1. It started with a lizard and a mission

Back in 2016, a team of scientists at the University of Massachusetts took on something unusual: they scanned a Cuban knight anole lizard in full 3D. That simple scan sparked the Digital Life Project, a mission to digitally capture every species on Earth. The idea wasn’t just to make lifelike models but to create permanent, high-resolution records of animals, especially those at risk of vanishing forever. This first lizard scan proved that with the right mix of technology and creativity, it was possible to preserve an animal’s exact shape, texture, and even how it might move, all without causing it harm. From there, the project grew, inspiring collaborations worldwide and opening doors to the idea of a vast, digital archive of life.

2. Like Pokémon, but real and vanishing

The scanning process looks a bit like designing a video game character, only the stakes are much higher. Scientists use dozens of synchronized cameras and lasers to capture an animal from every angle, building ultra-detailed 3D avatars. Imagine being able to rotate a frog or a chameleon just like you’d study a digital Pokémon card, except these creatures are real, and many are endangered. These models aren’t rough outlines; they include textures, colors, and proportions accurate down to the tiniest scales or feathers. Sadly, some of the species being scanned may disappear in the wild, leaving only these digital doubles behind. In that sense, each scan becomes a record of something fragile, reminding us that what looks like “virtual fun” is actually serious preservation work.

3. A Noah’s Ark made of pixels

For centuries, people have dreamed of saving animals two by two in wooden boats. Today’s version is happening on hard drives and in digital archives. By creating 3D models of living creatures, scientists hope to preserve them in ways that can benefit science, education, and conservation. These models can even be used in virtual reality, letting future generations “walk around” species that no longer exist. Some researchers even see potential for rewilding projects, where knowledge of an animal’s exact form could help restore balance to ecosystems. While a digital scan can’t save an endangered species outright, it can safeguard details of its existence, ensuring that its presence is never forgotten. In that sense, this new “ark” is less about transporting animals and more about preserving memory, knowledge, and hope.

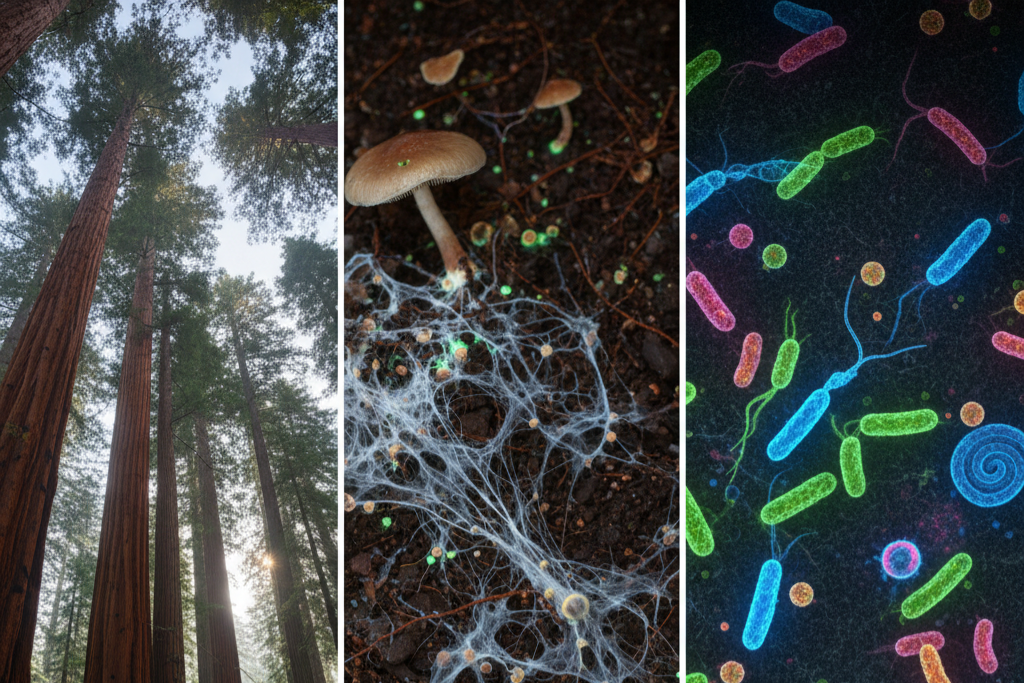

4. It’s not just animals anymore

What began as a focus on animals is now expanding into something even larger. The Global Digital Biodiversity initiative aims to digitally record not just animals but every living thing on Earth. That includes plants like towering redwoods, fungi that thrive underground, and even bacteria invisible to the human eye. This ambitious effort recognizes that life is interconnected and that protecting biodiversity means documenting it all, not just the big, charismatic species. When people think of biodiversity, they often picture the roughly 1.5 million animal species that have been identified and named. But scientists believe the true number of life forms on Earth could be staggering, perhaps over a trillion, especially when you factor in microbes, fungi, and other microscopic organisms. Many of these species remain undiscovered, and some may vanish before they’re ever documented. That’s why the race to digitize is so urgent.

5. The urgency is real

We’re living in a time when species are disappearing faster than scientists can keep up. Many animals and plants are vanishing before they’ve even been named or studied, and climate change, habitat loss, and human activity only speed up the process. That’s what makes projects like Digital Life so vital, they provide a chance to preserve what we can, even if the living versions are gone tomorrow. Think about it: without these records, future generations might never know what certain frogs, fish, or insects even looked like. Digitization doesn’t replace conservation in the wild, but it acts as a safety net, giving us at least one way to hold onto the details of life before they slip away.

