1. The Titanic’s Grand Voyage and Its Doomed Fate

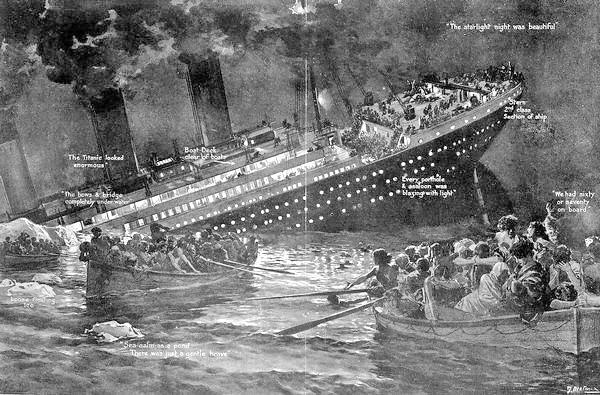

The Titanic was a marvel when it left Southampton on April 10, 1912—a ship of towering steel and polished wood, built to carry 2,224 passengers across the Atlantic to New York. First-class travelers, who paid between $150 and $4,350 for their tickets, lounged in suites with electric lights and fine china, sipping champagne in walnut-paneled dining rooms while orchestras played. Third-class families, who paid around $35, huddled below in steerage, their bunks stacked tight, dreaming of America’s promise through the hum of the engines. Shipbuilders at Harland & Wolff called it unsinkable, a claim trumpeted in newspapers like The Times, sparking awe and confidence as the White Star Line’s flagship steamed westward under Captain Edward Smith’s steady hand. But the Titanic carried more than people—dogs yapped on deck, cats prowled the shadows, birds chirped in cages, and whispers of livestock rustled in the holds, their stories tucked into trunks, kennels, and cargo logs pieced together later from survivors’ fractured tales. [Source: Encyclopedia Titanica]

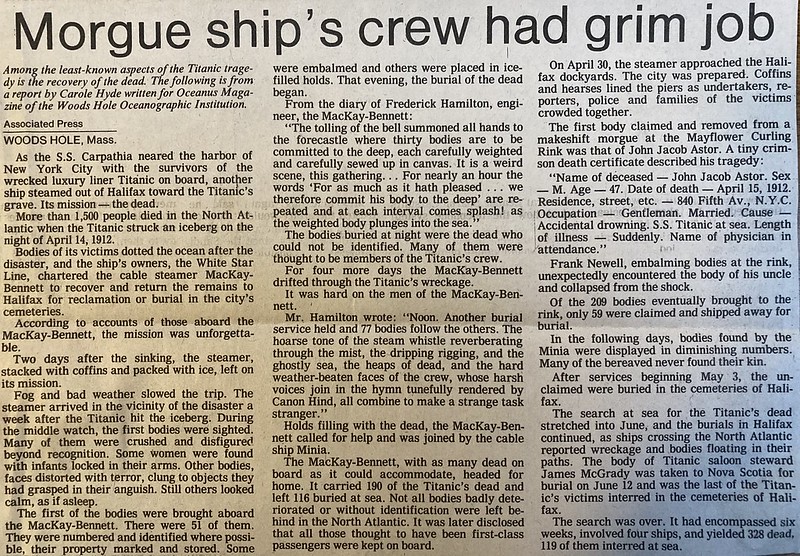

That illusion of safety shattered on April 14 at 11:40 p.m., when an iceberg tore into the hull, its jagged edge slicing through five watertight compartments in a grinding roar heard by lookout Frederick Fleet. By early morning, the ship was gone, swallowed by the North Atlantic’s icy depths, leaving over 1,500 lives lost—men in tuxedos, women in evening gowns, children in nightclothes—all claimed by the frigid dark. Amid the chaos, animals faced the same grim fate: pets whimpered in locked cabins, dogs scratched at kennel bars below, their cries fading as lifeboats rowed away under a starlit sky. Survivors later told The New York Times (April 1912) of the human toll, but quieter accounts emerged—steward John Hart recalled “piteous barks” as he loaded passengers, while others saw feathers drifting in the wreckage, a haunting chorus of loss. This is their story, a hidden chapter of loyalty and despair, preserved in what witnesses endured and history reclaimed, a reminder that the Titanic’s tragedy stretched beyond its passenger list.

2. Why Animals Sailed: Companions and Workers

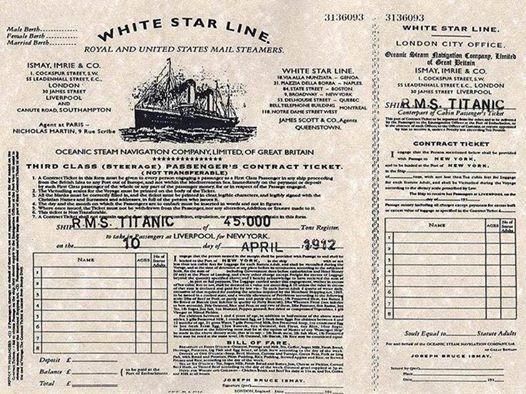

In 1912, the Titanic wasn’t just a liner for humans—it was a floating ark where animals carved their place, driven by the Edwardian elite’s love for pets as symbols of wealth and affection. First-class passengers like Margaret Hays paid fares rivaling a child’s ticket—sometimes $50 or more—for Pomeranians or Pekingese, their fluffy coats brushed daily, as noted in White Star Line’s pet policies. These dogs strutted the promenade or napped in gilded suites, their owners—tycoons and heiresses—flaunting them like jewels. Below, third-class immigrants smuggled scruffy mutts or caged canaries in their meager bags, clinging to these bits of home as they crossed an ocean of uncertainty—perhaps a Lebanese family’s finch trilling memories of Beirut, or an Irish boy’s pup curled in a sack. The ship hummed with their presence, a menagerie woven into its steel heart, from polished decks to steerage’s shadows. [Source: White Star Line Archives]

Beyond status, animals earned their keep aboard—ship cats like Jenny, a tabby recalled by stewardess Violet Jessop, stalked the decks with keen eyes, pouncing on rats that gnawed at grain sacks in the cargo holds, a vital task on a vessel stocked for weeks at sea. Whispers of chickens clucking in crates for fresh eggs floated among the crew—possibly a dozen hens nestled near the galley—though no manifest confirms it, while a rumored cow for milk stayed a fanciful sailor’s yarn. Crewmen like John Hutchinson fed kennel dogs—Great Danes and Airedales—scraps from the Ritz-like kitchens, their daily walks on the poop deck a ritual that outshone steerage’s grim quarters. From prestige to purpose, these creatures shaped the Titanic’s life—until April 14’s disaster turned their voyage into a desperate fight no claw or paw could win, their roles drowned in the chaos of a sinking giant.

3. The Lucky Ones: The Animals That Never Boarded the Titanic

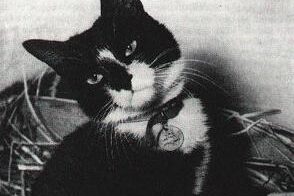

Some animals escaped the Titanic’s fate by never setting foot aboard, their stories a quiet twist of fortune against the ship’s doomed plunge. Frisky, a black-and-white cat who roamed the Belfast shipyard at Harland & Wolff, was a mascot to workers riveting the hull—her purrs a comfort amid the clang of steel as they hammered the Titanic into shape. Just before the April 10 departure, she birthed kittens and hauled them off the gangway, one by one, her green eyes fixed on shore as if sensing the peril ahead—a mother’s trek across the dockyard mud to safety. Shipyard tales, later captured in the Titanic Historical Society Journal of 1993, called it an omen—her instinct sparing her from the icy waves while the ship sailed on with its 2,224 souls. Her absence became a legend of eerie luck, a feline survivor who never faced the sinking’s dark roar. [Source: Titanic Historical Society]

Others dodged the voyage by chance or fate’s whim—a first-class family, possibly the Carters, left a sleek greyhound named Dash at Southampton, its leash forgotten on the pier as they boarded, a decision noted in passing by The New York Times, April 1912 reporters piecing together survivor scraps after the tragedy. A sturdy draft horse—chestnut coat gleaming—meant for the cargo hold to haul goods in New York, missed its crate due to a shipping snag—White Star Line records hint at a delayed manifest, sparing its hooves the hold’s flood. These animals sidestepped the panic of that night—the creaking decks tilting starboard, the lifeboats dangling precariously, the cold that swallowed all—living on as silent victors while the Titanic’s barks and neighs vanished into the North Atlantic. Their tales whisper a soft counterpoint to the cacophony of loss, a stroke of fortune in a narrative heavy with the drowned and the damned.

