1. Half Cent Coin

The half cent was one of the very first coins ever authorized by the United States government under the Coinage Act of April 2, 1792. It officially entered production in 1793 and remained a part of American pockets for over sixty years. Back then, the economy was much smaller, and even a fraction of a cent had real purchasing power. You could actually buy basic household goods or pay for local services with these small copper pieces. They were essential for a young nation where every bit of metal counted, and people relied on them for exact change in a world before modern inflation made such tiny amounts seem trivial.

However, as the mid-19th century approached, the American economy began to change rapidly. Prices started to rise, and the cost of minting these pure copper coins began to outweigh their actual value. By the time 1857 rolled around, Congress decided the half cent had finally outlived its usefulness. On February 21, 1857, a law was passed that officially discontinued the coin. Today, looking at a half cent feels like looking at a different world, one where Americans meticulously tracked every tiny fraction of their wealth. Its retirement was a major sign that the U.S. was moving toward a faster, more industrial future where convenience started to matter more than tiny, physical calculations.

2. Two Cent Coin

The two cent coin is a fascinating piece of Civil War history, first appearing in 1864. At the time, the United States was deeply divided by war, and people were so nervous about the future that they began hoarding silver and gold coins. This created a massive shortage of small change, making it hard for shops to stay open. To solve this, the government introduced the two cent piece. Beyond its practical use, this coin holds a special place in history because it was the very first piece of U.S. currency to feature the motto “In God We Trust.” This phrase was added during the height of the war to provide a sense of national unity and spiritual comfort.

While the coin was a lifesaver during the 1860s, its popularity didn’t last very long after the war ended. Once the national crisis passed and other coins like the nickel became more common, people found they didn’t really need a two cent denomination anymore. It felt awkward to use and often got confused with other coins. By 1873, the Mint decided to stop making them for good. Even though it only circulated for about nine years, the two cent coin remains a powerful symbol of a time when the government had to get creative to keep the economy moving during its darkest hours.

3. Three Cent Silver

The three cent silver coin, often called the “trime,” was introduced in 1851 for a very specific reason: the price of postage stamps. That year, the cost of mailing a letter was lowered from five cents to three cents, and the government realized they didn’t have a single coin that could pay for a stamp exactly. To make life easier for the public, they minted this tiny silver coin. It was incredibly thin, actually the thinnest silver coin the U.S. has ever produced, and was made of 75% silver and 25% copper. It was so small and light that people often complained about losing them through the cracks in their pockets or accidentally dropping them.

Despite being very useful at the post office, the “trime” faced many challenges. Because it was so small, it was difficult to handle, and as the Civil War broke out, people began hoarding them just like they did with other silver coins. To fix this, the government eventually created a version made of nickel, which made the silver version redundant. By the time the Coinage Act of 1873 was passed, the three cent silver piece was officially retired. Today, collectors see it as a delicate, almost fragile reminder of a time when currency was designed to solve very specific, everyday problems like sending a simple piece of mail.

4. Three Cent Nickel

Following the struggle with the tiny silver version, the U.S. Mint introduced the three cent nickel in 1865. This coin was made of a mix of copper and nickel, making it much larger, sturdier, and harder to lose than its silver predecessor. It was released just as the Civil War was ending and was intended to help replace the “fractional” paper money that people hated using for small purchases. For a while, it worked quite well, and millions of these coins were minted to help get the economy back on its feet during the Reconstruction era. It was a durable solution for a public that was tired of flimsy paper coins.

However, the three cent nickel eventually ran into a “middle child” problem. Its value was stuck awkwardly between the one cent penny and the five cent nickel, which was becoming the new standard for small change. As the 1880s rolled on, the demand for three cent pieces plummeted because people simply preferred using a combination of pennies and five cent nickels. The Mint realized they were wasting resources on a coin nobody wanted, so they officially stopped production in 1889. Its disappearance showed that even if a coin is well-made and durable, it won’t survive if it doesn’t fit into the natural rhythm of how people like to spend their money.

5. Twenty Cent Coin

The twenty cent coin is often remembered as one of the biggest “flops” in the history of the U.S. Mint. Introduced in 1875, it was supposed to help people in the Western United States. Out West, people used a lot of Mexican silver coins, and there was a constant shortage of small change. The government hoped a twenty cent piece would make transactions easier by providing a mid-point between a dime and a quarter. On paper, it seemed like a smart economic move to bridge the gap in regional trade, but in reality, it caused nothing but headaches for the average American shopper.

The biggest problem was that the twenty cent coin looked almost exactly like the quarter. It was roughly the same size, made of the same silver material, and featured a very similar “Seated Liberty” design. People were constantly getting confused, accidentally paying twenty-five cents for something that only cost twenty, or vice-versa. The public grew frustrated with the constant mistakes, and the coin became widely disliked almost immediately. After only two years of general production, the government gave up and stopped making them for circulation in 1878. It remains one of the shortest-lived coins in American history, serving as a permanent lesson for the Mint that visual clarity is just as important as the value of the money itself.

6. Gold Dollar Coin

The gold dollar was a product of one of the most exciting times in American history: the California Gold Rush. After gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill in 1848, the U.S. was suddenly flooded with the precious metal. To put all that new wealth to use, Congress authorized the gold dollar in 1849. It was a beautiful, tiny coin that represented a high value in a very small package. At a time when a dollar could buy a significant amount of food or supplies, having a gold version felt prestigious. It was produced in three different designs over the years, becoming a staple of mid-19th-century commerce.

However, the coin’s greatest strength was also its greatest weakness. Because it was made of gold, it had to be very small to equal exactly one dollar in value. It was actually the smallest coin in U.S. history, even smaller than a modern dime. People complained constantly that the coins were too easy to lose or drop. As paper “Greenbacks” became more popular during and after the Civil War, people grew more comfortable with paper dollars and less interested in fumbling with tiny gold specks. The Mint finally stopped making them in 1889. Today, they are prized by collectors, representing a golden era when the literal value of a coin was found in the metal itself.

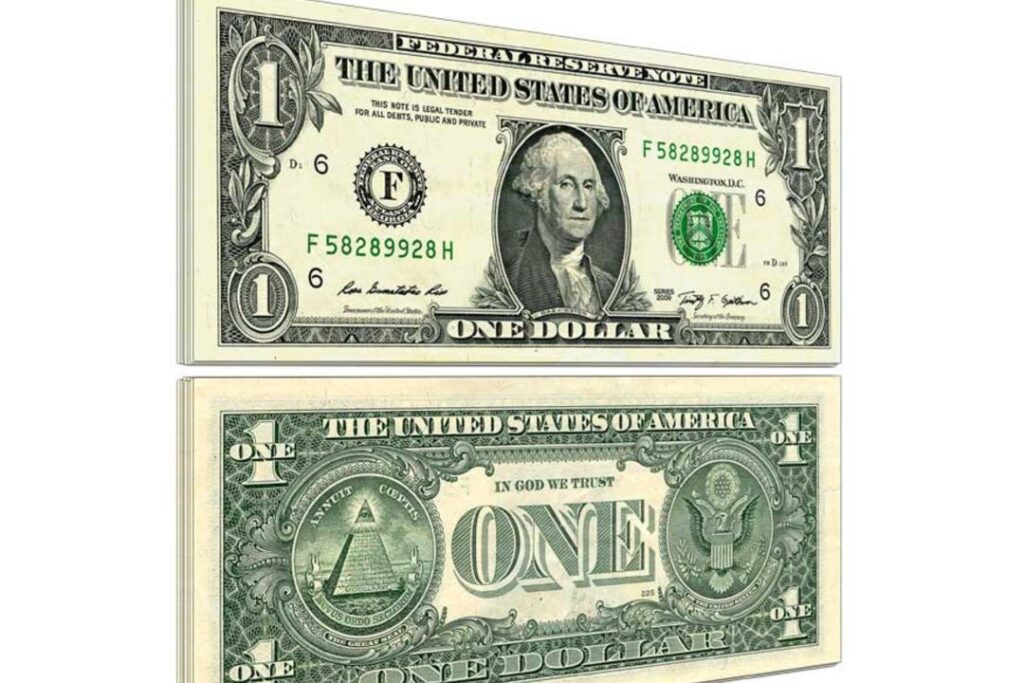

7. Large Size One Dollar Bill

If you traveled back in time to the early 1900s, you would notice something very strange about the money in people’s wallets: it was huge. Before 1929, U.S. paper currency was about 30% larger than the bills we use today. These notes were often nicknamed “horse blankets” because of their massive size. They weren’t just bigger; they were also incredibly beautiful. These large-size one dollar bills featured highly detailed artwork, intricate engravings, and grand portraits of historical figures like George Washington or even Martha Washington. They felt more like pieces of fine art than simple pieces of paper used to buy groceries.

