1. Glass Milk Bottles Delivered to Your Door

Before plastic jugs dominated the dairy aisle, the routine of glass milk bottle deliveries was a cornerstone of American life. Every morning, a milkman, an indispensable figure in the community, would navigate neighborhood routes, leaving fresh, cold bottles on the porch. Children often raced to retrieve them, eager for breakfast. This system was environmentally sustainable by design; families were expected to rinse the empty bottles and leave them out for the milkman to collect and reuse. The clinking of bottles was a familiar morning soundtrack. This entire logistical dance supported a hyper-local supply chain and a neighborly relationship with the dairy. However, as supermarkets expanded their cold storage capabilities in the 1960s and 1970s and plastic packaging became cheaper, the convenience of one-stop shopping gradually eroded the need for the milkman. By the 1980s, the widespread practice of home milk delivery, along with its reusable glass containers, had all but disappeared, becoming a nostalgic emblem of a different era.

2. Phone Booths on Every Corner

The phone booth was a vital piece of the 1950s infrastructure, acting as the public, portable link to communication before personal mobile phones existed. These small, often glass and metal, enclosures were ubiquitous, particularly in urban areas and near major roads, and typically featured a folding door to ensure privacy. The cost of a local call was a modest dime, making it essential for everyone to keep some change handy. The booth provided a crucial lifeline for emergency calls, last-minute plan changes, and staying in touch while away from home. Their distinctive glow at night often served as a welcoming beacon on a dark street. The technology within, a simple payphone, was the pinnacle of accessible public communication. However, the rise of the mobile phone, starting in the 1980s and becoming common by the late 1990s, rendered them obsolete. While some architectural shells remain, the fully functional, constantly utilized phone booth, the place to ‘put a dime in and make a call’, is now essentially extinct, surviving mostly as a nostalgic prop in movies.

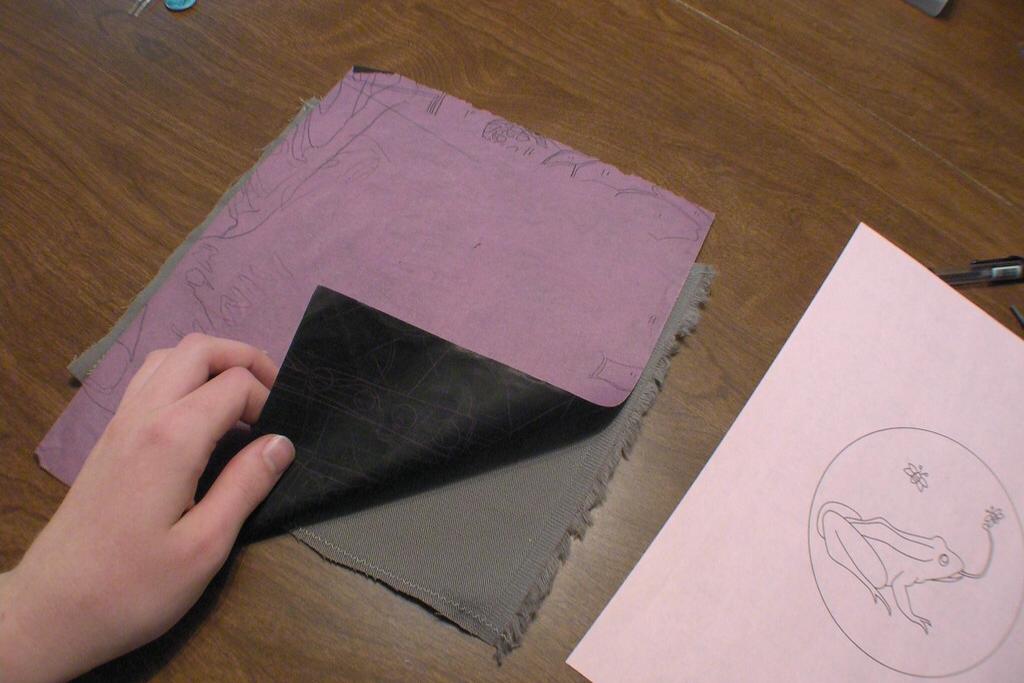

3. Carbon Paper for Copying

In the mid-20th century office, carbon paper was the non-negotiable technology for creating duplicate copies of documents. Before the widespread adoption of affordable photocopiers and digital printers, duplicating invoices, letters, or forms was a manual process. The setup involved sandwiching a sheet of this wax-coated paper, which was inked on one side, between the original document and the second sheet. When a typewriter key struck the top page, the impact transferred the ink from the carbon paper onto the sheet below, creating an instant copy. While revolutionary for its time, the process was notoriously messy; the black or blue carbon easily smudged onto hands, stained desks, and made documents prone to marks. Furthermore, even a slight misalignment or an errant pen stroke could ruin the entire batch of copies. Its slow, messy, but necessary function in the 1950s business world was completely eradicated by the perfection and efficiency of Xerox photocopiers and other electronic duplication methods, turning the once-essential carbon paper into a historical curio.