4. Shadows of the Voyage: Third-Class Pets Below Deck

Third-class passengers, often immigrants bound for new lives, carried more than hope in their battered bags—small dogs like scruffy terriers, birds like canaries in wire cages, or kittens hid among their belongings, unlisted on any manifest but real to those who clutched them close. These pets, unlike the pedigreed hounds of first class, were humble companions—perhaps a mutt with a wagging tail for an Irish lad or a chirping finch for a Swedish mother—kept secret in steerage’s dim, crowded cabins where bunks creaked under the weight of dreams. Families like the Sages—eleven souls packed tight—might’ve hushed a kitten’s mews with scraps of bread, while a Lebanese widow cradled a birdcage, its song a thread to a home left behind. Their presence was a whispered comfort amid the ship’s hum, a lifeline as the Titanic steamed toward its fate. [Source: Immigrant Stories]

Their secrecy was a quiet rebellion against the ship’s rules—no kennels or space existed for steerage animals, leaving them tucked in trunks or cradled in arms as the voyage unfolded, their owners dodging stewards’ eyes in the narrow passages below. Survivor accounts later spoke of faint barks or trills echoing through G Deck’s gloom—Ellen Shine recalled a puppy’s yip silenced by the flood—details lost when the iceberg struck on April 14, drowning these small lives with the same ruthlessness that claimed over 1,500 humans. The Sages’ kitten, the widow’s finch—they sank in their hidden nooks, no lifeboats to lift them from the rising tide that breached the gates locking third-class below. These pets’ stories are a shadowed testament—love persisting in the meanest quarters, snuffed out by a disaster that cared nothing for class or the fragile bonds they held dear. [Source: Titanic Voices]

5. Crew’s Silent Allies: Pets of the Working Ship

The Titanic’s crew—over 900 stewards, firemen, and officers—had their own animal partners beyond the first-class kennels, woven into the ship’s daily grind of sweat and steel. A crewman like John Hutchinson, who tended the F Deck kennels, might’ve kept a wiry terrier named Jack in his bunk, its yaps a welcome break from the sawdust and hammer of his carpenter’s rounds. Down in the boiler rooms, firemen whispered of rats—gray scamps they named like “Soot” or “Coal”—fed scraps of bread as mascots to ease the sweaty, coal-dusted hours stoking the ship’s furnaces, a tradition noted in maritime lore. These creatures were the unsung heartbeat of the crew’s world, their presence a quiet rhythm amid the clanging pipes and hissing steam that powered the Titanic’s westward course. [Source: Titanic Historical Society]

Their fates mirrored the crew’s grim end—when the iceberg hit at 11:40 p.m., these allies drowned in flooded quarters or clung to tilting decks as water surged through the lower levels, no lifeboats sparing them from the chaos that claimed over half the ship’s hands. A steward’s kitten might’ve purred in a galley corner—Violet Jessop recalled a tabby’s shadow—only to vanish as the sea roared in, while a lookout’s imagined bird, perched near the crow’s nest, would’ve fluttered into the night with no perch to reclaim. Their stories faded without fanfare—Jack’s barks, Soot’s skitter—lost as the Carpathia plucked human survivors from the waves, leaving the crew’s companions behind. These pets were the ship’s working soul, their silent loyalty a thread in the fabric of a night that spared neither rank nor fur in its relentless, icy grip. [Source: Encyclopedia Titanica]

6. The Titanic’s Secret Passengers: Who Brought Animals Aboard?

The Titanic carried a roster of wealth—names like Margaret Hays, a socialite with her Pomeranian, Lady, tucked in her cabin, and Henry Harper, whose Pekingese, Sun Yat-Sen, shared his first-class quarters beneath crystal chandeliers that glittered like stars. Elizabeth Rothschild kept her unnamed Pomeranian close, its tiny paws pattering on polished floors, while William Carter’s Airedale Terrier and King Charles Spaniel paced the kennel below, their barks mingling with the ship’s steady hum. Anna Isham walked aboard with her Great Dane, a towering companion she refused to leave, its shadow looming on deck under the April sun. Frederic Spedden, a New York millionaire traveling with his wife Daisy and son Douglas, brought a small dog—possibly a terrier—kept in their suite, a detail family diaries later revealed. Third-class passengers hid birds or kittens in their bags, their pets unlisted but real—a secret heartbeat pulsing through steerage’s depths. [Source: Encyclopedia Titanica]

Other prominent families joined the menagerie—Thomas Andrews, the ship’s designer, was rumored to have a dog aboard, perhaps a wiry terrier meant as a gift for his wife, Helen, left in his A Deck cabin amid blueprints and a steaming teapot, though accounts waver on its truth. According to the Titanic Inquiry Project, George Widener, a Philadelphia tycoon, might’ve traveled with a pet too—a lapdog’s yip echoed in survivor whispers, though no manifest pins it down, its existence a gilded question mark in the saloon’s glow. These animals, from pedigreed hounds to steerage stowaways, were the Titanic’s hidden passengers, their owners weaving them into the voyage’s fabric—silk for some, burlap for others—until the night of April 14 tore it apart, as per passenger logs studied by historians. From Spedden’s terrier to Isham’s Great Dane, each pet carried a story, a bond that faced the same icy fate as the ship itself, sinking into darkness with whimpers and silence.

7. Second-Class Shadows: Pets of the Middle Tier

Second-class passengers, caught between first-class splendor and third-class grit, brought their own pets aboard, less flaunted but no less loved—Lawrence Beesley, a schoolteacher who survived, wrote in The Loss of the SS Titanic of a widow named Emily Richards cradling a wiry terrier named Pip in their shared cabin. The Collyer family—Harvey, Charlotte, and little Marjorie—might’ve tucked a spaniel called Bess into their luggage, its floppy ears brushing the narrow bunk as they dreamed of a farm in Idaho. These pets lacked the pedigrees of first-class hounds—no kennel pampering for them—but shared tight quarters on B Deck, their owners finding solace in their barks and warmth amid the ship’s steady roll. A young clerk, James Moody, recalled a caged finch trilling in a second-class berth, its tailor owner whistling back during quiet evenings—small joys in a middling world.

Their stories faded into the margins as the Titanic sailed, overshadowed by the elite’s grandeur—Pip’s yaps drowned by the saloon’s orchestra, Bess’s snores lost in the library’s hum—yet they were as real as any pedigreed pup, their presence a thread in the voyage’s quieter corners. When the iceberg struck on April 14, these animals stayed close—not kenneled but nestled in cabins or bags—their fates tied to owners who faced the same chaos: splintered decks, frantic shouts, and lifeboats that rarely welcomed pets. By dawn, Pip, Bess, and that finch were gone, drowned in flooded cabins or left behind as Charlotte rowed away with Marjorie, their loss a muted ache in a disaster that spared few, regardless of class or comfort—survivors like Beesley later mourned them in ink, a whisper against the roar of the night’s toll.

