1. Camels Have Built-In “Sand Goggles” and Triple Eyelids

Camels are brilliantly adapted for desert life, and their eyes are no exception. Each camel has three eyelids and two rows of long lashes that shield its eyes from whipping sand and the harsh sun. One of those eyelids is a translucent membrane that functions like a natural pair of goggles, allowing camels to see even during sandstorms. This adaptation helps them keep moving through blinding conditions without damaging their vision.

Camels also have slit-like nostrils that they can seal shut, thick lips that let them chew thorny desert plants, and broad, padded feet that prevent them from sinking into the sand. Every inch of their anatomy is built for extremes, blistering heat, shifting dunes, and long treks without water. Their eyes are especially remarkable, allowing them to navigate when visibility for most animals would drop to zero. San Diego Zoo

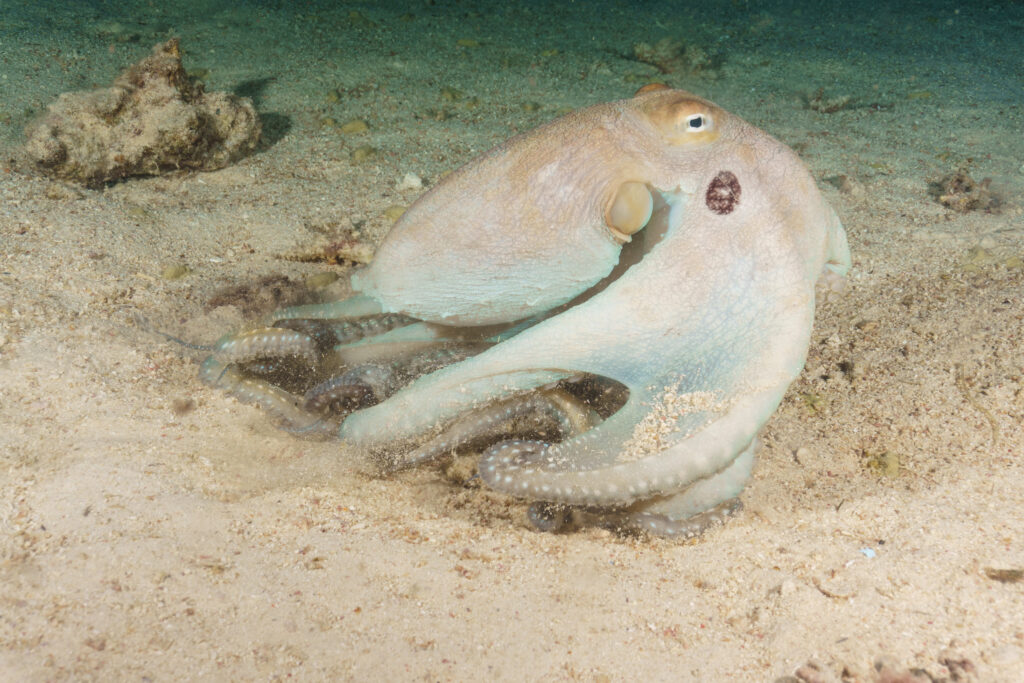

2. Octopuses Have Three Hearts, And One Stops Every Time They Swim

Octopuses aren’t just the stealthiest shapeshifters in the sea; they have three hearts, and one stops every time they swim. Two hearts pump blood to their gills, while a third sends oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body. But that third heart shuts off when they jet through the water, which is part of the reason they prefer crawling across the ocean floor. Their copper-based blood, which appears blue, is called hemocyanin, and it’s much better than hemoglobin at holding oxygen in cold, low-oxygen environments.

They’re also covered in neurons, over 500 million, with more than half spread through their arms. Each arm can taste, touch, and even make independent decisions. Combine that with the ability to camouflage instantly and solve puzzles better than some lab mammals, and you’ve got a creature so strange, some researchers call them “aliens of the deep.” Smithsonian Ocean Portal.

3. Elephants Think Humans Are Cute (Like We’re the Puppies to Them)

We adore elephants, but the feeling may be mutual. Behavioral researchers have found that elephants display curiosity and affection when seeing humans, especially smaller ones. They’ve been observed flapping their ears, rumbling softly, and extending their trunks to investigate us, behaviors they usually reserve for their own young. Some ethologists suggest elephants perceive us as we perceive puppies: small, non-threatening, and oddly fascinating.

Their emotional intelligence runs deep. Elephants mourn their dead, recognize themselves in mirrors, and communicate with low-frequency rumbles that travel over six miles. They form lifelong matriarchal bonds and show empathy, memory, and cooperation that rival great apes. One matriarch even recognized a zookeeper’s voice after two decades apart. National Geographic

4. Crows Can Hold Grudges—and Teach Their Friends to Hate You

Crows are incredibly intelligent and socially savvy. Researchers wearing realistic masks captured and tagged wild crows in a long-term study at the University of Washington. Years later, those same masked researchers were still being dive-bombed and scolded by the birds, who had not only remembered the face but also passed the warning on to others. Even crows who hadn’t witnessed the original event learned to recognize the “dangerous” mask, proving they share information across generations.

