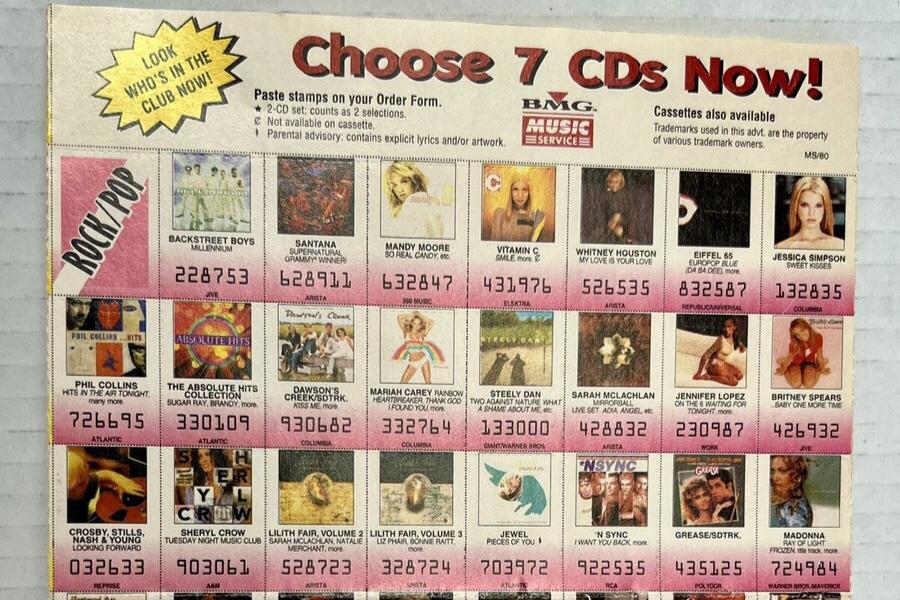

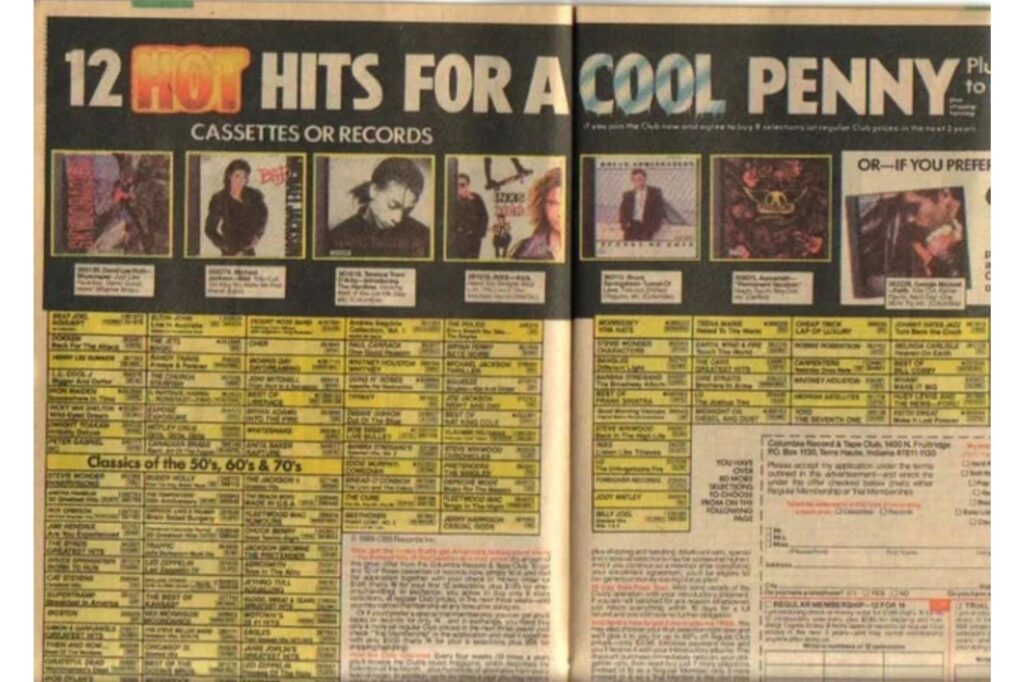

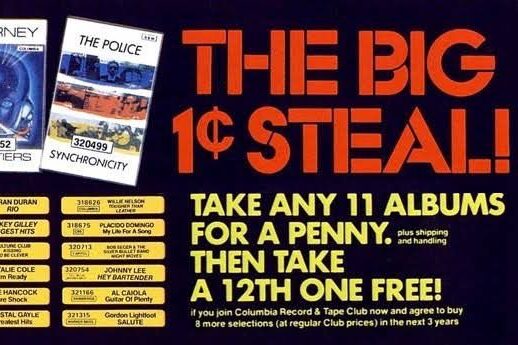

1. The Stamp Sheets Felt Like a Game and a Contract

That glossy, fold-out brochure wasn’t just an ad; it was the start of an adventure. You’d receive a sheet of tiny, lick-and-stick album-cover stamps and meticulously place twelve favorites onto the grid. It felt like building a new playlist or crafting an alter-ego, you could be a hip-hop head on Tuesday and an alternative rock purist by Friday. The process felt like pure play, a low-stakes exercise in dreaming up your perfect library. However, that delightful sticking ritual was, in fact, signing you up for a long-term, legally binding negative-option plan. You’d committed to purchasing several full-price CDs later. Worse, you were agreeing to the terms of the monthly “Selection of the Month”, meaning, unless you mailed back the designated card opting out, you’d be automatically shipped (and billed for) the featured album. Many households learned about the power of the postal service (and the cost of a missed deadline) when an unwanted Hootie & the Blowfish album appeared on the doorstep.

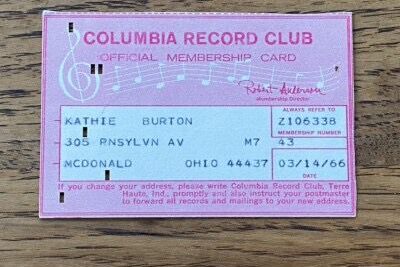

2. It Started with Records, Then Tapes, Then CDs and the Longbox Era

The concept of music delivered by mail didn’t begin with the shiny silver disc; Columbia House was already a staple in the 1960s vinyl era. They efficiently scaled through the cassette tape craze, but the model truly hit its stride and became an American retail fixture with the rise of the Compact Disc. The timing was perfect, aligning with the CD’s explosive growth in the late 80s and early 90s. When those early CD club shipments arrived, the discs were often housed in cardboard longboxes. These oversized packages were initially created for retail stores, designed to deter theft and fit vinyl-era display racks, and they were mailed to club members, too. Unboxing a CD in its longbox felt premium, like opening a tiny, full-color billboard for your music. While stores eventually ditched them for environmental and cost reasons, those weird sleeves continued to show up in recycling bins for years, a testament to the club’s massive influence and volume.

