These creatures thrive in total darkness using bizarre survival systems.

Most life on Earth depends on the sun, but not these. Deep beneath the ocean, sealed in pitch-black caves, or buried miles below the surface, these bizarre organisms have evolved to survive in complete darkness. No photosynthesis, light cues, day-night cycles, just an eerie world powered by chemical reactions, blind instincts, and evolutionary oddities. From translucent predators to bacteria that “eat” rocks, these creatures rewrite everything we thought we knew about survival. Their alien adaptations aren’t just creepy; they may also hold clues to the origins of life on other planets.

1. Yeti Crab

Discovered only in 2005, the Yeti crab (Kiwa hirsuta) looks like something straight out of a myth. Found near hydrothermal vents 7,200 feet deep in the South Pacific, this blind crustacean is covered in long, hair-like bristles that resemble fur. But those “hairs” serve a far stranger purpose than warmth; they house colonies of bacteria that help the crab survive. The Yeti crab waves its claws in the mineral-rich water spewing from nearby vents, feeding the bacteria that live on them. In return, the crab eats the bacteria or benefits from their detoxifying powers: no sunlight, no plants, just a bizarre chemosynthetic survival loop.

The Yeti crab’s fuzzy appearance and alien habitat made it an instant icon of deep-sea biology. Scientists believe its bristle-farming strategy is a form of symbiosis seen nowhere else on Earth. And while it may look fragile, this crab thrives in scalding water, crushing pressure, and zero light. Some species, like Kiwa puravida, even dance their limbs back and forth to boost bacterial growth, like farming microbes with a waltz. It’s proof that when sunlight disappears, evolution gets weird in the best way. Source: Ocean Conservancy

2. Olm

The Olm is a pale, blind salamander that haunts the pitch-black limestone caves of the Dinaric Alps in the Balkans. With skin so translucent it glows faintly pink, and eyes buried beneath its skin, the Olm looks like a ghost frozen in a slow-motion swim. It’s entirely aquatic, living in frigid, oxygen-poor underground rivers where few animals dare tread. With no need for vision, the Olm evolved an acute sense of smell and vibration detection to hunt tiny insects and crustaceans. Its metabolism is so slow that it can survive up to 10 years without food, and some individuals live for over a century.

Scientists believe the Olm’s unique traits may help us understand extreme longevity and metabolic regulation. Because it never sees sunlight, it lacks pigment and produces unusual proteins to protect its DNA from stress. It even retains juvenile features like external gills into adulthood, a condition called neoteny. Often referred to as a “baby dragon” in local folklore, the Olm’s eerie presence and bizarre biology have made it a symbol of subterranean life at its strangest. Source: Wikipedia

3. Giant Tube Worm

Found in the darkest depths of the Pacific Ocean near hydrothermal vents, the giant tube worm (Riftia pachyptila) is a marvel of survival without sunlight. These eerie, blood-red-tipped creatures can grow over 8 feet long and live in colonies that look like alien forests. They lack mouths, eyes, or stomachs. Instead, they rely on a symbiotic relationship with bacteria that live inside their bodies. These bacteria convert hydrogen sulfide from vent water into organic molecules, effectively feeding the worm through a process called chemosynthesis. It’s one of the only ecosystems on Earth where life doesn’t trace back to photosynthesis.

Despite existing in temperatures between near freezing and over 140°F, these worms thrive in an environment saturated with toxic chemicals and crushing pressure. Their blood contains a special hemoglobin that binds oxygen and hydrogen sulfide, enabling them to extract vital gases from vent water simultaneously. First discovered in 1977 during an expedition near the Galápagos Rift, the giant tube worm completely upended scientists’ assumptions about where and how life could exist. It’s now seen as a model organism for studying life on other planets or moons like Europa. Source: Smithsonian Ocean

4. Texas Blind Salamander

The Texas blind salamander (Eurycea rathbuni) lives in the sunless aquifers beneath San Marcos, Texas. With feathery red external gills and skin as pale as porcelain, this amphibian looks more like a ghost than a living creature. It’s completely blind, its eyes are reduced to dark spots beneath its skin, and it relies on motion and chemical cues to hunt tiny prey like shrimp and snails in total darkness. Because these salamanders live in isolated, groundwater-fed cave systems, they’ve adapted to a low-energy lifestyle, moving slowly and feeding opportunistically.

Remarkable is how specialized this creature has become to its shadowy, underground world. Scientists believe the Texas blind salamander has lived in isolation for millions of years, evolving independently from its surface-dwelling relatives. Its gills allow it to absorb oxygen from the water without needing to surface, and its sensitivity to vibrations lets it detect even the slightest movement in the water. It’s also a powerful indicator species; any contamination in the Edwards Aquifer occurs in their fragile populations first. This makes the Texas blind salamander a key figure in conservation efforts across central Texas. Source: US Fish & Wildlife Service

5. Devil Worm

The Devil Worm (Halicephalobus mephisto) is one of the deepest-living multicellular organisms ever discovered. It is found over 2.2 miles beneath the Earth’s surface in South African gold mines. Barely half a millimeter long, this microscopic nematode survives in hot, high-pressure water-filled rock fractures where temperatures soar above 100°F and oxygen levels are near zero. Named after Mephistopheles, a demon from German folklore, the Devil Worm thrives in extremely extreme conditions once thought to be uninhabitable for complex life.

What makes the Devil Worm remarkable is its ability to survive in complete isolation from the surface world. Its DNA shows unique adaptations for heat shock and stress resistance, and it appears to have descended from surface worms that somehow found their way deep underground and evolved in place. Its existence has significant implications for our understanding of life’s resilience, especially in the search for life on other planets or moons with subsurface oceans, like Europa or Enceladus. The discovery rewrote the known limits of animal life and opened new doors to studying extremophiles. Source: National Geographic

6. Cave Angel Fish

The Cave Angel Fish (Cryptotora thamicola) is a tiny, translucent wonder that defies almost every assumption about fish anatomy. Native to the caves of northern Thailand, this rare species not only lives in complete darkness but also walks, yes, walks along the cave walls and waterfalls using a unique, four-limbed gait. It’s the only known fish with a pelvic structure and muscle attachments resembling those of land vertebrates, allowing it to climb vertical rock surfaces in flowing water. It’s completely blind, feeding off the sparse organic matter that drifts through its lightless, underground home.

Discovered in 1985 and first studied in detail in the 2000s, the Cave Angel Fish’s locomotive abilities stunned scientists. It bridges the gap between aquatic and terrestrial movement and explains how the first land animals might have transitioned from water. Its specialized joints and robust pelvic girdle are more similar to salamanders than to typical fish. Living in swift, crashing currents deep within limestone cave systems, it has evolved to survive and thrive where few vertebrates dare. It’s an evolutionary ghost, gliding between worlds in total darkness. Source: Sci News

7. Blind Cave Beetle

Hidden deep in the karst caves of Slovenia and Croatia, the blind cave beetle (Leptodirus hochenwartii) is one of the earliest described true cave-dwelling species. First discovered in 1831, this beetle was such a strange find that it helped launch the entire field of biospeleology, studying life in caves. Its elongated body, paper-thin exoskeleton, and lack of eyes make it a textbook example of troglomorphism, the suite of traits animals develop to adapt to permanent darkness. It survives on organic debris, fungi, and the occasional insect carcass that drifts into the cave ecosystem.

What’s fascinating about this beetle is how extreme its adaptations are. Its antennae are hyper-sensitive, compensating for its total blindness by detecting changes in airflow and moisture. It moves slowly, conserves energy, and can go months without food. Researchers believe the species has remained unchanged for millions of years, living in stable cave environments where evolution takes a different, almost frozen path. The blind cave beetle isn’t just a curiosity; it’s a relic from another time, surviving in silent darkness with eerie precision. Source: National Institute of Health

8. Mexican Tetra

The Mexican tetra (Astyanax mexicanus) is one of nature’s most intriguing dual citizens. It exists in two forms: one that lives in rivers and has eyes, and another that has adapted to life in pitch-black caves by losing them entirely. The cave-dwelling version, often found in the limestone systems of northeastern Mexico, is completely blind and lacks pigmentation, appearing ghostly pale. Over generations, enhanced taste buds and lateral line sensors have evolved to navigate and hunt in total darkness. While its surface relatives rely on vision, the cave form uses vibrations and water pressure changes to locate prey.