Crows also remember kindness. They’ve been known to leave small gifts like earrings, shiny pebbles, or bits of wire for humans who feed them regularly. They can recognize over 30 individual faces, use tools, and solve puzzles with steps and planning. In terms of memory, cooperation, and emotional range, their brains function similarly to primates. University of Washington

5. Sloths Can Hold Their Breath Longer Than Dolphins

Sloths may look like the laziest animals in the forest, but their slow pace hides some surprising abilities. For one, they can hold their breath underwater for up to 40 minutes, far outlasting dolphins, who average around 10. Sloths achieve this by slowing their heart rate by nearly 90 percent when submerged, conserving oxygen and avoiding detection from predators. Though they aren’t aquatic animals, they are surprisingly good swimmers and often use water to travel more efficiently through their rainforest habitats.

Their metabolism is one of the slowest in the animal kingdom, and digestion can take over a month to complete. Sloths have extra neck vertebrae that enable them to rotate their heads 270 degrees, allowing them to scan for threats without moving their bodies. These adaptations aren’t about laziness, but rather about survival in a world where energy conservation keeps them alive. BBC Earth

6. Tardigrades Can Survive in Space, Boiling Acid, and Freezing Vacuum

Tardigrades, also called water bears, are microscopic creatures that survive almost anything. They’ve withstood temperatures near absolute zero, boiling water, crushing pressure at the bottom of the ocean, and even exposure to the vacuum of space. When conditions get extreme, they curl into a dried-up ball called a tun, shutting down their metabolism and suspending life for years, possibly even decades. Once rehydrated, they come back to life like nothing happened.

Their secret lies in a unique protein that protects their DNA from radiation and environmental damage. They’ve survived being blasted into space on satellites and experiments outside the International Space Station. Some were revived after being frozen for more than 30 years. Tardigrades may not look like much, but they’re among Earth’s toughest life forms, and scientists are studying them for clues to preserving human tissue and space travel resilience. Scientific American

7. Giraffes Have the Same Number of Neck Bones as You Do

Despite their towering necks that can stretch over six feet long, giraffes have just seven neck vertebrae, the same number found in humans, mice, and nearly all mammals. The difference is in the size of each bone. A single giraffe vertebra weighs several pounds and can be over ten inches long. These elongated bones, strong ligaments, and powerful muscles allow giraffes to hold their heads high while browsing treetops or surveying for predators.

Giraffes also use their necks in combat. Males use “necking,” swinging their heads like battering rams to establish dominance and win access to mates. These fights can last hours, with blows powerful enough to knock a rival off balance. Their neck structure and a specially adapted cardiovascular system, which manage blood flow to their brains, make giraffes some of the most uniquely engineered mammals alive. American Museum of Natural History

8. Blue Whales Have Hearts the Size of Golf Carts

The blue whale is the largest animal ever to have lived, dwarfing even the most enormous dinosaurs. Its heart alone can weigh more than 400 pounds and is roughly the size of a golf cart. Each beat is so powerful that it can be heard from two miles away through underwater microphones. The aorta, the artery that carries blood from the heart, is large enough for a human child to crawl through. Despite their enormous size, blue whales feed primarily on tiny krill, consuming up to four tons daily.

These giants communicate with deep, rumbling calls that are among the loudest sounds produced by any animal. They are capable of traveling across entire ocean basins. They were nearly driven to extinction during the commercial whaling era, but international protections have helped some populations begin to recover. Everything about the blue whale is record-breaking, including the size of its tongue, which can weigh as much as an elephant. Natural History Museum

9. Sea Otters Hold Hands While Sleeping So They Don’t Drift Apart

Sea otters are famous for their adorable habit of holding hands while napping; it’s not just for show. When floating in groups called rafts, sea otters grip each other’s paws or entangle themselves in kelp to avoid drifting apart in ocean currents. This behavior is significant for mother-pup pairs, who rely on constant physical contact to stay close and prevent separation in the sea’s ever-shifting surface.

Otters also wrap their pups in kelp to secure them while diving for food, swaddling them in seaweed babysitters. But beneath the cuteness lies serious ecological muscle. Otters are a keystone species because they help control sea urchin populations, protecting the kelp forests that support entire marine ecosystems. Their role in the food chain, tool use, and social bonding has made them a focal point in marine conservation. Monterey Bay Aquarium

10. Frogs Can Freeze Solid and Thaw Back to Life

Some frogs, like the wood frog found in Alaska and Canada, have developed a truly astonishing adaptation: they can freeze completely solid during winter and return to life in spring. During this frozen state, their hearts stop beating, breathing halts, and up to 70 percent of their body water turns to ice. To survive, they flood their cells with glucose, which acts like antifreeze, preventing their tissues from bursting or being damaged during the deep freeze.

During this suspended state, the frog appears completely lifeless. But once temperatures rise, it thaws out, its heart restarts, and within hours, it hops away as if nothing had happened. Scientists study these frogs to gain a better understanding of cryopreservation and how cells survive extreme cold. The lessons learned from frozen frogs could one day improve human organ storage and transplant technology. National Park Service

11. Male Seahorses Get Pregnant and Give Birth

In the seahorse world, the males experience pregnancy and do it with incredible precision. After an elaborate courtship dance, the female deposits eggs into a special brood pouch on the male’s abdomen. He fertilizes the eggs and nurtures them for weeks, controlling the internal environment by adjusting salinity and temperature. When the babies are ready, the male goes into full labor and gives birth to dozens, or sometimes hundreds, of tiny, fully formed seahorses.

