When we think of beachcombing, we picture seashells, driftwood, and maybe a crab or two scuttling by. But the real magic lies beneath the rocks, where entire micro-worlds unfold in crevices just inches wide. Flip one over (gently!) at low tide, and you might uncover creatures with iridescent armor, alien-like feelers, or the ability to regenerate limbs. From frigid northern coastlines to balmy southern estuaries, each U.S. coastal region has its own strange cast of characters hiding in plain sight.

Here are 24 of the wildest under-rock creatures you can find along America’s shores, organized by region, one surprising critter at a time.

1. Green Shore Crabs – New England & Mid-Atlantic

Green shore crabs may look like just another typical crustacean. Still, they’re one of the most aggressive invaders on the American coastline. Originally from Europe, they were likely introduced to the East Coast in the 1800s via ballast water and have since exploded in number. Today, their populations can reach over 100 crabs per square meter in some New England tidepools, outcompeting native crabs and preying heavily on bivalves, worms, and small fish. They’re easily identified by their five spines beside each eye and their ability to dart quickly under rocks the moment they’re disturbed.

These crabs are not just quick; they’re hardy. They can survive in a wide range of salinities and temperatures, even withstanding several days out of water in damp conditions. Their claws are surprisingly strong for their size, capable of cracking through the shells of small mollusks with ease. Scientists have studied them as a model species for invasive behavior, given their adaptability and aggressiveness across various marine ecosystems. If you’re flipping over rocks along the coast of Maine or the Jersey Shore, odds are high that one of these emerald intruders is already looking back at you. Source: Smithsonian Institution

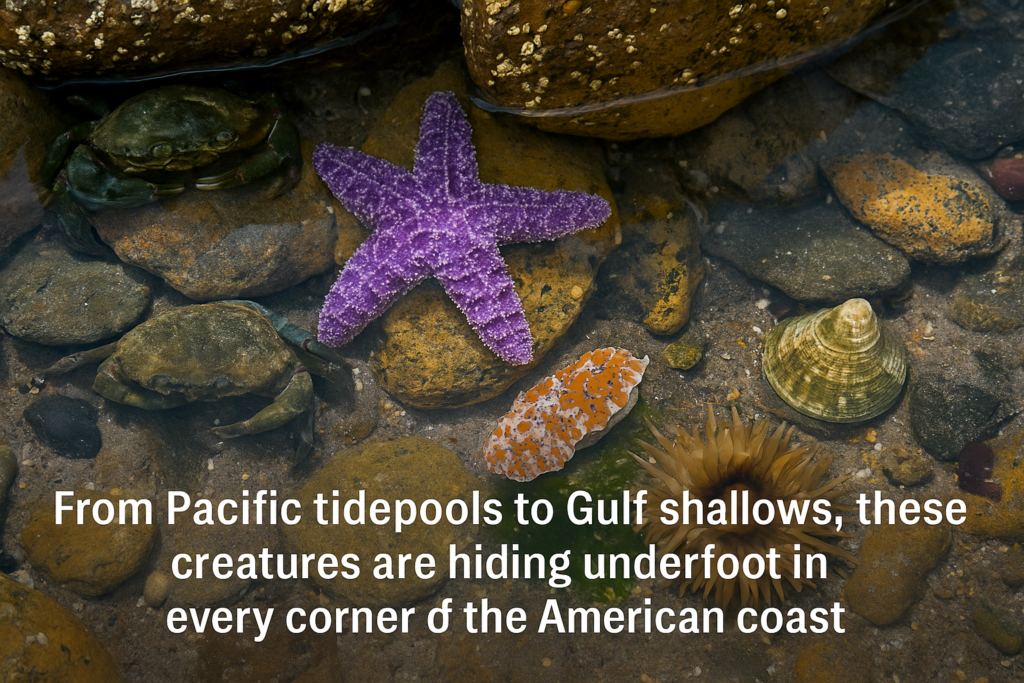

2. Sea Slugs (Nudibranchs) – Pacific Northwest & California

Sea slugs, or nudibranchs, are the flamboyant showstoppers of the Pacific tidepools. These soft-bodied mollusks come in electric blues, fiery oranges, vivid purples, and striking patterns that seem too bold to be real, yet they are. Found under rocks and kelp mats from Oregon to Southern California, nudibranchs are often no bigger than your finger, but their visual drama is unmatched. Some species are more than just eye candy: they can grow up to 12 inches long and have evolved the astonishing ability to steal toxins or stinging cells from their prey, like jellyfish or anemones, and incorporate them into their tissues as a defense.