3. “12 for a Penny” Wasn’t the Whole Bill, Shipping Did the Heavy Lifting

The introductory offer was the ultimate, almost irresistible hook: a dozen albums for just one cent. It was a masterclass in psychological marketing, delivering a massive flood of choice for virtually no upfront cost. The true cost of the club, however, was cleverly hidden in the fine print and delivered in installments. First, there was the necessary evil of Shipping and Handling (S&H), which was charged on those twelve “free” CDs, often amounting to a small but noticeable fee per disc. This immediately generated a small cash flow and covered the logistics. The real business model was the commitment: you promised to purchase a small number of full-price selections, usually six to eight, over the following one or two years. These full-price selections were often sold at a premium compared to discount big-box stores. This guaranteed revenue stream, combined with the occasional missed “no-thanks” card, is where the profit was truly made.

4. Negative Option = “Do Nothing, Buy Something”

The negative-option purchase was the core mechanism that drove the club’s consistent sales volume and, often, a member’s frustration. Every month, members received a postcard or brochure detailing the “Selection of the Month”. The system was designed to put the onus entirely on the member: you could choose an alternate title, add a few extras, or use the card to decline the offer altogether. The critical part was the default: failure to respond to the card before the deadline resulted in the automatic shipment (and billing) of the featured album. This efficiency was fantastic for Columbia House and BMG, ensuring a predictable stream of sales. For busy high school and college students, however, that little card was easily lost in the chaos of a backpack or a dorm room desk. This model of “do nothing, buy something” was the financial engine of the clubs and a major source of unexpected charges on household bills.