The cave Mexican tetra is so scientifically valuable because it’s one of the only animals where researchers can directly compare surface and cave evolution within the same species. Scientists have studied how specific genes deactivate the eye structures during early development, explaining how evolutionary pressure shapes anatomy. Even more fascinating, when cave and surface fish interbreed, their offspring sometimes develop partially formed eyes, revealing just how plastic evolution can be. This fish is more than a curiosity; it’s a living laboratory of adaptation. Source: New Scientist

9. Remipede

Remipedes are blind, pale crustaceans that live exclusively in coastal anchialine caves and landlocked pools connected to the sea, mainly in the Bahamas, the Canary Islands, and Australia. They look like centipedes but swim with dozens of paddle-like limbs, gliding silently through subterranean saltwater tunnels. Discovered only in 1979, remipedes are among the most primitive crustaceans alive today and are considered living fossils. Despite their soft, translucent bodies and total blindness, they’re top predators in their pitch-black ecosystem, using venom to paralyze and digest prey, an extremely rare trait among crustaceans.

What sets remipedes apart is their combination of ancient lineage and highly adapted behavior. They possess a brain structure strikingly similar to that of insects, which has fascinated neurobiologists studying the evolution of arthropods. Their venomous fangs can break down flesh before digestion, similar to spiders, an unusual and advanced trait for such a visually simplistic creature. Remipedes thrive where sunlight can never reach, using chemical and sensory cues to locate their prey in underwater labyrinths. They’re eerie, elegant reminders that nature never stops innovating even in the deepest dark. Source: National Geographic

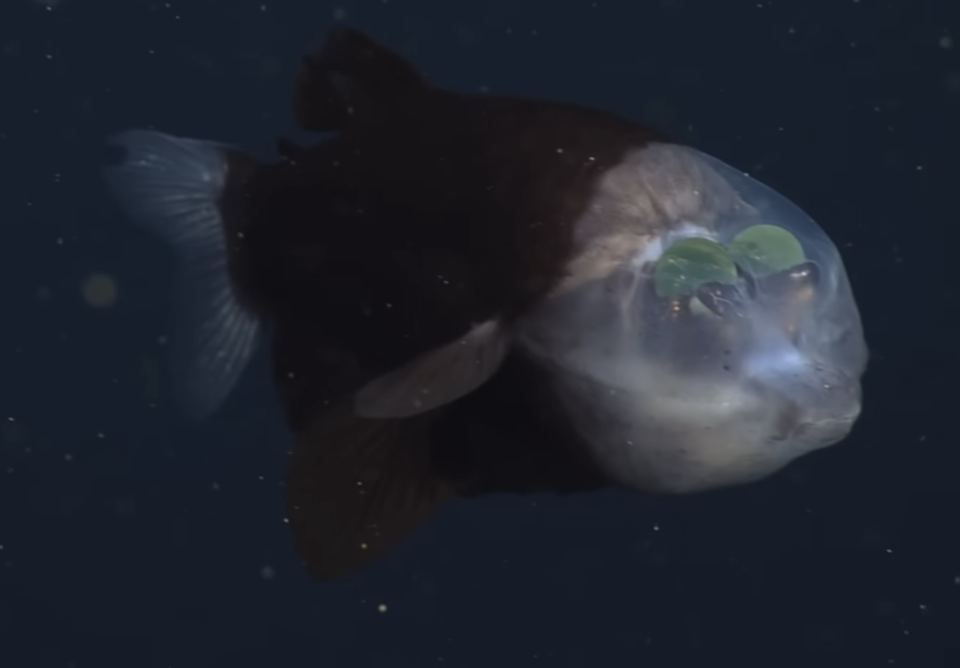

10. Barreleye Fish

The barreleye fish (Macropinna microstoma) is a deep-sea oddity with a completely transparent head and tubular, upward-facing eyes that can rotate inside its skull. Found at depths between 2,000 and 2,600 feet off the coasts of the Pacific, this fish lives in the twilight zone too deep for sunlight to penetrate fully, yet not quite as dark as the ocean’s abyssal depths. Its fluid-filled, see-through dome allows it to collect the faintest glimmers of bioluminescence from prey above. Meanwhile, its glowing green eyes can swivel forward when it needs to grab food drifting toward its mouth.

Discovered in the 1930s but only observed alive in 2004, the barreleye was a long-standing mystery due to its bizarre anatomy and elusive behavior. Its ability to rotate its eyes separately from its head gives it a unique edge in locating prey like siphonophores and jellies. The transparent shield protects its sensitive eyes while filtering light to focus only on bioluminescent flashes. It’s an evolutionary solution to a world of nearly total darkness using clarity, not color, to see the unseen. Source: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI)

11. Cave Spider

Often called the “orb-weaver of the underworld,” Meta menardi is a large, long-legged spider that dwells in the twilight and dark zones of caves across Europe and parts of Asia. While juveniles venture toward cave mouths, adults spend their entire lives deep inside, without sunlight or airflow. These spiders don’t spin classic sticky webs to catch prey; they hang motionless in crevices or ceilings and pounce on cave crickets, beetles, and other arthropods using vibration as their guide. With poor eyesight and a reliance on mechanosensory hairs, they’ve become masters of silent ambush in pitch black.

What’s particularly creepy-fascinating about Meta Menardi is how it’s adapted to the rhythm of a world without day or night. Its internal clock runs on an unusually long circadian rhythm, unlinked from sunlight. Eggs are suspended in silky sacs that dangle from cave ceilings for up to a year before hatching, a slow-motion lifecycle shaped by the stable, dark environment. While rarely seen, these spiders are crucial predators in subterranean ecosystems, keeping cave insect populations in check. They’re eerie, elegant, and perfectly at home in the dark. Source: British Arachnological Society

12. Horomonas radiovorans

Horomonas radiovorans is a truly extreme survivor; this single-celled bacterium doesn’t just live without sunlight, it thrives in places most life would consider death zones. Deep in radioactive waste dumps and subsurface rock layers, it can feed on energy released by radioactive decay. This microbe doesn’t photosynthesize or rely on organic carbon. Instead, it extracts electrons from radioactive elements like uranium and thorium, using them to fuel its cellular processes. That means it can survive in absolute darkness, with no oxygen, no light, and levels of radiation that would kill a human in minutes.

Horomonas radiovorans’ potential for cleaning up nuclear waste sites is particularly fascinating. Thanks to special DNA-repair enzymes and protective proteins, its radiation resistance is off the charts. Some scientists believe it could help terraform other planets or provide insight into how life might exist beneath the surface of Mars. It’s not flashy, and you’ll never see it without a microscope, but this bacterium might be one of the toughest creatures on Earth in the strange realm of life without light. Source: Nature Reviews Microbiology

13. Velvet Worm

The velvet worm might look cute and slow, but it’s one of the most bizarre ambush predators in the invertebrate world, and some species live in tropical caves and mossy crevices where sunlight never reaches. Peripatus solorzanoi, the largest velvet worm ever discovered, reaches lengths of nearly 8 inches and inhabits dark, moist environments in Costa Rica’s forest caves. With tiny eyes, antennae, and clawed legs, it sneaks up on prey like insects or termites and attacks using something truly weird: a rapid-fire slime cannon.

The velvet worm sprays a sticky jet of glue from glands just above its mouth, immobilizing its target within a split second. Then it injects digestive saliva to liquefy its prey and slurps it through a straw-like mouth. With its soft, segmented body, slow, deliberate movement, and prehistoric lineage dating back 500 million years, this creature is a living relic. Its hunting style is so unique that scientists have studied it to inspire bio-adhesive technologies, making it one of the strangest and most influential animals you’ve never seen. Source: BBC Earth

14. Vampire Squid

Despite its spooky name, the vampire squid (Vampyroteuthis infernalis) isn’t a bloodsucker; it’s a deep-sea cephalopod that lives more than 3,000 feet below the surface in oxygen-deprived zones where most marine animals can’t survive. Its name, “vampire squid from hell,” comes from its dark, cloak-like webbing and glowing blue eyes that shimmer in total blackness. Unlike traditional squid or octopuses, it doesn’t actively hunt. Instead, it floats passively, feeding on “marine snow,” a drift of decomposing matter, fecal pellets, and microscopic debris falling from above.