This reversal of reproductive roles is nearly unique in the animal kingdom and has fascinated biologists for decades. The male’s pouch functions similarly to a placenta, supplying nutrients and oxygen while removing waste. After birth, the young seahorses are entirely independent. Researchers study this rare biological setup to better understand evolutionary adaptations in reproduction and parental care. Australian Museum

12. Dolphins Call Each Other by Name

Dolphins are among the few animals that use vocal labels similar to names. Each dolphin develops a unique signature whistle early in life, which serves as its personal identifier. Other dolphins use these whistles to call to specific individuals, even when they are out of sight. These “names” remain consistent for decades, and dolphins can recognize a friend’s or family member’s whistle even after 20 years apart.

Even more remarkable is that dolphins sometimes mimic the names of close companions, especially during reunions or cooperative behaviors. This form of vocal learning shows that dolphins don’t just communicate; they engage in socially complex relationships that require memory, identity recognition, and intention. Their name-based calls are among non-human species’ most substantial evidence of symbolic communication. NPR

13. Platypuses Glow Under UV Light

The platypus is already one of evolution’s most unexpected creations, with its duck bill, webbed feet, venomous spur, and egg-laying habits. But scientists recently discovered one more twist: the platypus glows under ultraviolet light. Under UV exposure, their fur fluoresces with a bluish-green glow, a trait first spotted in preserved specimens and later confirmed in wild and live animals.

This type of biofluorescence is rare in mammals and may serve several purposes, including camouflage under moonlight, interspecies communication, or even as a leftover evolutionary trait. Other animals known to fluoresce include certain birds, reptiles, and sea creatures, but the platypus now joins that strange club. Researchers continue to investigate whether this glow gives the platypus an advantage or is a mysterious quirk of its biology. BBC Earth

14. Some Sharks Are Older Than the United States

The Greenland shark holds the record for the longest-living vertebrate on Earth. Radiocarbon dating of eye tissue revealed that some individuals are over 400 years old, meaning they were alive when Shakespeare was writing plays and may have swum the icy North Atlantic during the American Revolution. These deep-sea dwellers grow extremely slowly, about half an inch per year, and don’t reach sexual maturity until they’re around 150 years old.

They thrive in frigid, dark waters where their sluggish metabolism and lack of natural predators contribute to their longevity. Greenland sharks can grow up to 24 feet long and have been found with odd items in their stomachs, including polar bear remains. Their slow aging process is now being studied for clues on how to extend human lifespan and combat age-related diseases. Science

15. Parrots Name Their Chicks—Using Unique Call

Parrots aren’t just expert mimics; they can also invent original vocalizations. In species like the green-rumped parrotlet, researchers have found that parents assign their chicks unique signature calls, essentially names. These individualized sounds help parrots recognize one another in large, noisy flocks and maintain strong family bonds over time. The chicks adopt these calls early and continue using them into adulthood, a form of vocal learning that’s incredibly rare in the animal kingdom.

Even more fascinating is that other parrots respond to these names and even repeat them to address individuals directly. This complex communication system demonstrates that parrots utilize sound socially and symbolically, not just to mimic, but also to identify and connect. The discovery underscores the bird’s advanced cognitive abilities, which rival those of dolphins and great apes. Royal Society

16. Ants Can Build Living Bridges and Rafts

When faced with floods, gaps, or tricky terrain, ants don’t retreat; they engineer. Army and fire ants can link their bodies to create structures like bridges, ladders, and rafts. These formations are made by hundreds or thousands of ants gripping each other with legs and mandibles, forming a flexible and dynamic structure. The group constantly adjusts to balance weight and respond to movement, acting like a living construction crew with no central leader.

During floods, fire ants can create watertight rafts that float for weeks, swapping positions so no single ant stays submerged too long. This is all powered by “swarm intelligence,” where simple individual rules produce complex group behavior. The ants aren’t following orders; they’re using decentralized cooperation to solve real-time physical challenges. These collective survival strategies have even inspired advances in robotics and traffic design. Georgia Tech

17. A Group of Flamingos Is Called a “Flamboyance”

Flamingos aren’t just graceful, they’re dramatic. So it’s fitting that a group of them is called a flamboyance. The name matches their synchronized dances, head-flagging rituals, and over-the-top pink feathers. These social birds gather in flocks of hundreds to thousands and use elaborate displays to attract mates, often performing in unison like a feathered chorus line. The more coordinated the group, the more attractive the individuals appear to potential partners.

Their iconic pink color comes from carotenoids in the shrimp and algae they eat; flamingos fade to a pale gray without the proper diet. They’re also specially adapted to feed upside down, filtering muddy water through comb-like structures in their beaks. Beyond the flash, flamingos are hardy; they breed in volcanic lakes, salt flats, and highly alkaline waters where few other animals survive. Their flamboyant name is just the surface of a truly wild bird. Merriam-Webster

18. Bees Can Recognize Human Faces

Despite having brains the size of a sesame seed, bees can recognize individual human faces. In lab experiments, honeybees were trained to associate specific human faces with a sugary reward. Later, when presented with photos, they accurately identified the same faces, even after short delays. Bees don’t just memorize facial parts; they use “configural processing,” the same strategy humans rely on to recognize faces.

This remarkable visual skill is crucial in the wild, where bees must identify flowers, landmarks, and hive mates. It also suggests that intelligence isn’t always about brain size; it’s about processing efficiency. Engineers studying bee vision are using it to design better facial recognition software. Bees’ ability to learn and generalize patterns demonstrates cognition once thought impossible in insects. Scientific American

19. Koalas Have Fingerprints Almost Identical to Humans

Koalas have fingerprints so similar to ours that they can be mistaken for human prints at a crime scene. Their fingers feature whorls, ridges, and loops nearly indistinguishable from human ones—even under a microscope. This evolutionary quirk is thought to help them grip eucalyptus branches and manipulate leaves for feeding. What’s especially unusual is that koalas are the only known marsupials to have developed this trait.