Nudibranchs lack shells, which makes their chemical defenses and camouflage all the more critical. They crawl slowly along rocks using a broad foot, sensing the world with delicate tentacle-like rhinophores on their heads. These sea slugs are hermaphroditic, meaning each individual possesses both male and female reproductive organs, which increases reproductive efficiency in the sparse world of tidepools. Some even glow under UV light or fluoresce in the dark, making them popular among both underwater photographers and marine biologists. With over 3,000 known species globally and dozens unique to the Pacific Coast alone, each encounter is like discovering a tiny underwater piece of neon art. Source: Pacific Beach Coalition

3. Sand Crabs – Gulf Coast & Southern California

Sand crabs, also called mole crabs, are the unsung burrowers of the surf zone, creatures you’ll rarely see unless you know to dig for them. About the size of a human thumb, they have rounded, bullet-shaped bodies and no visible claws, making them look more like gray jellybeans than crustaceans. But beneath the wet sand of beaches from the Gulf Coast to Southern California, these crabs are in constant motion. With every receding wave, they back into the sand headfirst, using their powerful legs to disappear in seconds. Once buried, they use long, feather-like antennae to catch plankton from the water column, filtering up to 20,000 particles a day.

Despite their small size, sand crabs play a massive role in beach ecosystems. They provide a critical food source for shorebirds like sanderlings and plovers. They are used in scientific studies to monitor environmental health due to their sensitivity to toxins and pollutants. During low tide, you can often spot their V-shaped feeding marks in the wet sand, primarily where waves gently lap the shoreline. Some beaches even host seasonal “crab tides,” mass migrations where hundreds emerge to spawn. Gentle and entirely harmless to humans, these little creatures are nature’s hidden tide readers, living just beneath your toes. Source: Wildcoast

4. Rock Gunnels – New England Coast

Rock gunnels are slippery, eel-like fish that call the crevices and under-rock hideouts of New England’s intertidal zones home. At first glance, you might mistake them for juvenile eels or sea snakes due to their elongated bodies and undulating movements. Usually around 6 to 12 inches long, they sport a mottled pattern of reddish browns or greens that lets them blend into rocks coated in algae or barnacles. What makes rock gunnels particularly fascinating is their ability to survive prolonged periods out of water, thanks to a moist, mucus-covered skin that lets them absorb oxygen directly from the air. Some individuals can breathe this way for hours, wriggling through wet kelp and under rocks even when the tide is out.

They’re generally shy, darting from shadow to shadow and feeding on small crustaceans, worms, and mollusks. Their compressed bodies make it easy for them to squeeze into impossibly tight crevices, offering protection from predators and beachcombers alike. Rock gunnels also have a curious ability to stiffen when handled, a defense mechanism that makes them feel like rubbery sticks. Though often overlooked in favor of flashier tidepool residents, they’re critical indicators of intertidal health. They are known to withstand cold, low-oxygen waters better than many other fish species. Lift the right rock along the Maine coast, and you may catch a glimpse of one slinking away like a little dragon of the shallows. Source: Mass.Gov

5. Chitons – California & Oregon Coasts

Chitons may look like ancient fossils clinging to coastal rocks, and that’s not far from the truth. These primitive mollusks, found on wave-swept shores from central California to Oregon, have roamed Earth’s oceans for over 500 million years. They resemble armored ovals, typically 1 to 3 inches long, with eight overlapping plates running down their backs. This segmented armor allows them to flex and conform tightly to uneven rock surfaces, where they cling with a muscular, suction-like foot so strong that even crashing waves can’t dislodge them. What makes chitons especially remarkable is their feeding mechanism: they use a radula (a tongue-like ribbon lined with rows of magnetite-coated teeth, the most rigid material produced by any animal) to scrape algae off rocks like living sandpaper.

Chitons are primarily nocturnal, venturing out at night to graze and retreating into cracks during the day. Their muted colors, often brown, green, or rust, make them easy to miss unless you’re deliberately looking for the patterned shells. Some species even develop a camouflage of tiny algae and barnacles growing on their backs. Though they move slowly, chitons have a phenomenal homing ability and often return to the same spot after foraging, leaving behind polished feeding trails. Long used as a food source by Indigenous coastal communities, they remain a symbol of the Pacific intertidal zone’s quiet resilience, a living relic from a time before fish had even evolved jaws. Source: Oregon Public Broadcasting

6. Hermit Crabs – Southeast Atlantic & Gulf Coast

Hermit crabs are the ultimate beach scavengers, always on the move and always in search of better real estate. Unlike true crabs, their soft, spiraled abdomens lack a protective shell, so they borrow one, usually from an empty snail casing. Found under damp rocks, within tidepools, and in marshy areas from the Carolinas to the Gulf of Mexico, hermit crabs are easy to spot once you know what to look for: a mismatched shell, two tiny stalked eyes, and legs that never stop working. And when one finds a better shell? It’s not unusual to see a social “vacancy chain” form, where multiple crabs line up and swap homes in size order like awkward, armored roommates.

