1. Ring a Ring o’ Roses

Few nursery rhymes are as closely associated with grim history as Ring a Ring o’ Roses (Ring around the Rosie). One of the most widely accepted interpretations links the rhyme to outbreaks of the bubonic plague in England, particularly the Great Plague of 1665. The “roses” are often said to represent plague sores, while “posies” refer to herbs people carried to ward off illness. The final line, describing everyone falling down, mirrors the devastating mortality rates of the disease. While some historians debate how literal this interpretation is, the rhyme’s repeated association with mass illness and death has been documented in folklore studies and popular historical writing for decades, giving it a much darker legacy than its playful circle game suggests.

2. Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary

Mary, Mary, Quite Contrary is commonly believed to reference Queen Mary I of England, a ruler whose reign in the mid-16th century was marked by religious persecution. The “garden” in the rhyme is often interpreted as England itself, while the “silver bells” and “cockle shells” are thought to symbolize instruments of punishment or torture. The rhyme’s sharp tone may reflect opposition to Mary’s efforts to restore Catholicism, which led to the execution of hundreds of Protestants. Though interpretations vary, many historians agree the rhyme likely reflects political dissent rather than innocent gardening, making it a subtle but enduring critique embedded in children’s verse.

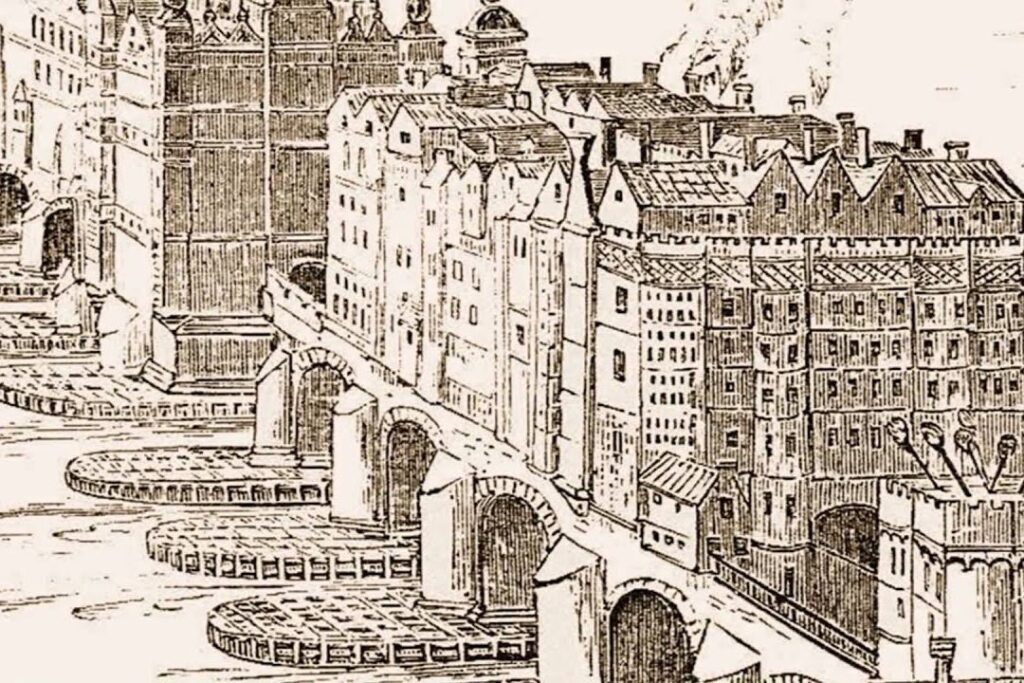

3. London Bridge Is Falling Down

London Bridge Is Falling Down is rooted in centuries of structural collapse, warfare, and folklore surrounding one of England’s most important landmarks. The bridge was repeatedly damaged by fires, attacks, and poor construction throughout medieval history. Some legends even suggest human sacrifice was believed to strengthen the bridge’s foundations, a theory frequently discussed in folklore research, though not proven by physical evidence. The many verses describing different materials failing reflect real attempts to rebuild the bridge over time. Rather than a simple song about construction, the rhyme captures a long history of instability, fear, and persistence tied to a vital crossing of the River Thames.