What makes the vampire squid so relatable is its low-effort, high-survival strategy. It uses the least energy possible, rarely moves fast, and doesn’t need much oxygen—a perfect example of deep-sea minimalism. When threatened, it doesn’t squirt ink but releases a bioluminescent cloud of mucus filled with glowing particles to distract predators. It’s soft-bodied, flexible, and adapted to a world of scarce light, food, and oxygen. Think of it as the ultimate introvert of the ocean, low drama, high weirdness, and perfectly content in the quiet dark. Source: Monterey Bay Aquarium

15. Ice Worm

The ice worm (Mesenchytraeus solifugus) sounds made-up, but it’s very real and weird. These tiny, black, thread-like worms live their entire lives in the glacial ice of the Pacific Northwest and Alaska, wriggling just below the surface of snowfields and ice sheets. They only come out at dusk or dawn, when the light is lowest and temperatures are just right, around 32°F. They melt if they’re exposed to direct sunlight or temperatures above freezing for too long. Ice worms eat snow algae and microscopic bacteria, living in near-constant cold and near-total darkness.

What makes them surprisingly relatable is their obsession with comfort zones, too much heat, light, or change, and they’re toast (literally). They don’t hibernate, don’t migrate, and don’t evolve quickly. Instead, they’ve carved out a hyper-specific niche and cling to it with slow, glacial precision. They even follow circadian rhythms despite never seeing the sun, suggesting internal clocks are hardwired into life. In a world where adaptability is everything, the ice worm reminds us there’s power in knowing exactly what works for you and refusing to budge. Source: University of Alaska Fairbanks

16. Naked Mole Rat

The naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) is a pink, wrinkled, nearly hairless rodent that lives in sprawling underground colonies beneath the arid deserts of East Africa. These bizarre mammals spend their entire lives in darkness, burrowing through soil with their oversized teeth and navigating by touch and scent. Their eyes are nearly useless, and instead of relying on vision, they communicate using chirps and squeaks while using sensitive whiskers to find their way. They live in a social structure more like ants or bees than mammals, with a queen, workers, and even soldier mole rats guarding the tunnels.

What makes naked mole rats oddly relatable is how they lean into community and specialization. Every mole rat has a role, and they thrive in close quarters, working together to survive heat, hunger, and claustrophobic conditions. They’re also super-resilient: they can survive 18 minutes without oxygen, are nearly immune to cancer, and feel almost no pain in their skin. They might look like little alien hot dogs, but their cooperative, no-light lifestyle is a testament to teamwork and thriving in a world built entirely on touch, scent, and trust. Source: Smithsonian’s National Zoo

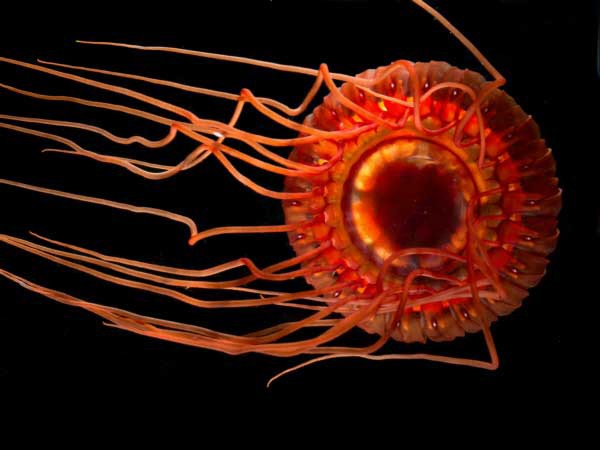

17. Atolla Jellyfish

The Atolla jellyfish (Atolla wyvillei) is a deep-sea drifter that lives in the ocean’s midnight zone, typically between 3,000 and 13,000 feet down, where no sunlight ever reaches. With its ruby-red body and long, lashing tentacles, it resembles something from a science fiction film. But its real claim to fame is how it handles danger. When attacked, the Atolla jellyfish produces an intense bioluminescent display known as a “burglar alarm,” a sudden burst of glowing light that attracts even bigger predators to scare off its attacker. It’s like pulling the fire alarm in the dark, hoping someone else takes care of the threat.

Despite its flashy defense, this jellyfish lives a slow, ghostlike existence. It floats through frigid water, feeding on marine snow and tiny creatures with its sticky tentacles. Its red coloration renders it nearly invisible at these depths, since red wavelengths don’t penetrate deep water. It doesn’t have eyes or a brain as we know them, but it thrives by sensing vibrations and light changes in its environment. The Atolla jellyfish isn’t just surviving in the deep; it’s turning darkness into its greatest weapon. Source: MBARI

18. Blind Cave Crayfish

The blind cave crayfish is a pale, eyeless freshwater crustacean that lives deep in limestone caves throughout Alabama, Tennessee, and Georgia. It is about 2 inches long and looks like a ghostly miniature lobster, translucent, slow-moving, and eerily calm. These crayfish navigate pitch-black underground streams using their antennae and fine-tuned touch receptors. They’ve adapted to a low-energy lifestyle with almost no food sources available, moving infrequently and metabolizing slowly. Some individuals have been observed living over 15 years, unusually long for such a small invertebrate.

What makes the blind cave crayfish relatable is its extreme efficiency. It doesn’t waste a thing in a world of total darkness and limited resources. Every twitch, every movement, is measured. It doesn’t seek out new territory or rush to eat; it simply endures, navigating its timeless underground maze with quiet determination. It’s an introvert’s dream: dark, calm, and pressure-free. Scientists study these crayfish to better understand cave ecology and the long-term effects on evolution and aging. Source: Encyclopedia of Life

19. Goblin Shark

The goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) is a deep-sea relic that looks more like a monster from the past than a modern fish. Living at depths of 3,000 to 4,000 feet, far below where sunlight can penetrate, this “living fossil” hasn’t changed much in over 125 million years. With its elongated, flattened snout and terrifying jaw that shoots forward like a spring-loaded trap, the goblin shark is built for ambush in the pitch black. It doesn’t chase prey. Instead, it detects faint electrical signals from fish and squid, then launches its extendable jaw to snatch them at lightning speed.

Despite its nightmarish looks, the goblin shark is a slow-moving, soft-bodied creature, more ghost than hunter. Its pinkish-gray hue isn’t for camouflage, but the result of its translucent skin stretched over visible blood vessels. Because it lives so deep, it’s rarely seen alive, and most of what we know comes from deep-sea trawls or occasional sub sightings. It’s proof that strange and ancient life is still lurking in the lightless corners of Earth’s oceans, quietly surviving while the rest of the world forgets it ever existed. Source: NOAA Teacher at Sea Blog

20. Pompeii Worm

The Pompeii worm (Alvinella pompejana) is one of the most heat-tolerant animals on Earth, living on the walls of hydrothermal vents more than 8,000 feet below the ocean surface. These vents gush scalding, mineral-rich water reaching temperatures up to 750°F, yet the worm clings to this environment with its feathery gills waving in the current. What keeps it alive? A thick layer of symbiotic bacteria on its back that insulates it from the heat and helps process toxic chemicals. With a head in cool water and a tail in near-boiling temperatures, it survives on a razor-thin line between extremes.

The Pompeii worm doesn’t just tolerate heat, it thrives in complete darkness, intense pressure, and an atmosphere full of sulfur and heavy metals. It was first discovered in the 1980s by a deep-diving submersible, and scientists have since studied its remarkable tolerance to understand how life can exist in such hellish places. It explains how early life might have started in Earth’s oceans and how life could survive on other planets with volcanic activity beneath ice. This worm is pure resilience in a world with no light and no mercy. Source: Deep Sea News

21. Parasitic Eyeless Flatworm

This parasitic flatworm lives in total darkness inside underground aquifers and cave streams, particularly in Eastern Europe. Unlike its light-dwelling relatives, Gyrodactylus subterraneus has no eyes, no pigment, and no need for visual navigation. It attaches itself to blind cavefish and amphibians, feeding on their skin and mucus. These worms reproduce via polyembryony, where offspring develop inside the mother’s body, already pregnant with their own young, a Matryoshka doll of parasites. They never need to leave their host’s lightless habitat, and they spread without ever being seen.