4. Wringer Washing Machines

The wringer washing machine represented a transitional period in home laundry, bridging the gap between purely manual washing and the fully automated machines that became common later in the 1950s. These machines featured a large tub for washing clothes and, crucially, a set of two rubber rollers (the wringer) mounted on top. After the wash cycle, the user had to manually feed each piece of heavy, water-soaked laundry through the turning rollers to squeeze out the excess water. This mechanical process, driven by a hand-crank or a low-power motor, required constant supervision. While a vast improvement over scrubbing clothes on a washboard, the wringer posed a significant safety hazard. Fingers, hair, or loose clothing could easily be caught and pulled into the rollers, making laundry day a potentially dangerous chore, especially for unsupervised children. The increasing affordability and safety of fully automatic washing machines in the 1960s, which performed the wash, rinse, and spin-dry cycles internally, permanently retired the wringer machine from the vast majority of American homes.

5. Tin TV Dinner Trays

The concept of the TV dinner, introduced by Swanson in 1953, fundamentally changed American dining habits and introduced the era of casual convenience. The original packaging was key: a segmented, rectangular aluminum or tin foil tray that held an entire meal, typically turkey, gravy, stuffing, and a side of vegetables, and served as both the cooking vessel and the plate. The tin was necessary because the meal was designed to be heated directly in a conventional oven, often for 30 to 45 minutes, allowing families to easily enjoy a hot meal with minimal cleanup. The success of the TV dinner was directly tied to the growing popularity of television in the home, normalizing the ritual of eating while watching shows, a major cultural shift. However, the introduction of the microwave oven in the 1970s and its widespread adoption in the 1980s spelled the end for the pure tin tray. Since metal cannot be used in a microwave, manufacturers switched to microwave-safe cardboard, plastic, and aluminum-lined trays, ensuring the quick and convenient meal could be ready in minutes, leaving the original oven-only tin tray to be remembered as a hallmark of 1950s kitchen innovation.

6. Rolodex Card Files

The Rolodex was the organizational backbone of the 1950s office and a powerful personal tool. Short for “rolling index,” this device consisted of a spinning rotor mounted on a base, which held dozens or hundreds of detachable paper cards used for storing contact information, notes, and crucial business details. Secretaries and businessmen relied on the tactile, mechanical act of quickly spinning the wheel to locate a contact’s name, phone number, or address. It represented the pinnacle of analog data retrieval, allowing for easy alphabetical filing and quick access. While simple, the Rolodex was an invaluable networking tool, symbolizing a person’s professional reach and network density. The term itself became a metaphor for a person’s contacts, often referred to as someone’s “personal Rolodex.” The advent of personal computers, dedicated contact management software, and especially the smartphone with its instant digital address book rendered the physical, spinning Rolodex obsolete. Although the digital successors perform the same function, the physical product and the ritual of flipping through a personalized, tangible index of contacts have vanished from the modern workplace.

7. Typewriter Erasers with Brush Ends

Before the arrival of correcting fluid or the digital “delete” key, the typewriter eraser was an absolutely essential tool for every typist. Because the mechanical strike of a typewriter key pressed ink firmly into the paper, simply using a soft, conventional pencil eraser would not suffice; it often led to smudging and left residue. Typewriter erasers were made of a harder, grittier abrasive material, often pink or gray rubber, designed to actually scrape or grind the ink off the paper’s surface. This process inevitably created a lot of tiny rubber and paper particles. To clean up this mess without smudging the surrounding text, the erasers came equipped with a small, stiff brush attached to one end. The brush was used to gently sweep away the debris. Despite the tool’s necessity, using it often led to a thin, worn spot on the paper or even a small hole if one was too vigorous. The arrival of self-correcting typewriters and later, word processing software and printers, completely eliminated the need for this abrasive and vital piece of 1950s office equipment.

8. Hand-Crank Ice Cream Makers

Making ice cream in the 1950s was a labor-intensive, celebratory family affair thanks to the popularity of the hand-crank ice cream maker. These devices typically consisted of a wooden bucket that housed a metal canister where the cream mixture was poured. The key to the process was surrounding the canister with a carefully measured mixture of rock salt and ice, which lowered the temperature below the freezing point of water, allowing the custard to freeze. The hand-crank on the lid had to be turned continuously and slowly to agitate the mixture, preventing the ice cream from forming large, unappetizing crystals. This repetitive action was often a job shared by children or taken on in shifts by adults; it was exhausting work that could last 30 minutes or more. The anticipation and the eventual rich, homemade reward made the effort worthwhile. However, the convenience of affordable electric ice cream makers and the massive increase in high-quality, inexpensive store-bought ice cream permanently sidelined the hand-crank model, turning a common kitchen appliance into a prized piece of nostalgic summer equipment.

9. Diaper Services with Cloth Deliveries

In the pre-disposable era of the 1950s, diaper services provided an essential, labor-saving solution for new parents. Before products like Pampers achieved mass market dominance in the mid-1960s, using cloth diapers was the standard, which meant an endless and unpleasant cycle of washing, soaking, and sanitizing them at home. Diaper services completely circumvented this grueling household chore. They operated via a weekly pickup and delivery system: a service truck would arrive, drop off a large, fresh supply of laundered, sanitized, and neatly folded cloth diapers, and simultaneously collect the week’s worth of soiled ones contained in a special can or bag. For a relatively small fee, this service offered a sanitary and convenient alternative to home washing. The cloth diapers were industrial-strength washed and sterilized, a process few homes could replicate. The rise of the disposable paper-based diaper in the late 1960s and 1970s, offering unparalleled convenience and zero required laundry, marked the quick and decisive end of the widespread, necessary, and once-ubiquitous diaper service model.