But these creatures aren’t just comical; they’re tough, strategic, and surprisingly social. Some species form small colonies and communicate with subtle antennal flicks or even claw drumming. They feed on detritus, algae, and the occasional small animal, helping keep coastal zones clean and nutrient-balanced. In many areas, especially on the Gulf Coast, they’re a common classroom pet or bait species. Still, their wild behaviors are far more nuanced. Hermit crabs even engage in shell battles, using their claws to tap or yank at an occupied shell to evict a current resident. With more than 800 species globally and several native to U.S. coasts, they’re proof that evolution favors the creatively resourceful. Source: Gulf Specimen

7. Limpets – Central & Northern California

Limpets are nature’s suction-cup survivalists, clinging so tightly to rocks that even crashing waves and curious fingers struggle to dislodge them. Found on the wave-battered coasts of Central and Northern California, these small, conical mollusks look like little gray or olive-colored hats attached to stone. But beneath their unassuming shell lies a muscular foot capable of creating an extraordinary vacuum seal, strong enough to resist predators and powerful surf. Some limpets return to the exact same spot on the rock, known as a “home scar,” grinding the surface to fit their shell perfectly and using chemical cues to find their way back with astonishing precision.

Though they move only a few inches per hour, limpets are tireless grazers. At high tide, they roam their rocky neighborhoods, scraping algae and microbial films off the surface with a rasping radula, a structure reinforced with iron to act like biological steel wool. Their feeding can shape the rock surface over time, leaving visible grazing tracks. Despite their sluggish lifestyle, limpets are ecological linchpins: they control algae growth, create habitat space for other organisms, and are a significant food source for sea stars and shorebirds. For something that looks like a pebble with a hat, the limpet is one of the hardest-working and hardest-sticking residents of the Pacific shoreline. Source: Limpets.org