The change to our modern, smaller size happened in 1929 as a way for the government to save money. By shrinking the bills, the Treasury could print more notes using less ink and paper, which was a huge deal during the start of the Great Depression. The smaller “small-size” notes were also easier to fit into standard wallets and more convenient for banks to handle. While the value stayed the same, the “horse blankets” were gradually pulled out of circulation and destroyed. Seeing one today is a reminder of a time when the United States took great pride in the physical grandeur of its currency, treating every single dollar bill like a masterpiece of national identity.

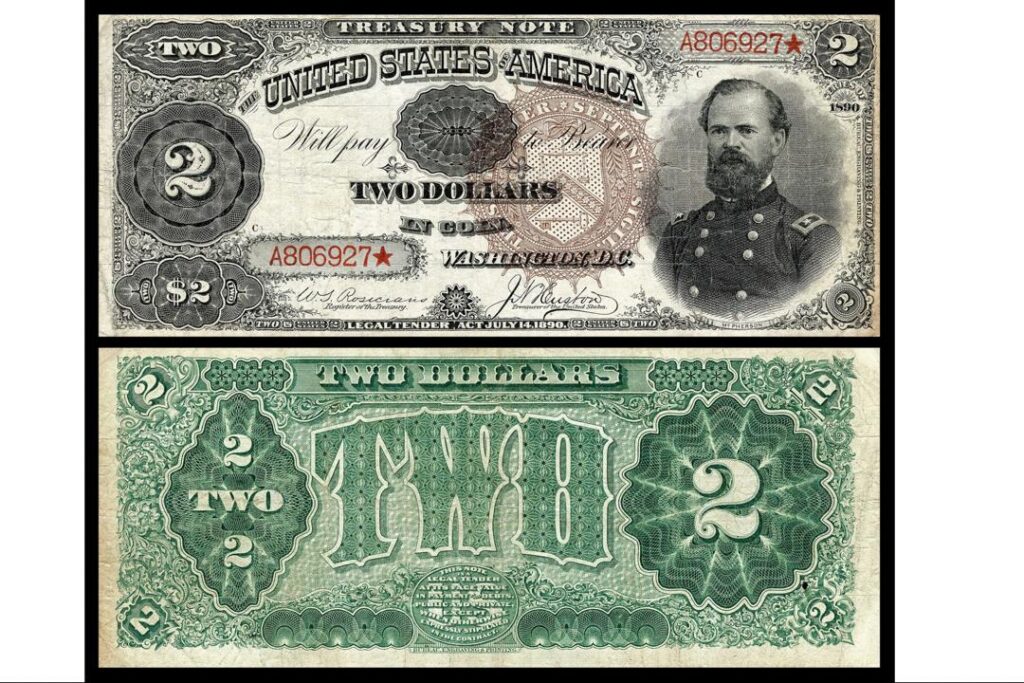

8. Two Dollar Treasury Note

The two dollar Treasury note is a unique piece of history that is often confused with the two dollar bills we see occasionally today. These specific notes, issued mostly in the 1890s, were known as “Coin Notes.” What made them special was that they were backed directly by the government’s holdings of silver and gold bullion. If you held one of these, the law actually allowed you to walk into a Treasury office and demand to be paid in actual silver or gold coins. This gave people a great deal of confidence in the money during a time when the economy was often unstable and prone to sudden panics.

These notes featured some of the most beautiful and complex designs ever seen on American money, including portraits of famous figures like James McPherson. However, as the 20th century began, the government started moving toward a more centralized banking system. The need for these specific “Coin Notes” faded as the new Federal Reserve system took over the job of printing money. By the 1930s, the Treasury stopped issuing them altogether. While they are still technically legal tender today, they are worth much more to history buffs and collectors. They represent a bridge between the old world of metal-backed money and the modern world of “fiat” currency, where the value is based on the government’s word.

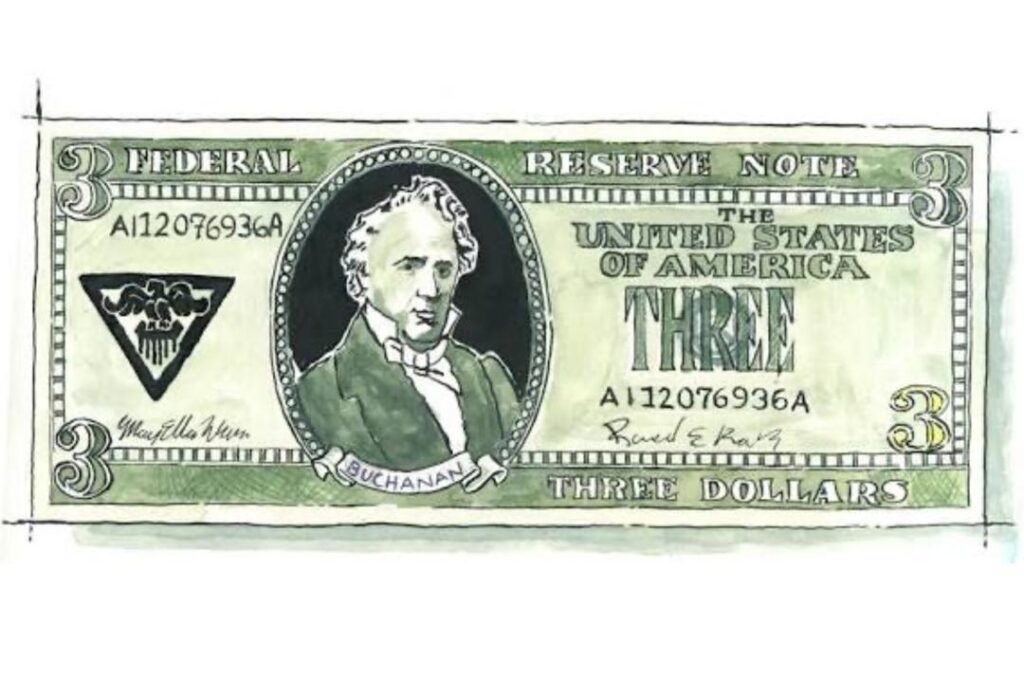

9. Three Dollar Bill

You have probably heard the old saying “as phony as a three dollar bill,” but for a few decades in the 19th century, three dollar bills were actually very real. Between the 1860s and the 1880s, these notes were issued by various banks and even the government to help with specific needs. One reason they were created was to make it easier for people to buy sheets of three-cent stamps, which were standard at the time. They were also used to help fill gaps when there weren’t enough coins to go around. They featured interesting designs, often including images of historical figures or scenes of American industry.

Despite being official, the three dollar bill never quite felt “right” to the American public. People found the math confusing, and it was hard to make change for a three dollar note using the existing coins. Most people preferred to just use three one dollar bills instead. Because they weren’t popular, they were never printed in massive quantities, and the government eventually decided to stop producing them as the currency system became more standardized in the late 1800s. Today, the three dollar bill is a legendary piece of Americana. It reminds us that what we consider “normal” money is really just a matter of habit, and at one point, a three dollar note was just as valid as a five.

10. Gold Certificates

Gold certificates were a very special type of paper money used in the United States from 1863 until 1933. Unlike the regular money we use now, these notes were essentially a “receipt” for actual gold. If you had a twenty dollar gold certificate, it meant there was twenty dollars’ worth of pure gold sitting in a vault at the U.S. Treasury with your name on it. These bills were famous for their vibrant orange or gold-colored backs and bright yellow seals, which made them stand out from every other type of currency. They were a symbol of wealth and stability, used by both regular people and large banks.

The era of the gold certificate came to an abrupt end during the Great Depression. In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102, which required Americans to turn in their gold and gold certificates to the government in an effort to stabilize the national economy. It actually became illegal for citizens to hold these notes for a long time. The U.S. officially moved away from the “gold standard,” and the certificates were replaced by Federal Reserve notes that weren’t tied to metal. While the ban on owning them was eventually lifted in the 1960s, they never returned to circulation. They remain a striking visual reminder of a time when every paper dollar was a promise of real, physical gold.

11. Silver Certificates

Silver certificates were a staple of American life for nearly a century, first authorized by the Bland-Allison Act on February 28, 1878. These notes were unique because they weren’t just “paper”; they were essentially a contract. If you held a five-dollar silver certificate, the law guaranteed that you could walk into a bank and exchange it for five dollars’ worth of physical silver coins or bullion. This gave people, especially those in rural farming communities, a deep sense of security. They knew their money was backed by something they could see, feel, and weigh. Most of these notes are easily recognized by their distinct blue seals and serial numbers, which set them apart from the green or red seals found on other bills.