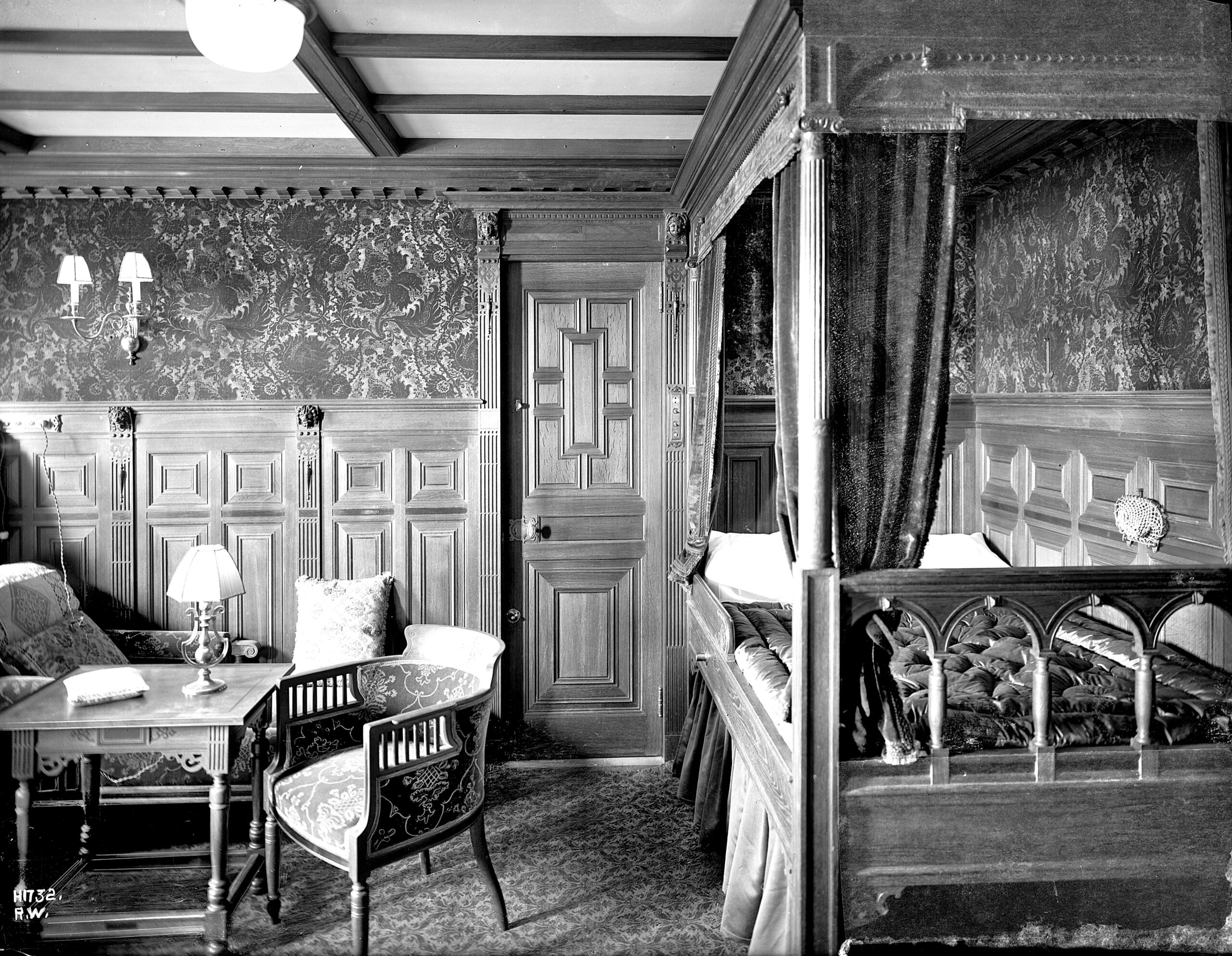

8. A First-Class Life: The Titanic’s Luxury Kennels and Pet Accommodations

The Titanic’s kennel on F Deck was a haven for first-class dogs—Great Danes, Terriers, Spaniels—where a crewman like John Hutchinson fed them and took them for daily walks, their paws clicking on the poop deck under a crisp April sky as gulls wheeled overhead. It was a setup so fine that a dog show was planned for April 15, a celebration of pedigree that never came—owners like William Carter eyed ribbons for his Airedale and Spaniel, their coats gleaming from daily brushes. These dogs lived well, dining on scraps from the Ritz-like kitchens—roast beef and biscuits—while their owners, clad in furs and top hats, popped in between caviar courses to scratch their ears. For the wealthy, pets were part of the luxury, cared for almost as well as the passengers themselves—a pampered pack in a floating palace of steel and silk.

Smaller dogs stayed in cabins—Lady with Margaret Hays, Sun Yat-Sen with Henry Harper—close enough to save when disaster struck, their plush beds nestled beside velvet curtains and mahogany desks, a contrast to the kennel’s steel cages below. Third-class pets had no such luck, hidden in crates or bags with no official space—factory workers or farmers keeping them secret under coarse blankets—while a piglet in a musical case popped up in survivor tales, likely Edith Rosenbaum’s mechanical toy wound to play “Maxixe,” though some swore it squealed, a quirky mystery never fully solved, as per The New York Times accounts from the time. The divide was stark: first-class animals lounged in comfort—Lady napping by a fireplace, Spaniels sprawled on rugs—while others scraped by, a disparity erased when the night of April 14 leveled them all, the rising water swallowing both privilege and privation in its cold, impartial flood.

9. The Night of Terror: What Happened to the Animals When the Titanic Sank?

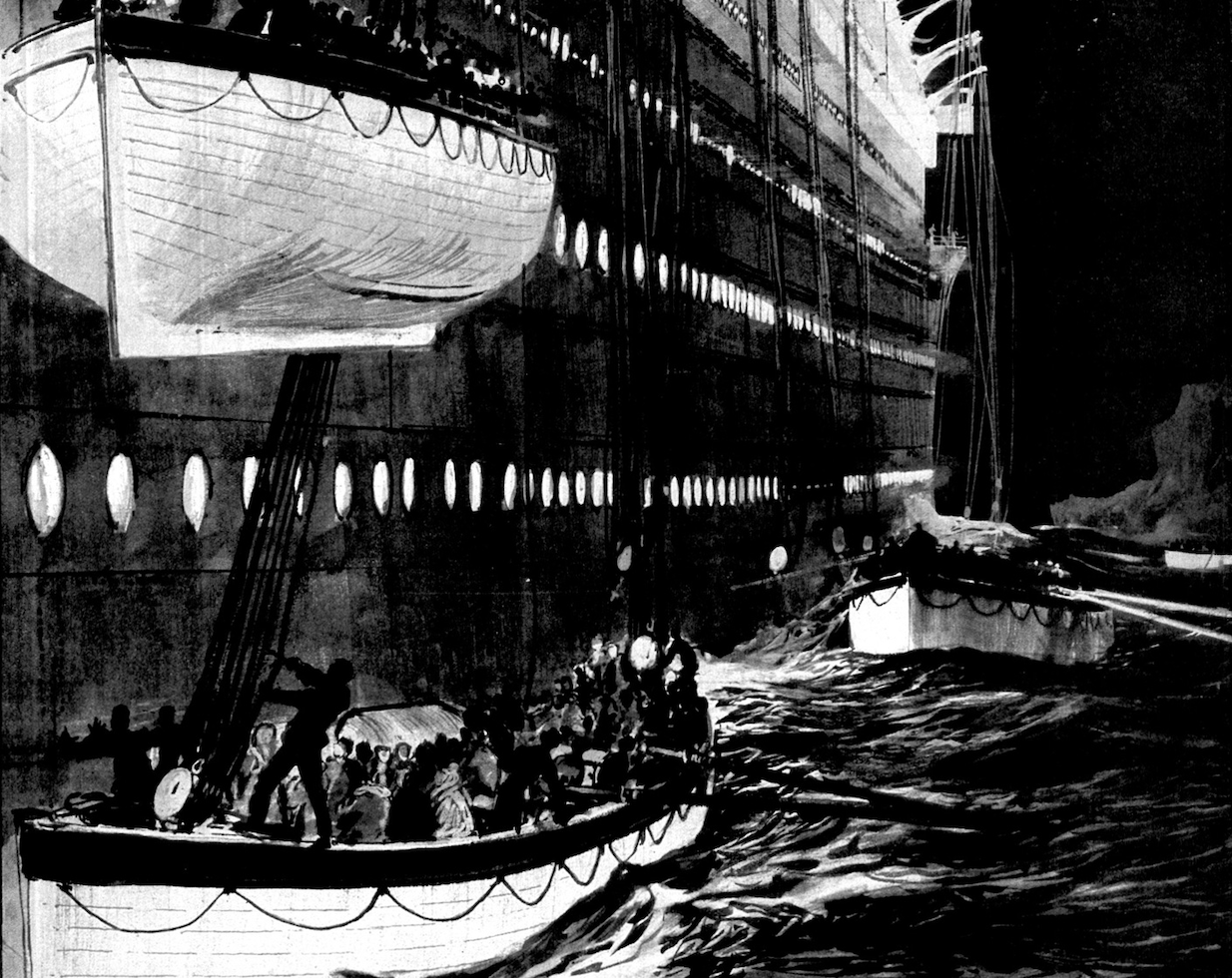

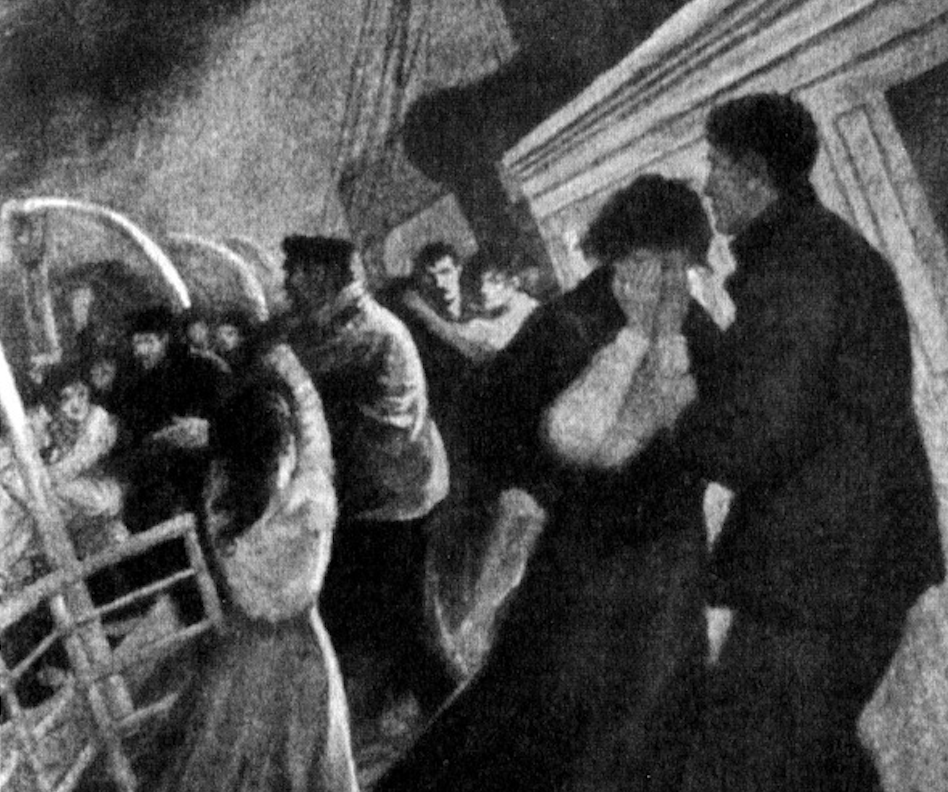

At 11:40 p.m. on April 14, the Titanic hit an iceberg, and the ship’s fate turned grim, the collision’s shudder rattling china in the dining saloon as passengers froze mid-bite, forks clattering to the floor. In the kennels, dogs barked as water flooded in—Great Danes and Terriers trapped until someone, maybe a crewman like John Hutchinson, unlocked the cages, his hands trembling as the ship listed starboard, bulkheads groaning under pressure. They ran, paws pounding the tilting deck, their coats soaked as they darted past screaming passengers scrambling for lifeboats under flickering electric lights—William Carter’s Airedale lunging up stairs, Anna Isham’s Dane lumbering beside her. Survivors later told of the sound—barks cutting through the night, a desperate plea no one could answer, as mentioned in newspaper reports days later, their howls a haunting chorus against the ship’s death throes.