10. Drive-In Theater Car Speakers

The drive-in movie theater was a cultural centerpiece of the 1950s, serving as a popular destination for families and especially for teen dates. The unique technology that defined the drive-in experience was the individual metal speaker box. Instead of projecting sound through massive outdoor speakers, each car was equipped with its own dedicated sound source. Drivers or passengers would unhook the heavy, bulky speaker from the pole beside their parking spot and hang it directly over the car’s partially rolled-down window. The sound quality was often tinny, distorted, and prone to crackling, but it provided the necessary audio for the film. The ritual of placing the speaker was an integral part of the drive-in experience. As technology advanced, many drive-ins realized they could offer vastly superior, uniform sound by simply transmitting the movie’s audio via a low-power FM radio frequency that patrons could tune into on their car’s stereo. This innovation allowed for much clearer sound and eliminated the cumbersome, easily damaged physical speaker units, making the classic, window-hooked speaker a treasured artifact of vintage Americana.

11. Mercury Thermometers

For decades, the mercury-in-glass thermometer was the standard, highly reliable medical instrument found in every 1950s medicine cabinet. Its simple yet effective design relied on the principle of thermal expansion: a tiny column of silver-colored liquid mercury would rise in a glass tube, indicating the temperature with high precision. They were celebrated for their accuracy and durability, lasting for years if not dropped. However, the defining feature of these thermometers, the mercury itself, was also their fatal flaw. Mercury is a potent neurotoxin, and a broken thermometer could release this dangerous substance, posing a serious health and environmental hazard, especially to small children. The cleanup of a broken mercury thermometer was complex and dangerous. Growing awareness of these dangers led to a widespread global phase-out. By the early 2000s, government regulations and safety campaigns had successfully replaced them with safer, mercury-free alternatives, primarily digital thermometers, which offered instant, clear, and non-toxic temperature readings, relegating the glass mercury stick to the status of a dangerous but once-common household relic.

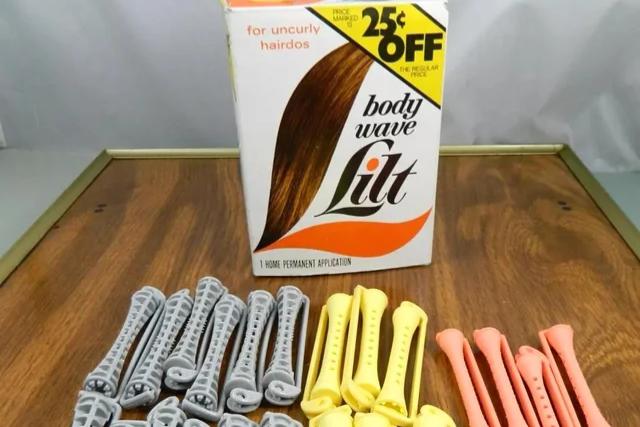

12. Permanent Wave Home Kits

The pursuit of the glamorous, often tightly-curled hairstyles popular in the 1950s fueled the market for permanent wave home kits. These DIY kits allowed women to save the cost of a beauty parlor visit by performing a chemical treatment at home to achieve long-lasting curls and waves. The kits typically included a complex set of instructions, small plastic curlers or rods, and two main chemical components: a “waving solution” containing a reducing agent (often thioglycolic acid) to break down the hair’s protein bonds, and a “neutralizer” (often hydrogen peroxide) to reform the bonds into a new, permanent curled shape. The process was notoriously messy, time-consuming, and often accompanied by a powerful, lingering, and unpleasant chemical odor. Results were highly inconsistent, ranging from perfect waves to an over-processed, frizzy disaster. As hair straighteners, better styling tools, and less damaging in-salon chemical services became available in subsequent decades, the market for these harsh, smelly, and unpredictable DIY home perm kits rapidly declined and they eventually vanished from mainstream store shelves.

13. Iceboxes Before Refrigerators

While electric refrigerators were invented in the early 20th century, they were not immediately universal across all American households in the early 1950s, particularly in rural or less affluent communities. These homes still relied on the icebox for short-term food preservation. An icebox was essentially a well-insulated cabinet, usually made of wood and lined with tin or zinc, that operated without electricity. Its function was dependent on a weekly or bi-weekly service: an iceman would deliver a massive, heavy block of ice, which was placed in a dedicated upper compartment of the box. The melting ice cooled the air, which circulated down to the lower compartments, keeping food perishables like milk and meat cold for a few days. The melted water was collected in a drip pan that had to be emptied regularly. The post-WWII economic boom made electric refrigerators widely affordable and accessible to the general public. Their convenience, superior cooling, and freedom from the messy, ongoing need for ice delivery quickly rendered the icebox a historical footnote, completing the transition to modern refrigeration.