4. Rock-a-Bye Baby

Rock-a-Bye Baby stands out as an unusually unsettling lullaby, with imagery of a cradle falling from a tree. One historical explanation links the rhyme to political observation during the Glorious Revolution of 1688, with the “baby” symbolizing the future of the English monarchy. Another theory suggests it reflects Puritan views on child-rearing, warning against pride or instability. Regardless of interpretation, the song’s sudden, violent ending contrasts sharply with its soothing melody. This unsettling combination has long fascinated scholars and parents alike, reinforcing the idea that not all nursery rhymes were originally designed purely for comfort.

5. Jack and Jill

Jack and Jill is often interpreted as an allegory tied to political power struggles in 17th-century England. Some historians associate the characters with King Louis XVI of France and Marie Antoinette, whose downfall during the French Revolution shocked Europe. Others connect the rhyme to earlier English tax disputes involving King Charles I. The “fall” described in the verse may symbolize a loss of authority rather than a literal tumble. Though its origins remain debated, the rhyme’s enduring popularity has ensured these darker political interpretations remain part of its cultural legacy, far removed from its playful rhythm.

6. Humpty Dumpty

Humpty Dumpty is widely believed to be a riddle rather than a simple character, with one leading theory linking him to a cannon used during the English Civil War. According to this interpretation, the cannon was positioned on a wall and, once it fell, could not be repaired, echoing the rhyme’s famous lines. This explanation gained traction through historical analysis and military records discussed in popular history publications. The image of an egg-like figure came later through illustrations, softening the rhyme’s original meaning and obscuring its likely connection to warfare and technological limitations of the time.

7. Baa, Baa, Black Sheep

Baa, Baa, Black Sheep is often linked to medieval taxation policies, particularly the heavy wool taxes imposed during the reign of King Edward I. Wool was England’s most valuable export, and farmers were required to give significant portions of their profits to the Crown and the Church. The “three bags full” are commonly interpreted as these divisions. While modern versions are sung without context, historical discussions frequently highlight the rhyme as a subtle protest against economic exploitation. Its simplicity allowed it to be passed down orally without drawing attention from authorities, preserving its message through generations.

8. Three Blind Mice

Three Blind Mice is commonly associated with Queen Mary I and the persecution of Protestant officials during her reign. The “mice” are believed to represent three noblemen who opposed her religious policies and were executed. The farmer’s wife in the rhyme is often interpreted as the queen herself. This reading is supported by historical timelines and references in literary analyses, though, as with many nursery rhymes, absolute proof is elusive. Still, the rhyme’s violent imagery and historical parallels suggest it was never intended as harmless entertainment, but rather as a cautionary or political commentary.

9. Old Mother Hubbard

Old Mother Hubbard has been interpreted as a political satire aimed at Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, a powerful figure during the reign of King Henry VIII. In this reading, the empty cupboard represents the loss of wealth and influence following Wolsey’s fall from favor. The rhyme’s absurd sequence of events mirrors the instability and ridicule faced by disgraced political figures of the time. Literary historians have pointed out how humor was often used to disguise criticism, making rhymes like this both entertaining and subversive. Its survival reflects how coded storytelling could endure where direct commentary could not.

10. Sing a Song of Sixpence

Sing a Song of Sixpence contains imagery that many scholars link to the turbulent reign of Henry VIII. The “king in his counting house” is often seen as a reference to royal finances, while the “blackbirds baked in a pie” may symbolize nobles trapped by courtly politics. The rhyme reflects themes of wealth, control, and betrayal that defined Tudor England. While modern listeners hear only whimsy, historians note that such verses allowed people to comment on social inequality and political danger in a way that felt harmless. This layered meaning has helped the rhyme remain relevant for centuries.

11. This Little Piggy

This Little Piggy is often treated as a harmless finger-play rhyme, yet its structure reflects long-standing social and economic divisions. Folklore historians note that the verses mirror class distinctions in agrarian societies, where access to food and comfort was unevenly distributed. The pig who “went to market” and the one who “stayed home” suggest contrasting economic roles, while the pig with “none” reflects scarcity and hunger common among the poor. The final pig’s distress echoes the anxiety associated with poverty and uncertainty. While not tied to a single historical event, the rhyme captures everyday realities of survival in pre-industrial England, where food access defined social status and security far more than childhood songs let on.