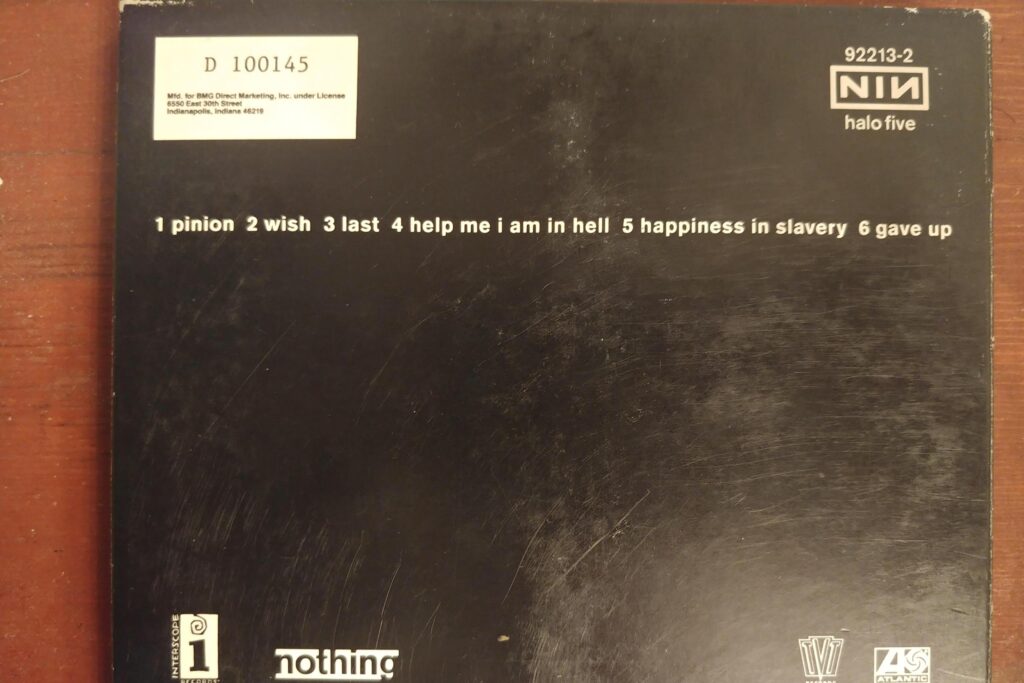

5. Record-Club Editions: Same Album, Slightly Different Beast

While the vast majority of CDs received were sonically identical to the versions found in retail stores, savvy collectors and audiophiles would often spot subtle differences. These were the “Record-Club Editions.” The most common identifiers were codes like “CRC” (for Columbia Record Club) or simply the imprint of “BMG Direct Marketing, Inc.” printed on the disc or the back cover. This indicated the album was pressed specifically for the mail-order service, often at a different manufacturing plant than the retail version. Sometimes, the packaging would be slightly tweaked: a thinner liner note booklet, a less glossy finish on the tray card, or a different barcode placement. While intense debates raged among music fans about whether these pressings sounded different (the consensus was almost always no), these codes meant the resale value could be a hair lower on the used market. Still, when you acquired a dozen discs for a single cent, the minor details of the matrix number rarely factored into the purchase decision.

6. The “Multiple Memberships” Legend Had Chapters

The incredible deal of “12 CDs for a penny” inspired thousands of teenagers and young adults to try and game the system. The urban legend suggested you could simply sign up again to restart the introductory offer, using slightly different information to bypass the system. People experimented with signing up under roommates, cousins, parents, or using variations of their own name, like dropping a middle initial or changing a nickname, or even a post office box to keep the penny party going. This practice made many young people tiny logistics managers, tracking different commitment schedules and payment due dates. Naturally, the clubs eventually caught on. Columbia House and BMG gradually tightened controls, matching addresses, monitoring payment histories, and implementing stricter identity checks. For those who defaulted on their purchase commitments, the clubs were known to employ collection agencies, providing many teens with their first, often harsh, lesson in credit consequences and financial responsibility.