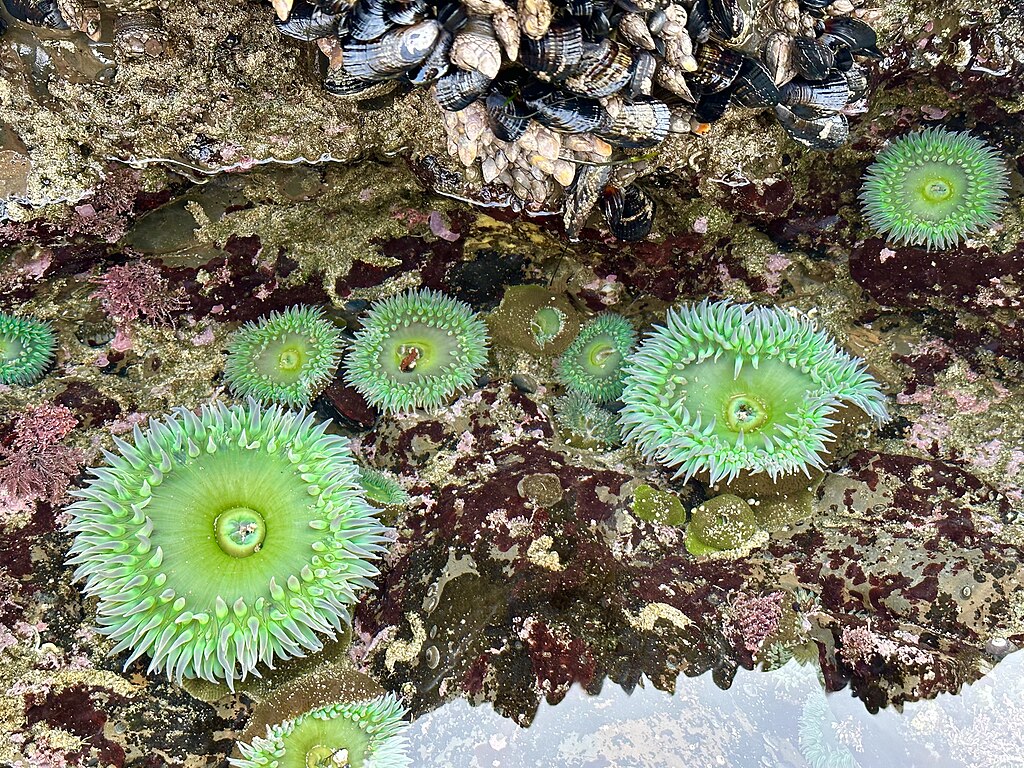

8. Sea Anemones – Pacific Northwest

Sea anemones are often mistaken for underwater flowers, but beneath their vibrant, petal-like tentacles lies a slow-motion predator armed with stingers and suction. Along the Pacific Northwest coast from the Olympic Peninsula to Oregon’s tidepools, these soft-bodied invertebrates attach to rocks, crevices, and pilings, waiting for unsuspecting prey to drift within reach. When a small fish or crab brushes past, the anemone’s tentacles fire off microscopic harpoons (called nematocysts), paralyzing the target before guiding it into a central, ever-hungry mouth. Despite their delicate appearance, many sea anemones are long-lived and incredibly tough; some can survive out of water for hours by sealing in moisture or pulling their tentacles inward like a clenched fist.

One of their strangest tricks? Cloning. Particular species can reproduce by splitting themselves in half, creating genetically identical colonies that completely blanket a tidepool. They also engage in territorial battles, using special stinging arms to fight off neighboring colonies like slow-motion jellyfish duels. Their tentacles contain green, pink, or blue pigments that fluoresce under UV light, and some even harbor symbiotic algae that provide additional energy through photosynthesis. As both predator and prey, sea anemones help maintain tidepool balance, anchoring an entire micro-ecosystem in place. Look closely under rocks at low tide; you might just see one slowly unfurling, like a flower blooming beneath the sea. Source: Oregon Marine Reserves

9. Barnacles – Atlantic & Pacific Coasts

Barnacles may look like tiny gray volcanoes glued to rocks and pier pilings, but they’re actually crustaceans, relatives of crabs and lobsters, that spend their adult lives cemented in place. Found from Maine to California, barnacles thrive in the harshest intertidal zones, enduring crashing waves, scorching sun, and the pounding of human feet. Their outer shell is made of overlapping calcium plates that protect a feathery feeding structure inside. When submerged, barnacles extend their cirri, delicate, comb-like appendages, into the water to filter plankton. It’s a graceful, rhythmic ballet performed by creatures that look like stone.

One of the most bizarre facts about barnacles? They possess the longest penis-to-body-size ratio in the animal kingdom, up to 8 times their own body length. This adaptation enables them to reproduce while remaining stationary, allowing them to reach neighboring barnacles during the spawning season. They’re also marvels of natural engineering: their underwater adhesive is so strong and water-resistant that scientists study it for medical and industrial applications. While barnacles can seem like a nuisance (especially to boats and docks), they play an important role in coastal ecosystems, providing habitat for tiny invertebrates and helping stabilize rock surfaces. Flip over a tide-washed boulder anywhere on the U.S. coast, and you’ll likely find a miniature metropolis of these tough, ancient survivors Source: Oceana

10. Ghost Shrimp – Gulf of Mexico

Ghost shrimp are the secret tunnelers of the Gulf Coast strange, pale crustaceans that spend nearly their entire lives underground. Unlike the translucent “glass shrimp,” these ghost shrimp are burrowers, living deep beneath sandy or muddy tidal flats from Texas to Florida. They build elaborate tunnel systems up to 3 feet below the surface, creating complex, Y-shaped burrows with multiple exits. These hidden architects play a huge role in their ecosystems by oxygenating sediment and redistributing nutrients, much like earthworms on land. Their long claws and slender, soft abdomens are specially adapted for digging through sand, though they occasionally venture out during low tide or after storms.

Despite their ghostly name, they’re surprisingly tough. The walls of their burrows are often reinforced with mucus to prevent collapse, and their entire body is built to stay hidden and out of reach of predators. Fishermen prize ghost shrimp as bait for species like redfish and pompano, and in some Gulf states, harvesting them is a regulated industry. Suppose you’re walking across a flat, damp beach and notice a bubbling hole or minor depression. In that case, chances are a ghost shrimp is lurking below, maintaining one of the most sophisticated construction projects in the intertidal world, entire neighborhoods of sand beneath your very feet. Source: National Park Service

11. Flatworms – Florida & Southern Coasts

Flatworms in the warm shallows of Florida and the southern Atlantic and Gulf coasts may be small, but they’re packed with surprises and sometimes a little scandal. These soft-bodied invertebrates are often no more than a few inches long, gliding like living ribbons under rocks, in seagrass beds, and along muddy estuaries. Their bodies are flat and undulating, allowing them to squeeze into impossibly tight crevices in search of food like protozoa, algae, or even smaller worms. Their colors range from brown or black to shimmering iridescent blues and purples, sometimes featuring intricate patterns that mimic more venomous animals, such as sea slugs.