As the 20th century progressed, the price of silver began to rise significantly, making it more expensive for the government to maintain this exchange. In the early 1960s, the demand for silver grew so high that the government decided to phase out the certificates. On June 24, 1968, the official period for redeeming these notes for silver ended forever. While you can still spend a silver certificate at a store today for its face value, they are worth much more to collectors. Their retirement marked the final step in the U.S. moving away from metal-backed money toward the modern system we use today, where value is based on national trust.

12. United States Notes

United States Notes, famously known as “Legal Tender Notes” or “Greenbacks,” have a history that dates back to the dark days of the Civil War. First issued under the Legal Tender Act of February 25, 1862, they were the first national paper currency not backed by gold or silver. Instead, they were backed only by the “good faith” of the United States government. They were created because the government desperately needed a way to pay for the war effort without relying on scarce metal coins. You can usually spot these historic notes by their bright red seals and red serial numbers, which gave them a very bold and official appearance compared to other currency of the era.

For over a hundred years, these notes circulated right alongside the Federal Reserve notes we use today. However, having two different types of similar-looking money was confusing and unnecessary for the modern economy. In 1971, the Treasury Department decided to stop issuing them to simplify the national currency system. While the government officially “retired” them from production, they are still technically legal tender. If you found one in an old attic, you could legally spend it at a grocery store, though a collector would likely pay you much more for it. They represent a successful experiment in government-issued money that helped save the Union during its most difficult hour.

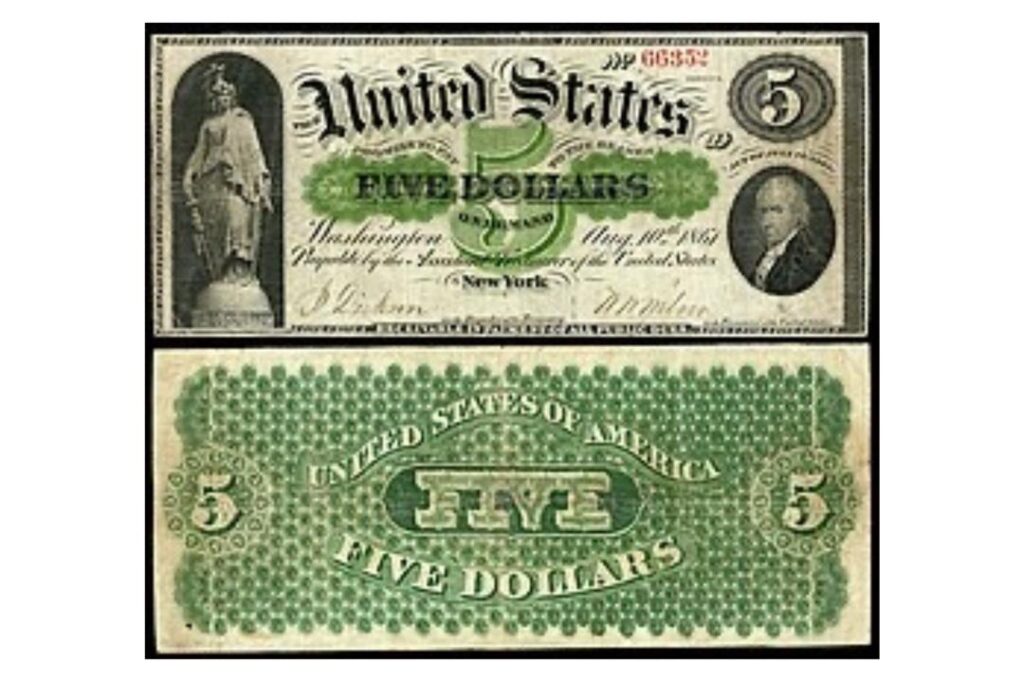

13. Demand Notes

Demand Notes were the very first high-volume paper money issued by the U.S. federal government, appearing in 1861. Before this, most people only ever saw coins or notes issued by private local banks. Because the Civil War was draining the Treasury’s supply of gold and silver, the government needed a way to pay soldiers and suppliers immediately. These notes were called “Demand Notes” because the government promised to pay the holder in coin “on demand” at certain Treasury offices. Because they featured green ink on the back to prevent counterfeiting, they earned the nickname “Greenbacks,” a term that we still use for American dollars more than 160 years later.

These notes were only issued for a very short time, from August 1861 to April 1862. Their design was quite plain compared to later bills because they were produced in a great hurry to meet the needs of a country at war. They didn’t even have the official Treasury Seal that we see on modern money today. Once the government introduced the more permanent United States Notes in 1862, the Demand Notes were quickly pulled out of circulation and destroyed. Today, they are incredibly rare and highly sought after by historians. They serve as a fascinating reminder of a time when the U.S. government had to improvise its entire financial system almost overnight to survive a national crisis.

14. Fractional Currency

During the Civil War, something strange happened: small silver and copper coins completely vanished from daily life. People were so worried about the war that they hoarded every coin they could find, leaving shopkeepers with no way to make change for customers. To solve this “coin famine,” the government introduced Fractional Currency in 1862. These were tiny paper bills in denominations of 3, 5, 10, 15, 25, and 50 cents. Imagine going to a store today and being handed a tiny piece of paper instead of a nickel or a dime! At first, people even used actual postage stamps for change, which led the government to formalize these “paper coins.”

Fractional currency was issued in five different series between 1862 and 1876. While they were a lifesaver for the economy during the war, they weren’t very popular in the long run. The paper was thin and easily damaged, and because the notes were so small, they were very easy to lose. Once the war ended and the mints were able to produce enough metal coins again, the public was happy to go back to “real” change. Congress officially authorized the redemption of these notes for coins in 1876, and they quickly faded away. They remain one of the most unusual chapters in American money, showing how a country can adapt when even the simplest things, like a penny, become scarce.

15. Half Dime

Long before the modern nickel was introduced in 1866, the five-cent piece of choice was the “half dime.” These were tiny coins made of real silver, first authorized by the Mint Act of 1792. They were much smaller and thinner than the nickels we carry today, so small that they were often called “fish scales” by the public. Because they were made of silver, they held a lot of value for their size, and they were used constantly in early American commerce. From 1794 until the early 1870s, the half dime was the backbone of small transactions, helping people buy everything from a loaf of bread to a local newspaper.

The half dime’s downfall came after the Civil War. The government realized that using silver for such a small denomination was becoming too expensive. In 1866, they introduced the five-cent “nickel” made of a copper-nickel alloy, which was larger, cheaper to make, and much easier for people to handle without dropping. For a few years, both the silver half dime and the copper-nickel five-cent piece circulated at the same time. However, the Mint eventually decided it didn’t need two different coins for the same value. The Coinage Act of 1873 officially ended the production of the silver half dime. Today, these elegant little coins are reminders of an era when even our smallest change was made of precious, shimmering silver.

16. Trade Dollar

The Trade Dollar is one of the most unique coins ever produced by the United States because it wasn’t actually meant to be used in America. Introduced in 1873, it was specifically designed to compete with the Spanish dollar in international trade, particularly in East Asia. Merchants in China and Japan preferred silver coins of a very specific weight and purity, so the U.S. Mint created a coin that contained slightly more silver than a standard American dollar. To make them official, these coins were stamped with their weight and fineness right on the back. For a few years, they were a common sight in busy ports across the Pacific Ocean.

Domestically, however, the Trade Dollar caused a lot of trouble. Because they contained more silver, they were technically worth more than a regular dollar, but many people in the U.S. tried to use them for everyday purchases at face value. This led to massive confusion and even a bit of a scandal when the price of silver dropped, making the coins worth less than a dollar in some places. In 1876, Congress took away their status as “legal tender” within the United States, making them the only U.S. coin to ever be officially “demonetized.” Production finally stopped in 1885. Today, they are prized by collectors as a symbol of America’s first big attempt to become a global economic superpower.

