1. Laophis crotaloides

Laophis crotaloides is a mysterious extinct snake from the Pliocene Epoch, estimated to have lived between 2 and 5 million years ago. While its exact size remains uncertain, fossil evidence suggests it was larger than most modern venomous snakes. This ancient serpent is believed to have inhabited southeastern Europe, thriving in diverse habitats that supported large mammals. Its massive vertebrae hint at a snake capable of taking down substantial prey, possibly including early humans. Laophis likely relied on both its size and venom to subdue its victims, making it a formidable predator.

The limited fossil record has left many questions unanswered about its behavior and ecology, but its discovery has sparked significant interest among paleontologists. It serves as a reminder of the incredible biodiversity that once existed in prehistoric Europe, a region now dominated by smaller reptiles and mammals. The extinction of Laophis may have been influenced by climatic shifts or competition with other predators. Its name, which references its rattlesnake-like features, suggests it may have had characteristics similar to modern pit vipers. Laophis crotaloides continues to be an enigmatic figure in paleontology, representing a lost world of giant serpents and the ecosystems they once dominated.

2. Titanoboa cerrejonensis

Titanoboa cerrejonensis is perhaps the most famous extinct snake, reigning as the undisputed king of its era during the Paleocene Epoch around 60 million years ago. This colossal serpent measured over 42 feet (13 meters) in length and weighed more than a ton, making it the largest snake ever discovered. Titanoboa inhabited the tropical rainforests of what is now Colombia, thriving in warm, swampy environments. According to Smithsonian Magazine, its diet consisted primarily of large fish, though it may have also preyed on other reptiles and aquatic creatures. Paleontologists believe its massive size was made possible by the high temperatures of its environment, which allowed cold-blooded creatures like Titanoboa to grow to enormous proportions.

Fossilized remains of Titanoboa have been found in the Cerrejón coal mines, providing a glimpse into a prehistoric world dominated by gigantic reptiles. Its discovery has offered valuable insights into the climate and ecosystems of the Paleocene, a period of recovery following the mass extinction that wiped out the dinosaurs. The snake’s immense girth and length made it a top predator, capable of overpowering almost any animal in its territory. Titanoboa’s existence underscores the sheer scale of biodiversity in ancient rainforests and how climate shaped the evolution of such extraordinary species. Its discovery has become a symbol of paleontological achievement, inspiring both awe and a better understanding of prehistoric life.