Scientists believe that koala fingerprints evolved independently through convergent evolution, a process in which unrelated species develop similar features. Even their closest relatives, like wombats, don’t share this trait. Koala fingerprints form late in fetal development and remain unchanged, just like humans. It’s a reminder that evolution sometimes retraces its steps, even across entirely different branches of the tree of life. Live Science

20. Mantis Shrimp Punch So Fast They Boil Water

The mantis shrimp isn’t just a colorful crustacean; it’s a high-speed brawler. Using spring-loaded appendages, the mantis shrimp delivers punches at over 50 miles per hour, accelerating faster than a .22 caliber bullet. The strike is so rapid that it causes cavitation bubbles in the water. When these bubbles collapse, they create a strong secondary shockwave to stun prey and momentarily boil the surrounding water.

Their punch is powerful enough to crack aquarium glass and shatter crab shells. Beyond brute force, mantis shrimp also possess some of the most sophisticated eyes in the animal kingdom. They can detect polarized light and see 12 to 16 types of color receptors (humans only have three), granting them a vision of the world far beyond our own. These visual and mechanical feats make them one of evolution’s most unique success stories. PBS

21. Bats Give Each Other Personalized Calls, Just Like Names

Egyptian fruit bats have been recorded using individualized vocalizations directed at specific colony members, essentially calling each other by name. Researchers found that bats argue, flirt, and maintain social hierarchies using context-specific calls personalized for individual recipients. They even change their tone based on who they’re addressing, similar to how humans adjust their speech when talking to different people.

These calls are not simple squeaks; they carry identity, emotion, and social context information. Bats also learn dialects and adjust their vocalizations depending on their social group, showing remarkable flexibility. This level of vocal complexity puts them in league with dolphins, parrots, and primates regarding communication. Their bat “gossip” was documented in acoustic studies by researchers at Tel Aviv University. Smithsonian Institution.

22. Penguins Propose With Pebbles

Courtship begins with a rock in several penguin species, including Adélie and gentoo penguins. During breeding season, male penguins search for the smoothest, most perfect pebble to present to a potential mate. If the female accepts the gift, she adds it to her nest, and the pair begins building a stone mound together. These nests help protect eggs from flooding and cold ground, so the pebble isn’t just romantic but practical.

Competition can be fierce, with males stealing pebbles from rival nests and guarding their best stones. Because many penguins are monogamous and return to the same mate and nesting grounds year after year, this small token can kick off a lifelong bond. Scientists have documented pebble courtship behaviors across multiple Antarctic colonies. BBC

23. Butterflies Taste With Their Feet

When a butterfly lands on a leaf, it’s not just resting, it’s doing a taste test. Butterflies have taste receptors on their feet (specifically on their tarsi), allowing them to sample chemical cues from plants before deciding to feed or lay eggs. These sensors detect sugars, salts, and even toxins, which is crucial for females selecting the perfect host plant for their future caterpillars.

Some butterflies are so specialized that they only lay eggs on one plant species, and being able to instantly “taste” that plant upon landing saves valuable time and energy. Monarchs, for example, exclusively choose milkweed, which contains toxins that protect their offspring from predators. The taste-through-feet adaptation highlights how evolution repurposes body parts for surprising functions. Smithsonian Institution

24. Lizards Can Breathe Through Their Skin—Sort Of

While most reptiles rely strictly on lungs, some lizards like the green anole have developed a clever adaptation: limited skin-based respiration. They can absorb small amounts of oxygen through moist, thin-skinned areas around their mouth and cloaca, helping them survive brief submersions or oxygen-poor environments. Though not as efficient as amphibian skin breathing, it gives them a survival edge in tight situations.

Some anoles take it further with a scuba trick. They trap air bubbles around their snouts underwater and “rebreathe” them, extending dive times up to 15 minutes. This natural diving bell lets them forage longer or hide from predators. It’s a remarkable example of biological ingenuity from an animal that is often overlooked. Mongabay

25. Cows Have Best Friends—and Get Stressed When Separated

Cows form close friendships and show signs of emotional distress when separated from their preferred companions. In studies, cows paired with their best friend had lower heart rates and cortisol levels, indicators of reduced stress. When separated, they showed signs of anxiety, like increased vocalization, pacing, and decreased food intake.

These social bonds suggest that cows experience complex emotions and benefit from consistent companionship, similar to that of dogs or elephants. It also raises ethical considerations for farming practices that disrupt these relationships. The more we learn about livestock cognition, the more we see emotional depth where we least expect it. University of Northampton

26. Tarantulas Keep Tiny Frogs as Pest Control Roommates

In parts of South America and India, large tarantulas have been found cohabiting with tiny frogs, an unlikely alliance that benefits both. The tarantula provides shelter in its burrow, while the frog eats ants and insects that might threaten the spider’s eggs. Remarkably, the tarantula doesn’t eat the frog, and may even recognize particular frog species as allies rather than prey.

This mutualistic relationship has evolved independently in several regions, and researchers believe the spiders may identify “friendly” frog species through chemical cues. Sometimes, the spiders even appear to protect their froggy roommates from predators. It’s a real-world example of symbiosis that challenges assumptions about how predators interact with much smaller animals. Biology Letters

27. Wombat Poop Is Cube-Shaped

Wombats are known for producing poop that comes out in neat little cubes, and yes, it’s real science, not internet legend. Researchers discovered that the unique shape results from how the wombat’s intestines contract: slowly and unevenly along their stretchy walls, molding the feces into blocks. This helps the poop stay put on rocks or logs, which is essential since wombats use it to mark territory.