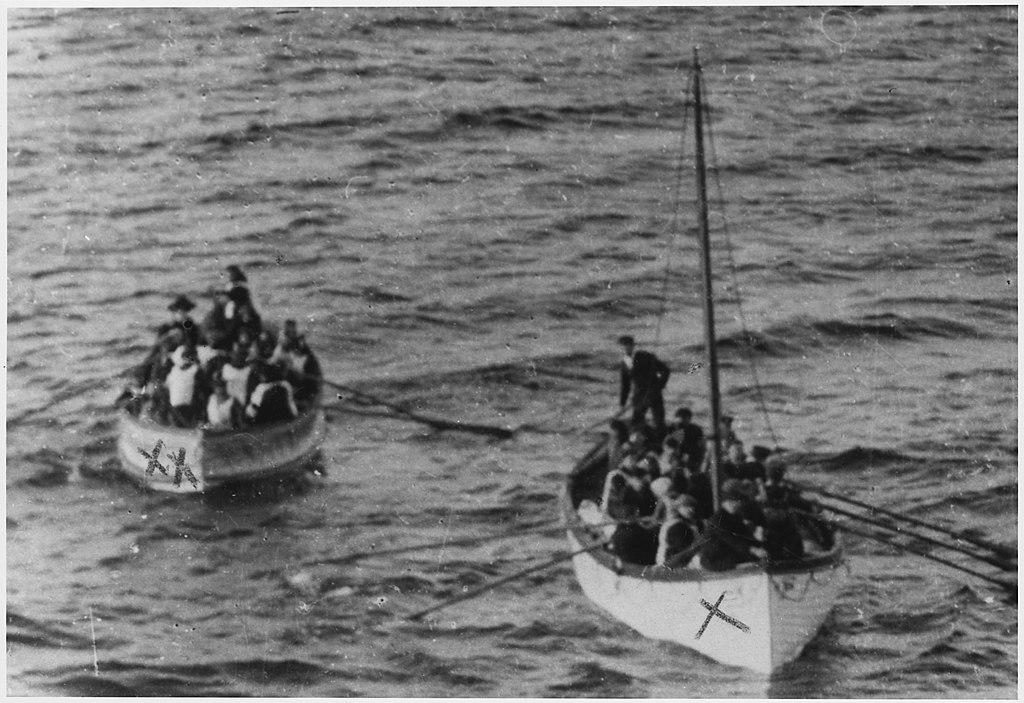

Anna Isham stood with her Great Dane, refusing a lifeboat that wouldn’t take him—her gray coat drenched as she gripped his collar, a stoic figure against the pandemonium of shouting officers and weeping women—while another begged for her spaniel, its leash slipping as officers barked “women and children only.” In cabins, birds fluttered in cages—canaries and finches beating against wire—cats hid under beds, their eyes wide as water rose, and rats scurried from the holds, their squeaks lost in the din. When the ship broke apart at 2:20 a.m., animals fell into the sea—dogs paddled briefly in the 28-degree water before the cold seized them, their end a silent toll beneath the human wails, recalled by those who watched from lifeboats as the lights blinked out, the night swallowing fur and feathers alike.

10. Lady the Pomeranian: A Socialite’s Tiny Survivor

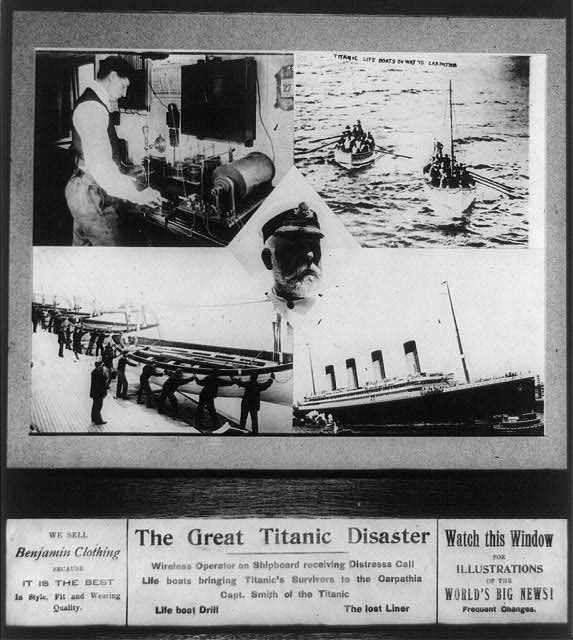

Margaret Hays, a 24-year-old New York socialite, boarded the Titanic with her Pomeranian, Lady, a small dog she kept in her first-class cabin rather than the kennel, its fluffy coat a constant beside her silk dresses and pearl necklaces. When the ship struck the iceberg on April 14, 1912, Margaret didn’t waste time—she grabbed Lady, wrapped her in a blanket against the biting wind, and headed for Lifeboat 7 as alarms blared through the corridors, her heels clicking on the polished wood past stunned passengers. The crew, focused on loading women and children under the dim glow of deck lights, didn’t notice the tiny bundle in her arms—Lady’s yips muffled as Margaret stepped into the boat, a detail survivors later shared with investigators reviewing the disaster’s frantic moments. Her quick resolve saved them both as ropes creaked and the ship groaned beneath her.

Rescued by the Carpathia hours later, Margaret stepped aboard with Lady still clutched close, a sight that stunned fellow passengers who assumed no animals had survived—their gasps mingling with the dawn’s chill as the little dog shivered in her arms. Back in New York, Lady lived on as a quiet reminder of the disaster, her survival noted briefly in newspaper accounts from April 18, 1912—The New York Times called her “a fluff of fur against the horror,” a living relic of a night that took over 1,500 souls. For Margaret, Lady was more than a pet—she was a piece of home pulled from the wreckage, a trembling link to a life before the screams and icy plunge. Her story stands out as a rare victory, a testament to how love and a little luck could defy the odds when the Titanic’s grand promise turned to terror under a starless sky.

11. The Unnamed Pomeranian: Rothschild’s Defiant Rescue

Elizabeth Rothschild, traveling first-class with her husband Martin, brought her Pomeranian aboard the Titanic, keeping it in her cabin instead of the kennel, its tiny bell jingling as it scampered around their C Deck suite amid trunks of Parisian finery. When the ship hit the iceberg, Martin urged her to a lifeboat—his voice steady amid the rising panic of clanging bells—but Elizabeth refused to go without her dog, tucking the Pomeranian, its name never recorded, under her coat and boarding despite crew protests in the frantic evacuation. Survivors recounted her resolve days later—her fur collar hiding the dog’s shivering frame as she stepped into Lifeboat 6, the night swallowing Martin’s pleas—a bold move that paid off; the dog stayed hidden, and both reached safety, an improbable win amid the chaos.

Martin didn’t make it—he perished as the ship sank, his last sight perhaps Elizabeth’s silhouette against the tilting deck—but she and her Pomeranian were pulled aboard the Carpathia, her gloved hands cradling its warmth as dawn broke over the rescue, the sea still littered with wreckage. Passengers shared the tale with reporters afterward—The New York Herald noted her “quiet courage,” the dog a lifeline as she faced widowhood alone, her husband’s absence a shadow beside her on the deck. The Pomeranian lived on with her in New York, a silent survivor of a tragedy that stole so much—its soft fur a balm against the grief etched in her eyes when she stepped ashore. Elizabeth’s refusal wasn’t just stubbornness—it was a desperate act of love, preserving one small life when the Titanic’s grandeur crumbled, a sharp note of defiance cutting through a night of despair.

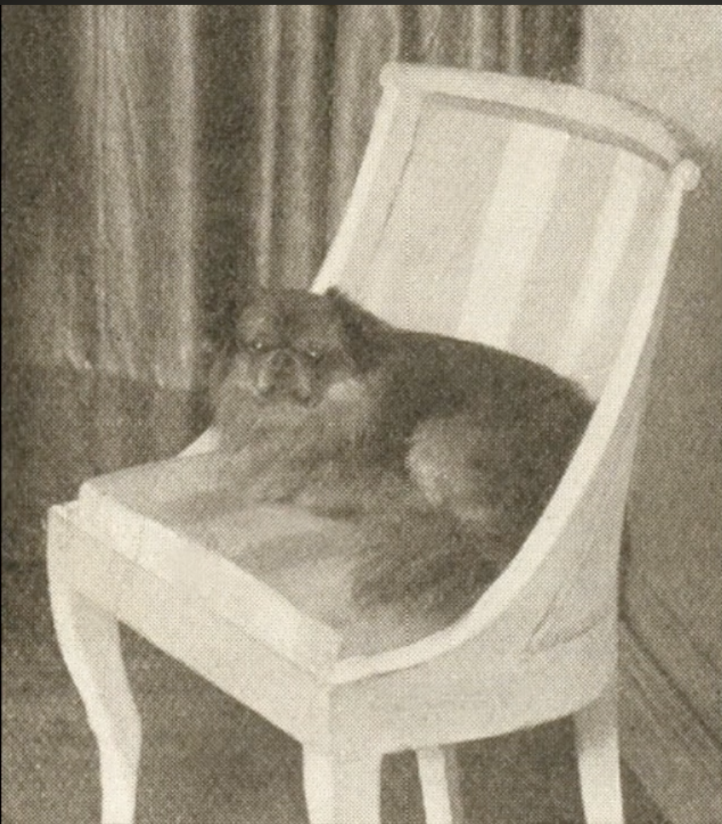

12. Sun Yat-Sen: The Pekingese Prince of Lifeboat 3

Henry Sleeper Harper, heir to the Harper & Brothers publishing fortune, stepped onto the Titanic with his wife Myra and their Pekingese, Sun Yat-Sen—a dog named for China’s revolutionary leader, its silky fur a fixture of their travels from Paris to New York. Kept in their first-class cabin on C Deck, Sun Yat-Sen lounged on velvet cushions—its dark eyes peering out as Henry read proofs by lamplight, Myra adjusting her hat nearby—its small size a perfect fit for the suite’s tight quarters. When the iceberg struck on April 14, Henry wasted no time—he scooped up Sun Yat-Sen, bundled him in a coat against the biting wind, and joined Myra in Lifeboat 3 as the ship began to tilt, its bow dipping ominously. The crew, busy lowering boats with ropes snapping taut, overlooked the dog—a fact Henry later confirmed to investigators, his calm voice recounting the night’s blur.

