The Cost Of Betting On The Wrong Future

There was a fleeting moment at the turn of the millennium when we genuinely believed the pavements of our cities were about to change forever. When Dean Kamen unveiled the Segway PT in 2001, the hype was nothing short of messianic, with tech titans predicting it would be more significant than the personal computer. It promised a revolution in urban mobility that would render cars obsolete for short journeys while making the humble act of walking seem dreadfully antiquated. We were sold a vision of a whisper-quiet, self-balancing future where every commuter would glide effortlessly to the office, yet the reality proved to be far more awkward and expensive than the glossy brochures suggested.

The downfall of the Segway serves as a fascinating case study in what happens when brilliant engineering meets a world that simply is not ready for it. Instead of becoming a ubiquitous necessity, the machine found itself relegated to the fringes of society, becoming a punchline in sitcoms or a niche tool for security guards and tourists. It is a story about the disconnect between Silicon Valley ambition and the practical constraints of urban infrastructure and social etiquette. Understanding why the Segway failed to conquer the world helps us look more critically at today’s tech promises, reminding us that even the most innovative inventions can crumble if they do not solve a problem that people actually have.

The Visionary Hype Phase

The initial excitement surrounding the Segway was fueled by a carefully orchestrated mystery campaign that suggested the invention would fundamentally alter the layout of modern cities. Code-named “Ginger,” the project attracted investment from heavyweights like Jeff Bezos and John Doerr because they believed it represented a paradigm shift in thermodynamics and personal freedom. Steve Jobs famously remarked that the design was as significant as the PC, although he later critiqued the aesthetics for looking less than cool. This period was defined by an almost blind faith in the hardware because the public was told that the device would make car-centric urban planning a thing of the past and reduce carbon emissions overnight.

However, the reality of the launch in December 2001 struggled to live up to the astronomical expectations set by the media and the investors involved. While the self-balancing gyroscopic technology was a genuine marvel of engineering, the price tag of five thousand dollars made it a luxury toy rather than a populist tool for the masses. People quickly realised that while the machine worked perfectly on a technical level, it did not fit into the existing social or legal frameworks of most countries. The hype created a pedestal so high that anything less than a total global revolution felt like a disappointment, and the Segway was soon battling a perception problem that it never truly managed to escape.

Prohibitive Entry Costs

One of the primary reasons the Segway failed to gain traction among everyday commuters was the staggering initial purchase price which hovered around the five thousand dollar mark. For the average person in the early 2000s, this was the price of a decent used car or a significant down payment on many other life essentials. The company had marketed the device as a replacement for walking and short drives, yet the financial barrier meant only the incredibly wealthy or the most dedicated tech enthusiasts could actually afford to participate. This pricing strategy immediately alienated the very demographic that needed a “last mile” transport solution and instead pigeonholed the Segway as an elitist gadget for the wealthy elite.

Furthermore, the high cost was not just a barrier for individual buyers but also for the retailers who were expected to stock and service these complex machines. Maintenance was expensive because the components were bespoke and required specialised knowledge to repair, which meant that the long-term cost of ownership remained high. Unlike a bicycle which can be fixed at a local shop for a few pounds, a Segway required a dedicated infrastructure that simply did not exist at the time of its release. This financial friction ensured that the device stayed out of reach for the general public, and as the years passed, the price failed to drop significantly enough to trigger the mass adoption that the inventors had originally envisioned.

Regulatory Roadblocks Appear

The Segway arrived in a world that had no idea where to put it because it was too fast for the pavement and too slow for the road. Governments across the globe struggled to categorise the device, with many cities eventually banning it from public footpaths due to concerns over pedestrian safety and the sheer bulk of the machine. In the United Kingdom, the Department for Transport famously ruled that the Segway was a motor vehicle and therefore could not be used on pavements, but it also lacked the necessary safety features like indicators to be legal on the road. This left owners in a legal limbo where their expensive new purchase was essentially restricted to private land or very specific permitted zones.

These legislative hurdles created a massive deterrent for potential buyers who wanted to use the Segway for their daily commute to work or the shops. It is incredibly difficult to sell a transport revolution when the act of using it could result in a fine or the confiscation of the equipment by the police. While the company spent millions on lobbying efforts to change these laws, the progress was slow and inconsistent across different regions and countries. The lack of a clear legal framework meant that the Segway remained a legal curiosity rather than a practical tool, and by the time some regulations were relaxed, the public’s interest had already begun to wane in favour of other emerging technologies.

The Mall Cop Image

The cultural perception of the Segway took a definitive turn for the worse when it became synonymous with security guards and the “Mall Cop” stereotype. Instead of being seen as a sleek and futuristic transport solution for the stylish urbanite, the device became the preferred vehicle for private security patrolling shopping centres and airports. This association was solidified in the public consciousness by films like Paul Blart: Mall Cop, which used the Segway as a comedic prop to highlight the perceived laziness or self-importance of the character. Once a piece of technology becomes a punchline in mainstream media, it is almost impossible to regain its status as a desirable or “cool” consumer product for the general public.