The flat-sided design prevents the pellets from rolling away, making their messages more stable and noticeable. Scientists even recreated the effect in the lab using balloon-like models of the wombat intestine. It’s the only known case of cuboid poop in the animal kingdom, and a surprisingly efficient adaptation. Science.org

28. Snakes Can Still Bite Minutes After Losing Their Heads

Even after decapitation, a snake’s severed head can still deliver a deadly bite. This isn’t a horror myth—it’s a real consequence of how reptile nervous systems work. Without the brain to regulate it, the head can still respond reflexively to stimuli for up to an hour. If something brushes against the mouth, it might trigger a final strike, complete with venom injection.

This has been documented in species like rattlesnakes and cobras, leading experts to warn that even “dead” snakes should be cautiously handled. It’s a freaky example of how simple neural circuits can remain active without conscious thought. The reflex has caused numerous bites in people trying to dispose of or photograph decapitated snakes. BBC

29. Axolotls Can Regrow Their Brain, Spine, and Heart

Axolotls, those wide-eyed amphibians from Mexico, aren’t just cute, they’re regenerative powerhouses. These animals can regrow entire limbs, spinal cords, parts of their heart, and even chunks of their brain. Their cells revert to a stem-cell-like state at the injury site, then rebuild the structure, nerves, bone, tissue, and all, with incredible precision and without scarring.

In lab studies, axolotls have been shown to restore severed spines within three weeks and regrow functioning brain tissue. This regenerative ability has made them a focus of medical research, especially for understanding how we might one day heal spinal injuries or regrow organs. Their secrets could revolutionize human medicine. Nature

30. Orcas Pass Down Traditions Just Like Human Families

Orcas, also known as killer whales, live in tightly knit pods with cultural traditions passed from generation to generation. Some pods specialize in hunting fish, while others target seals or stingrays, each with distinct techniques, vocal dialects, and dietary preferences. These behaviors are learned, not instinctive, and are taught by older members to the young, much like human customs.

Remarkably, post-menopausal female orcas, often referred to as grandmothers, play a critical role in guiding pods and improving survival rates. Their leadership aids in food finding and maintaining pod cohesion. Scientists compare these cultural distinctions to those found in human societies, noting that orcas are among the few species known to pass down complex behaviors socially, rather than genetically. Royal Society

31. Froghoppers Can Jump Higher Than Any Known Animal

Froghoppers, also called spittlebugs, may be tiny, barely a quarter-inch long, but they hold the highest jump relative to body size. These insects can leap over 28 inches vertically, which is more than 100 times their body length, outclassing fleas and even tree frogs. They accomplish this feat using a hydraulic-like mechanism in their legs, storing energy in a protein called resilin.

When they jump, that energy is released in milliseconds, launching them at speeds over 13 feet per second and generating more G-force than a space shuttle launch. This insane jumping efficiency has inspired scientists to design spring-loaded micro-robots. Froghoppers prove that the smallest animals can break the biggest records. BBC

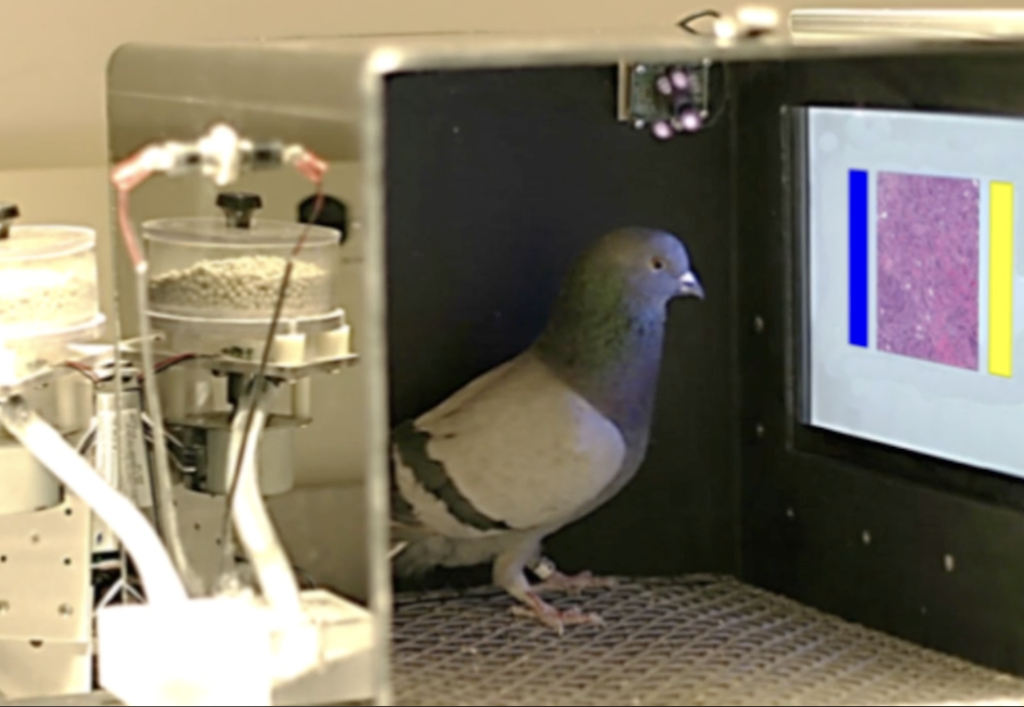

32. Pigeons Can Be Trained to Detect Cancer and Read Words

Pigeons might seem like urban background noise, but they’re astonishingly bright. In one study, pigeons trained with food rewards could distinguish between cancerous and healthy breast tissue slides with up to 85% accuracy. When working in groups, their diagnostic success rate improved even more, a phenomenon dubbed the “flock effect.”