One of the strangest facts about marine flatworms is their reproductive behavior. Many are simultaneous hermaphrodites, meaning each individual has both male and female organs. They engage in a bizarre form of mating known as “penis fencing,” where two flatworms duel with their sharp reproductive appendages to determine who gets to inseminate the other. The “loser” carries the fertilized eggs. It’s weird, it’s wonderfully wild, and it’s happening just below the surface at your favorite beachside tidepool. Though they lack specialized respiratory or circulatory systems, their thin bodies allow them to absorb oxygen directly through the skin. These simple creatures are a marvel of low-tech survival and a reminder that not all drama on the beach comes from the tourists.

12. Crayfish – Southeast Brackish Waters

Crayfish, also known as crawdads or mudbugs, are the clawed kings of Southern creeks, estuaries, and brackish backwaters. While they’re often associated with freshwater streams, many species thrive in the brackish zones where rivers meet the sea, especially in the Southeast. Under rocks or in submerged roots, you’ll find these armored invertebrates tucked into burrows or slowly scuttling across the bottom, scavenging decaying leaves, algae, or even small fish. Their lobster-like appearance isn’t just for show; they’re close relatives and share many of the same behaviors, including territorial battles and seasonal molting. Some Southeastern crayfish species even burrow vertically several feet into the mud to survive dry spells or tidal changes.

With over 300 species in North America alone, crayfish are a surprisingly diverse group, many of which are endemic to tiny geographic areas. They can regenerate lost claws several times over their lives and are a key link in both aquatic food chains and Southern culture, boiled, spiced, and served by the pound. But their ecological role goes deeper: crayfish aerate the soil, clean up detritus, and provide food for raccoons, fish, herons, and even otters. In some regions, their presence is a sign of good water health and ecosystem balance. Whether you’re flipping over a log in a Louisiana bayou or exploring a tidal marsh in Georgia, don’t be surprised if one of these mini-lobsters gives you a sideways stare.

13. Sea Urchins – California & Alaska

ea urchins are nature’s bristling landmines, spiny, slow-moving creatures that can turn a rocky shoreline into a prickly minefield. Along the Pacific coast from Southern California to the frigid waters of Alaska, you’ll find purple, red, and green urchins wedged between rocks or hidden under kelp fronds. Their bodies are covered in hundreds of spines that not only deter predators but also help them move, sense their surroundings, and even dig into crevices. Beneath those spines lies a set of five calcified “teeth” arranged in a structure called Aristotle’s Lantern, which they use to scrape algae from rocks or chew through kelp. Some species, like the red sea urchin, are exceptionally long-lived; scientists have found individuals estimated to be over 100 years old.

Despite their slow pace, sea urchins are ecosystem game-changers. When populations explode, especially in the absence of natural predators like sea otters, they can decimate entire kelp forests, creating what scientists call “urchin barrens,” rocky zones stripped of life. Yet, when kept in balance, urchins play a vital role in maintaining healthy underwater habitats. They’re also prized in culinary circles for their roe, known as uni, making them both ecologically and economically important. Divers seeking these spiny delicacies must handle them with care; urchin spines can puncture the skin and are notoriously hard to remove. So, if you’re exploring rocky tidepools or diving off the West Coast, watch your step; there’s a lot more going on beneath those spikes than meets the eye.

14. Tidepool Sculpins – Oregon & Washington

Tidepool sculpins are the secretive, darting shadows of the Pacific Northwest’s intertidal zones. Found in rocky tidepools from Oregon to Washington, these small, bottom-dwelling fish are masters of camouflage and quick escapes. They usually grow to just 2 to 4 inches long, with mottled brown, gray, or green coloring that matches the algae-covered rocks and barnacles around them. Their large, frog-like pectoral fins allow them to “hop” or perch on uneven surfaces, and their broad heads and bulging eyes give them a perpetually startled expression. But don’t be fooled; they’re territorial and scrappy, defending their pools fiercely from intruders, including other sculpins.

What makes tidepool sculpins especially remarkable is their ability to survive dramatic environmental swings. These hardy fish endure rapid changes in salinity, temperature, and oxygen levels as the tide goes in and out. They can even survive brief periods out of the water by absorbing oxygen through their moist skin and gills. During low tide, they often wedge themselves into cracks or under rocks to avoid predators and drying out. They feed on small crustaceans, worms, and mollusks and are a vital part of the tidepool food web. Though easy to overlook, sculpins are an evolutionary marvel: a fish that acts like a lizard, breathes like an amphibian, and lives in one of the most extreme habitats on Earth.