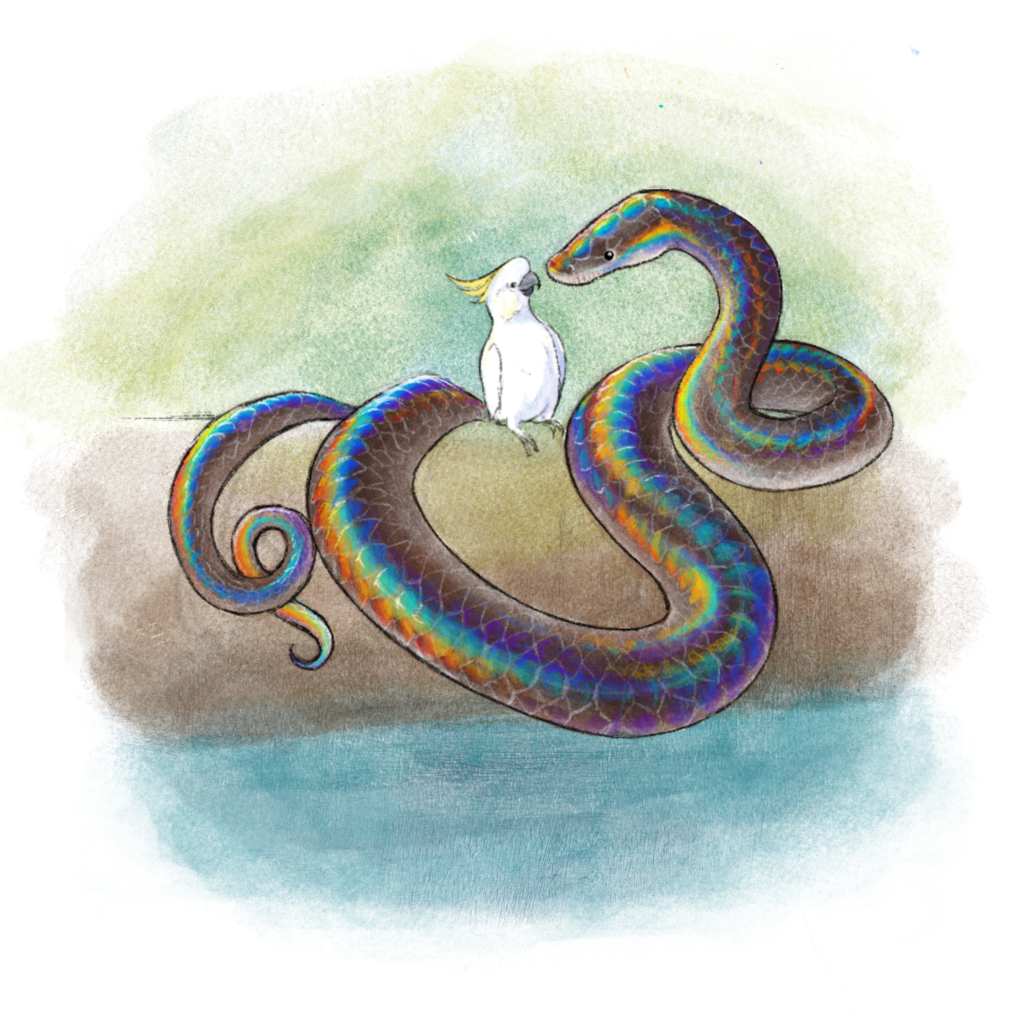

3. Wonambi naracoortensis

Wonambi naracoortensis was a giant, non-venomous snake that thrived during the Pleistocene Epoch around 50,000 years ago. Reaching an estimated length of 20 feet (6 meters), it was a formidable predator in ancient Australia, as discussed in a study published in The Royal Society. Unlike modern venomous snakes, Wonambi lacked fangs and instead relied on its immense muscular strength to constrict its prey. This powerful ambush predator targeted large marsupials, using its camouflage to blend seamlessly into its surroundings. It likely inhabited wetlands and other areas with dense vegetation, where it could wait for unsuspecting prey to wander by.

Scientists believe its extinction was caused by a combination of factors, including significant climate changes and the arrival of humans in Australia. As humans introduced new hunting methods and altered the landscape, many large animals that formed Wonambi’s diet also began to disappear. Fossils of Wonambi have been discovered in caves and ancient deposits, providing insight into its behavior and environment. It is considered part of the extinct snake family known as Madtsoiidae. The existence of such a massive constrictor highlights the unique and diverse ecosystems that once flourished in prehistoric Australia.

4. Sanajeh indicus

Sanajeh indicus was a medium-sized snake from the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 70 million years ago, that proved size isn’t everything when it comes to being deadly. Measuring around 10 feet (3 meters) in length, it was smaller than some of its contemporaries but no less dangerous. Fossil evidence suggests that Sanajeh targeted dinosaur hatchlings, making it a specialized predator of the era. One particularly striking fossil shows a Sanajeh coiled around a dinosaur nest, offering direct evidence of its predatory behavior. This snake likely relied on its agility and ambush tactics to capture young dinosaurs before they could escape. According to National Geographic, its habitat in ancient India was marked by diverse ecosystems, including forests and floodplains where dinosaurs and other reptiles thrived.

The presence of Sanajeh highlights the complex food chains of the Cretaceous, where even small predators played crucial roles. Its discovery has provided unique insights into predator-prey interactions during the age of dinosaurs. Paleontologists believe its name, which means “old gape” in Sanskrit, reflects its ability to swallow relatively large prey despite its modest size. Sanajeh’s behavior and ecological role illustrate the adaptability and cunning of prehistoric snakes, showcasing their evolutionary success long before modern snakes evolved.

5. Palaeophis toliapicus

Palaeophis toliapicus was an impressive marine snake that lived during the Early Eocene Epoch, around 55 million years ago. With an estimated length of up to 30 feet (9 meters), it was among the largest snakes of its time. Unlike terrestrial snakes and as discussed by ScienceDirect, Palaeophis adapted to life in the water, thriving in coastal environments and shallow seas. Fossil evidence indicates it hunted fish and other marine creatures, using its streamlined body and powerful swimming abilities to pursue prey. Its fossils have been found in Europe, suggesting it lived along ancient coastlines that were vastly different from today. Palaeophis represents an intriguing branch of snake evolution, where some species ventured into aquatic habitats and thrived there.

Its size and predatory skills would have made it a dominant force in its ecosystem, competing with other marine predators for resources. The study of Palaeophis has helped scientists understand how snakes adapted to different environments over millions of years. It also highlights the diversity of marine life during the Eocene, a period when many modern groups of animals began to emerge. Despite its extinction, Palaeophis remains a fascinating example of evolutionary experimentation in reptiles. Its legacy lives on in the study of marine snakes and their ancient relatives.