Even more surprisingly, pigeons have been trained to recognize up to 60 English words, identifying them from gibberish using pattern recognition. Their visual processing skills rival those of primates in certain tests, and their talents have been applied to a range of fields, from military messaging to art analysis. PLOS ONE

33. Starfish Can See—With Eyes on the Tips of Their Arms

Starfish may not have a face, but they have eyes, one at the tip of each arm. These eyespots can detect light and shadow, helping the starfish orient itself and move toward or away from its environment. While they don’t produce detailed images, the vision is good enough to help starfish find coral reefs or avoid predators.

In lab studies, starfish with intact eyes consistently navigated toward coral, while those with damaged eyes wandered. The number of eyes depends on the starfish’s number of arms, with some species sporting dozens of simple visual sensors. It’s a quiet kind of vision that still packs a directional punch. Oxford Academic

34. Octopuses Can Edit Their Own Genetic Instructions in Real Time

Octopuses have a strange genetic trick that has made scientists rethink how evolution works. Unlike most animals that rely on slow DNA mutations passed through generations, octopuses can edit their RNA on the fly, tweaking how genes are read in real time. Think of RNA like a recipe you follow to cook dinner; octopuses can change the recipe while cooking to adjust to their environment, especially in their brains and nervous systems.

This means they can fine-tune proteins on demand, helping them adapt to temperature changes, navigate new habitats, or adjust their cognitive responses. Some researchers believe this is part of why octopuses are so intelligent: they’ve essentially evolved an alternate path to brain complexity. The phenomenon is so radical that a study published in Cell suggested it may have slowed traditional genetic evolution in favor of extreme flexibility. Cell Press

35. Crows Understand Water Displacement—Like a Child Genius

Crows don’t just use tools; they understand fundamental physics. In a famous series of experiments inspired by Aesop’s fable “The Crow and the Pitcher,” researchers gave crows a tube partially filled with water and a floating treat just out of reach. The birds figured out how to raise the water level by dropping stones, bringing the reward within reach. They chose solid objects over hollow ones and avoided items that would float, showing a working grasp of volume displacement.

This puts crows on par with 5- to 7-year-old children in terms of problem-solving ability. These feathered physicists can also plan steps ahead, use tools, and adapt strategies on the fly. Their advanced cognition challenges the notion that large brains are the sole path to intelligence. PLOS ONE

36. Turtles Can Breathe Through Their Butts

As odd as it sounds, some turtles are capable of cloacal respiration, which means they can absorb oxygen through their rear ends. More specifically, they use their cloaca, a multi-purpose opening for excretion and reproduction, lined with blood vessel-rich sacs allowing gas exchange. This quirky adaptation allows particular species, like the Australian Fitzroy River and the North American painted turtle, to stay submerged without using their lungs.

This method is convenient during winter hibernation under ice, when surfacing for air isn’t an option. These turtles can slow their metabolism dramatically and switch to breathing through their cloaca to survive in cold, oxygen-poor water. It’s a brilliant biological workaround that helps them outlast predators and harsh seasonal changes. Scientists have studied this behind-the-scenes breathing trick extensively. Live Science

37. Dogs Can Smell Your Feelings—Literally

Dogs don’t just sense your mood; they smell it. Research has shown that dogs can detect human emotional states like fear, happiness, and stress through changes in scent. When we’re afraid or anxious, our bodies release chemical signals, like increased cortisol and adrenaline, that dogs can detect through their robust olfactory systems. They process these cues to determine whether we’re relaxed, alert, or even in danger.

In one study, dogs exposed to sweat samples from stressed people showed signs of anxiety themselves, including a faster heart rate and increased cortisol levels. They also sought comfort from their owners, exhibiting behavior similar to that of empathy. With over 300 million scent receptors in their noses, dogs are walking emotional detectors, tuned into the subtleties of human chemistry. NPR.

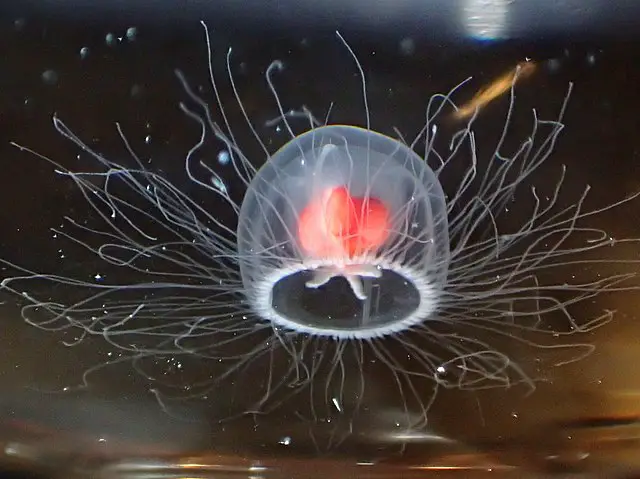

38. Jellyfish Can Live Forever (Sort Of)

The jellyfish Turritopsis dohrnii has a biological escape hatch from death. When faced with injury, starvation, or environmental stress, this tiny, translucent creature reverts its adult cells into an earlier life stage, transforming into a juvenile polyp. From there, it grows into an adult, starting its life cycle anew. This process, called transdifferentiation, allows it to potentially repeat this cycle endlessly, earning it the nickname “the immortal jellyfish.”

