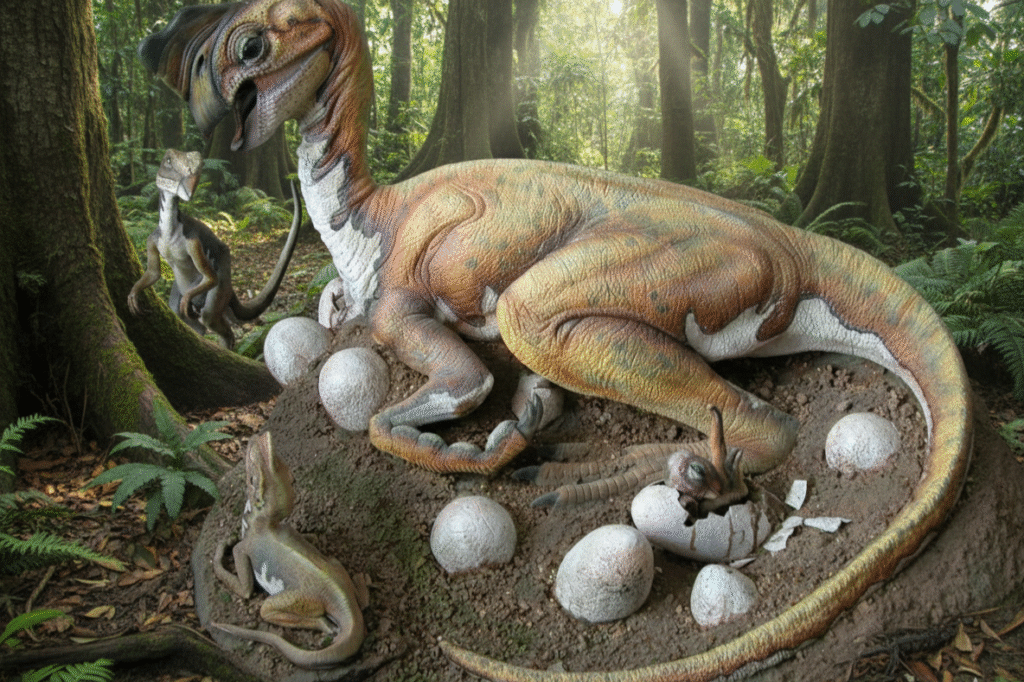

The duck-billed dinosaur Maiasaura peeblesorum earned its name, which translates to “good mother lizard,” thanks to a remarkable discovery at the “Egg Mountain” nesting site in Montana, USA. Palaeontologists found nests containing clutches of eggs, as well as the remains of hatchlings and juveniles. The young in these nests were too large to be newly hatched but too small to be independent, suggesting the adult Maiasaura provided post-hatching parental care by guarding and possibly feeding their young until they were large enough to leave the nest. This was one of the first strong pieces of evidence that non-avian dinosaurs nurtured their young.

2. Altricial vs. Precocial Young

Fossilized nests offer clues about the maturity of the young at hatching, which dictates the level of care required. Dinosaurs with altricial young, like Maiasaura, had hatchlings that were relatively helpless, requiring extended parental feeding and protection in the nest, similar to modern songbirds. In contrast, dinosaurs with precocial young, such as some sauropods or primitive ornithopods, produced hatchlings that were likely more developed, able to walk and forage almost immediately, requiring less direct parental investment after leaving the egg. The condition of the young’s leg bones and tooth wear provides key insights.

3. Proof of Paternal Incubation

The discovery of adult oviraptorids like Citipati and Oviraptor fossilized in a bird-like brooding posture over their nests initially led to the incorrect assumption of egg-stealing, but later proved they were attentive parents. Further analysis of the adult bones found in association with the clutches, specifically the lack of medullary bone (a calcium-rich tissue found only in egg-laying female birds), strongly suggests that the adults sitting on the nests were the males. This points to a pattern of paternal care, where the father incubated the eggs, a behavior seen in some modern birds like emus and ostriches.