14. Radio Tube Testers in Drugstores

In the 1950s, complex electronic devices like radios and the newly popular televisions were built using vacuum tubes, fragile, glass components that amplified and rectified electric current. These tubes were the most common point of failure, often burning out like a lightbulb. Because replacing every tube was expensive, a common scene in many drugstores, supermarkets, and hardware stores was the presence of a specialized machine: the radio and TV tube tester. Patrons would bring in a paper bag full of tubes from their broken device, and a self-service kiosk allowed them to plug in each tube to a variety of sockets to check if it was functioning. The machine would indicate which tube was dead, allowing the customer to purchase only the replacement needed. This unique retail ritual was instantly killed by the solid-state revolution. The invention of the far more reliable and long-lasting transistor in the late 1940s, and its mass market adoption in consumer electronics in the 1960s, completely eliminated the need for these fragile vacuum tubes, and with them, the ubiquitous tube tester kiosks.

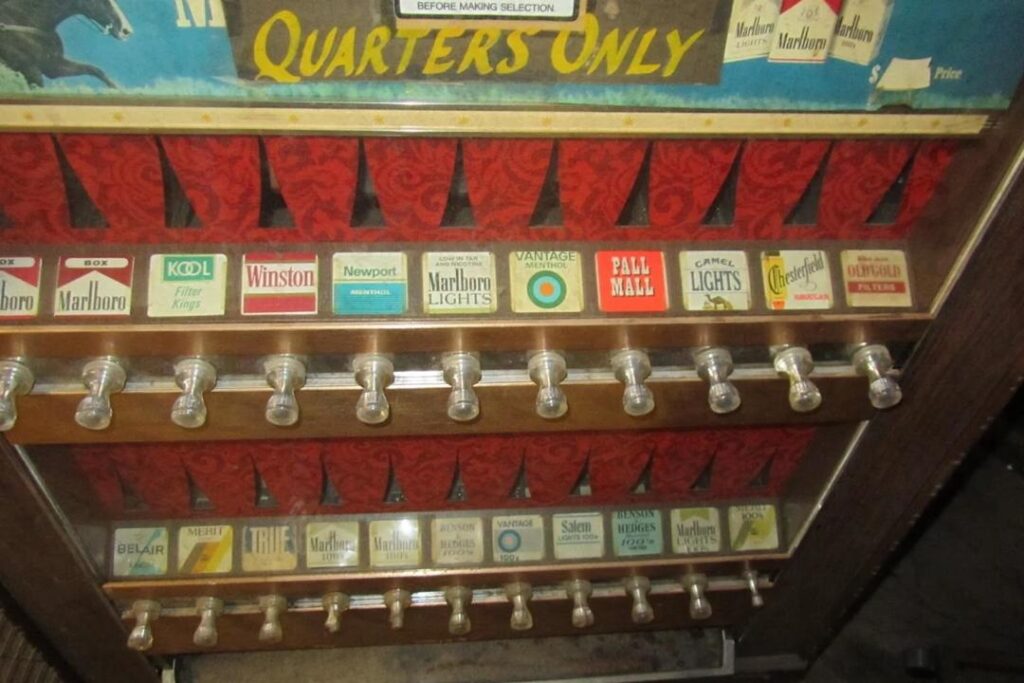

15. Cigarette Vending Machines

Before stringent age verification laws became standard, cigarette vending machines were a fixture of American public life, glowing in almost every casual social setting, including diners, bowling alleys, bars, and hotel lobbies. These attractive, chrome-detailed machines made purchasing cigarettes an immediate, cash-only transaction, and critically, there was no age verification required, anyone with the correct amount of coins could purchase a pack. They represented a pinnacle of convenience for smokers, offering major brands in an easily accessible format. The machines often had a visual appeal, with columns showing the brightly colored packs of cigarettes. However, as public health awareness grew and smoking began to be recognized as a dangerous addiction, the accessibility offered by these machines became a major point of contention. Tougher laws regarding the sale of tobacco to minors and a general decline in smoking rates led to a gradual legislative ban and removal of these machines from most public spaces. Today, they are virtually nonexistent in the United States, existing solely as a symbol of the tobacco industry’s once-unregulated cultural dominance.