What makes this worm fascinating and a little unsettling is its evolutionary minimalism. It’s stripped away everything unnecessary: sight, color, even external reproduction. It lives off others so efficiently and subtly that it often goes unnoticed even in scientific surveys. It’s one of the dominant lifeforms in some caves, quietly thriving in total obscurity. It’s the ultimate freeloading survivor, perfectly adapted to take advantage of organisms already adapted to darkness. Source: Fish Pathogens

22. Japanese Spider Crab (Deep-Sea Variant)

The Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi) is the largest arthropod in the world, with legs that can stretch over 12 feet from claw to claw. While many live in shallower coastal waters, the older and larger individuals migrate down into the abyss, sometimes to depths exceeding 1,800 feet, where sunlight can no longer penetrate. Down here, in the pitch-black trenches of the Pacific, these crabs become slow-moving giants, feeding on dead animals, algae, and anything that drifts to the seafloor. Despite their size, they’re gentle scavengers, not aggressive hunters.

What makes the deep-sea spider crab so fascinating is how ancient and alien it feels, yet it’s a crustacean cousin of common crabs seen at seafood markets. Their slow metabolism and ability to go long without food make them well-suited to life in the dark. As they age, they grow more rigid and resilient, their long legs creeping silently across underwater plains like something out of a myth. Seeing one of these gentle giants emerge from the shadows of the deep is equal parts eerie and mesmerizing. Source: Monterey Bay Aquarium

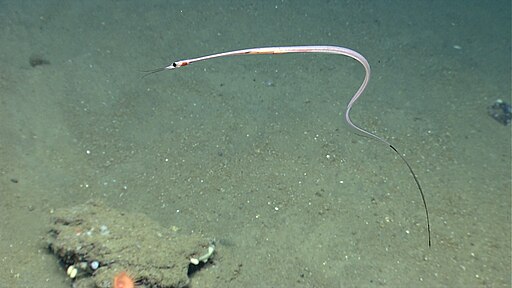

23. Snipe Eel

The snipe eel (Nemichthys scolopaceus) is a long, thread-thin predator drifts through the ocean’s midnight zone at depths between 3,000 and 6,000 feet. With a body that can stretch up to 5 feet but only a few inches wide, it looks like a floating ribbon. Its most bizarre feature is its beak-like jaw, curved and loosely hinged, lined with tiny hooked teeth that help it snatch plankton and shrimp in the dark. The jaw tips don’t even touch, allowing it to “comb” through the water like a filter, scooping up prey without needing a chase.

Despite its alien appearance, the snipe eel’s elegance and efficiency make it strangely relatable. It’s not a powerhouse predator; it survives by being subtle, light, and tuned to its environment. Its slow-motion swimming, delicate frame, and minimalist energy use are perfect for the deep ocean’s cold, silent world. Scientists still aren’t sure how it mates or where it spawns, adding to its mystery. But one thing’s sure: in a place where sunlight has never touched, the snipe eel has found a way to move like a ghost and live like a whisper. Source: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI)

24. Giant Isopod

The giant isopod (Bathynomus giganteus) is the deep-sea version of a pill bug on steroids, measuring up to 20 inches long and armored like a prehistoric tank. Found scavenging the ocean floor at 1,600 to 7,500 feet, these bottom-dwellers live in total darkness, using sensitive antennae and chemical cues to find dead whales, fish, and squid that drift down from above. Their hard, segmented exoskeletons and curling defense posture make them look familiar, but unsettlingly oversized, like something you’d expect to see in a sci-fi movie.

What makes giant isopods fascinating is their patience. With so little food on the ocean floor, they’ve adapted to feast when they can and fast for months, sometimes even years. Their metabolism is so slow that some individuals in captivity have refused to eat for over five years and survived. Despite their creepy-crawly looks, they’re non-aggressive, quiet scavengers that play a crucial role in cleaning up the ocean’s dark underworld. If nature ever designed a survivalist doomsday bug, this would be it. Source: BBC Wildlife Magazine

25. Glass Octopus

The glass octopus (Vitreledonella richardi) is one of the deep sea’s most elusive and mesmerizing creatures. Nearly transparent and about the size of a loaf of bread, it lives at depths of 1,000 to 3,000 feet where sunlight disappears. Most of its body, including its head, arms, and mantle, is completely see-through, allowing it to vanish into the dark waters and avoid predators. Only its optic nerves, eyes, and a few internal organs are visible, suspended inside like tiny floating orbs. It’s rarely seen in the wild, making every sighting feel like witnessing a ghost.

What makes the glass octopus surprisingly relatable is its invisibility as a survival mechanism. It doesn’t flash or fight, it simply disappears. Its soft, gelatinous body floats silently through the water, using gentle fin movements to glide with almost no effort. There’s something eerily graceful about its strategy: be so unremarkable, you’re untouchable. In a world that often values boldness, this creature thrives by mastering the art of subtlety and stillness, proof that being quiet and hard to pin down can be a strength. Source: NOAA Ocean Exploration

26. European Cave Salamander

The European cave salamander is a slender, moist-skinned amphibian that lives in the limestone caves and damp rock crevices of Italy and nearby regions. Though some populations emerge at night to feed, many spend their entire lives in near-total darkness deep inside cave systems. With mottled skin ranging from rust to violet-black, this salamander relies on touch, chemical signals, and subtle humidity cues to find insects and spiders in the pitch black. It breathes entirely through its skin and mouth lining, requiring the damp, calm environment that caves provide to survive.

This salamander’s ability to live a quiet, moisture-bound life hidden from chaos makes it relatable. It doesn’t need constant motion or bright lights; it thrives in solitude, taking slow, deliberate steps through its underground labyrinth. Unlike its American cousin, the olm, the European cave salamander retains its eyes and can function in dim light, but it still chooses the shadows. It’s the introvert of the amphibian world, surviving through subtlety, sensitivity, and quiet strength. Source: AmphibiaWeb

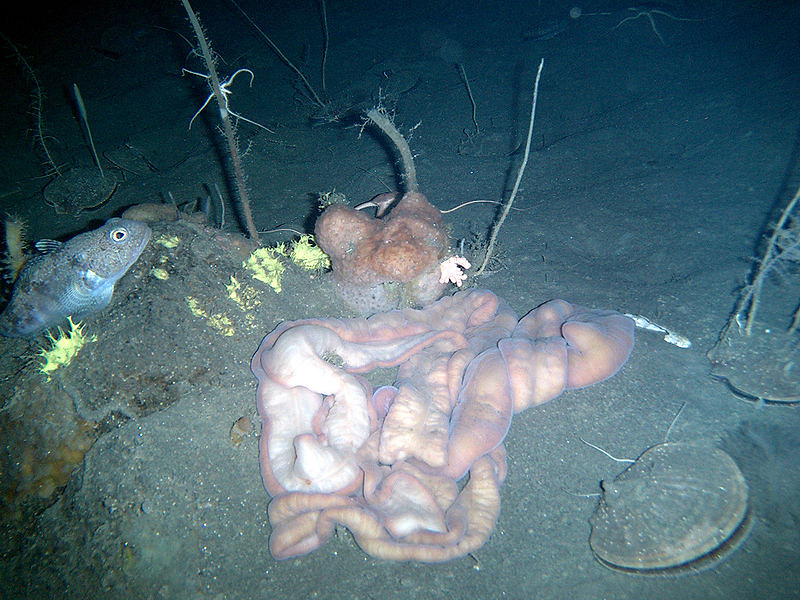

27. Deep-Sea Sea Cucumber

Nicknamed the “headless chicken monster,” Enypniastes eximia is a species of sea cucumber that floats above the ocean floor at depths of 1.6 to 3.7 miles, living in complete darkness. Unlike the squishy blobs you might picture from tide pools, this creature has evolved transparent, wing-like fins and glowing tissues that let it swim gracefully above the seabed. Its body is so translucent you can see its intestines digesting food in real time, an eerie yet oddly mesmerizing trait.

What makes this deep-sea drifter relatable is its quiet efficiency. It floats gently to the seafloor, gulps a mouthful of sediment packed with nutrients, then flutters away before predators notice. No rushing, no panic, just a slow, glowing dance through the abyss. First caught on camera in 2017 by researchers in Antarctica, this bizarre sea cucumber became an internet sensation for its gelatinous charm and utterly unexpected elegance. It’s proof that even in the darkest places, nature can be weird, fantastic, and low-key iconic. Source: BBC Wildlife

28. Frilled Shark

The frilled shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus) is a rare, deep-sea predator that inhabits depths of up to 5,000 feet. Often referred to as a “living fossil,” this eel-like shark has remained relatively unchanged for millions of years. Its name derives from the six pairs of frilly gill slits that give it a distinctive appearance. With a long, slender body and a mouth lined with over 300 trident-shaped teeth arranged in 25 rows, the frilled shark can lunge forward to capture prey, swallowing it whole.