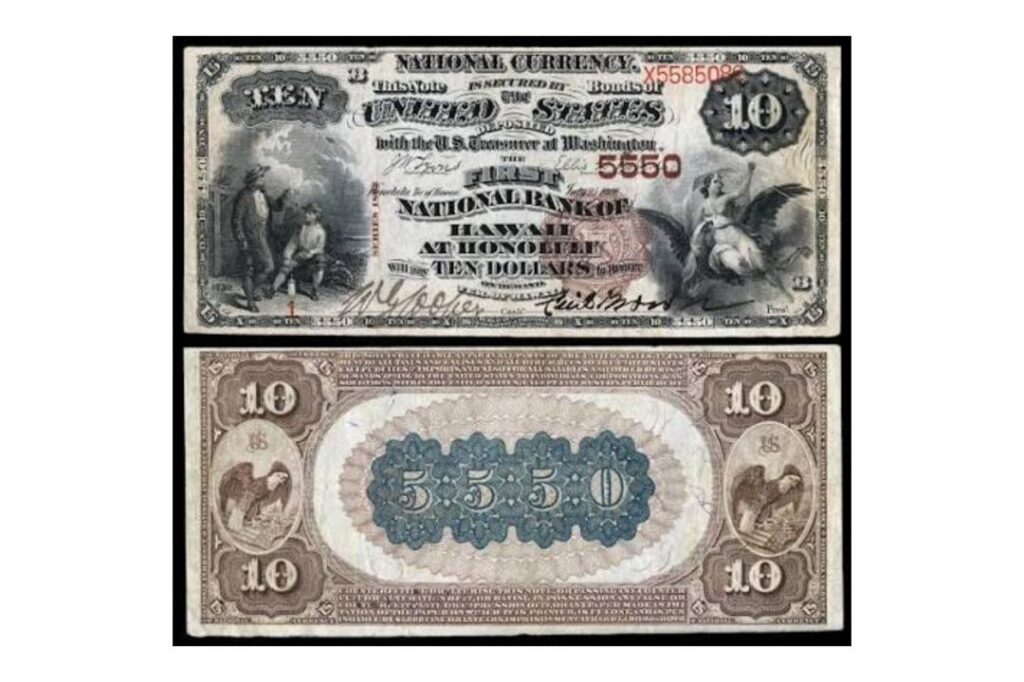

17. National Bank Notes

From 1863 until 1935, the United States used a very decentralized type of money called National Bank Notes. During this era, if a local bank met certain government requirements and bought U.S. bonds, it was allowed to issue its own paper currency. This meant that a person living in a small town in Ohio might carry bills that literally had the name of the “First National Bank of Dayton” printed on them. There were thousands of different banks across the country issuing their own unique versions of these notes. While they all looked somewhat similar to regular government money, each one had the specific signatures of the local bank’s president and cashier.

This system was great for local pride, but it was a nightmare for efficiency. As the American economy grew and people began traveling more between states, having thousands of different bank-branded bills made it very difficult for the government to track the money supply and prevent counterfeiting. When the Great Depression hit in the 1930s, the government decided it was time for a more unified system. In 1935, the authority for local banks to issue their own notes was officially ended, and they were replaced by the standard Federal Reserve notes we use today. These old bills are now historical treasures that tell the story of a time when banking was a much more local, community-focused business.

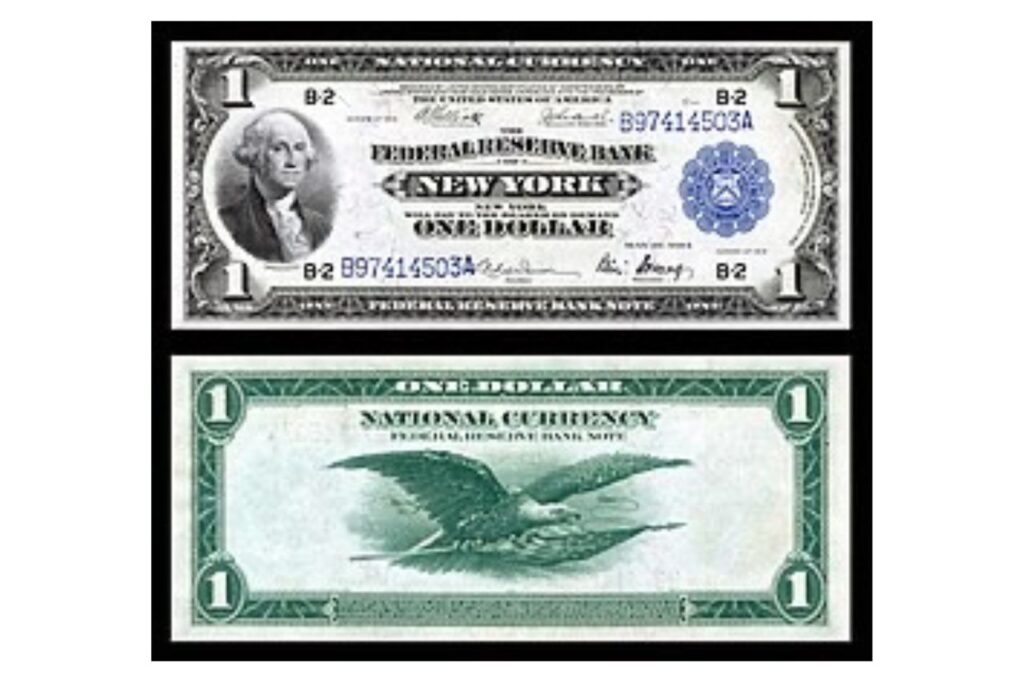

18. Federal Reserve Bank Notes

Federal Reserve Bank Notes are often confused with the “Federal Reserve Notes” we have in our pockets today, but they were actually quite different. Introduced in 1913 along with the creation of the Federal Reserve System, these notes were backed by the individual assets of the twelve different regional Federal Reserve Banks, rather than the U.S. Treasury as a whole. They were often used as “emergency” currency during times of financial stress. For example, during the Great Depression in 1933, the government issued a massive amount of these notes very quickly to ensure there was enough cash in the system while banks were being reorganized.

You can tell these notes apart from regular bills by the specific wording on the front, which names the individual city bank, like the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, that issued them. While they served a vital role in keeping the economy stable during several national crises, they were always intended to be a temporary solution. As the banking system became more modernized and streamlined, the government realized it was much more efficient to have just one single type of national currency. They were gradually phased out starting in the 1930s and were last issued in 1945. They represent a transitional period in American history when the country was still figuring out how to manage its massive, modern financial power.

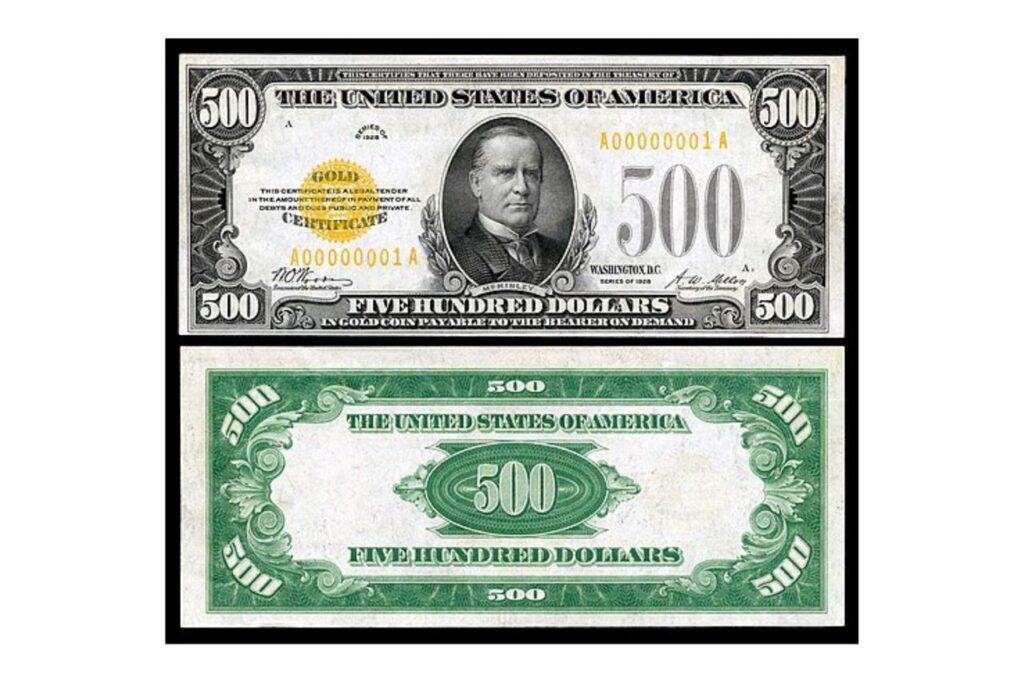

19. Five Hundred Dollar Bill

The $500 bill is a piece of currency that feels almost legendary to most people today. While it was once very real, it was never something the average person would carry in their wallet to buy bread or milk. Most of these high-denomination bills featured a portrait of President William McKinley and were used primarily for large-scale transactions between banks or for real estate deals before the age of digital wire transfers. If a bank needed to move a large amount of money to another branch, it was much easier to carry a few $500 bills than a giant bag filled with $1 notes.