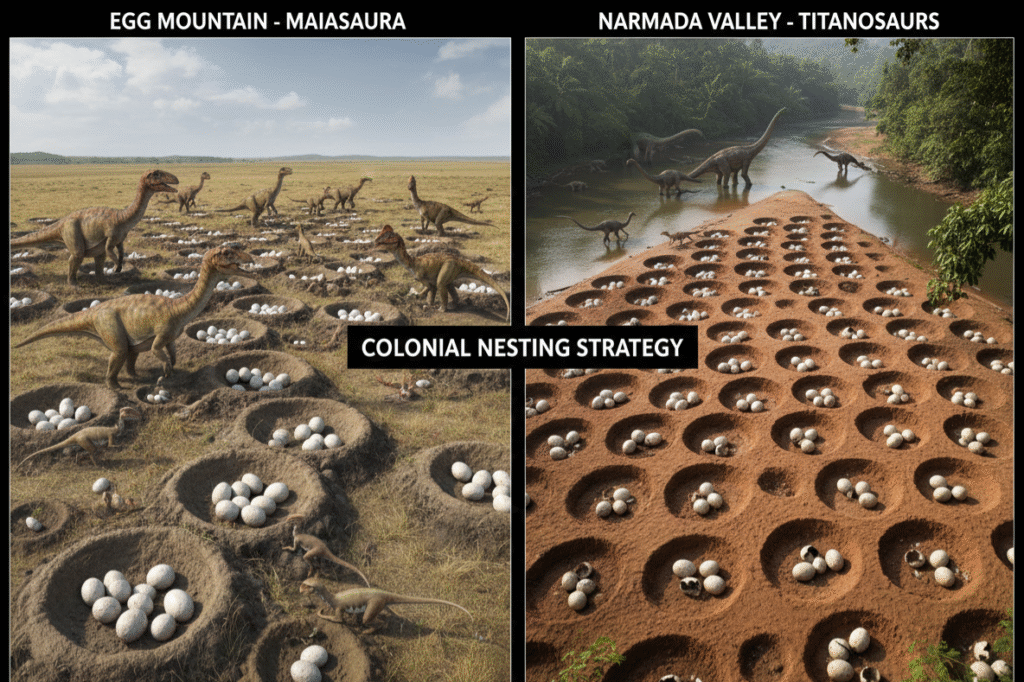

4. Nesting in Colonies for Safety

The sheer number of nests found clustered together at sites like Egg Mountain (Maiasaura) and the Narmada Valley in India (titanosaurs) reveals that some dinosaurs were colonial nesters. This communal nesting strategy, much like in modern seabirds or turtles, would have offered collective defense against predators, increasing the overall survival rate for the eggs and hatchlings. For the massive titanosaurs, the close spacing of their nests suggests that the adults did not linger after laying, reinforcing the idea that colonial nesting was primarily a strategy for safety in numbers during egg-laying.

5. Nests as Thermal Incubators

The structure of the fossilized nests indicates deliberate strategies for thermal regulation. Some nests were simple scrapes in the ground, while others were elaborate mounds of mud and vegetation. Large herbivorous dinosaurs like titanosaurs often buried their eggs in deep pits, relying on the heat generated by decaying plant matter or the surrounding soil to incubate their eggs, similar to modern crocodiles. This use of natural heat demonstrates an understanding of their environment to ensure the successful development of the embryos.

6. The Ring-Shaped Clutch Strategy

Many oviraptorosaur nests are found with the elongated eggs meticulously arranged in a tight ring pattern, sometimes stacked in two or three layers. This precise arrangement left a central, open space in the middle of the clutch. Palaeontologists hypothesize this ring-shaped layout allowed the brooding adult (likely the male) to sit squarely on the center of the nest, providing direct contact and insulation to the eggs without putting its full body weight on them, thus preventing crushing, a crucial adaptation for large dinosaurs.