Despite its menacing appearance, the frilled shark leads a slow-paced life in the ocean’s depths, feeding primarily on squid and other deep-sea fish. Its reproductive strategy is equally unique; it has one of the most extended gestation periods of any vertebrate, estimated to be up to three and a half years. The frilled shark’s elusive nature and primitive features offer a glimpse into the ancient past of shark evolution. Source: National Geographic

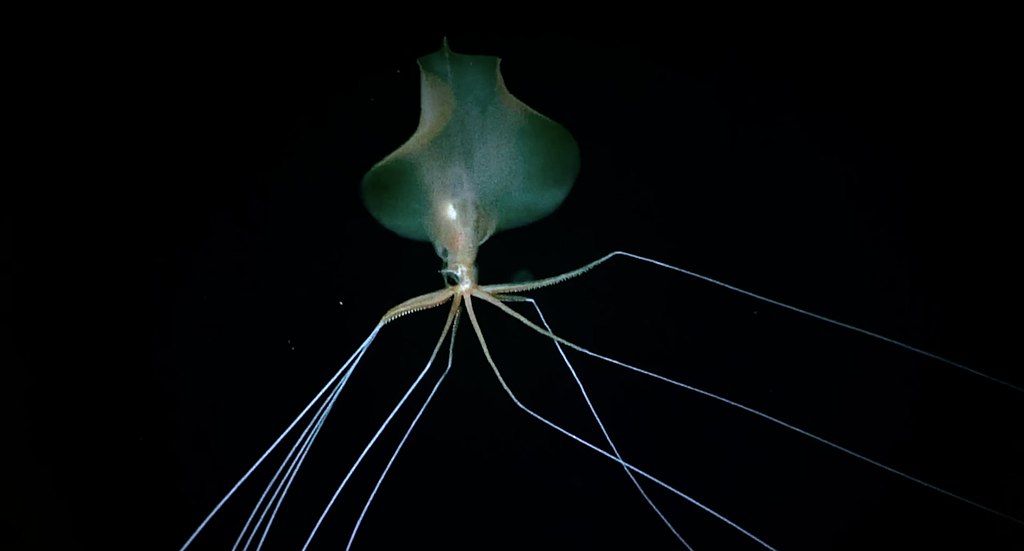

29. Bigfin Squid

The bigfin squid is one of the deep sea’s most mysterious and alien-looking creatures. Rarely seen and rarely captured on camera, this elusive squid has been observed at depths of over 15,000 feet. Its most distinctive features are its extraordinarily long arms and tentacles, which can extend up to 20 feet, held at right angles to its body, giving it a unique “elbowed” appearance. These appendages are believed to be used for capturing prey in the pitch-black depths of the ocean. The Sun

Despite its ghostly appearance, the bigfin squid is not a fearsome predator. Its delicate body and slow movements suggest a passive hunting strategy, likely drifting through the water column and using its long limbs to ensnare small organisms. The scarcity of sightings and specimens means that much about this creature remains unknown, adding to its enigmatic allure. Source: MBARI

30. Trogloraptor Spider

Discovered in 2010 within the caves of southwestern Oregon, the Trogloraptor spider is a remarkable arachnid that led scientists to establish a new family, Trogloraptoridae, due to its distinctive features. Measuring up to 3 inches (7.6 cm) across with legs extended, this spider exhibits a yellow-brown coloration and possesses unique, hook-like claws at the ends of its legs. These claws are believed to aid in capturing prey, although the exact hunting behavior remains a subject of study.

The Trogloraptor constructs simple webs consisting of a few strands, typically suspended from cave ceilings. Despite its fearsome appearance, it is not considered dangerous to humans. The discovery of this spider underscores the rich biodiversity that can exist in subterranean environments and highlights the potential for finding previously unknown species in such habitats. (SciTech Daily)

31. Whiplash Squid

The Whiplash Squid, belonging to the family Mastigoteuthidae, is a deep-sea cephalopod known for its elongated, whip-like tentacles and bioluminescent capabilities. These squids inhabit the mesopelagic to bathypelagic zones of oceans worldwide, typically found at depths ranging from 1,600 to 6,500 feet. Their large, ovate fins, which can constitute up to 80% of their mantle length, aid in hovering above the seafloor. The tentacles are equipped with minute, sticky suckers, allowing them to capture prey efficiently. Whiplash squids exhibit a unique hunting posture known as the “tuning fork” position, where they hover vertically in the water column with tentacles extended downward, ready to ensnare unsuspecting prey.

Bioluminescence plays a crucial role in their survival, with photophores located on various parts of their bodies, including the skin and around the eyes. These light-producing organs aid in communication, camouflage, and attracting prey in the pitch-black environment of the deep sea. Despite their intriguing adaptations, much about the Whiplash Squid remains a mystery due to the challenges of studying deep-sea organisms. Continued exploration and research are essential to uncover the secrets of these enigmatic creatures and understand their role in the ocean’s ecosystem. Source: Wikipedia

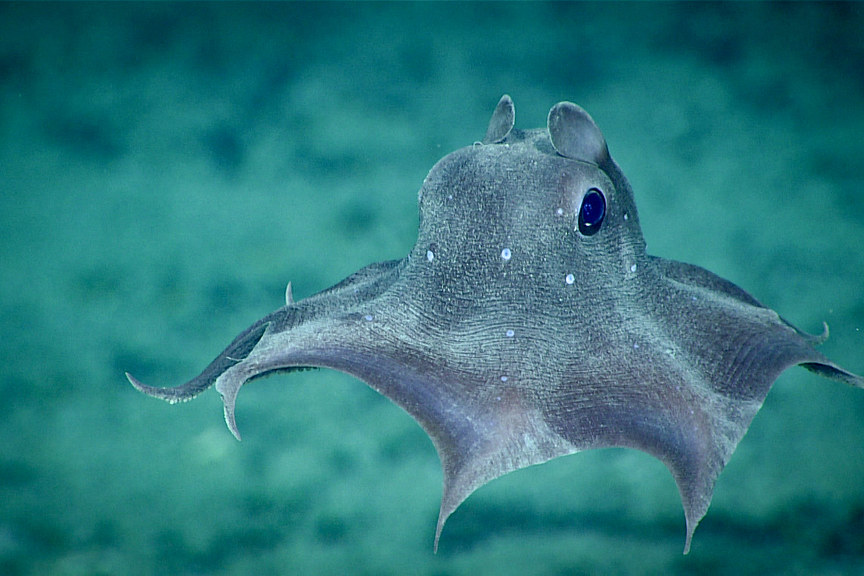

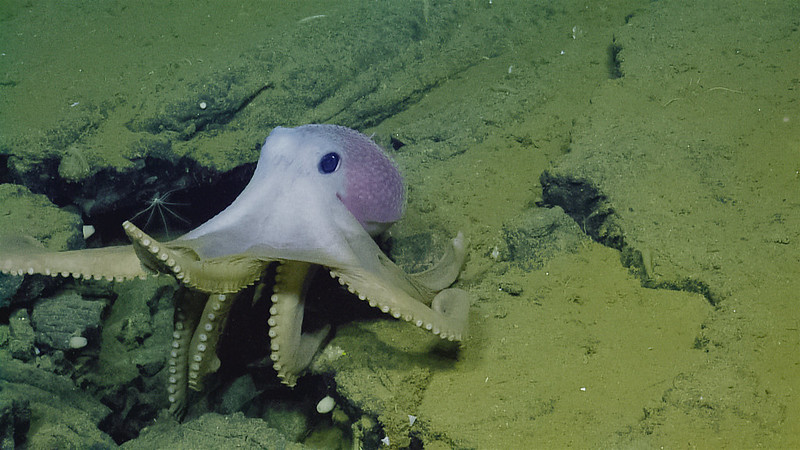

32. Dumbo Octopus

The Dumbo octopus, named for its ear-like fins resembling the Disney character Dumbo’s ears, is a deep-sea cephalopod found at extreme depths ranging from 9,800 to 13,000 feet (3,000 to 4,000 meters) below the ocean surface. Unlike many other octopus species, Dumbo octopuses do not possess an ink sac, as the pitch-black depths they inhabit render such a defense mechanism unnecessary. Their gelatinous bodies and unique fin structures allow them to hover and propel gracefully through the water, making them well-adapted to the high-pressure, low-temperature environments of the deep sea.