The U.S. government actually stopped printing the $500 bill in 1945, though they continued to circulate for several more years. By the 1960s, the rise of electronic banking made these large bills unnecessary. Furthermore, the government was concerned that high-value notes were being used by criminals to hide large amounts of cash. On July 14, 1969, the Federal Reserve officially began pulling them out of circulation and destroying them as they returned to the banks. Even though they are still technically legal tender, they are now worth thousands of dollars to collectors. They remind us of a time when “big money” was something you could actually hold in your hand and lock in a safe.

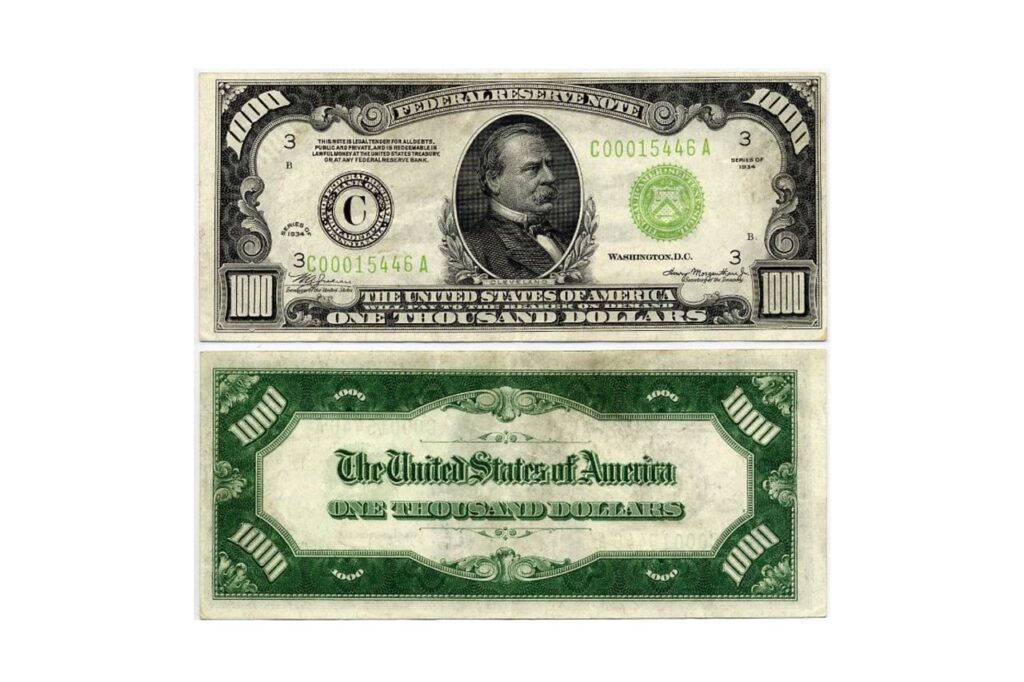

20. One Thousand Dollar Bill

Similar to the $500 note, the $1,000 bill was a “heavy hitter” of the American financial world. The most famous version featured a portrait of Grover Cleveland, the only U.S. President to serve two non-consecutive terms. These bills were almost exclusively used by wealthy individuals, large corporations, and banks for major payments. In the early 20th century, $1,000 was a massive fortune, equivalent to tens of thousands of dollars today, so seeing one was a rare event for most Americans. They were often used in the movies to show that a character was incredibly rich, which only added to their mysterious and glamorous reputation.

Just like its $500 cousin, the $1,000 bill was last printed in 1945. As technology improved, the need to physically move such large sums of money vanished. It became much safer and faster to use checks or electronic bank transfers than to risk carrying a piece of paper worth a small fortune. In 1969, the government officially ordered that these bills be retired to help combat organized crime and tax evasion. Today, the $1,000 bill is a holy grail for currency collectors. It represents the peak of physical currency in the United States, a time when value was massive, tangible, and beautifully engraved on a single piece of high-quality paper.

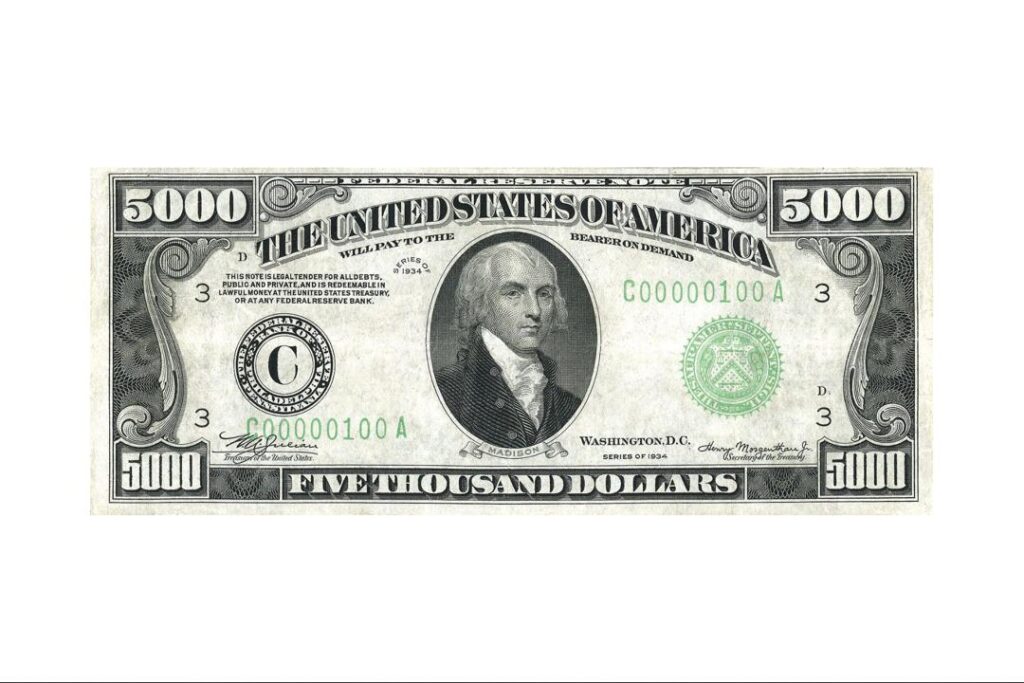

21. Five Thousand Dollar Bill

The $5,000 bill is one of the rarest pieces of American history, featuring a portrait of James Madison, the fourth U.S. President and the “Father of the Constitution.” These high-denomination notes were first introduced in 1861 and saw several design changes over the decades, with the most famous version being the Series of 1934. Because $5,000 was a massive fortune in the early 20th century, worth more than many people’s homes, these bills were almost never seen by the general public. Instead, they were used primarily by banks and the Federal Reserve to move large sums of money between institutions before the invention of modern computer networks.

By the mid-1940s, the government realized that printing such high-value notes was becoming a security risk. The last batch of these bills was printed in 1945, though they remained officially in use for a while longer. In 1969, due to a lack of use and concerns about organized crime, the Federal Reserve officially began withdrawing them from circulation. Today, there are only a few hundred of these notes known to still exist, and they are worth far more than their face value to collectors. They serve as a fascinating reminder of a pre-digital age when massive wealth had to be physically transported in leather satchels and locked in heavy steel vaults.