While individual jellyfish can still die from disease or predation, the species’ cellular ability to bypass death has fascinated scientists. Understanding how Turritopsis reprograms its cells could inform research on aging, cancer, and regenerative medicine. It’s not exactly eternal life, but it’s one of the closest biological approximations nature has produced. PNAS

39. Horses Can Communicate Using Symbols to Express Preferences

Horses aren’t just emotionally intelligent; they can also learn to communicate using visual symbols. In a study conducted in Norway, horses were trained to use boards with different markings to signal whether they wanted a blanket put on, taken off, or left alone. After just a few days of training, the horses consistently approached the correct symbol based on the weather, demonstrating that they understood both the symbols and the concept of choice.

The horses didn’t just memorize actions; they adjusted their responses based on changing conditions, like cold or sun. This shows symbolic understanding and the ability to make decisions and express comfort levels. It’s a rare and remarkable level of self-awareness and learned communication in a domesticated animal. American Psychological Association

40. Cuttlefish Can Pass the Marshmallow Test

The famous marshmallow test evaluates a child’s ability to delay gratification for a bigger reward. Surprisingly, cuttlefish—those squishy, color-changing cephalopods can do it too. In experiments, they learned to wait for a tastier snack instead of immediately grabbing a lesser one. The longer they waited, the better the treat they received.

This self-control is linked to intelligence, suggesting that cuttlefish may rival some vertebrates in cognitive complexity. Researchers believe this skill evolved to help them hunt strategically in complex environments. It’s a shocking level of restraint from an animal without a backbone. Live Science

41. Snow Monkeys Bathe in Hot Springs to Beat the Cold

Japanese macaques, also called snow monkeys, have figured out how to stay warm in winter. In the snowy mountains of Nagano, they soak in natural hot springs, sometimes lounging for hours in groups. This behavior wasn’t instinctual; it started with a few clever individuals and spread socially, like a cultural tradition.

Scientists observed that lower-ranking monkeys often wait their turn while alphas claim the best soaking spots. The habit reduces stress and conserves energy during harsh winters, showing adaptability, social intelligence, and learning. It’s one of the clearest examples of non-human animals exhibiting a comfort behavior that mirrors our own. PBS

42. Some Fish Can Change Their Sex—More Than Once

In the underwater world, identity can be surprisingly fluid, literally. Several fish species, like the clownfish and the wrasse, can change sex during their lifetime. Clownfish are born male, but when the dominant female dies, the top-ranking male transforms into a female to keep the breeding cycle going. Wrasses, on the other hand, often start life as females and switch to male when it’s time to take over a harem. These changes aren’t just behavioral, they’re full biological transitions, involving hormone shifts and organ remodeling.

Even more astonishing, some species can switch back and forth depending on the social situation. This remarkable flexibility enables fish to adapt their reproductive roles in response to group dynamics and population needs. It’s an evolutionary strategy that ensures survival, efficiency, and a steady supply of mates. These transformations have long fascinated marine biologists. Ecology Letters

43. Elephants Can Detect Rainstorms 150 Miles Away

Elephants may be massive, but they’re also finely tuned weather detectors. Using infrasound, vibrations below the range of human hearing, elephants can pick up the rumble of distant thunder and the movement of rainstorms from over 150 miles away. These deep, low-frequency sounds travel through the ground and air, allowing elephants to sense weather changes and even migrate toward water sources long before the rain arrives.

This sensory superpower enables elephants to survive in drought-prone landscapes and may also play a role in long-distance communication between herds. Researchers have even proposed that elephants can “discuss” approaching weather with one another. It’s another reason these giants are among nature’s most perceptive travelers. Science Daily

44. Crocodiles Cry Real Tears—But Not for the Reason You Think

The term “crocodile tears” has been used for centuries to describe fake sorrow, but these are biologically real. When crocodiles eat, especially during intense feeding, their tear glands are stimulated, likely due to pressure on the jaw and surrounding sinuses. The tears help keep their eyes moist and flush out irritants, not express emotion.

This phenomenon has led to centuries of myth-making, but now scientists have discovered the real cause. In a study where crocodiles were filmed eating partially on land, visible tear production occurred during feeding in five of seven individuals. While the timing may seem emotional, it’s simply a side effect of biology. Still, it’s oddly poetic that one of nature’s fiercest predators weeps while it devours prey. Science Daily

45. Naked Mole Rats Feel No Pain from Acid or Spice

Naked mole rats may look like squirmy little sausages, but they are biomedical marvels. These rodents are immune to pain caused by acid or capsaicin, the compound that makes chili peppers hot. That’s because their nerves lack a key neurotransmitter that mammals typically use to detect burning sensations. Researchers believe this adaptation evolved to help them survive in their underground tunnels, which are low in oxygen and high in carbon dioxide, resulting in acidic conditions.

Even more bizarre, naked mole rats can survive without oxygen for up to 18 minutes by switching to a plant-like metabolism, utilizing fructose instead of glucose as their primary energy source. This makes them prime candidates for medical research into pain relief, strokes, and hypoxia tolerance. Their pain-proof biology was reported in Science News

46. Garden Eels Live Half-Buried and Rarely Let Go

Garden eels are the introverts of the reef world. These slender, snake-like fish spend nearly their entire lives buried in the sand, with just their heads sticking out like blades of grass. Colonies can include hundreds of eels swaying with the current, each anchored to its burrow. They vanish like periscopes retracting if threatened, sometimes not reemerging for hours.