12. Georgie Porgie

Georgie Porgie is frequently linked to George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, a powerful courtier during the reign of King James I. Known for scandal and favoritism, Villiers was widely criticized for his influence and personal behavior. The rhyme’s portrayal of a man who kisses girls and runs away reflects public resentment toward his reputation and perceived cowardice. Literary historians suggest the verse functioned as satirical commentary disguised as children’s entertainment. Its sing-song style allowed criticism of a prominent political figure to circulate safely among the public. Over time, the rhyme lost its political edge, becoming a playground chant while preserving echoes of early modern court intrigue.

13. Little Jack Horner

Little Jack Horner is often interpreted as a commentary on land seizures during the English Reformation. One theory connects the character to Thomas Horner, a steward who allegedly benefited from the dissolution of monasteries under King Henry VIII. The “plum” pulled from the pie is believed to symbolize property gained through political maneuvering rather than merit. Historians point out that the rhyme reflects widespread public awareness of corruption and opportunism during this period. Though details remain debated, the verse endures as a subtle reminder of how power and wealth were redistributed in turbulent times, hidden beneath a playful rhyme learned in childhood.

14. Here We Go Round the Mulberry Bush

This familiar rhyme has been linked to Wakefield Prison in 19th-century England, where inmates reportedly exercised around a mulberry tree. Folklore accounts suggest the song’s repetitive structure mirrors the monotonous routines of prison life. The verses describing daily tasks align closely with institutional schedules, reinforcing this interpretation. While not definitively proven, the association appears frequently in historical commentary and local tradition. The rhyme’s cheerful melody contrasts sharply with the restrictive environment it may describe, illustrating how grim realities were softened for oral tradition. Its endurance reflects how everyday hardship could be transformed into communal song.

15. Oranges and Lemons

Oranges and Lemons is deeply tied to the geography and social life of historic London. Each line references a church, with bells symbolizing different parishes and communities. The rhyme’s darker ending, involving debt and punishment, reflects the harsh consequences of financial failure in earlier centuries. Public debtors often faced imprisonment, and church bells were part of daily civic life, marking both celebration and judgment. Historians note that the rhyme preserves a sonic map of London while subtly acknowledging economic inequality. What begins as a cheerful tune ultimately hints at the serious social pressures that shaped urban life in the past.

16. Wee Willie Winkie

Wee Willie Winkie portrays a watchful figure enforcing bedtime, but its origins suggest broader themes of discipline and authority. Scholars have linked the rhyme to early efforts at regulating children’s behavior during a time when social order was strongly emphasized. The character’s patrol through streets and homes mirrors community surveillance common in tightly knit towns. While later softened into a gentle bedtime song, the rhyme reflects historical attitudes toward obedience and routine. Its imagery highlights how nursery rhymes often doubled as informal tools for social instruction, shaping behavior long before modern parenting guides existed.

17. There Was a Crooked Man

There Was a Crooked Man is frequently interpreted as political allegory rather than nonsense verse. One theory connects the rhyme to Scottish political unrest during the reign of King Charles I, with the “crooked” imagery reflecting perceived injustice and instability. The rhyme’s strange logic and unresolved ending mirror the confusion of shifting allegiances and contested authority. Literary historians suggest such ambiguity allowed the verse to circulate without clear attribution or punishment. Over time, its political undertones faded, leaving behind a surreal rhyme that still carries traces of historical tension beneath its playful surface.

18. Ladybird Ladybird

Ladybird Ladybird has roots in agricultural life, where farmers burned fields to clear land, often destroying insects’ habitats. The rhyme’s plea for the ladybird to flee reflects genuine concern for both crops and creatures during controlled burns. Folklore studies highlight how the verse captures a moment of environmental awareness long before modern conservation movements. Its emotional tone suggests empathy shaped by lived experience rather than abstract sentiment. Though now sung lightly, the rhyme preserves a record of rural practices and the unintended consequences they carried for small, vulnerable forms of life.

19. Hush Little Baby

Hush Little Baby differs from many nursery rhymes by promising material rewards instead of moral lessons. Cultural historians note that its structure reflects early American consumer values, where comfort and reassurance were tied to possessions. The repeated failure of each promise introduces subtle anxiety, suggesting instability beneath parental reassurance. While not linked to a single historical event, the lullaby reflects social conditions where uncertainty was common, and hope was offered through tangible goods. Its enduring popularity lies in this blend of comfort and unease, revealing how even soothing songs can echo deeper cultural realities.

Revisiting them with context reminds us that storytelling has always been a way to process the world, even when the audience is very young.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.