These elusive creatures are benthic, meaning they live on or near the ocean floor, and are known to feed on worms, crustaceans, and other small invertebrates. Due to the inaccessibility of their habitat, Dumbo octopuses are rarely observed, and much about their behavior and biology remains a mystery. However, their distinctive appearance and adaptations make them a subject of interest for deep-sea researchers and enthusiasts alike. Source: Oceana Org

33. Giant Amphipod

The giant amphipod is a supersized cousin of the common sand flea, but instead of scuttling under a beach umbrella, it haunts the hadal depths of the ocean, often found more than 20,000 feet below the surface. First discovered in the 1980s in the Kermadec Trench, this deep-sea crustacean can grow over 13 inches long, a monstrous size compared to typical amphipods, which barely reach a centimeter. With its semi-transparent exoskeleton and alien-like body, it resembles a creature built for sci-fi rather than seafloor scavenging.

What’s especially eerie about the giant amphipod is its sheer resilience. It thrives in water temperatures just above freezing and pressures over 1,000 times greater than those at sea level. Its diet consists of anything that sinks, dead fish, whale carcasses, and organic debris. Scientists believe its gigantism may be an adaptation to limited food supply and cold temperatures, allowing it to store energy and move efficiently in a near-starved ecosystem. It’s a deep-sea hoarder, quietly cleaning up the ocean’s floor in total darkness. Source: NOAA Ocean Exploration

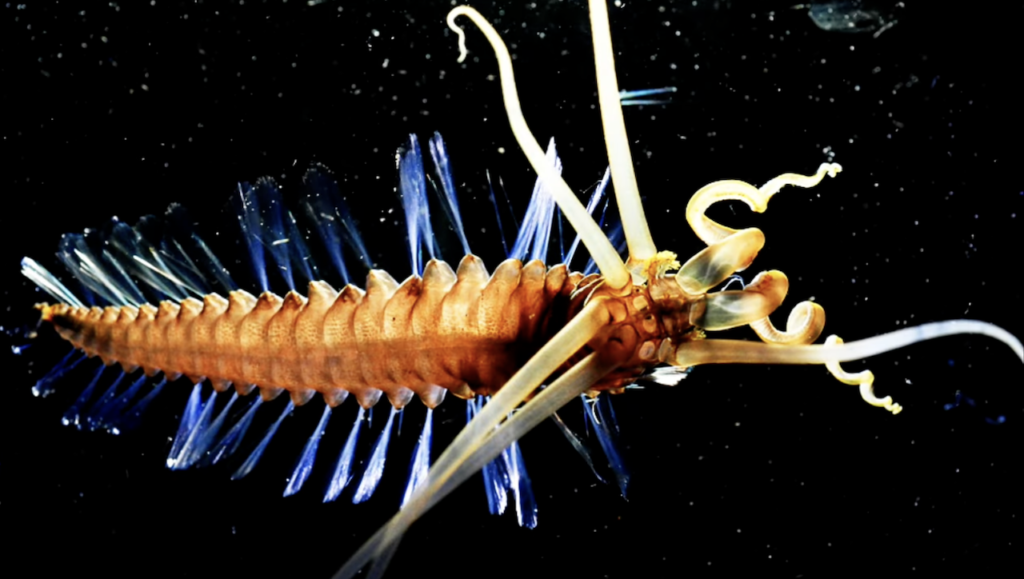

34. Squidworm

Discovered in 2007 in the deep waters of the Celebes Sea, the squid worm is a remarkable species of polychaete annelid that thrives at depths between 6,700 and 9,500 feet (2,000–2,900 meters). Measuring approximately 4 inches (10 centimeters) in length, this free-swimming worm possesses ten elongated, tentacle-like appendages on its head, which it uses to collect marine snow and organic particles drifting down from the ocean’s upper layers. Its body is equipped with 25 pairs of paddle-like parapodia that facilitate graceful movement through the water column.

The squidworm’s unique morphology includes specialized sensory organs called nuchal organs, which detect chemical environmental cues, aiding navigation and feeding. Its semi-transparent body allows for observing internal structures, providing valuable insights into its anatomy and physiology. The discovery of Teuthidodrilus samae highlights the vast biodiversity of deep-sea ecosystems and underscores the importance of continued exploration in uncovering the mysteries of the ocean’s depths. Source: National Geographic

35. Bloody-belly Comb Jelly

The bloody-belly comb jelly is a deep-sea ctenophore known for its striking red coloration, which appears nearly black in the lightless depths of its habitat, providing effective camouflage. First described in 2001, this species inhabits the mesopelagic zone at depths ranging from 820 to 3,280 feet (250–1,000 meters) off the coast of California. Unlike true jellyfish, comb jellies like Lampocteis cruentiventer use rows of cilia, known as comb rows, to propel themselves through the water, creating a shimmering effect as light diffracts off their moving cilia. Source: IFLScience

The bloody-belly comb jelly’s red pigmentation serves a crucial function: it masks the bioluminescence of its prey, preventing the glow from revealing its presence to potential predators. This adaptation is particularly advantageous in the deep sea, where red wavelengths are absorbed quickly, rendering red-colored organisms nearly invisible. The species’ unique morphology and survival strategies offer valuable insights into the adaptations required for life in extreme oceanic environments.

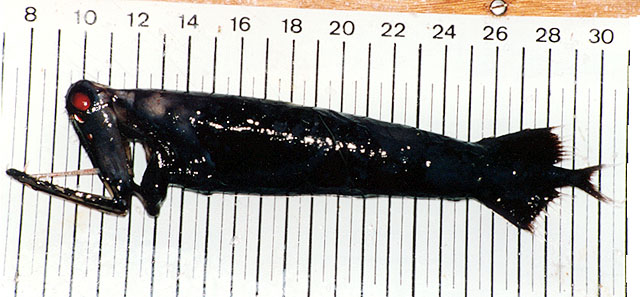

36. Fangtooth Fish

The fangtooth fish may only grow to about 6 inches long, but it boasts the most significant teeth-to-head ratio of any known fish and lives in some of the deepest, darkest parts of the ocean. Found at depths between 650 and 16,400 feet, it has massive, needle-like teeth so long they require special sockets in the upper jaw to avoid puncturing the brain. With sunken eyes, rough armor-like skin, and a perpetual scowl, the fangtooth cuts a nightmarish figure in the abyss. But in reality, it’s shy, slow, and mainly feeds on small fish and crustaceans.

Despite its fearsome look, the fangtooth is a gentle drifter, using pressure-sensitive receptors to detect prey in the darkness. It’s capable of vertical migration, rising closer to the surface at night to feed, then descending daily into the black. Juveniles look nothing like adults; they are slender, pale, and without their signature teeth, which offer clues to deep-sea developmental biology. The fangtooth’s adaptations to pressure, cold, and perpetual night make it one of the best-known ambassadors of the twilight and midnight zones. Source: MBARI

37. Dragonfish

Dragonfish are deep-sea predators found at depths of up to 5,000 feet (1,500 meters). They possess large heads, sharp teeth, and bioluminescent photophores along their bodies. Some species can produce red light, invisible to most other deep-sea creatures, allowing them to illuminate prey without revealing their presence.

Their ability to emit and perceive red light is due to specialized pigments in their eyes and light-producing organs. This adaptation provides a significant hunting advantage in the dark ocean depths. Dragonfish feed on smaller fish and invertebrates, using their light to lure and detect prey in the pitch-black environment. Source: National Geographic

38. Eyeless Huntsman Spider (Sinopoda scurion)

Discovered in a cave in Laos in 2012, Sinopoda scurion is the first known species of huntsman spider to be completely eyeless. Adapted to life in total darkness, this spider has lost its pigmentation and visual organs, relying instead on other senses to navigate and hunt within its subterranean habitat. Measuring about 0.8 inches (2 centimeters) in body length, it preys on small invertebrates, using its heightened tactile and chemical senses to detect vibrations and chemical environmental cues.