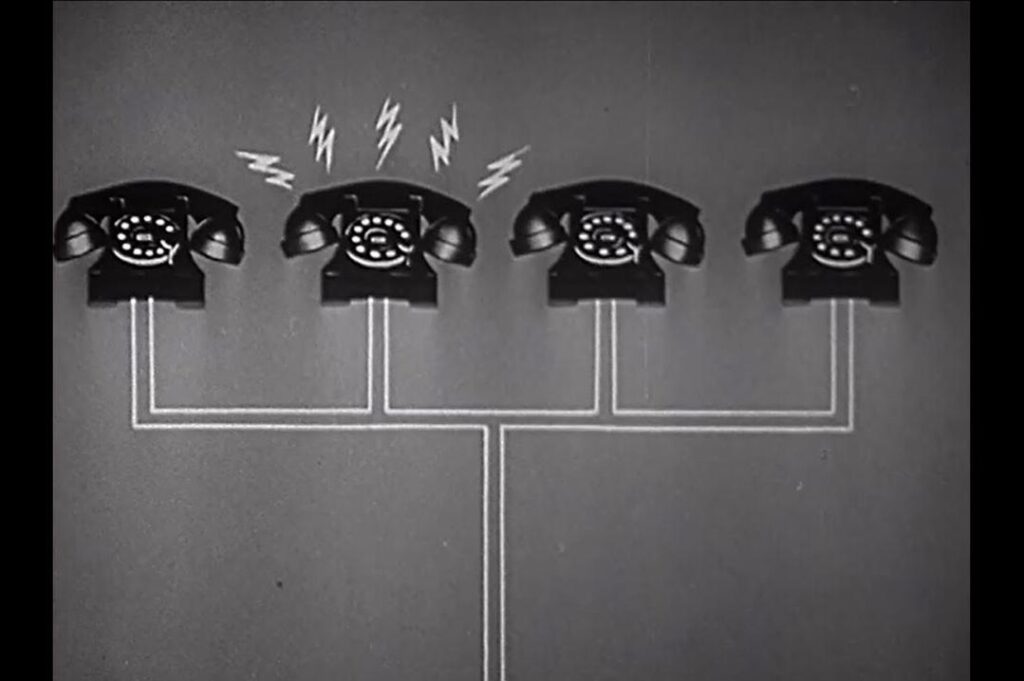

16. Party Line Telephones

The party line was a common arrangement in the 1950s, especially in smaller towns and rural areas, where multiple households shared the same single telephone circuit. Instead of a private, dedicated line, a home’s phone would share a common line with one or more neighbors. When one family was using the line, it would be busy for all other connected households. To alert the correct home, each subscriber had a unique “ringing pattern”, a specific combination of long and short rings. The lack of privacy was the defining feature; it was not uncommon for neighbors to pick up the receiver to listen in on conversations, a practice known as “rubbernecking”, or to get into minor arguments about “hogging the line.” While it made phone service more affordable and accessible to many, the constant lack of privacy was a major source of frustration. As telephone companies expanded infrastructure and technology became cheaper, the move to private, dedicated phone lines for every home became economically viable and a huge convenience. By the late 1960s and 1970s, the shared party line had almost entirely been upgraded and disconnected, becoming a memorable folklore story about the lack of modern privacy.

17. Metal Roller Skates with Keys

The classic metal roller skates were a childhood staple of the 1950s, offering a noisy, clattering form of outdoor fun. Unlike modern roller skates or rollerblades, these were not integrated into a shoe. They consisted of a four-wheeled metal frame with adjustable clamps designed to strap directly onto the child’s ordinary leather shoes. The key to their use was the skate key, a small, uniquely-shaped piece of metal that was used to tighten the clamps onto the shoe’s sole and heel. Children often wore the skate key on a string around their neck, symbolizing their independence and access to fun. The skates were notoriously imperfect; they frequently loosened mid-ride, causing the child to have to stop and re-tighten the clamps with their key. They produced a loud, unmistakable clatter on sidewalks and paved roads. Modern sports equipment, such as rollerblades and integrated skate shoes with plastic wheels and fixed boots, offered superior stability, comfort, and safety. These innovations entirely replaced the cumbersome, noisy, and adjustable metal skates, leaving the little skate key as a nostalgic emblem of mid-century childhood.