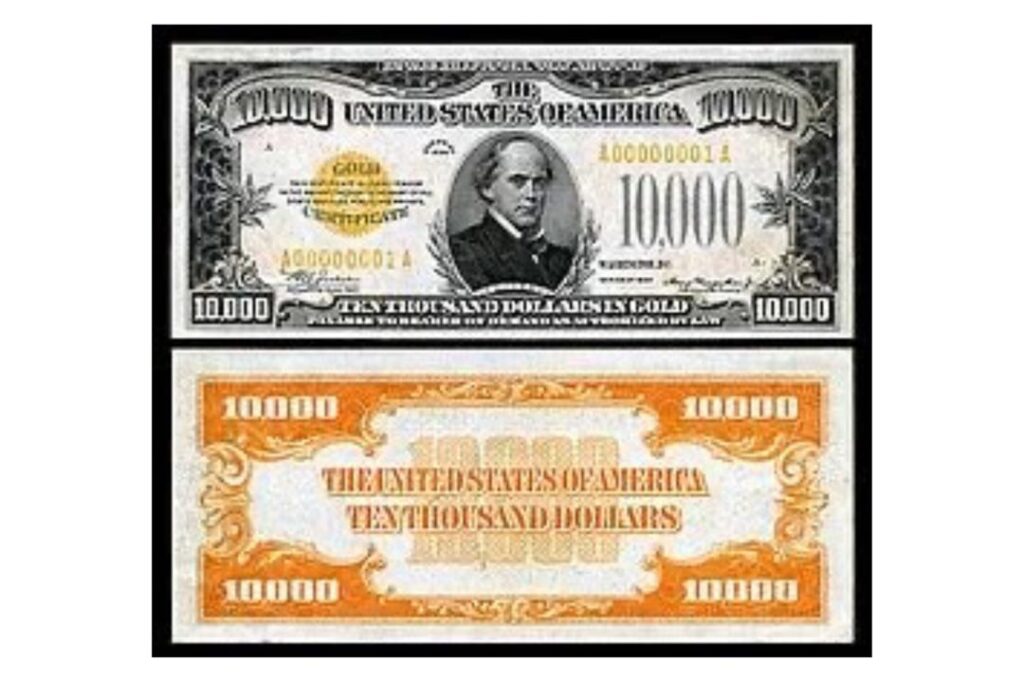

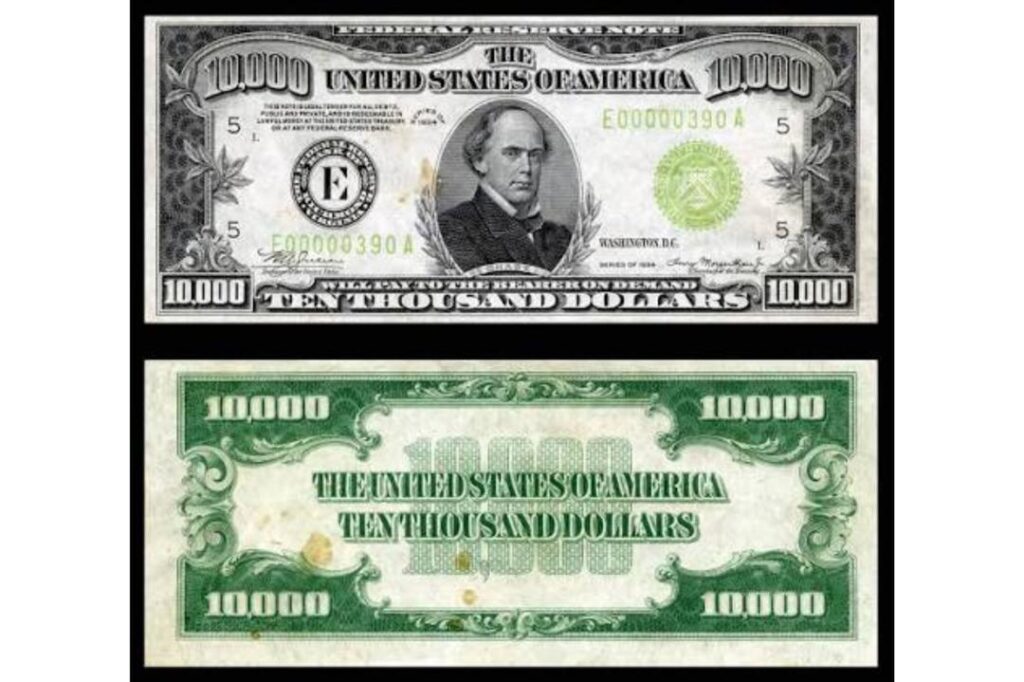

22. Ten Thousand Dollar Bill

The $10,000 bill holds the record for the highest denomination of U.S. currency ever intended for public circulation. It featured a portrait of Salmon P. Chase, who served as the Secretary of the Treasury under Abraham Lincoln. Interestingly, Chase was never a President, but he was the man responsible for the creation of our modern banking system. These notes were first issued in 1863, and while they were technically legal to use at a store, they were almost exclusively handled by banks for high-level accounting. In an era before wire transfers, a single $10,000 bill was the most efficient way to settle massive debts between major financial centers.

The printing of these “super-bills” officially ended in 1945. As the 1960s arrived, the government decided that the risks of keeping such high-value paper in circulation, such as money laundering or theft, far outweighed the benefits. On July 14, 1969, the $10,000 bill was officially retired alongside the $500 and $1,000 notes. Today, seeing one of these bills is a rare treat, often only possible in museums or high-end private collections. They represent the absolute peak of American paper currency, a time when a single piece of paper held enough value to change a person’s life forever, yet was rarely ever touched by common hands.

23. Gold Treasury Notes

Gold Treasury Notes, also known as “Coin Notes” of 1890 and 1891, were a unique and short-lived experiment in American finance. They were created because of a political battle between people who wanted the U.S. to use only gold and those who wanted to use silver. The government compromised by issuing these notes to pay for silver bullion that it was required to buy under the Sherman Silver Purchase Act. What made these notes special was that the holder could choose to be paid back in either gold or silver coins. This flexibility made them very popular with investors who wanted to protect themselves against the fluctuating prices of precious metals.

The life of these notes was cut short by the Panic of 1893, a massive economic depression. People became nervous about the government’s ability to pay, so they rushed to exchange their notes for gold, which nearly drained the U.S. Treasury’s gold reserves. To save the economy, Congress repealed the Silver Purchase Act, and the Treasury stopped issuing these specific notes shortly after. Most were gradually pulled from circulation and destroyed by the early 1900s. Today, they are prized by historians for their incredibly ornate and artistic designs, which are considered some of the most beautiful ever printed by the U.S. government, reflecting a time of intense political and economic debate.

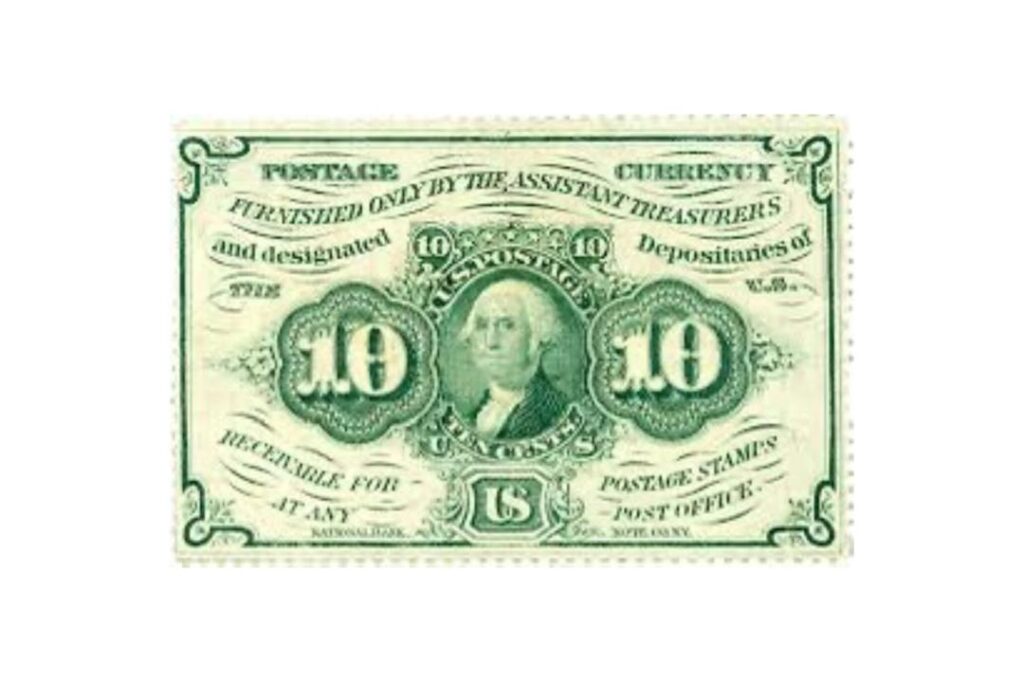

24. Postage Currency

Postage Currency was a truly desperate invention born from the chaos of the American Civil War in 1862. As the war intensified, people began hoarding every metal coin they could find, from pennies to half-dollars. This left merchants with absolutely no way to give change. In a moment of pure American ingenuity, people started using common postage stamps as money. However, stamps were sticky, small, and easily torn. Seeing this, the Treasurer of the United States, Francis Spinner, came up with the idea to print “Postage Currency”, small pieces of paper that looked like stamps but were actually official government money meant for spending.

This was the first time the U.S. government issued paper money in amounts less than a dollar. The first notes, issued in August 1862, even featured the designs of contemporary 5-cent and 10-cent stamps. While these tiny bills were a huge help to a country in crisis, they were only meant to be temporary. They were fragile and got dirty very quickly as they passed from hand to hand. By 1863, the government replaced them with a slightly more durable form called “Fractional Currency.” Though they only lasted a short time, Postage Currency proved that even in the middle of a war, the economy would find a way to keep moving, even if it meant turning stamps into cash.