The Carpathia rescued them hours later—Myra clutching Henry’s arm, Sun Yat-Sen nestled close—and Henry told reporters the dog slept through the ordeal, a serene presence amid the panic—The New York Times dubbed him “the prince who napped through disaster,” his snores a quiet counterpoint to the screams. Back in New York, the Pekingese lived on, padding through their Fifth Avenue mansion—a survivor whose royal name matched his charmed fate, untouched by the icy waves that claimed over 1,500 lives. Henry and Myra’s quick thinking—and their first-class status—gave Sun Yat-Sen a chance others didn’t have, his tiny form slipping past the chaos of sinking decks and overloaded boats. His story is a quiet marvel, proof that privilege and timing could tip the scales even for a pet, a small thread of luck woven through the Titanic’s tapestry of loss.

13. The Kennel’s Doomed: The Larger Dogs Left Behind

The Titanic’s kennel on F Deck housed the bigger dogs—William Carter’s Airedale Terrier and King Charles Spaniel, Anna Isham’s Great Dane—each a beloved companion to their first-class owners, their deep barks a familiar echo through the ship’s steel corridors. A crewman, likely John Hutchinson, tended them daily, walking them on the poop deck under a crisp sky—Great Danes stretching their long legs, Spaniels bounding after scraps—and feeding them roast lamb from the galley, a routine that made the kennel a lively spot until April 14. When the ship hit the iceberg, water flooded the lower decks fast—its icy surge rattling the cages as the dogs howled, trapped in their enclosures below the waterline. Survivors speculated to the Titanic Historical Society Journal that Hutchinson unlocked the cages as the ship tilted—his boots slipping on wet floors—giving them a fleeting chance to bolt up stairs, onto the deck, barking for owners lost in the fray of panic and smoke.

The freed dogs ran—up staircases slick with seawater, onto the listing deck—their coats matted as they dodged passengers shoving toward lifeboats, their barks piercing the night’s din of creaking steel and human cries. Billy Carter, William’s son, cried in a lifeboat—his Airedale’s absence a knife in his chest, a moment his family shared with The Philadelphia Inquirer after rescue—his father’s wealth powerless against the flood that roared through F Deck. Anna Isham stayed with her Great Dane—its massive frame too large for escape—her silhouette fading as waves rose. Most didn’t make it—drowned below in the kennel’s dark or swept into the freezing sea when the ship split at 2:20 a.m., their owners’ plans for an April 15 dog show drowned with them—a heartbreaking echo of loyalty lost to a night where size and location sealed their doom beneath a starless sky.

14. Anna Isham and Her Great Dane: Loyalty Beyond Life

Anna Elizabeth Isham, a 50-year-old Chicago heiress, brought her Great Dane aboard after a European visit, housing it in the kennel but checking on it often—her devotion clear to deck onlookers who saw her gray-gloved hand stroke its brindled fur as it towered beside her. When the iceberg hit, she raced to F Deck—finding her dog amid rising water, its deep barks reverberating as the ship shuddered—and faced a lifeboat that refused its bulk—a rule survivors later affirmed in Titanic Voices, her pleas drowned by the shouts of officers. Witnesses last saw her on deck, hand resting on its head, serene as the ship lurched—her lavender scarf fluttering in the wind, a scene etched in The Chicago Tribune’s post-rescue report. She stood firm while others fled, her choice a testament to a bond forged over years of companionship across continents.

She chose the latter over life without him—her calm resolve unshaken as the deck tilted and water lapped her boots, witnesses recalling her stillness amid the screams and clanging bells as passengers shoved past in terror. Her body was never found, nor was his—both lost to the Atlantic’s depths when the ship sank at 2:20 a.m., the Dane’s massive frame sinking beside her into the icy dark that claimed over 1,500 souls. Anna’s story, pulled from ship records and survivor tales—a woman who valued her dog’s life as much as her own—stands as one of unshakable loyalty amid split-second decisions. In a night where survival hung on fleeting chances—lifeboats swinging, ropes snapping—she stood resolute, her companion’s amber eyes her last sight, a tale of devotion cutting through the cold facts of the disaster like a beacon in the void.

15. Helen Bishop and Frou-Frou: A Heartbreaking Farewell

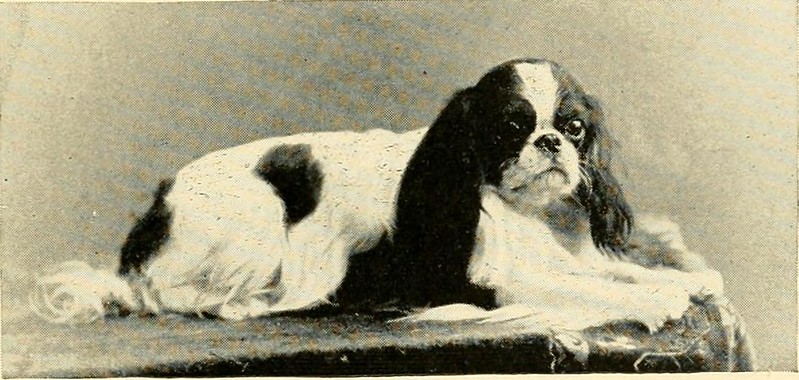

Helen Bishop, a first-class passenger from St. Louis, boarded the Titanic with her husband Dickinson and her Toy Spaniel, Frou-Frou—a dainty dog she kept in their cabin, its silky ears brushing her silk skirts as they dined in the saloon under chandeliers’ glow. Frou-Frou was her shadow, a constant companion during the voyage—curling up beside her on a velvet chaise as the ship sailed smoothly through its first days, its tiny bell tinkling with each sway of the Atlantic’s waves. But on April 14, when the iceberg struck—its crunch echoing through the hull—everything changed; alarms pierced the night, and Helen and Dickinson rushed to the lifeboats, Frou-Frou in tow, his leash taut in her trembling hand. She tried to bring him aboard Lifeboat 7, pleading with the crew as tears welled, but they refused—too many people, too little space—his teeth tugging at her dress as she stepped away, a moment she later sobbed to The New York Times.

Left with no choice, Helen handed Frou-Frou over—tears streaming as she boarded the lifeboat, her husband’s arm around her as she watched him tremble on the deck, a small silhouette shrinking against the chaos of shouting officers and swinging davits. The boat lowered into the dark—Dickinson whispering comfort—but Frou-Frou didn’t make it, trapped in their C Deck cabin’s plush confines or swept into the sea as the ship sank at 2:20 a.m., his fate sealed by the cold that claimed over 1,500 lives. Helen’s grief lingered; she spoke of the moment often—her words recorded by survivors who heard her sobs on the Carpathia—The St. Louis Post-Dispatch called it “a wound deeper than the ocean.” For Helen, he wasn’t just a pet—he was a piece of her heart, left behind in a night that spared her body but broke her spirit, a loss sharper than the iceberg’s edge.

16. William Carter’s Lost Dogs: A Family’s Double Loss

William Carter, a wealthy mining executive, boarded the Titanic with his wife Lucile, their children, and two dogs—an Airedale Terrier and a King Charles Spaniel—their wagging tails a delight in their first-class suite’s opulent glow on C Deck. These pets, beloved by the family—especially young Billy—stayed in the F Deck kennel under the care of a crewman, their barks greeting Billy each morning as he slipped them bacon from the breakfast tray amid the clink of silver spoons. The Airedale was Billy’s favorite—a lanky companion who’d chased him across their Philadelphia estate’s lawns—while the Spaniel’s soulful eyes charmed Lucile’s tea parties with its gentle nudge. But when the ship hit the iceberg on April 14—the jolt shattering glass—the kennel’s low location spelled doom; the Carters made it to Lifeboat 4, but the dogs couldn’t follow, a fact William later noted in an insurance claim filed after the sinking.