7. Evidence of Soft-Shelled Eggs

Recent discoveries, particularly of eggs from basal sauropods like Protoceratops, show remnants of soft, leathery eggshells. Unlike the hard-shelled eggs of most modern birds and many other dinosaurs, soft-shelled eggs require burial in a moist, protected environment to prevent desiccation. This suggests that the earliest dinosaurs had more limited nesting habitats and may have employed a lower level of parental care, similar to modern turtles who bury their eggs and leave them.

8. Long-Term Nest Site Fidelity

The presence of multiple, superimposed nesting layers or repeated discoveries of nests at the same exact location over time suggests that some dinosaur species, such as Maiasaura, exhibited nest site fidelity. They returned to the same sheltered, advantageous areas year after year to lay their eggs. This implies a level of social learning or inherent knowledge passed down through generations about the best, safest locations for a successful clutch.

9. Tooth Wear in Hatchlings

One intriguing line of evidence for parental care comes from examining the teeth of Maiasaura hatchlings and juveniles found in the nesting sites. Their tiny teeth showed signs of wear, indicating they had been eating. However, they were still too small to have foraged outside the nest. This suggests the adult parents were actively bringing food back to the nest, potentially regurgitated plants or insects, to feed their semi-altricial young, solidifying the Maiasaura’s “good mother” reputation.

10. Embryos Reveal Developmental Stages

The rare discovery of fossilized embryos within intact eggs provides a direct “snapshot” of the development of the unborn dinosaur. By analyzing the skeletal structure and size of the embryo relative to the full egg, scientists can estimate the incubation period and the degree of bone development at the point of hatching. This data is critical for determining if a dinosaur was more altricial or precocial and how long a parent would have needed to protect the clutch.

11. Egg Porosity and Burial Depth

The shell of a dinosaur egg is not solid; it contains thousands of microscopic pores that allow the embryo to “breathe,” exchanging gases and water vapor with the external environment. Studies have shown that eggs intended for deep burial in the soil (like those of some sauropods) have a higher density of pores compared to eggs that were left partially exposed on the surface (like those of oviraptorosaurs). This variation in egg porosity is a direct reflection of the parent’s chosen nesting strategy.

12. Nest Structure and Egg Shape

Fossil evidence connects the shape of the egg to the design of the nest. The eggs of most dinosaurs, particularly those of the bird-like theropods, were asymmetrical and elongated, similar to modern bird eggs. This shape is often associated with eggs laid in partially open nests where the parent broods. In contrast, the eggs of sauropods were often spherical, a shape commonly found in eggs that are buried in the ground for incubation, as the round shape is structurally stronger for being piled or covered with soil.

13. Crèches and Juvenile Herds

Fossil beds containing large groupings of juvenile dinosaurs of the same species and similar age, sometimes a considerable distance from a main nesting site, are evidence of “crèche” or nursery behavior. For example, herds of juvenile Psittacosaurus or Maiasaura found together suggest that after hatching, the young were gathered into large groups, potentially watched over by one or a few non-breeding adults. This communal care provided protection and a social structure before they dispersed as independent adults.

14. Evidence of Food Near the Nest

By analyzing the size variation and bone histology of different-sized juveniles found together in a nest, scientists can estimate the growth rate of the hatchlings while they were under parental care. For Maiasaura, the nested young show a dramatic increase in size before leaving, suggesting the parental investment in feeding the young was significant, accelerating their growth and giving them a better chance of survival when they eventually left the nest.

15. The Evolution of Avian Behavior

Ultimately, the most profound message from fossilized dinosaur nests is that many of the complex parental behaviors we associate with modern birds, from brooding posture and nest structure to altricial young and paternal care, have deep evolutionary roots in their non-avian dinosaur ancestors, particularly theropods. The nests are a physical record of the slow, successful evolution of family life over millions of years.

Each fossilized nest is a preserved family album, revealing a rich history of parental strategies that continue to echo in the bird families of today. It reminds us that life’s most fundamental bonds are ancient.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.

This story What Fossilized Nests Tell Us About Dinosaur Parenting was first published on Daily FETCH