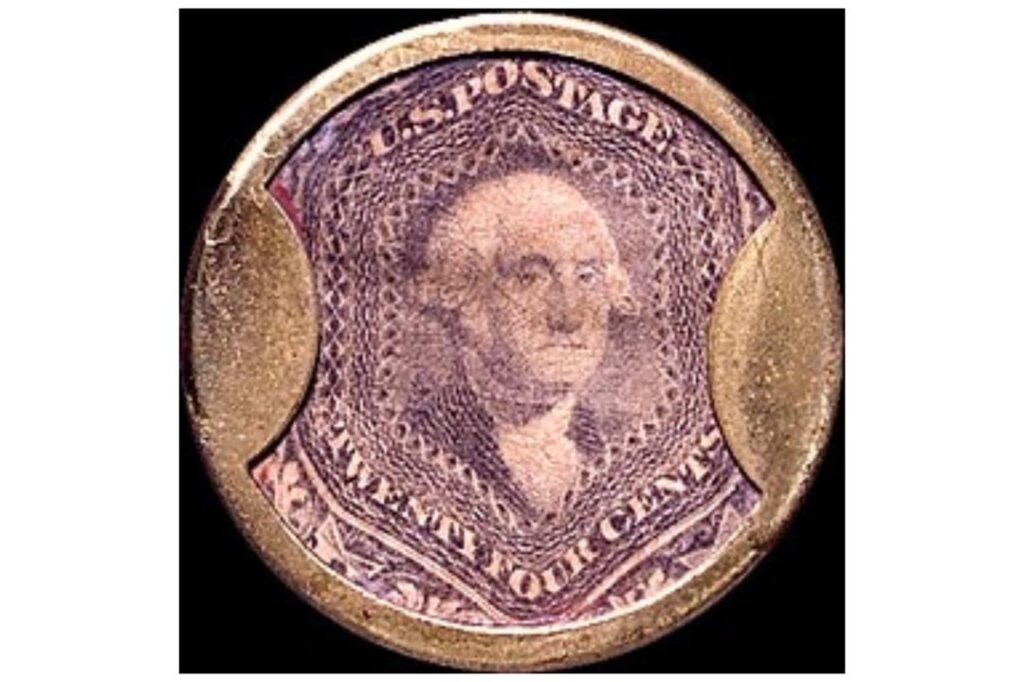

25. Encased Postage Stamps

Encased postage stamps are perhaps the most creative “emergency money” ever used in America. During the coin shortage of 1862, people were frustrated that regular paper stamps got dirty or stuck together when used as change. An inventor named John Gault came up with a brilliant solution: he took a standard postage stamp and sealed it inside a small, round brass frame with a clear mica window on the front. This protected the stamp and made it feel more like a real coin. On the back of the metal frame, businesses would often engrave advertisements for things like medicine, hotels, or dry goods, making them the first form of “sponsored” money.

These unique pieces of currency were used for a very brief period during the Civil War. They were actually quite expensive to produce because they required metal and mica, which were also in short supply. As soon as the government began issuing its own official paper “Fractional Currency,” the need for these privately made stamp-coins vanished. By the late 1860s, they had almost entirely disappeared from use. Today, encased postage stamps are highly valuable historical artifacts. They tell a story of a time when the American public and private businesses had to work together to find creative, hands-on solutions to keep daily life functioning while the nation was being torn apart by war.

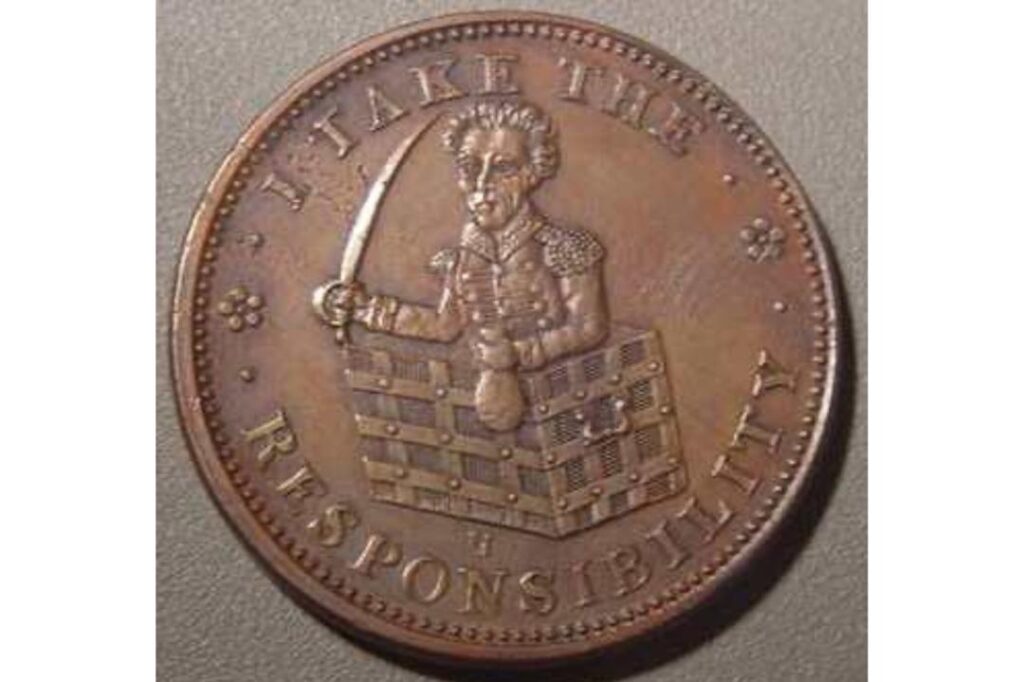

26. Hard Times Tokens

Hard Times tokens are a fascinating look at what happens when a country loses trust in its banks. These privately minted copper pieces circulated between 1833 and 1843, a period of severe economic depression in the United States. During this time, President Andrew Jackson was in a famous “war” with the Second Bank of the United States, which led to a massive shortage of official coins. To keep trade alive, private companies and political groups began minting their own “tokens” that were the same size as a large cent. People used them just like pennies to buy food and supplies when real government money was impossible to find.

What makes these tokens special is that they weren’t just money; they were also a form of protest. Many featured satirical political cartoons, such as images of a jackass labeled “LLD” to mock Andrew Jackson, or slogans like “Millions for Defence, Not One Cent for Tribute.” They were a way for the average person to carry their political opinions in their pocket. Once the economy began to recover in the mid-1840s and the government increased the production of official coins, these tokens were no longer needed. They remain a vivid reminder of a decade of financial struggle, showing that when the government fails to provide a stable currency, the people will take matters into their own hands.

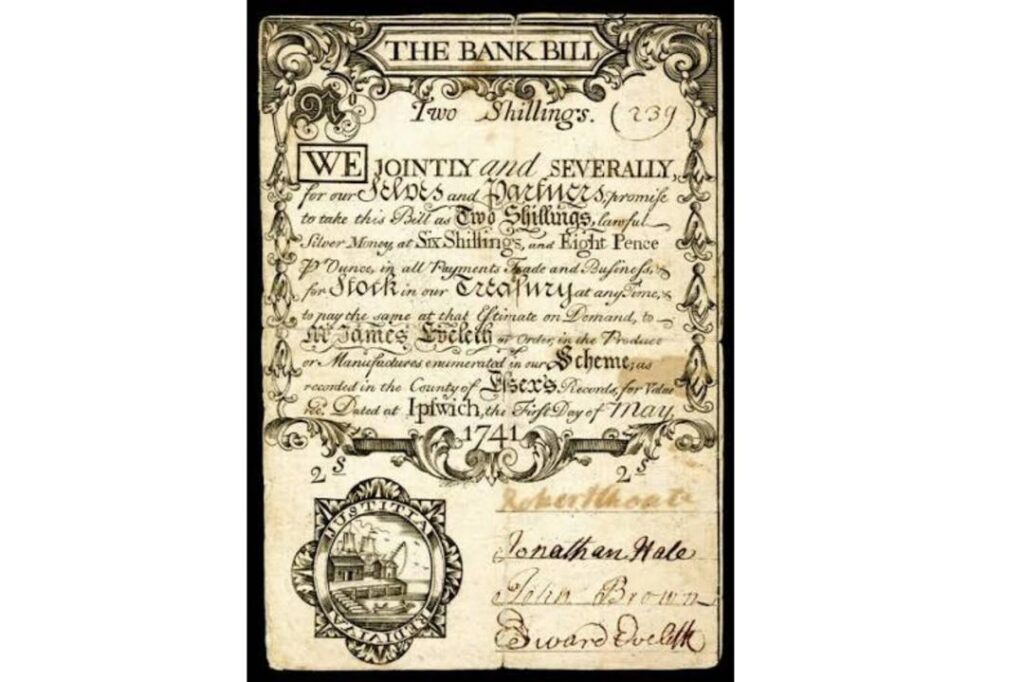

27. Colonial Paper Currency

Before the United States was even a country, the individual thirteen colonies were already experimenting with paper money. Starting with Massachusetts in 1690, each colony issued its own unique bills to pay for wars or public projects. These notes were often called “Bills of Credit” and were backed by the promise of future tax collections. Because there was no central government to set standards, the money from Virginia looked and felt completely different from the money used in New York. The designs were often simple, using woodblock prints and early security features like actual pressed leaves to prevent people from making fakes.