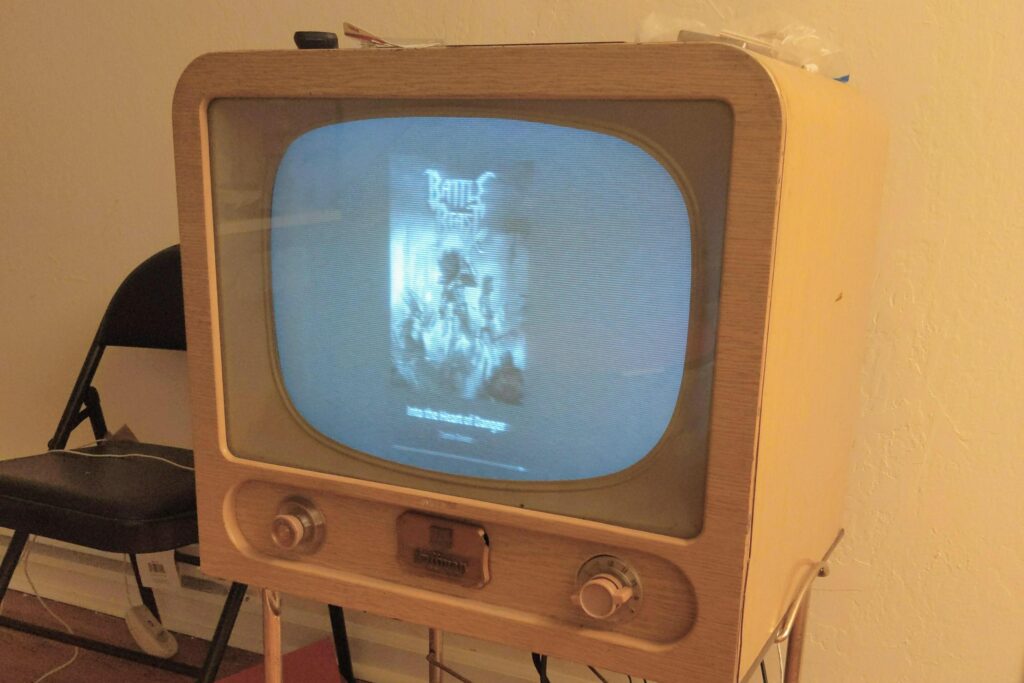

18. Vacuum Tube Televisions

Early televisions of the 1950s were technological marvels but were fundamentally reliant on vacuum tubes for their operation. These were the same glass components used in radios, and in a TV, hundreds of them were required for the complex processes of tuning, amplification, and image display. The resulting TVs were massive, heavy pieces of furniture, typically encased in large wooden cabinets. Because the vacuum tubes generated significant heat and had a limited lifespan, they were prone to burning out frequently, causing the picture or sound to fail. This led to a thriving business for neighborhood TV repair shops. Homeowners often had to wait for a technician to diagnose and replace the faulty tube, a common and expensive inconvenience. The entire industry was revolutionized by the development of solid-state electronics in the 1960s and 1970s. This transition saw the fragile, heat-producing vacuum tubes replaced by reliable, tiny, and long-lasting transistors and integrated circuits. The shift allowed televisions to become lighter, smaller, cheaper, and vastly more reliable, effectively making the tube-based set a technological dinosaur.

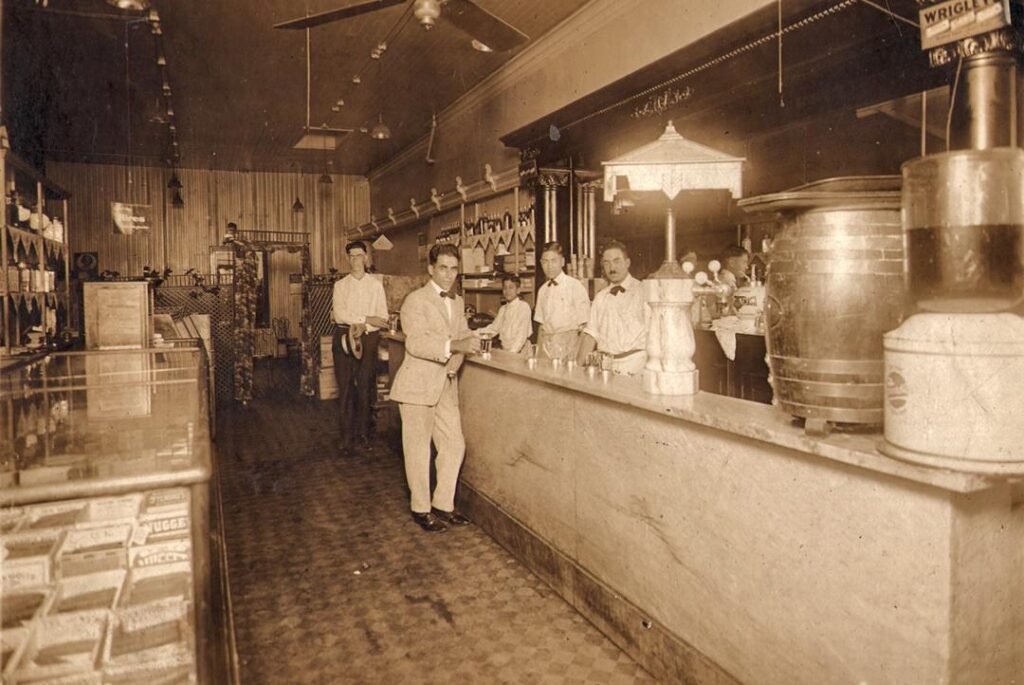

19. Soda Fountains in Pharmacies

For most of the 1950s, the local pharmacy (or “drugstore”) was not just a place to pick up prescriptions; it was a central community hub, thanks to the presence of the soda fountain counter. This counter, often lined with swivel stools and featuring polished stainless steel, was where a “soda jerk” (the fountain attendant) would craft classic American refreshments. Children and teens flocked to them after school for treats like cherry cokes, chocolate malts, banana splits, and ice cream floats. These fountains served as a social meeting point, a small, independent precursor to the modern cafe or diner. They offered a unique, often personalized customer experience that transcended simple retail. However, the expansion of the fast-food industry, the rise of specialized ice cream and beverage shops, and the increasing market dominance of large-scale chain supermarkets that did not feature fountains began to erode their purpose. As drugstores streamlined their operations to focus purely on health and retail, the charming, labor-intensive, and unprofitable soda fountain counter was gradually dismantled, surviving only in preserved diners and as a potent image of small-town mid-century life.