15. Rockweed Crabs – Maine

Rockweed crabs, also known as flat-clawed crabs, are the stealthy residents of Maine’s seaweed-strewn tidepools. These small, olive-green to brown crabs blend seamlessly into the thick mats of rockweed (a type of brown algae), making them incredibly hard to spot unless they move. Their flat, wide claws and low, rounded carapaces are perfectly adapted for slipping between fronds and wedging into crevices on the rocky shore. Typically measuring 1 to 2.5 inches across, they’re fast, cautious, and quick to retreat under cover at the slightest motion above.

Though easy to overlook, rockweed crabs are essential members of the coastal food web. They feed on small invertebrates, detritus, and algae and, in turn, serve as prey for seabirds, fish, and larger crabs. These crabs have a fascinating behavior known as tonic immobility—when threatened, they may “play dead” by going completely still to avoid detection. They’re especially abundant along the shores of Acadia National Park and other rocky coastal regions of Maine, where dense rockweed forests create perfect camouflage. Quiet and efficient, rockweed crabs are a reminder that even the most unassuming creatures play vital roles in coastal ecosystems.

16. Polychaete Worms – Gulf Coast & Atlantic

Polychaete worms may look like colorful centipedes from another planet. Still, they’re actually one of the most diverse and vital groups of marine invertebrates in the world. Found under rocks, within muddy sand flats, and clinging to pilings along both the Gulf Coast and Atlantic shores, these segmented worms range in size from less than an inch to over 3 feet long. Their bodies are lined with parapodia, fleshy appendages fringed with bristles that help them crawl, swim, and burrow. With over 10,000 known species globally, polychaetes come in wildly different forms: some are tube-dwellers that build elaborate mud chimneys, while others are flashy, free-swimming predators with protruding jaws.

Many polychaetes are also bioluminescent, lighting up with eerie blue or green glows when disturbed. Some emit clouds of glowing mucus or pulses of light as a form of communication or defense. Others, like the infamous fireworm, are venomous and can deliver painful stings through their brittle bristles. These worms play a crucial role in maintaining sediment health, oxygenation, and nutrient cycling, essentially serving as the marine equivalent of earthworms. Anglers often use particular species, like bloodworms and ragworms, as bait. Still, scientists also study polychaetes to gain a better understanding of ecosystem health and evolutionary biology. While they may never win a marine beauty contest, lift the right rock or dig into the right mudflat, and you’ll meet one of the ocean’s oldest and weirdest inhabitants.

17. Isopods – California & Florida

Isopods are like the armored roly-polies of the sea, flattened. These segmented creatures resemble something out of a sci-fi movie. Along the rocky tidepools of California and the sandy shores of Florida, marine isopods can be found hiding beneath stones, tucked into kelp holdfasts, or burrowing in the sand. Most are small, measuring under an inch in length, with rigid, overlapping plates that protect them from predators and desiccation. They move with a mechanical grace, scuttling sideways or backward when disturbed. Though not flashy, they are adamant: able to survive dramatic swings in temperature, salinity, and oxygen levels, all while scavenging for decaying material and detritus.

Some species are parasitic, attaching themselves to the gills or tongues of fish and feeding on their blood, a disturbing but fascinating survival strategy. Others, like their infamous deep-sea cousins, the giant isopods, can grow over 16 inches long and survive for years without food. On land, their relatives are common in garden soil. Still, in coastal ecosystems, marine isopods play a crucial role in cleanup, helping to break down organic debris and maintain balance in tidepool systems. Their armored bodies and ancient lineage make them miniature relics of evolutionary endurance. Flip over a coastal rock and spot one? You’re face to face with a survivor that’s barely changed in hundreds of millions of years.

18. Periwinkles – East Coast, Especially Maine

Periwinkles are the tiny but tenacious snails carpeting the rocky intertidal zones of the East Coast, especially in Maine, where they’ve practically become part of the shoreline’s texture. These little mollusks, rarely more than an inch long, sport tightly coiled, conical shells that range from slate gray to brownish-black. Though they look delicate, they’re anything. Still, periwinkles are incredibly hardy, able to survive out of water for extended periods by sealing off their shells with a tight “operculum,” a trapdoor-like structure that keeps in moisture. They’re often found in massive clusters under rocks, in crevices, or even attached to each other, forming dense living carpets that crunch underfoot at low tide.