However, this system was very unstable. During the Revolutionary War, the colonies (and the new Continental Congress) printed so much paper money that it became almost worthless, leading to the famous saying “not worth a Continental.” When the U.S. Constitution was finally ratified in 1788, it specifically took away the power of individual states to print their own money. The old colonial notes were gradually traded in for new federal currency or simply kept as souvenirs. These early bills are the ancestors of the modern dollar, representing a time when the very idea of American money was a local, experimental, and often risky gamble on the future of a new land.

28. Confederate Currency

Confederate currency was the money issued by the Confederate States of America (CSA) during the Civil War, between 1861 and 1865. Because the South did not have much gold or silver, they printed massive amounts of paper money to fund their army and government. These notes are famous for their interesting artwork, often featuring scenes of Southern life, steamships, or portraits of leaders like Jefferson Davis. However, the money had a major flaw: it was essentially a “promissory note” that told the holder they would be paid in real money only if the South won the war and established a peaceful nation.

As the war dragged on and it became clear the Confederacy was losing, people lost all confidence in the currency. This led to “hyperinflation,” where prices rose so fast that a loaf of bread could cost hundreds of Confederate dollars. By the time the war ended in April 1865, the money was completely worthless, literally worth less than the paper it was printed on. Many people used the leftover bills as wallpaper or kindling for fires. Today, Confederate notes are popular with history buffs because they represent a specific, tragic era. They serve as a permanent lesson in economics: a currency is only as strong as the government that stands behind it and the trust of the people using it.

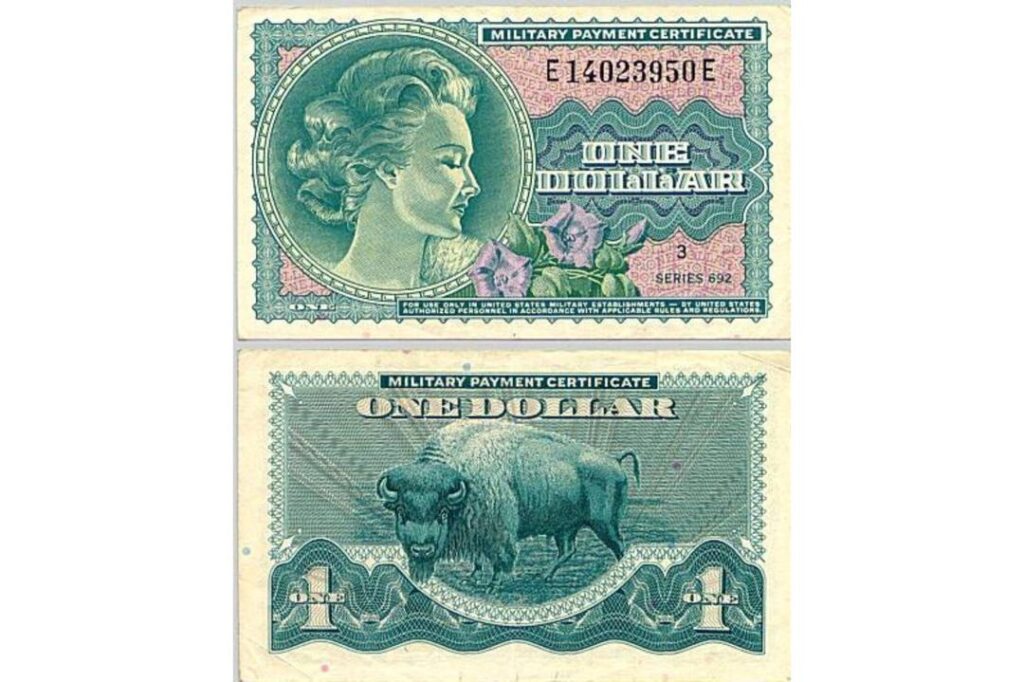

29. Military Payment Certificates

Military Payment Certificates, or MPCs, were a specialized type of currency used by U.S. soldiers serving overseas between 1946 and 1973. After World War II, the government realized that when American troops spent regular U.S. dollars in foreign countries like Japan, Germany, or Vietnam, it often caused problems with the local economy and fueled the “black market.” To prevent this, the military issued these colorful paper notes that could only be used by authorized military personnel in locations like base exchanges (PX) or clubs. They looked like play money but were a very serious tool for controlling the flow of cash in war zones and occupied territories.

The most interesting thing about MPCs was “C-Day” or Conversion Day. To stop local people from hoarding the notes, the military would suddenly announce a day where the old style of MPC was no longer valid. On that day, soldiers had to turn in all their old notes for a brand-new design. Anyone who wasn’t in the military was stuck with worthless paper. This system was used through the Korean War and the Vietnam War until it was finally discontinued in 1973 as the military moved toward using standard dollars and electronic systems. These certificates are now cherished by veterans as tangible reminders of their time serving in far-off lands during some of the 20th century’s biggest conflicts.

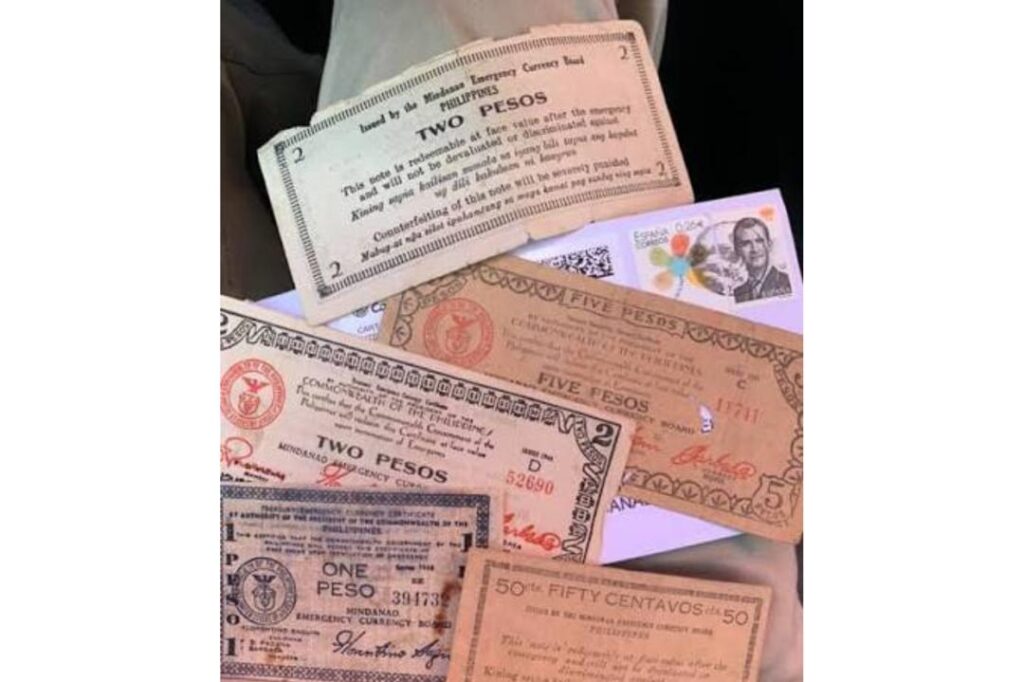

30. Emergency Currency Issues

Emergency currency refers to money created by local cities, banks, or even businesses during times of extreme national crisis when regular cash disappears. One of the most famous examples occurred during the “Panic of 1907” and again during the “Bank Holiday” of 1933 at the start of the Great Depression. When banks were forced to close their doors to prevent a total collapse, people suddenly had no way to get cash to buy food. In response, local clearinghouses and even some town governments printed their own “scrip”, temporary paper notes that local stores agreed to accept as if they were real U.S. dollars.

These notes were often very plain, sometimes even printed on wood or cardboard if paper was scarce. They were never meant to be permanent; the goal was simply to keep the local community from starving or going out of business until the federal government could fix the banking system. Once things stabilized, people would trade their “emergency scrip” back in for official currency, and the temporary notes were destroyed. These issues are a testament to the resilience of American communities. They show that even when the national financial system breaks down, people will find a way to trust one another and keep the wheels of daily life turning through cooperation and creativity.

Together, they remind us that money is never static, it evolves alongside the society that uses it.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.