This image problem was devastating because the Segway relied on a “cool factor” to justify its high price and unusual appearance to the world. Younger generations who might have embraced a new form of mobility were put off by the dorky aesthetic and the upright, stiff posture required to operate the machine. It looked inherently ungraceful compared to a skateboard or a bicycle, and the lack of physical effort involved in its operation led to a perception that it was a gadget for those unwilling to walk. The brand became trapped in a niche market of utility and novelty tours, losing its chance to ever become a lifestyle brand that people would be proud to display in their daily lives.

Tragic Leadership Change

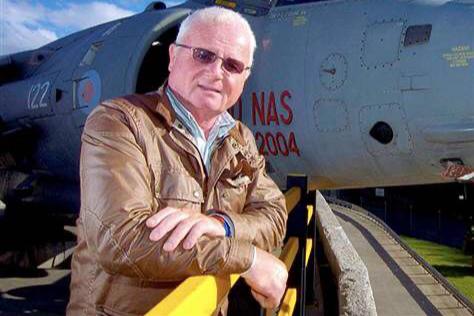

In a dark twist of irony, the history of the Segway is overshadowed by the tragic death of the man who bought the company in 2009. Jimi Heselden, a wealthy British businessman and philanthropist, took over the firm with hopes of revitalising the brand and expanding its reach across Europe and beyond. However, just ten months after the acquisition, he died in a freak accident while riding a rugged, off-road version of the Segway on his estate in West Yorkshire. He reportedly lost control and fell over a cliff into a river, a tragedy that sent shockwaves through the tech world and cast a permanent, somber shadow over the reputation of the device’s safety.

While the accident was a personal tragedy, the media coverage inevitably linked the death of the owner to the inherent dangers of the product he was trying to sell. It was a PR nightmare that the company could never truly recover from, as it reinforced the public’s underlying fears about the stability and reliability of self-balancing technology. Even though the Segway was generally considered safe when used correctly, the headline of the “Segway Boss Killed by Segway” was too sensational for the public to ignore. This event marked the beginning of a long decline for the original PT model, as the company struggled to find its footing and a clear sense of purpose in the wake of such a high-profile loss.

Niche Tourism Dominance

As the dream of personal commuting faded, the Segway found an unexpected and enduring home in the world of urban tourism and guided city tours. If you visit any major capital city today, you are likely to see a string of tourists wobbling along behind a guide on these two-wheeled machines. This pivot allowed the company to stay afloat by selling fleets of devices to tour operators who could justify the high cost through rental fees. For many people, a Segway tour became a “bucket list” activity—a fun, one-off novelty that allowed them to see the sights without the physical exhaustion of walking miles across a cobblestoned European city.

However, becoming a tourist attraction was a double-edged sword for the brand’s long-term viability as a transport solution. While it provided a steady stream of revenue, it further cemented the idea that the Segway was a toy for holidays rather than a serious vehicle for daily life. Most people who enjoyed a Segway tour had no intention of actually buying one for themselves once they returned home to their normal routines. The device became a “once-in-a-lifetime” experience rather than a daily habit, and the market for tour fleets was eventually saturated. This niche success kept the lights on at the factory, but it was a far cry from the global mobility revolution that had been promised at the launch.

The Ninebot Acquisition

In 2015, the American Segway brand was acquired by its Chinese rival, Ninebot, a move that many saw as the final admission that the original business model had failed. Interestingly, Ninebot had previously been accused by Segway of patent infringement, making the buyout a classic “if you can’t beat them, buy them” scenario. This acquisition marked a massive shift in direction for the brand, moving away from the expensive and bulky PT models toward more affordable and portable electric mobility solutions. The new leadership recognised that the future lay in smaller, lighter devices that could be easily integrated into a modern lifestyle, rather than the heavy-engineered marvels of the past.

Under Ninebot’s ownership, the Segway name was preserved as a premium badge, but the technology inside began to change rapidly to meet market demands. They focused on building a broader ecosystem of products, including go-karts, self-balancing skates, and most importantly, the kick-scooters that would eventually take over the world. This transition allowed the company to survive the “death” of its flagship product by pivoting to the very trend that the original Segway had paved the way for. It was a pragmatic move that saved the company from total bankruptcy, even if it meant the original vision of the upright, large-wheeled transporter had to be quietly retired from the main stage.

The Rise Of E-Scooters

The ultimate irony of the Segway story is that the “scooter revolution” finally happened, but it looked nothing like the original Segway PT. Instead of a five-thousand-dollar self-balancing machine, the world embraced the lightweight, folding electric kick-scooter that could be rented for a few pounds via a smartphone app. Companies like Lime and Bird used the foundational battery and motor technology developed by firms like Segway-Ninebot to flood cities with thousands of accessible scooters. These devices solved the price and portability problems that had plagued the original Segway, finally providing the “last mile” solution that Dean Kamen had envisioned decades earlier but in a much more practical form factor.