Billy’s tears stained the lifeboat as it pulled away—he knew his Airedale was gone, his small hands gripping the gunwale as Lucile hushed his cries under a borrowed shawl, her own eyes wet with the double loss as the ship’s lights flickered out. The dogs either drowned in their cages—water roaring through F Deck’s steel lattice—or ran free when someone unlocked the kennel, only to perish in the freezing waves as the Titanic split apart—The Philadelphia Inquirer reported Billy’s wails as “a child’s world ending” amid the night’s chaos. William’s claim pegged their worth at $300—a cold figure against Billy’s loss of his truest friends, their muddy pawprints a memory on the estate’s grass. The Carters survived, stepping onto the Carpathia’s deck, but the absence of those loyal paws left a hollow ache—a family fractured by a night that spared their lives but not the companions who’d bounded through their gilded days.

17. The Animals That Never Boarded: Fate’s Quiet Mercy

Frisky, a black-and-white cat, roamed the Titanic during its construction in Belfast—a familiar sight to workers at Harland & Wolff, her purrs a soft counterpoint to the hammers shaping the ship’s steel ribs as rivets clanged into place. Just before the April 10 departure, she had kittens—was seen carrying them off, one by one, refusing to return—her green eyes glinting as she hauled her litter across the gangway to the shipyard’s muddy edge, a mother’s trek to safety. Workers later told historians it felt like a sign—a cat sensing trouble where humans saw only progress, as mentioned in accounts from the time—she’d dodged the icy fate awaiting the 2,224 aboard. Frisky’s escape spared her and her kittens from the disaster—a stroke of luck that became a haunting footnote in Belfast’s lore, whispered over pints in dockside pubs as the ship’s absence sank in.

Other animals dodged the voyage too—a first-class family, possibly the Carters, left a sleek greyhound named Dash behind at Southampton, its lead coiled on the pier as they boarded—its lean frame spared the kennel’s flood—a decision noted by The New York Times reporters sifting through survivor scraps after the sinking. A sturdy draft horse—chestnut coat gleaming—meant for the cargo hold to haul goods in New York, missed its crate due to a clerical error—White Star Line records hint at a delayed manifest—its hooves never touching the ship’s dark hold. These near-misses saved lives that would’ve faced the deluge or the sea’s chill—creatures living on while the Titanic carried hundreds to their end under a moonless sky. Their absence was a silent reprieve—a stark contrast to the barking, chirping chaos that drowned in the North Atlantic’s depths on April 15, 1912.

18. The Forgotten Rats and Small Pets: Unseen Victims

Rats scurried through the Titanic’s shadows—a common sight on ships of the era, thriving in the cargo holds and food stores—dozens, maybe hundreds, of gray scamps gnawing at sacks of oats and skittering along pipes below decks with twitching whiskers. No one counted them, but their presence was certain—their beady eyes glinting in the dim light of E Deck as stewards tossed crumbs their way, a silent crew keeping the ship’s stores in check from bow to stern. When the iceberg hit—its crunch reverberating through the hull—they likely fled the flooding lower decks, racing up stairwells as water surged, only to find no escape amid the chaos of tilting floors and creaking steel. They drowned with the ship—unnoticed casualties of a disaster that spared no corner—a fate historians later pieced together from maritime norms of the time’s rat-ridden vessels.

Small pets faced a similar end—third-class passengers, often immigrants like the Sage family of eleven, brought canaries, rabbits, or kittens—hidden in wire cages or burlap bags—their soft chirps or mews a comfort in steerage’s cramped, musty gloom beneath the ship’s opulent upper decks. These weren’t the pedigreed dogs of first class; they were humble treasures—perhaps a lop-eared bunny for a child’s lap or a finch for a weary mother’s song—undocumented and overlooked by the ship’s manifest, their owners clutching them as the Titanic sailed west. Survivors rarely mentioned them, but a few recalled birds chirping as water rose—Ellen Shine heard a canary’s trill fade—per passenger interviews after the rescue, a faint note swallowed by the flood. With no kennels or lifeboats, they perished—trapped in cabins or swept away—a quiet toll in a night that roared with human loss, their fragile lives lost to the sea’s relentless grip.

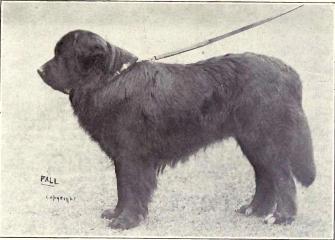

19. Rigel the Newfoundland: Hero or Myth?

Rigel, a Newfoundland said to belong to First Officer William Murdoch, stars in a tale of bravery—swimming through icy water after the sinking, barking to guide the Carpathia to a lifeboat—his deep woofs cutting through the night’s silence like a foghorn in the dark. The story claims he stayed afloat for hours—his thick black fur and barrel chest defying the 28-degree cold until rescue at dawn—a legend that splashed across newspapers like The New York World in late April 1912, painting him as a massive savior amid the wreckage. It’s a gripping image—a hulking dog, a hero in the shadows—credited with saving lives when hope was nearly gone, his stamina a beacon as survivors shivered in open boats under a starless sky. But no survivor testimony confirms it—and Murdoch died that night—leaving Rigel’s tale dangling between fact and fable in the chaos of April 15.

Historians debate Rigel’s existence—no passenger or crew list names him, and Newfoundland dogs—though common on ships for their strength—aren’t tied to Murdoch in official records, as per studies of the disaster by The Titanic Historical Society. The kennel’s dogs drowned or ran loose—Murdoch too busy launching boats, his last act lowering Lifeboat 1—to tend a pet, his fate sealed by a gunshot or the waves, accounts conflicting as the ship split apart. The tale likely grew from grief and imagination—a comforting myth spun by a public desperate for heroes amid the wreckage’s grim tally of over 1,500 lost. If real, Rigel would’ve been kenneled on F Deck—his fate sealed like other large dogs—yet his story endures, a flicker of hope that even in the Titanic’s darkest hour, an animal might’ve fought back against the odds, barking through a century’s memory.

20. The Piglet in the Case: Fact or Fable?

Among the Titanic’s oddest tales is that of a piglet—supposedly smuggled aboard in a musical case by Edith Rosenbaum, a first-class fashion writer—her flair for drama as sharp as her Parisian gowns and feathered hats. She carried a toy pig that played music—a gift from her mother, its tinny “Maxixe” tune a quirky keepsake—and when the ship sank on April 14, Edith clutched it as she boarded Lifeboat 11, winding it to calm crying children amid the creak of lowering ropes and the ship’s groaning steel. Some survivors swore they heard a real piglet squealing—its high-pitched cries piercing the night’s chaos—but others dismissed it as her mechanical toy—a detail debated after the Carpathia docked, a puzzle The New York Times chewed over in survivor yarns. The mix-up fueled a quirky legend in a night of grim reality—a whimsical twist amid the screams and splintering decks.

Edith leaned into the tale—telling reporters she’d saved her “lucky pig”—though she clarified it was mechanical—her flair turning a toy into a saga—her words to The New York Herald spinning the story wider as she stepped ashore in her sodden furs. Witnesses from Lifeboat 11 recalled the music—not a live animal—yet the yarn grew—perhaps a real piglet hid among the chaos, a stowaway snuffling in the dark—or perhaps imagination spun a gadget into a pet amid the panic of sinking decks and icy waves. No livestock was officially aboard—making the toy explanation more likely—Edith’s mother had given it as a charm after a car accident, a talisman she clung to as the Titanic split at 2:20 a.m. The piglet—real or not—became a footnote—a spark of whimsy in a disaster that left little room for light—its tune a faint echo against the night’s overwhelming roar of loss.

21. The Ship Cats: Silent Hunters Lost Below

The Titanic likely carried at least one ship cat—a maritime staple for keeping rats in check—Violet Jessop, a stewardess, remembered a tabby named Jenny who roamed the galleys and corridors—her amber eyes glinting as she hunted pests threatening the food stores with swift paws. Jenny had kittens before the voyage—possibly stashed in a nest of rags below deck—and was a quiet presence as the ship sailed from Southampton—her soft tread padding past the clatter of pots in the kitchen, her tail flicking through shadows. Crewmen tossed her bits of fish from the day’s catch—her purrs a gentle rhythm against the engines’ drone—a guardian of the larders keeping the ship’s provisions safe. On April 14, when the iceberg struck—she was likely in the lower levels—E or F Deck—where water flooded first—sealing her fate with no chance to flee the rising tide that roared through the hull.

No one saw Jenny or her kittens escape—and survivors didn’t mention cats among the lifeboats—the rising water would’ve trapped them—their silent work undone as it surged through the galley’s steel seams—drowning her nest in the dark with a swift, cold rush. Violet later wrote of Jenny’s loss in her memoirs—a passing note that hints at the cat’s role and end—her tabby coat sodden—her kittens’ faint mews silenced by the flood that claimed over 1,500 lives in the early hours of April 15. Ship cats were unsung crew—vital yet invisible—slipping through shadows to keep the stores safe from gnawing rats. Their deaths added to the Titanic’s unseen toll—a small, soft tragedy beneath the human chaos—lost to the waves without a trace—their hunt ending in a night that spared neither claw nor courage as the ship sank into silence.

22. The Birds in Cages: Third-Class Treasures

Third-class passengers—many immigrants bound for America—brought more than clothes in their battered trunks—some carried birds—like canaries or finches—in wire cages—their trills a fragile echo of home in steerage’s dim—musty air beneath the ship’s gleaming upper decks. These weren’t luxury pets but cherished companions—their songs a comfort for families like the Sages—eleven strong—facing an uncertain future—their cages swaying with the ship’s roll as mothers hushed children to sleep amid the creak of bunks. No passenger list names them—but the cramped cabins likely rang with faint chirps—a melody threading through the chatter of languages—Swedish—Arabic—Irish—as the Titanic sailed westward under a clear sky. When the ship hit the iceberg—their owners too rushed—or barred from lifeboats by locked gates—to save them—their wings beating against wire in vain as water loomed.