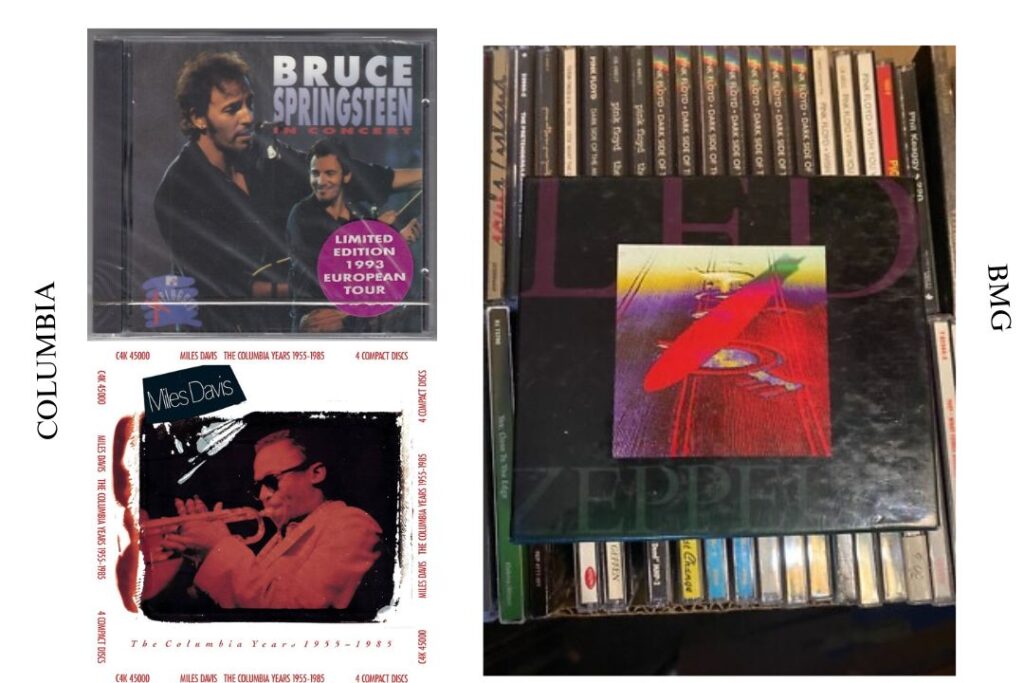

7. Columbia House vs. BMG: The Friendliest Arms Race

For a significant period in the late 1980s and 1990s, the music club landscape was dominated by two fierce rivals: Columbia House and BMG (Bertelsmann Music Group). This competition created a vibrant, constantly escalating environment for consumers. If Columbia House could boast a deep catalog of established artists like Bruce Springsteen and Miles Davis, BMG would counter with exclusive offers for massive sellers like Led Zeppelin box sets or popular alternative bundles. The rivalry was fought through the mail, with each club mailing increasingly thicker, more colorful catalogs designed to tempt customers. They consistently added bonuses like “buy one, get three free” moments, limited-time coupons, and “five more for just $1.99 each” up-sells. Consumers, often subscribed to both, became tiny comparison-shopping experts, flipping through pages of miniature album covers and catalog codes to determine which club offered the best deal for completing their required full-price purchases.

8. Those Fulfillment Warehouses Were Quiet Hit Machines

In the early 1990s, the music industry’s official sales tracking system, SoundScan, primarily focused on retail store sales and generally did not count music club shipments in its weekly charts. Despite this, the clubs moved a truly staggering volume of material, making them quiet, massive hit machines. While they sold current pop and rock hits, their true commercial strength lay in catalog titles (albums older than 18 months) and consistent sellers like adult contemporary artists, crooners, and classic rock acts. Artists with long commercial tails, those whose music remained popular for decades, benefited enormously. Every week, massive fulfillment warehouses, often operating with forklifts and complex conveyor systems, would quietly process millions of orders. These operations were responsible for minting vast numbers of new music libraries across suburban rec rooms and college dorms, with millions of copies of “Best of The Eagles” or easy-listening staples heading out the door.

9. Mail Culture Made Music Feel Earned

In an age defined by digital downloads and instant streaming, it is easy to forget the value placed on waiting and anticipation. For club members, the music wasn’t just acquired; it was earned. After sending off the stamp sheet and the check, the waiting game began, turning the home mailbox into a scoreboard. The sight of that corrugated carton, often slightly crushed from its postal journey, was a moment of genuine triumph. Tearing into the cardboard, stacking the jewel cases like trophies, and then meticulously decoding the spines for a place on the shelf transformed consumption into a ritual. This process created a physical and emotional connection to the purchase. Playlists weren’t created by drag-and-drop; they were structured around a calendar of arrivals. This mail-order culture taught a generation patience and sequence, making the first listen of a brand-new, physically owned album on a Tuesday afternoon a small, memorable victory.

10. It Ended with a Whimper, but the Habit Lives On

As the new millennium dawned, the music club model faced a death-by-a-thousand-cuts scenario. Big-box retailers like Walmart and Best Buy began to heavily discount CDs, eliminating the price advantage of the premium-priced commitment albums. More fatally, the rise of Napster, iTunes, and digital streaming made the wait for a physical shipment completely obsolete. The clubs’ revenue streams evaporated, leading to bankruptcies, sales, and eventual collapse. Columbia House, the last major club standing, officially filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2015. However, the club’s ingenious, psychologically potent pitch, “pay little now, commit later”, did not die. It merely migrated. That same rush of choice up front, followed by the lurking fine print, is now the business model for countless subscription boxes, free-trial streaming services, and membership deals. We are still chasing that first-month high, and the same old question remains: Will we remember to send the cancellation notice back before the bill arrives?

This story 12 CDs for a Penny, 10 Things We Forgot About Columbia House (and BMG), Music’s Wildest Mail-Order Hustle was first published on Daily FETCH