Segway-Ninebot actually became the primary manufacturer for many of these ride-sharing giants, meaning the company finally achieved mass adoption, just not with the product they expected. The electric kick-scooter was cheaper to produce, easier to ride, and much less socially awkward than the original Segway. It could be folded up and taken on a train or stored under a desk, making it a genuine tool for the modern commuter. The success of the e-scooter validated the original idea that people wanted electric personal transport, but it also proved that the execution of the Segway PT was fundamentally flawed for the needs of the general public.

Discontinuation Of The Original

In June 2020, the company officially announced that it would stop production of the Segway PT, the iconic upright vehicle that started it all. By the time it was retired, the PT accounted for less than three percent of the company’s total revenue, a clear indication that the world had moved on to other things. The factory in Bedford, New Hampshire, which had once been the site of so much hope and ambition, shifted its focus to other products within the Ninebot portfolio. It was the end of an era for a machine that had become one of the most famous, yet least successful, inventions of the twenty-first century.

The discontinuation was met with a mix of nostalgia and pragmatism from the tech community and the general public alike. For many, it felt like the closing of a chapter on a specific kind of early-2000s optimism where we thought hardware alone could fix the world. The company admitted that the durability of the machines was actually part of the problem; they were built so well that they rarely needed replacing, which is a terrible business model for a luxury consumer good. As the final units rolled off the assembly line, the Segway PT took its place in history as a brilliant piece of engineering that simply couldn’t find its place in the messy reality of the human world.

Legacy In Modern Robotics

Although the Segway PT is no longer in production, its DNA lives on in some of the most advanced robotics and self-balancing systems in the world today. The complex algorithms and gyroscopic sensors developed for the Segway paved the way for a new generation of robots that can navigate human environments with ease. From warehouse robots that carry heavy loads to delivery bots that roam the pavements of London and San Francisco, the “dynamic stabilisation” technology pioneered by Dean Kamen is everywhere. The Segway wasn’t just a scooter; it was a masterclass in how to make a machine stay upright on two wheels, a problem that had baffled engineers for decades.

Furthermore, the Segway’s failure provided invaluable lessons for the modern “micromobility” industry regarding regulation, safety, and public perception. Today’s e-scooter companies are much more proactive in working with city councils and urban planners because they saw the “Segway wall” and knew they had to climb over it. The dream of a car-free city is still alive, and it is being built on the foundations of the research and development that went into that original, failed experiment. We may not be gliding around on Segways, but the electric, two-wheeled future we were promised is slowly becoming a reality in a way that is far more integrated and useful.

The Lasting Impact On Micromobility

While the original Segway PT might have vanished from our high streets, its influence is stitched into the fabric of the modern micromobility movement that defines our cities today. Before Dean Kamen’s invention, the idea of a high-tech, battery-powered alternative to the car for short urban journeys was largely the stuff of science fiction and niche hobbyist magazines. The Segway acted as a pioneer that broke the ground for the legal and social acceptance of personal electric vehicles, even if it had to suffer the initial arrows of ridicule and restrictive legislation itself. Today’s bustling fleets of hireable e-scooters and electric bikes owe a massive debt to the research, development, and public debates that were sparked by that original upright transporter back in the early 2000s.

The legacy of the brand now lives on through a much more diverse and practical product range that actually meets the needs of a wider demographic of users. By moving away from the “one-size-fits-all” approach of the heavy PT model, the company has managed to successfully integrate into the daily lives of millions of people worldwide. We now see a world where the “last mile” problem is being solved by a variety of form factors, all of which benefit from the motor efficiency and battery management systems pioneered by the original Segway engineers. It is a classic case of an invention failing so that an entire industry could eventually succeed, proving that being first is often less important than being the most adaptable in a rapidly changing world.

Lessons For The Future Of Transport

The ultimate lesson of the Segway’s journey is that technology alone cannot dictate the future of how we move unless it aligns with the existing infrastructure of our society. The machine was a victim of being too far ahead of its time, arriving long before our cities were designed with dedicated lanes for small, low-speed electric vehicles. Its story serves as a cautionary tale for today’s tech giants who are currently pouring billions into autonomous cars and flying taxis, reminding them that human habit and urban planning are far more difficult to change than software or hardware. To truly revolutionise transport, an invention must be as socially seamless as it is technically impressive, fitting into the gaps of our lives rather than demanding we rebuild our entire world to accommodate it.

Looking back, we can see that the Segway was not a failure of imagination but perhaps a failure of perspective regarding what the average person actually wants from a commute. People did not want a five-thousand-pound status symbol that required a dedicated parking space and a steep learning curve to master safely. They wanted something simple, affordable, and unobtrusive that could get them from the train station to the office without a fuss or a heavy financial burden. As we reflect on the implications of relying on one factory and one vision, it becomes clear that the most successful transport solutions are those that offer flexibility and accessibility above all else. The Segway may have flopped, but it paved the way for a quieter, greener, and more mobile world that we are only just beginning to fully inhabit.

In the end, it wasn’t the technology that failed, but the business’s ability to adapt to how humans actually live and move.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.