As water surged through the lower decks—the birds had no escape—some cages tipped over—spilling seed onto flooded floors—others floated briefly before sinking—their feathers sodden as the sea roared in—silencing their songs with a cold rush. A few survivors recalled hearing trills amid the panic—per newspaper reports after the rescue—The New York Times noted a Lebanese woman’s lament for her finch—its cage lost to G Deck’s deluge as her family vanished too. For these families—losing their birds was another blow—an unnoticed wound in a night that took everything else—husbands and children slipping into the dark with over 1,500 others. The canaries—once symbols of hope with their golden notes—became silent casualties—their fragile lives snuffed out in the Titanic’s descent—a poignant reminder of small joys swept away with the dreams of those who’d cradled them across an ocean’s breadth.

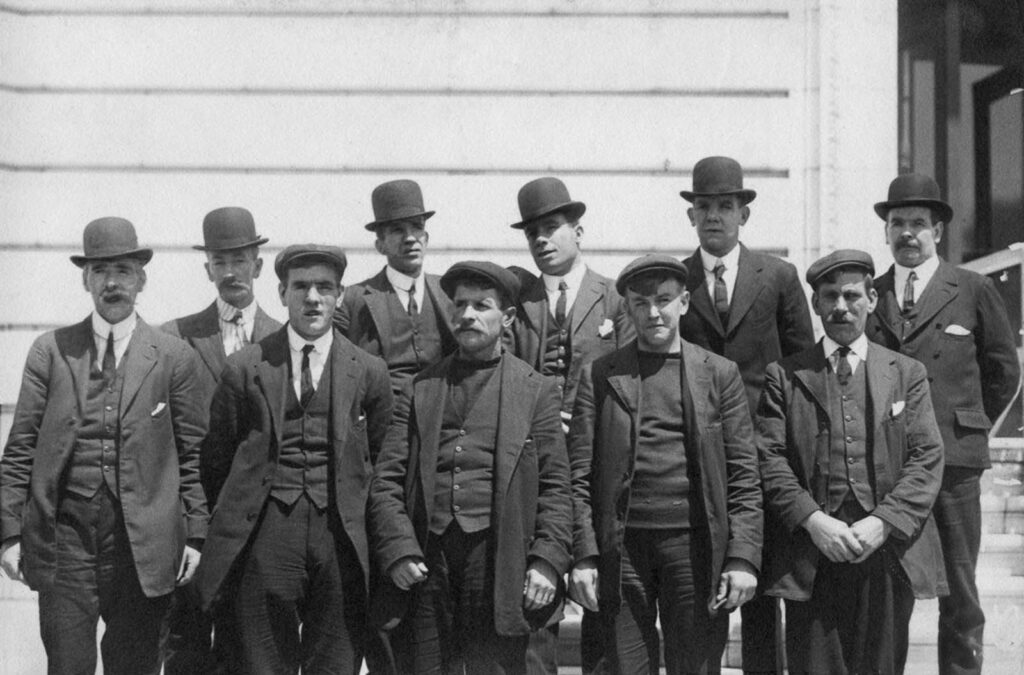

23. The Crew’s View: Animals in the Chaos

The Titanic’s crew—stewards—firemen—officers—knew the animals better than most—their daily rounds entwined with the ship’s menagerie from bow to stern. John Hutchinson—a carpenter—tended the kennel dogs on F Deck—walking them daily under the crisp April sun—Great Danes and Terriers stretching their legs as their barks mingled with the sea breeze—feeding them scraps of beef from the galley—his calloused hands gentle with each pat. Violet Jessop watched Jenny the cat hunt rats—her tabby tail flicking as she prowled the corridors—while stewards in steerage glimpsed third-class pets—kittens or birds—hidden in bags—their owners’ secrets shared with a nod. When the iceberg hit at 11:40 p.m.—these crew members faced their own scramble—lowering lifeboats—guiding passengers—but the animals lingered in their duties—a secondary concern as the ship tilted starboard under a moonless sky.

Hutchinson may have unlocked the kennel—survivors hinted decades later—his boots sloshing through rising water as dogs bolted up staircases—their howls lost in the din of creaking steel and shouting voices that filled the night. Stewards saw third-class birds and cats left behind as they herded people upward—powerless to help as cages tipped and mews faded—while officers on deck turned away pets like Frou-Frou—enforcing “humans only” rules over desperate pleas—as per inquiry records from the British Wreck Commissioner. The crew’s accounts show they noticed the animals’ fates—barks fading into the dark—cages sinking below—yet survival trumped sentiment—their hands too full with davits and ropes to save the creatures they’d fed and patted. Their view reveals a cold reality—animals—even those they’d grown fond of—were footnotes in a night ruled by human desperation—their loyalty drowned in the flood that spared fewer than half aboard.

24. Survivor Guilt: The Pain of Leaving Pets Behind

For survivors like Helen Bishop and Billy Carter—escaping the Titanic wasn’t a full victory—the pets they left behind haunted them—their absence a wound that festered beyond rescue into the gray dawn. Helen wept in her lifeboat—Frou-Frou’s paws tugging at her dress burned into her memory—a moment she relived in interviews after rescue—her voice breaking as she told The New York Times of his trembling form fading on the deck as Lifeboat 7 swung away. Billy—just a boy—sobbed for his Airedale Terrier—knowing it drowned in the kennel as his family rowed away in Lifeboat 4—his small hands clenched against the cold wood of the gunwale. These losses cut deep—pets weren’t just possessions—they were family—their barks and cuddles woven into daily life—and abandoning them left scars that lingered as the Carpathia steamed toward New York under a heavy sky.

On the Carpathia—survivors whispered of dogs barking as the ship sank—Great Danes and Spaniels howling from the tilting bow—a sound that echoed in their dreams—a chorus of guilt that weighed heavier than their soaked coats as dawn broke over the rescue. Some—like Margaret Hays—clung to their saved pets—Lady’s warmth a comfort amid the ache—while others faced empty hands and heavy hearts—their minds replaying the moment they turned away—Helen’s sobs mingling with Billy’s whimpers under a graying sky. The guilt wasn’t just personal—it was a shared burden among those who’d chosen life over loyalty—survivors huddled on rescue decks—shivering as the barks haunted them—Titanic Voices later captured their anguish—a testament to bonds broken by necessity. For them—and countless others—the Titanic’s toll wasn’t measured only in lives lost but in the pets left behind—a pain that followed them ashore—etched in memories of fur and feathers lost to the sea.

25. The Dog Show That Never Was: A Celebration Cut Short

The Titanic’s first-class passengers had big plans for their dogs—a dog show scheduled for April 15, 1912—to showcase their pedigreed pets—a gala event buzzed about in the saloon over cigars and claret as the ship sailed west. Owners like William Carter—with his Airedale Terrier and King Charles Spaniel—and Anna Isham—with her Great Dane—looked forward to parading their animals on deck—their coats brushed to a sheen for the occasion under the spring sun. The kennel on F Deck—stocked with breeds like Newfoundlands and Spaniels—was buzzing with anticipation—crewman John Hutchinson prepping the dogs with extra biscuits—their tails wagging as passengers swapped tales of past ribbons won in London or New York. It was set to be a highlight of the voyage—a display of wealth and pride—until the iceberg struck the night before—turning festivity into desperation as the ship shuddered at 11:40 p.m.—its steel groaning under the impact.

No ribbons were awarded that morning—instead—the kennel became a death trap—its steel cages rattling as water surged through F Deck—drowning the dogs before dawn broke over the wreckage—their howls silenced by the flood. The show’s cancellation marked a cruel pivot from luxury to loss—hours earlier—passengers like Carter laughed over their pets’ tricks in the smoking room—now—those same animals were sinking—a grim coda to the event that never was—survivors later told historians of the shift—as noted in Titanic Historical Studies—Anna Isham’s refusal to leave her Dane a stark echo of the day that might have been. It’s a stark reminder of how close normalcy sat to tragedy—the dogs’ fates sealed by a disaster that cared nothing for plans—or the pride of their owners—a celebration drowned in a night of splintered wood and icy waves that claimed over 1,500 souls—leaving only silence where barks once rang.

26. Panic on Deck: Animals in the Final Moments

As the Titanic tilted after midnight on April 15—the deck became a scene of chaos—humans shoving for lifeboats—and animals running free—their paws slipping on the slanting wood as the ship groaned under the strain of its breaking spine. Dogs from the kennel—Great Danes—Terriers—bolted up stairwells after someone unlocked their cages—their barks sharp against the night—cutting through the shouts of officers barking orders over the din of creaking steel. Passengers stumbled over them—some trying to grab their pets—William Carter reaching for his Airedale’s collar—others too panicked to notice as ropes snapped and lifeboats swung wildly. Anna Isham stood with her Great Dane—a still figure amid the frenzy—while Helen Bishop’s Frou-Frou slipped from her grasp—survivors later described the sight to reporters after rescue—a tableau of desperation under flickering lights that blinked against the dark.