What’s wild is how rarely they leave home. Each eel commits to one burrow for life, using a slimy secretion to reinforce the walls. They feed on plankton drifting by and communicate through subtle body movements. Watching a garden eel colony at work is like seeing a living underwater meadow. Their burrow-bound lifestyles were detailed in a feature from Smithsonian Magazine

47. Hippos Produce Their Own Natural Sunscreen

Despite their rugged appearance, hippos have incredibly sensitive skin prone to sunburn and dehydration. To protect themselves, they secrete a thick, reddish-orange fluid called “blood sweat.” It’s not blood or sweat, but a natural cocktail of acids that serves as sunscreen and an antibiotic. This secretion absorbs ultraviolet rays and moistens their skin under the scorching African sun.

The fluid contains two main compounds: one that absorbs ultraviolet light and another that prevents bacterial growth on wounds. These secretions are chemically unique and have even sparked interest from scientists developing new types of bio-safe sunscreen. Nature engineered an elegant, low-maintenance solution for an animal that spends most of its life exposed to the elements. Nature

48. Saiga Antelopes Have Built-In Air Filters on Their Faces

Thanks to its oversized, bulbous nose, the saiga antelope appears to have wandered in from another planet. However, that distinctive nose is ideally suited to life on the Central Asian steppes. The downward-facing nostrils act like built-in air filters, warming cold air in winter and filtering out dust during summer migrations. This allows the saiga to breathe efficiently while sprinting across vast, arid terrain.

They’re also ancient survivors, having roamed alongside mammoths and saber-toothed cats. Sadly, they’re now critically endangered due to habitat loss and disease outbreaks. Their nose, once a comical curiosity, has become a symbol of resilience and conservation urgency. World Wildlife Fund

49. Parrotfish Poop White Sand—And Lots of It

If you’ve ever sunk your toes into powdery white beach sand, you might owe a thank-you to a parrotfish. These colorful reef dwellers feed on algae by scraping them off coral with their beak-like mouths. In the process, they grind up chunks of coral, digest the algae, and excrete the rest as fine white sand. A single large parrotfish can produce over 800 pounds of sand each year.

This natural sand production helps maintain tropical beaches and contributes to the soft, pristine shorelines in places like Hawaii and the Maldives. So yes, the stuff between your toes may have once been coral and passed through a parrotfish’s digestive system. Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology

50. Toads Can Predict Earthquakes Days in Advance

Long before the ground starts to shake, some toads sense what’s coming. In 2009, researchers studying toad populations in Italy noticed that common toads abandoned their breeding site five days before a major earthquake struck. The event, which measured 6.3 on the Richter scale, was preceded by a sudden drop in toad activity, despite ideal mating conditions. Within days of the quake, the toads returned, suggesting they were responding to environmental cues tied to seismic activity.

Scientists believe the toads might detect changes in electromagnetic fields or shifts in groundwater chemistry caused by rocks under stress. While still not fully understood, the phenomenon is part of a growing field of study on animal behavior and natural disaster forecasting. Toads aren’t the only ones; similar reports involve snakes, cats, and dogs acting strangely before quakes. This research was published in the Journal of Zoology

51. Sharks Can Sense Your Heartbeat—From Several Feet Away

Sharks don’t just smell blood; they detect electric fields generated by the muscle contractions of living creatures, including your beating heart. Using specialized sensory organs called ampullae of Lorenzini, located around their snouts, sharks can pick up tiny electrical impulses from prey hiding in sand or even completely motionless. These electroreceptors are so sensitive that some sharks can detect a heartbeat from over three feet away.

This sixth sense gives sharks a significant edge, especially in murky water where vision and scent may not be sufficient. It’s one reason why lying still won’t necessarily keep you safe from a curious shark; they can still “see” you without ever opening their eyes. This electromagnetic hunting tool is one of the most advanced in the animal kingdom and has been studied in depth by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA)

52. Owls Can Rotate Their Heads 270 Degrees—Without Cutting Off Blood Flow

Owls have an eerie ability to spin their heads up to 270 degrees in either direction, nearly a full circle. But unlike humans, they can do it without snapping arteries or cutting off blood flow to their brains. This is thanks to unique anatomical adaptations: extra-wide arteries, flexible vertebrae, and a specialized bone structure that allows blood to pool and reroute during rotation.

Scientists have discovered that owls have small reservoirs in their neck arteries that act as pressure regulators, keeping blood flowing even when the vessels are constricted. This head-swiveling superpower helps them hunt silently and precisely, locking onto prey without moving their bodies. It’s a biological feat that still stuns neuroscientists and radiologists alike. Johns Hopkins Medicine

The More You Know, the Wilder It Gets

Nature doesn’t just defy our expectations, it reinvents them. From glowing platypuses and immortal jellyfish to poop-sculpting wombats and name-calling bats, animals keep rewriting the rulebook on intelligence, survival, and communication. Every one of these facts challenges how we define emotion, memory, or even identity, and proves that wild doesn’t mean primitive.

So the next time you see a cow, a crow, or an axolotl, don’t just look, wonder. Because the line between “animal” and “genius” might be thinner than you think. Got your own favorite weird animal truth? Send it our way, we constantly search for facts that leave us speechless.