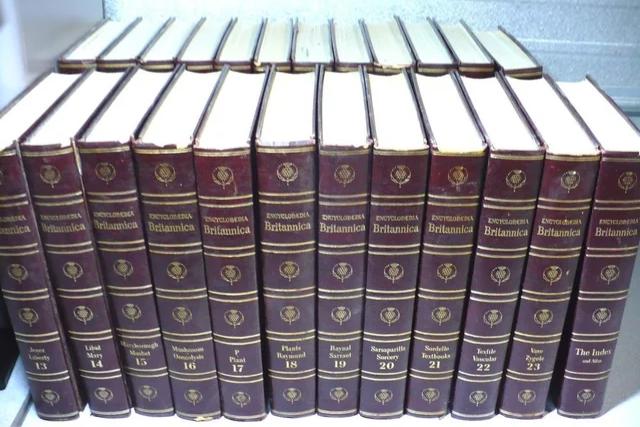

20. Encyclopedias in Every Home

In the 1950s, owning a complete, multi-volume set of encyclopedias, such as Encyclopedia Britannica or World Book, was a universal symbol of a dedicated, educated household. Often purchased through door-to-door salesmen on installment plans, these expensive, heavy books were considered the ultimate repository of knowledge, essential for a child’s education and for settling family arguments. They were the go-to reference for homework, research papers, and general curiosity. The challenge, of course, was that the information was static, meaning the sets became outdated the moment they were printed. Families would occasionally buy annual updates, but the core volumes remained largely the same. The internet, with its search engines, instantaneous updates, and near-limitless depth of free information (most notably Wikipedia), delivered a deathblow to the bound encyclopedia. By the early 2000s, the sale of these physical sets had virtually collapsed, turning the once-mandatory 20+ volumes into bulky, seldom-opened fixtures in the attic or garage sale finds, marking a decisive end to the era of physical, contained knowledge.

21. Shoe-Fitting Fluoroscopes

The shoe-fitting fluoroscope, also popularly known as a pedoscope, was a bizarre, now-unthinkable technology found in many shoe stores in the 1950s. Designed to ensure a perfect fit, this device allowed the customer and salesperson to view the bones of the foot through the leather of a newly tried-on shoe. The machine was a wooden cabinet with three viewing ports, one for the salesperson, and smaller ones for the child and parent, and was essentially an unshielded, low-power X-ray machine. Kids often enjoyed the experience, watching their toes wiggle as green-tinged shadows. The supposed benefit of seeing the fit was immediately outweighed by the severe, unmanaged health risks. Both customers and the sales staff were unknowingly exposed to low, but repeated, doses of radiation. As knowledge about the dangers of X-ray exposure grew and scientific bodies released warnings, a wave of regulatory actions across various US states and Canada began in the late 1950s and 1960s. By the 1970s, safety concerns had led to the complete ban and removal of these dangerous devices from public retail use, making them one of the most shocking and forgotten relics of mid-century consumer life.

22. Poodle Skirts and Saddle Shoes

The poodle skirt and its companion, the saddle shoe, were two of the most recognizable and enduring fashion symbols of the 1950s youth culture, particularly associated with rock ‘n’ roll and high school dances like sock hops. The poodle skirt was a wide, brightly colored felt circle skirt, typically featuring a silhouette of a French poodle with a rhinestone-studded leash appliquéd near the hem. It was designed to swing dramatically during fast dances. The shoe of choice to complete this look was the saddle shoe, a leather oxford shoe that was usually white with a contrasting color (often black or brown) piece of leather over the middle, giving it a distinctive “saddle” appearance. Both items were essential for a fashionable young woman’s wardrobe and were ubiquitous on school campuses. However, like all fads, their popularity was short-lived. By the mid-1960s, these looks were replaced by the slimmer, more modern lines of Mod and Beatle-inspired fashion. While they have completely vanished from everyday wear, they remain a powerful and charming costume staple for theme parties and theatrical productions, keeping the memory of 1950s teen style vividly alive.

23. Handwritten Letters on Stationery

In the 1950s, personal correspondence was an established art form centered on the practice of sending handwritten letters on formal stationery. Families kept specialized boxes of monogrammed or personalized stationery, often featuring heavier, high-quality paper and matching envelopes. Unlike today’s rapid-fire emails or texts, writing a letter was a careful, thoughtful process that adhered to certain social etiquette regarding tone and structure. It required a good pen, a clear hand, and time dedicated to composition. Letters were often used for maintaining long-distance relationships, expressing formal gratitude, or delivering important family news, and their arrival was a significant event. The physical act of writing with care made the communication feel personal and lasting. The invention and widespread adoption of the home telephone began the slow process of moving communication from the page to the voice. Later, email and text messaging provided a free, instantaneous, and casual alternative. While personalized stationery still exists, the ritual of daily, essential communication via a thoughtful, handwritten letter has faded away, replaced by the digital word.

24. Cigarette Lighters Built into Cars

In the 1950s, when smoking was a socially accepted, nearly universal habit, a built-in cigarette lighter was a standard feature in nearly every American automobile. Located on the dashboard, often near the ashtray (another standard feature), the device was a simple electrical coil set inside a pull-out metal knob. The driver or passenger would push the knob in to complete an electrical circuit, heating the coil to a glowing red-hot temperature. After a short wait, the knob would pop out, and the user would remove the entire unit to light a cigarette. This feature was considered essential for driver convenience and safety (as lighting up with a match while driving was hazardous). The rise of anti-smoking campaigns, increasing health consciousness, and a general decline in the rate of smoking drastically changed the car interior. By the late 1990s, the actual lighter coil was often omitted from new cars. Today, the socket itself has been repurposed as a universal 12-volt power outlet for charging phones, GPS devices, and other accessories, almost entirely obscuring its original, tobacco-centric purpose.