But periwinkles are more than just tidepool filler; they’re powerful grazers that reshape their environments. With their rasping radula, they scrape algae and diatoms from rocks with a grinding efficiency that can alter entire intertidal communities. Originally native to Europe, the common periwinkle was likely introduced to North America in the 1800s and quickly became a dominant species, outcompeting native snails and spreading across thousands of miles of coastline. A single female can lay thousands of eggs in one season, which helps explain their overwhelming abundance. In Maine, they’re also a small-scale delicacy, sometimes harvested and boiled like their larger sea snail cousins. If you’ve ever wandered a tidepool and heard the faintest crunch, chances are you’ve just stepped into a periwinkle metropolis.

19. Sea Stars – Northern California & Puget Sound

Sea stars, commonly but mistakenly called starfish, are among the most iconic and alien-looking creatures hiding beneath coastal rocks. Along the tidepools of Northern California and Puget Sound, they come in a dazzling variety of colors, from deep purple and vibrant orange to speckled reds and pinks. These echinoderms aren’t just eye-catching; they’re fierce predators. Using rows of tiny tube feet located on the underside of their arms, they slowly glide over rocks and latch onto prey like mussels, barnacles, and clams. Then, in one of the ocean’s most bizarre feeding techniques, they actually evert their stomachs outside their bodies to digest food externally before pulling the slurry back in.

Some species, like the ochre sea star, are considered keystone species, meaning their presence (or absence) can completely restructure an ecosystem. If sea stars are removed from a tidepool, mussel populations can explode, outcompeting dozens of other species. After a devastating outbreak of sea star wasting syndrome in the 2010s, which caused populations to crash across the Pacific coast, researchers began to understand just how critical these animals are. Remarkably, many are now making a slow comeback. Sea stars can regenerate lost arms, and some species can even regrow an entire body from a single severed limb. They’re a perfect mix of beauty, strangeness, and resilience, an essential part of the coastal puzzle that you’re lucky to spot under the right rock at low tide.

20. Peanut Worms – Louisiana & Gulf Estuaries

Peanut worms, or sipunculids, are some of the oddest animals you’ll ever see unless you know exactly where (and how) to look. These soft-bodied, unsegmented worms live buried in the muddy sands of Gulf Coast estuaries, particularly in Louisiana’s deltaic marshes, and are experts at staying hidden. Shaped like short, rubbery tubes with a retractable feeding proboscis, they earn their name because their bodies contract into a peanut-like shape when disturbed. Most species measure just 2 to 4 inches long, though some can stretch up to 18 inches, especially when fully extended while feeding.

Despite their unassuming looks, peanut worms play a crucial role in sediment ecosystems. They burrow deep into the seafloor, constantly churning and aerating the mud as they go, improving oxygen flow and nutrient cycling in a way similar to earthworms on land. These animals feed by extending their proboscis to sweep up detritus and organic particles, helping to break down material that would otherwise stagnate. They have no circulatory or respiratory systems; instead, gas exchange happens through their moist skin. In some areas, fishers use them as bait, and scientists study their ancient body plans to gain a better understanding of early animal evolution. Flip a chunk of estuary mud in southern Louisiana, and you just might uncover one of the most primitive and essential builders of the soft-bottom marine world.

21. Glass Shrimp – Gulf Coast Marshes

Glass shrimp are the translucent phantoms of Gulf Coast marshes. These nearly invisible crustaceans glide through brackish waters like moving shadows. Also known as grass shrimp, these delicate creatures are almost entirely see-through, save for their black eyes and faint internal organs. Found hiding among submerged grasses, oyster beds, and under rocks in tidal creeks and estuaries, they typically measure 1 to 2 inches long. Their near-invisibility isn’t just a quirk; it’s an evolutionary survival tactic that helps them avoid the gaze of hungry fish and wading birds. When threatened, they dart backward in rapid bursts using their powerful tails, disappearing into the murky shallows almost instantly.

Glass shrimp are vital to coastal ecosystems, serving as both prey and a cleanup crew. They feed on algae, detritus, and small organisms in the water, helping to maintain balance in marsh systems. Because of their sensitivity to pollution and environmental shifts, they’re also used in water quality assessments by researchers. In Louisiana, Texas, and Florida, they’re often scooped up as bait by anglers targeting speckled trout or flounder. But what’s frequently overlooked is their role in the invisible web of marsh life, connecting grasses, sediments, fish, and birds through a daily cycle of filtering and foraging. To find them, crouch near the edge of a marsh and look carefully. Sometimes, the most important animals are the ones you can barely see.