The discovery of Sinopoda scurion provides valuable insights into the evolutionary processes in isolated, lightless environments. Such adaptations highlight the remarkable plasticity of life and its ability to thrive under extreme conditions, offering a glimpse into the biodiversity beneath the Earth’s surface. Source: WIRED

39. Proboscis Worm

The proboscis worm, Parborlasia corrugatus, is a remarkable ribbon worm inhabiting the cold, oxygen-rich waters of the Southern Ocean. Measuring up to 6.5 feet (2 meters) in length, this unsegmented worm is both predator and scavenger, feeding on a diverse diet that includes detritus, diatoms, gastropods, amphipods, isopods, sponges, jellyfish, sea stars, mollusks, anemones, and polychaete worms. Its distinctive feature is a barbed, extendable proboscis housed within a fluid-filled cavity called the rhynchocoel. This organ can be rapidly everted to capture prey, aided by adhesive secretions that secure its meal. Wikipedia

Adapted to life in the deep sea, P. corrugatus lacks a dedicated respiratory system, instead absorbing oxygen directly through its skin. In low-oxygen conditions, it flattens and elongates its body to increase surface area, facilitating more efficient gas exchange. Additionally, it secretes an acidic mucus with a pH of 3.5 as a chemical defense against potential predators. This species is widely distributed across the Southern Ocean, from the intertidal zone to depths of nearly 11,800 feet (3,590 meters), and plays a vital role in the benthic ecosystem as both a consumer and a nutrient recycler.

40. Movile Cave Ecosystem (Romania)

Movile Cave, located in southeastern Romania, harbors one of Earth’s most extraordinary subterranean ecosystems. Sealed from the surface for approximately 5.5 million years, this cave supports a complex web of life independent of sunlight. Instead, its ecosystem is based on chemosynthesis, where bacteria derive energy from oxidizing hydrogen sulfide and methane, forming the foundation of the food web. These microbial mats are grazed upon by various invertebrates, which are preyed upon by higher-level consumers.

The cave is home to 57 known animal species, 37 of which are endemic. Notable inhabitants include the blind water scorpion (Nepa anophthalma), the centipede (Cryptops speleorex), and the snail (Heleobia dobrogica). These organisms have adapted to the cave’s toxic atmosphere, characterized by high concentrations of carbon dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, and low oxygen levels. Adaptations include loss of pigmentation and eyesight, enhanced sensory organs, and specialized respiratory systems. The unique conditions of Movile Cave provide valuable insights into life in extreme environments and have implications for the study of potential extraterrestrial life. Source: UNESCO

41. Osedax Worm (Osedax mucofloris)

Nicknamed the “zombie worm,” Osedax mucofloris lives on the skeletons of dead whales that have fallen to the seafloor. Found at depths between 1,000 and 11,000 feet, these bone-eating worms have no eyes, stomach, or mouth. Instead, the females secrete acid to bore into bones and use root-like structures to absorb collagen and lipids. They rely on symbiotic bacteria to digest these nutrients, a hauntingly elegant solution for surviving in complete darkness with no direct food source.

Even stranger, male zombie worms don’t roam the seafloor at all. They’re microscopic and live by the hundreds inside the gelatinous tubes of a single female, never developing beyond the larval stage. These worms thrive in total darkness, and their eerie biology has rewritten what we thought life could do without sunlight. By turning death into a long-term feast, Osedax worms anchor a rich micro-ecosystem, proving that even decay becomes a source of life in the darkest places. Source: MBARI

42. Stoplight Loosejaw

The stoplight loosejaw is a deep-sea dragonfish with one of the most unique visual systems in the ocean. It inhabits depths of 1,600 to 3,300 feet, where light barely exists, and has evolved the ability to emit both red and blue bioluminescent light. Most deep-sea creatures can’t perceive red wavelengths, so the stoplight loosejaw uses its red bioluminescence like night vision, silently scanning for prey that has no idea it’s being watched. Its jaw is thin, hinged like a trap, and can open nearly 120 degrees, allowing it to snatch up crustaceans and small fish with lightning speed.

What sets this predator apart isn’t just its stealth and surreal anatomy. Its lower jaw is detached from its head, connected only by ligaments and muscle, eliminating water resistance during strikes. Meanwhile, its eyes contain unique pigments that allow it to see the red light it produces, an extreme adaptation scientists are still studying. In a world where every movement costs energy, this fish has weaponized invisibility, speed, and silent strategy to dominate the twilight zone. Source: Natural History Museum

43. Aitken Cave Springtail

Deep beneath the Colorado Plateau, in the limestone chambers of Aitken Cave, lives a ghostly white springtail barely visible to the naked eye. Pygmarrhopalites osborni is a cave-adapted arthropod, less than 2 millimeters long, that has evolved without eyes, pigmentation, or wings. It’s part of a group of hexapods known for their unique “springing” tail-like structure, which can launch them through the air. But down here, where the ceilings drip with mineral-laced moisture and no light has entered for thousands of years, they move slowly and cling to cave walls coated in microbial film.

What makes this springtail extraordinary isn’t just its appearance and ecological role. It feeds on decomposing fungi, bacteria, and biofilms, recycling organic matter in an ecosystem without sunlight or surface nutrients. It’s been called a keystone species in its tiny but essential microhabitat. The discovery of P. osborni in 2010 reminded scientists how little we know about life in cave ecosystems, especially in isolated karst systems where entire lineages of animals evolve in total darkness, unseen and unstudied. Source: National Speleological Society

44. Deep-Sea Lizardfish (Bathysaurus ferox)

The deep-sea lizardfish is a top predator in one of the most extreme habitats on Earth, the abyssal plains. Found at depths between 3,300 and 8,200 feet, it’s one of the deepest-living bony fish ever documented. With its long, torpedo-shaped body, glassy eyes, and a mouth full of sharp, fang-like teeth, it lurks motionless on the seafloor, waiting to ambush prey. Its translucent skin gives it an eerie ghost-like presence, while its powerful jaws and expandable stomach allow it to swallow prey nearly as large as itself.

Despite its menacing appearance, Bathysaurus ferox leads a solitary, slow-paced life. It’s a sit-and-wait predator, conserving energy in a habitat where food is scarce and meals might come days or weeks apart. It also possesses both male and female reproductive organs, allowing it to mate with any other member of its species, a helpful trait in the sparsely populated deep. With its ancient features and perfectly tuned survival strategy, this lizardfish rules a world that sees no sun, no mercy, and no end to the strange. Source: Smithsonian Ocean

45. Mariana Snailfish (Pseudoliparis swirei)

The Mariana snailfish is the deepest-living fish ever recorded, thriving at depths over 26,000 feet in the Mariana Trench. It looks soft, ghostlike, pale, nearly translucent, and without scales, yet astonishingly resilient. At pressures over 1,000 times that at sea level, most fish bodies would collapse. However, the Mariana snailfish has a flexible skeleton, fluid-filled tissues, and specialized proteins that keep its cells from imploding. It feeds on tiny amphipods and crustaceans, floating just above the trench floor in one of the most hostile places on Earth.

Despite living in an environment colder than freezing and darker than space, Pseudoliparis swirei moves with surprising ease. Scientists have captured rare footage of it gliding gracefully near baited cameras, calmly feeding while other life forms struggle to exist. Its adaptations have challenged our understanding of how vertebrates function under extreme pressure. Rather than armored or monstrous, the snailfish is almost delicate—an eerie reminder that some of the planet’s most extreme survivors wear the gentlest disguises. Source: Live Science

46. Alabama Cave Shrimp (Palaemonias alabamae)

The Alabama cave shrimp is a critically endangered crustacean found only in a few isolated limestone caves in northern Alabama. This translucent, eyeless shrimp measures just over an inch long and glides silently through groundwater-filled caverns where light has never touched. With no need for vision or pigment, it relies on finely tuned antennae to navigate and locate decaying organic matter, fungi, and bacteria. It’s one of the rarest cave species in North America and indicates groundwater health.

Its life is entirely tied to the purity of its underground habitat—pollution from surface runoff or human development can quickly jeopardize its fragile ecosystem. This shrimp’s reproductive rate is extremely slow, and juveniles take years to mature, making recovery difficult once populations decline. Conservation efforts are underway to monitor water quality and preserve the karst systems where they survive. Delicate, ghostlike, and perfectly adapted to the dark, the Alabama cave shrimp is a silent sentinel of Earth’s unseen underground world. Source: U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service

47. Hydrothermal Vent Octopus (Muusoctopus robustus)

Living thousands of feet below the ocean surface near hydrothermal vents, the hydrothermal vent octopus (Muusoctopus robustus) thrives in one of the most volatile environments on Earth. Found in the Pacific at depths of 7,000 to 10,000 feet, this deep-sea octopus doesn’t rely on sunlight but instead lives off the heat and nutrients released by undersea volcanic activity. It has a ghostly white body, no ink sac, and a surprisingly calm demeanor, even as superheated, mineral-rich water gushes nearby.