25. Home Movie Projectors

Gathering in the living room for a “home movie night” was a popular family pastime in the 1950s, made possible by 8mm or Super 8 film cameras and their accompanying, often noisy, projectors. These projectors used a light source and a lens to shine the image from the small reels of film onto a retractable screen or a white wall. The films were usually short, silent, and often shaky footage of birthdays, holidays, and family vacations. Setting up the projector, threading the film, focusing the lens, and dealing with the ever-present risk of the film jamming, snapping, or melting under the lamp’s heat, was part of the ritual. Despite the technical inconveniences, it offered a unique, shared, and communal viewing experience. The introduction of portable video cameras (camcorders) and the popular VHS tape format in the late 1970s and 1980s made recording and playback vastly easier, cheaper, and higher quality. This transition quickly sent the delicate film reels and the cumbersome, mechanical home movie projector into storage, making the flickering light of the 8mm projector a powerful nostalgic memory.

26. Jell-O Salad Molds

In the 1950s, the Jell-O salad mold was a ubiquitous, often mandatory item on the table at any church supper, potluck, or family gathering. These creations were a cultural phenomenon that fused the bright colors and sweet flavors of gelatin (Jell-O) with various solid additions. Recipes often ventured far beyond simple fruit, incorporating everything from marshmallows, grated carrots, cottage cheese, pretzels, or even canned tuna into the wobbly, often ring-shaped mold. The goal was to create a visually appealing, jiggly centerpiece that served as a sweet-savory side dish. The specific, often elaborate, metal or plastic molds designed to create these perfect shapes were common kitchen tools. By the 1970s and 1980s, American culinary tastes began to shift toward more natural, less processed, and less kitschy foods. The Jell-O salad mold gradually lost its status as a sophisticated dish and began to be seen as a relic of a previous, more eccentric culinary era. Today, the practice is a subject of historical curiosity and irony, completely removed from its former prestige as a necessary part of entertaining.

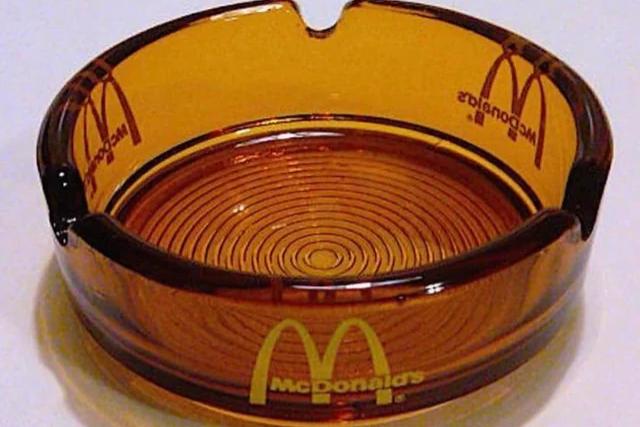

27. Ashtrays in Every Room

The pervasiveness of smoking in the 1950s meant that ashtrays were not merely accessories; they were an essential, decorative, and functional part of the décor in virtually every room of a home, office, and public space. They came in a vast array of materials, from heavy, clear glass to elaborate ceramic and ornate metal designs, often chosen to match the room’s furniture or color scheme. It was considered a matter of common courtesy to have an ashtray available for any guest who might be smoking, and it was fully expected that one might smoke inside homes, offices, and even hospitals. The sheer number of ashtrays needed, one for every end table, desk, and gathering spot, made them a major household commodity. The surge of public health awareness regarding the dangers of secondhand smoke and the subsequent social and legislative campaign against indoor smoking was the undoing of the ubiquitous ashtray. As more places became smoke-free and the number of smokers declined drastically, the necessity for the item vanished. Today, an ashtray in a home is a rare sight, standing as a quiet indicator of a major societal shift away from universal indoor smoking.

28. Grocery Store Trading Stamps

The practice of collecting grocery store trading stamps was a major consumer incentive and a near-universal ritual for families in the 1950s. Companies like S&H Green Stamps or Top Value Stamps were issued by the cashier based on the amount of a shopper’s purchase, for every dollar spent, a certain number of stamps were received. The excitement was in the collection: customers would take the tiny, gummed stamps home and meticulously lick and paste them into dedicated collector booklets. Once a book was filled (often requiring hundreds of stamps), it could be redeemed at a redemption center for a wide array of “free” merchandise, ranging from household appliances, toys, and furniture. This system created fierce brand loyalty among shoppers eager to fill their books. The complexity and cost of running the redemption centers, coupled with the rise of computerized loyalty programs (like store points cards and instant discounts) that offered more immediate gratification, gradually phased out the paper stamp system. The final glue-smudged booklet became a relic of a time when small, tangible rewards fueled consumer loyalty.

The 1950s were a time of rapid invention, where every household relied on unique products and services that streamlined life in their own way.

This story 28 Once-Essential Products from the ’50s That No Longer Exist Anywhere was first published on Daily FETCH