6. One model can replace a thousand specimens

Traditionally, science students and researchers had to rely on preserved specimens, animals and plants kept in jars, drawers, or displays. While these collections are valuable, they also have limits: they can degrade, they take up space, and they often involve removing creatures from the wild. A 3D model, by contrast, can be studied endlessly without harming a single animal. Students can rotate it, measure it, zoom in, and even simulate how it moves. One detailed digital scan can take the place of countless physical samples, offering a humane and practical alternative. This approach also democratizes learning, giving classrooms around the world access to models they might otherwise never encounter.

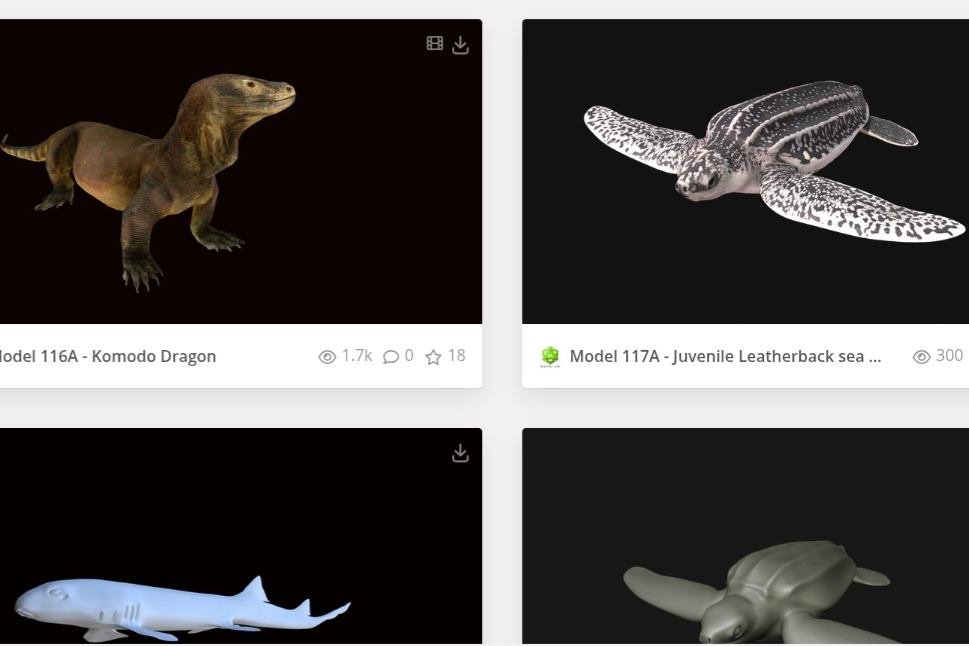

7. They’re already online and viewable for free

You don’t have to be a scientist to explore these digital creatures. Many of the 3D models created through the Digital Life Project and similar efforts are available to the public at sites like digitallife3d.org. Visitors can rotate a panther chameleon as if it were a sculpture, examine the saw-like snout of a rare sawfish, or explore other species in lifelike detail. It’s like having a digital museum at your fingertips, and it’s open to anyone with internet access. By making these resources free, the projects aim to spark curiosity and connect more people to the natural world. For many, seeing these animals up close online may be the closest encounter they’ll ever have with such rare species.

8. Field scanning is the next frontier. Can a scan really save a species?

So far, many of these scans have taken place in controlled settings like zoos or labs, where animals can be carefully positioned for imaging. But the dream is to take this technology into the wild. Portable scanning equipment is being developed that could capture animals in their natural habitats, without needing to move them or disrupt their lives. Imagine scanning a sea turtle as it swims, or recording the intricate wings of a butterfly while it flutters in a forest clearing. These records can also guide future conservation efforts, helping scientists understand species anatomy, movement, and behavior in ways that could support protection or even reintroduction efforts. In the long run, digital scans may not directly save species, but they can play a powerful role in preventing total loss by keeping memory and science alive.

9. This isn’t the only digital Noah’s Ark

The Digital Life Project is one of several efforts around the world racing to preserve biodiversity in new ways. The Virtual Herbarium is cataloging plants with high-resolution scans, while Open Zoo is creating a digital record of living animals. The Smithsonian is also digitizing vast insect collections, capturing details so fine you can see individual hairs. Each project may have a slightly different focus, but together they form a global network of digital preservation. It’s a reminder that biodiversity isn’t just about the charismatic species we know well, it’s about everything from towering trees to tiny bugs, all of which play a part in keeping ecosystems healthy.

10. You can help this global race

This isn’t a project limited to scientists with labs full of cameras. Many organizations invite the public to join in by contributing images, helping identify species, or even supporting digitization efforts financially. Citizen science platforms allow ordinary people to upload wildlife photos, which can feed into databases that guide scanning projects. The message is clear: the digital Noah’s Ark belongs to all of us, and protecting biodiversity is a shared responsibility. By getting involved, even in small ways, people everywhere can help ensure that Earth’s incredible variety of life is recorded before it’s too late.

In the end, these pixelated creatures remind us of the real ones we still have, and why it’s worth fighting to keep them here.

This story 10 Wild Facts About the Race to Digitally Capture Every Living Creature on Earth was first published on Daily FETCH