What truly stunned scientists was its parenting behavior. In 2014, researchers discovered a female vent octopus guarding her eggs on a rocky ledge for nearly four and a half years, the longest known brooding period in any animal. Without eating, she clung to life while protecting her developing young in the pitch dark, against scalding currents and frigid pressure. Her patient, quiet vigil redefined what we thought possible in the animal kingdom and revealed a rare portrait of devotion in the deep sea. Source: MBARI

48. Blind Cave Loach

The blind cave loach is a rare fish discovered in the subterranean rivers of Thailand, particularly in flooded limestone caves with no access to light. This loach is about 2.5 inches long and has evolved without eyes or pigment, giving it a pinkish, semi-transparent appearance. Its long barbels, whisker-like sensory organs, help it feel its way through narrow crevices and rocky tunnels, sensing vibrations and chemical traces in the water instead of relying on vision.

Unlike other cavefish, the blind cave loach is a strong swimmer, capable of navigating fast-moving underground streams and climbing vertical cave walls using its muscular body and sucker-like fins. It feeds on tiny invertebrates and biofilms that grow on submerged rock. Because of its agility and narrow habitat range, it has remained elusive to researchers, and its conservation status remains poorly understood. Still, it’s a testament to how evolution bends biology to suit even Earth’s strangest, most silent environments. Source: TED Talk

49. Scaly-Foot Snail

The scaly-foot snail is one of the most metal creatures on Earth. Found only at hydrothermal vents in the Indian Ocean, this deep-sea snail lives over 8,000 feet below the surface and has evolved iron-infused scales and a shell partially reinforced with pyrite and greigite (a magnetic mineral). Its armored body can withstand extreme pressure and the acidic, superheated conditions near black smoker vents. It feeds on energy not from the sun, but from bacteria that convert sulfur chemicals in the vent water into nutrients, a process called chemosynthesis.

This snail is not only a marvel of evolution but a living paradox. Its outer shell has three layers: a hard iron sulfide outer shield, a squishy middle layer that absorbs shock, and a crystalline inner lining. That makes it one of the best natural impact-resistant structures known to science. It doesn’t just survive the deep, it thrives in one of the harshest environments imaginable, fusing biology and geology into a slow-moving tank with a heart. Source: Nature

50. Deep-Sea Hatchetfish

The deep-sea hatchetfish looks like something dreamed up in a shadowy lab, its silver, wafer-thin body gleams like metal, shaped almost like a hatchet blade with bioluminescent organs lining its belly. Found between 600 and 4,500 feet deep, this fish uses its light-producing organs to perform counter-illumination: it matches the faint light above to make itself invisible from below, effectively erasing its silhouette. It’s a perfect trick for a fish that wants to eat without being eaten in the midwater twilight zone.

Measuring just 4 to 6 inches long, the hatchetfish is a quiet hunter that preys on small crustaceans and plankton using its upward-facing tubular eyes, which are adapted to detect the slightest shimmer of movement in the dark. Scientists believe its eyes can rotate independently, giving it almost panoramic vision in the gloom. Though it looks fragile, it’s finely tuned for stealth survival in a lightless world where seeing, but not being seen, means everything. Source: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute

51. Blind Cave Eel

The blind cave eel (Ophisternon candidum) is a pale, serpent-like fish that slithers through Australia’s darkest underground waters with no eyes, pigment, or need for light. Growing up to 16 inches long, it’s the largest known cavefish in the country, yet it’s rarely seen. Instead of vision, this eerie eel relies on vibration and chemical cues to find small invertebrates in submerged limestone tunnels, often in complete silence. Its ghostly, pink-white body blends perfectly into the mineral-rich aquifers it inhabits, mostly around the Cape Range and Barrow Island in Western Australia. With no fins or scales and an elongated, slimy frame, it moves more like a snake than a typical fish, weaving effortlessly through narrow crevices.

The blind cave eel is considered critically endangered, partly because it’s so uniquely tied to one of the most fragile groundwater systems in the world. It’s thought to have descended from a once-surface-dwelling ancestor that became trapped underground millions of years ago, slowly adapting to the dark through loss of eyesight and pigmentation. Scientists are still trying to fully understand its reproduction and population size, as it’s so elusive that only a few specimens have ever been observed in the wild. Its survival depends on pristine, undisturbed water, meaning any contamination from mining, tourism, or development could spell disaster. It’s not just a marvel of evolution, it’s a canary in the coal mine for subterranean ecosystems. Source: Fishes of Australia

52. Madison Cave Isopod

The Madison Cave isopod is one of the rarest subterranean crustaceans in the United States. Native only to parts of Virginia and West Virginia, this eyeless, unpigmented isopod lives in water-filled limestone caves buried deep within the Appalachian karst. Females can grow up to 18 millimeters long, making them one of the larger isopods adapted to freshwater cave life. With a flat, segmented body and paddle-like limbs, it glides slowly through aquifers and cave streams, navigating entirely by touch and chemical cues in total darkness.

First discovered in 1958, the Madison Cave isopod has become a key indicator of groundwater health in its fragile ecosystem. Because it depends on clean, oxygen-rich water deep underground, it is susceptible to pollution and development. Its entire known population is restricted to just a few cave systems, and it’s been listed as Threatened under the U.S. Endangered Species Act since 1982. Studied for its unique genetics and ecological role, this ghostly isopod is a flagship species for underground biodiversity. Source: USDA

53. Lee County Cave Isopod

Endemic to a single cave system in Lee County, Virginia, the Lee County cave isopod is a tiny, translucent creature that exists nowhere else on Earth. Just 7 millimeters long, it lacks eyes and pigment entirely, relying on its flattened body and highly sensitive antennae to navigate the gravel-bottomed cave streams where it lives. It hides beneath submerged rocks, feeding on organic debris and biofilm that drifts through the aquifer’s slow-moving currents. With no light, seasonal cues, or surface access, its entire life plays out in silence beneath the Appalachian foothills.

The Lee County cave isopod is one of North America’s most imperiled subterranean species. Listed as Endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and classified as “Endangered” by the IUCN, it faces severe threats from groundwater pollution, surface development, and reduced aquifer recharge. Conservationists consider it a vital sentinel species, and if something goes wrong in the water supply, this isopod is one of the first to show signs of stress. Its ghostlike form may be small, but its survival speaks volumes about the health of our hidden freshwater systems. Source: Virginia DCR

54. Florida Cave Isopod

The Florida cave isopod is a tiny, translucent crustacean that dwells in the hidden freshwater caves of the Sunshine State. Measuring up to 15 millimeters long, it has no eyes, no pigment, and a flattened body designed for slipping through narrow aquatic passageways. Like other troglobitic isopods, it lives under rocks or drifts through groundwater-fed systems, feeding on biofilm, decaying organic matter, and microscopic life that filters through the limestone. Rare and largely unseen, it represents a quiet thread in Florida’s vast and little-known subterranean web.

This elusive species is considered critically imperiled at the state level, despite lacking federal protection. Its vulnerability stems from its tiny range and dependence on uncontaminated, oxygen-rich aquifers, habitats increasingly threatened by agricultural runoff, development, and water table shifts. Because it’s so rarely encountered, the Florida cave isopod is still a mystery to science, but its presence signals ancient lineage and environmental fragility. Source: Florida Natural Areas Inventory

The Dark Still Has Secrets to Tell

We like to think of life as something that depends on sunshine, seasons, and surface rules, but these creatures prove otherwise. Life finds a way in the crushing pressure of the deep sea, in caves sealed for millions of years, or in radioactive rock miles beneath our feet, a weird, glowing, clawed, eyeless way. And it’s not just surviving; it’s thriving, adapting, and rewriting the rules of biology.

What these organisms teach us isn’t just about science, it’s about resilience, innovation, and the eerie beauty of nature unlit. They remind us that there’s still so much we don’t understand about our planet, maybe just the world beyond it. Because if life can thrive here, in the cold and the dark, imagine what might be waiting out there.