22. Blood Worms – Mid-Atlantic Coast

Blood worms may sound like something from a horror film, and they kind of are, at least if you’re a small fish or unlucky clam. Found burrowed deep in the mudflats of the Mid-Atlantic Coast, especially in estuaries and salt marshes, these pale pink, segmented worms are packed with hemoglobin, which allows them to thrive in low-oxygen environments and gives them their eerie red hue. Ranging from 4 to 14 inches long, blood worms have powerful jaws that shoot out from a proboscis and are tipped with copper, a rare and fascinating biological adaptation. When feeding or defending themselves, they can strike with surprising speed and bite hard enough to draw blood from a human finger.

These worms are prized bait for striped bass, flounder, and other coastal game fish, making them a commercial staple in places like Maine, where they’re harvested and shipped across the East Coast. But their role in marine ecosystems runs deeper: they aerate sediments, cycle nutrients, and feed a wide range of predators, including crabs, eels, and birds. Their copper-infused jaws are so unique that scientists study them for insights into biomaterials and synthetic teeth. If you’re brave enough to dig through marsh muck or tidal flats, you might unearth one and discover a creature that looks more alien than Earth-born.

23. Oyster Toadfish – Chesapeake Bay & Southeast

The oyster toadfish is the grumpy bulldog of the coastal shallows, a broad-headed, wide-mouthed fish that growls (yes, growls) when disturbed. Found lurking beneath rocks, oyster beds, and dock pilings along the Chesapeake Bay and down through the Southeast coast, this bottom-dweller is often called “ugly” thanks to its warty skin, bulging eyes, and flattened body. But what it lacks in looks, it makes up for in survival skills. Toadfish are ambush predators, lying in wait for shrimp, crabs, and small fish to wander by before lunging with lightning speed. Their jaws are powerful enough to crush shellfish, and their thick skin helps them withstand cuts and abrasions from rocky hideouts.

What really sets them apart is their sound. Male oyster toadfish produce a deep, vibrating “boat whistle” call during mating season, loud enough to be heard through a hull, which once caused problems for Navy sonar equipment. They’re also one of the few fish that can survive in low-oxygen, high-pollution environments, making them demanding customers in some of the most challenging estuarine habitats. While often overlooked in favor of more glamorous fish, toadfish are essential predators in oyster reef ecosystems. They are sometimes caught incidentally by anglers (who are frequently startled by their croaky protests). If you ever flip a rock in brackish waters and hear a low grunt, you’ve just met the bay’s most vocal and unbothered resident.

24. Clingfish – Southern California

Clingfish are the stealthy suction artists of Southern California’s tidepools, small, squishy fish that defy gravity by sticking to almost anything. Measuring just 1 to 3 inches long, these flattened, teardrop-shaped fish use a special pelvic disc (a modified version of their fins) to cling to rocks, kelp, sea urchins, and even the shells of larger animals. Found in rocky intertidal zones from Santa Barbara down to San Diego, clingfish can ride out crashing waves, shifting tides, and even vertical surfaces without being swept away. Their colors often match their surroundings, speckled browns, pale grays, or mossy greens, making them nearly invisible until they scoot away with a sudden wiggle.

What makes clingfish especially intriguing is how strong their suction actually is. Recent studies have found that their adhesive discs can outperform commercial suction cups, sticking securely even on rough, wet surfaces. Engineers have begun studying clingfish to design better biomedical adhesives for human use. Despite their strength, clingfish are gentle grazers, feeding on tiny crustaceans, algae, and biofilm. They often live in close quarters with other tidepool creatures, taking shelter in sea urchin spines or empty barnacle shells. They’re rarely seen unless you lift the right rock at just the right moment, and even then, they’ll likely vanish in a blink. As the final surprise on your coastal scavenger hunt, clingfish prove that some of the ocean’s most impressive tricks come in its smallest, stickiest packages.

What’s Beneath the Rocks Might Blow Your Mind

Next time you stroll along a tidepool, dig your toes into marshy sand or flip over a barnacle-covered rock, remember: you’re walking across a hidden frontier. Beneath the surface, an entire world thrives, crawling, clinging, burrowing, and blinking underfoot. From ghostly shrimp in the Gulf to suction-clad clingfish in Southern California, these small but mighty creatures keep coastal ecosystems running like clockwork. Some are ancient relics, others brilliant adapters, and a few appear to belong on another planet entirely. But each one plays a role in the delicate balance of life between land and sea. All it takes to witness their strange, fascinating lives is a moment of curiosity and the willingness to get a little sandy.

The story What’s Hiding Under Rocks on U.S. Beaches? 24 Wild Finds, Region by Region was first published on DailyFetch.