The noise was unbearable—human screams—ship groans—and animal cries blending into a desperate roar as the bow dipped lower—water lapping at the rails—swallowing the deck in a cold rush. Smaller pets—like third-class birds—stayed trapped below—their cages sinking in steerage’s gloom—but the freed dogs raced across the deck—some leaping into the sea as the ship broke apart at 2:20 a.m.—their paws churning briefly before the 28-degree cold seized them—Great Danes paddling beside wreckage—Terriers lost in the waves. No lifeboat took them—the crew’s focus was human lives—leaving the animals to fate—a brutal end to a scramble where loyalty met abandonment. The deck was their last frantic stage—a vivid snapshot of a night that spared so little—etched in the memories of those who rowed away—hearing the fading howls as the lights died and the sea claimed its toll.

27. The Emotional Buildup: Pets Before the Sinking

Before disaster struck—the Titanic’s animals were part of its daily rhythm—first-class passengers like Margaret Hays strolled with Lady—her Pomeranian nipping at heels on the promenade—its bell tinkling against the sea breeze as ladies in hats nodded approval. William Carter’s son Billy visited his Airedale Terrier in the kennel—tossing it bits of bread from the breakfast tray—his laughter ringing as the dog bounded in its cage—its muddy paws a memory of Philadelphia romps. Anna Isham’s Great Dane drew stares on deck—a gentle giant she’d pet between meals—its deep eyes meeting hers with quiet trust under the April sun. Third-class families kept birds singing in cages—a canary’s trill soothing a child’s seasickness—the ship humming with life as dogs barked and cats prowled—each pet a thread in the voyage’s fabric—a comfort as the Atlantic stretched ahead.

Crew members played their part too—John Hutchinson tending the kennel—his rough hands doling out scraps to wagging tails—Great Danes and Spaniels nuzzling his apron—while Violet Jessop tossed fish to Jenny the cat—her purrs a soft note in the galley’s clatter amid the clink of pots. Passengers planned the April 15 dog show—chatting over breeds and prizes in the smoking room—Carter boasting of his Airedale’s fetch—Isham praising her Dane’s stature—a buzz that filled the days—as per passenger logs later studied—dreams of ribbons swapped over brandy and cigar smoke. No one foresaw the end—pets were a joy—a distraction—their presence softening the journey’s edges with wagging tails and chirps across decks and holds. That innocence—shared by humans and animals alike—made the night of April 14 all the more shattering—a sudden rip from routine to ruin—the bonds of those carefree days torn apart as the iceberg loomed—leaving only echoes of what had been.

28. The Speddens’ Terrier: A Child’s Companion Lost

Frederic and Daisy Spedden—a wealthy New York couple—boarded the Titanic with their six-year-old son Douglas and a small terrier—a pet that brought joy to their first-class journey—its wiry fur a constant in their C Deck suite amid trunks of fine linens. Douglas—an only child—doted on the dog—likely a Fox Terrier given the breed’s popularity among the elite—playing fetch with it in their cabin or tugging its ears on deck under Daisy’s watchful eye—his giggles a bright note against the ship’s hum. The Speddens were no strangers to luxury travel—the terrier had scampered through European hotels from Paris to London—and it fit their lifestyle—a lively companion kept close rather than kenneled below. On April 14—when the iceberg struck—the family rushed to Lifeboat 3—Douglas in tow—but the terrier’s size and the chaos meant it stayed behind—a detail Daisy later mourned in family letters—her pen trembling as she wrote of her son’s loss.

The Speddens survived—pulled aboard the Carpathia—but the terrier didn’t—likely trapped in their cabin as water flooded C Deck—its barks fading under the roar of the sea—or lost in the panic—unable to join the lifeboat as it swung away—leaving Douglas staring back at the sinking ship. His grief was palpable—he’d lost his playmate—a companion who’d tumbled with him on plush rugs—a loss Daisy noted in her writings after the rescue—The New York Times quoted her sorrow as “a child’s silent wound” against the night’s toll of over 1,500 lives. The terrier’s fate mirrored so many others—left behind despite its owners’ prominence—its absence a stark void as the family watched the Titanic vanish under a starless sky. For the Speddens—it was a small but sharp pain—a lively friend drowned in a night that spared their lives but not the pet who’d been Douglas’ shadow across an ocean’s breadth—a memory etched in a boy’s quiet tears.

29. Thomas Andrews’ Rumored Dog: Designer’s Companion?

Thomas Andrews—the Titanic’s brilliant designer—boarded as a first-class passenger to oversee his creation’s maiden voyage—a task that kept him busy inspecting every detail—rivets—railings—the sweep of the grand staircase—his notebook always in hand as he paced the decks. Among the whispers about him is a rumor of a dog—possibly a gift for his wife—Helen—back in Belfast—perhaps a wiry terrier or a collie—its presence hinted at in family lore as a surprise for their daughter—Elizabeth—to romp with on their lawn. No passenger list confirms it—and his A Deck cabin showed no signs of a pet when searched later—just blueprints and a half-drunk tea—but the idea fits his gentle nature—a man who’d pause to sketch a child’s smile. Andrews was last seen in the smoking room as the ship sank—calm amid the chaos—tossing chairs into the sea—a silent figure in a tuxedo—with no mention of a dog by his side.

If the dog existed—it didn’t survive—Andrews himself went down with the ship—likely near the bridge as water swallowed his masterpiece at 2:20 a.m.—and no lifeboat carried a pet tied to him—the rumor unverified by survivors like Violet Jessop—who knew him well—her silence a weight against the tale. Family letters suggest he loved animals—a collie had bounded through their Belfast garden—yet his focus was the Titanic—not a companion—as per studies by Titanic historians—The Shipbuilder paints him as a man wedded to his work—his mind on steel and steam. The tale likely grew from his warmth—a myth to soften the loss of a man who’d dreamed of an unsinkable ship—its bark—if real—silenced by the sea that claimed its maker. It lingers as a shadow in his story—a designer’s friend lost to the same fate as his creation—a quiet mystery in a night of stark tragedies that drowned over 1,500 souls.

30. Widener’s Possible Lapdog: Elite Whispers

George Widener—a Philadelphia millionaire—sailed with his wife Eleanor and son Harry—a first-class family steeped in wealth and influence—their suite on C Deck a showcase of gilded luxury—from velvet drapes to silver candelabras that gleamed under electric lights. Among the whispers after the sinking was a tale of a lapdog—perhaps a Pomeranian or Spaniel—kept in their quarters—its yips a soft note amid the clink of crystal at dinner as George sipped claret—Eleanor adjusting her pearls nearby. No manifest lists it—but Widener’s status made a pet plausible—elite families often traveled with small dogs—his love for opulence extending to every detail—including a rumored fluffy companion curled on a cushion. On April 14—as the iceberg loomed—the Wideners were at dinner in the saloon—their dog—if real—likely tucked away in their cabin—its snores unheard as the ship steamed toward its fate.

George and Harry didn’t survive—they stayed behind as Eleanor boarded Lifeboat 4—her fur coat pulled tight—but no dog joined her—its absence a void as the boat rowed away—survivors from the boat—interviewed later—never mentioned a pet—per The Philadelphia Inquirer reports from April 18, 1912—their voices hushed as they recalled the night’s toll—over 1,500 gone. If it existed—the lapdog drowned in the suite’s plush confines as water surged through C Deck—its tiny paws lost amid the chaos—or ran loose when the ship tilted—slipping into the dark waves that swallowed the saloon’s grandeur. The Wideners’ wealth couldn’t save their men or their pet—a fleeting possibility in a disaster that spared only what could fit in a lifeboat’s narrow hull. It’s a whisper of loss—unconfirmed but fitting—a small tragedy beneath the night’s larger grief—a shadow in a family’s gilded tale.

31. Third-Class Struggles: Hidden Pets Below

Third-class passengers—immigrants like the Sage family or Lebanese traveler Nassef Cassem—crowded steerage with little space—yet some brought pets—their trunks and bags alive with secrets beyond the manifest’s dry ink—small dogs with scruffy coats—cats with matted fur—or canaries in wire cages nestled among meager belongings. The Sages—all eleven of them—might’ve had a kitten purring in a burlap sack—its green eyes peeking out as children giggled—while Nassef—a merchant—could’ve carried a bird—its trills a memory of Levantine markets threading through steerage’s hum. These animals stayed secret—their owners dodging rules in the dim—creaking quarters below—where the air was thick with coal dust and hope—a mutt’s wag or a finch’s song a lifeline as the Titanic sailed west under a vast sky. They were humble treasures—kept close in a world where luxury was a distant gleam above.

When the Titanic sank—water flooded G Deck first—these pets had no chance—its icy surge trapping them as gates locked third-class passengers below—their faint barks or chirps echoing through the din—survivors like Ellen Shine later told of hearing them—as mentioned in historical accounts—a sound drowned by the flood that claimed over 1,500 lives. Lifeboats were out of reach—families like the Sages perished entire—eleven souls gone—their kitten with them—Nassef’s bird sinking in its cage—drowned unnoticed as the privileged rowed away under a starless sky. Unlike first-class dogs with kennels or cabins—these hidden companions faded—a silent loss in a disaster that favored wealth over want—their owners’ hands too full—or too weak against steel—to save them. Their stories are shadows—pieced from what little steerage survivors recalled—a testament to love persisting in the ship’s meanest corners—lost to the night’s relentless tide.

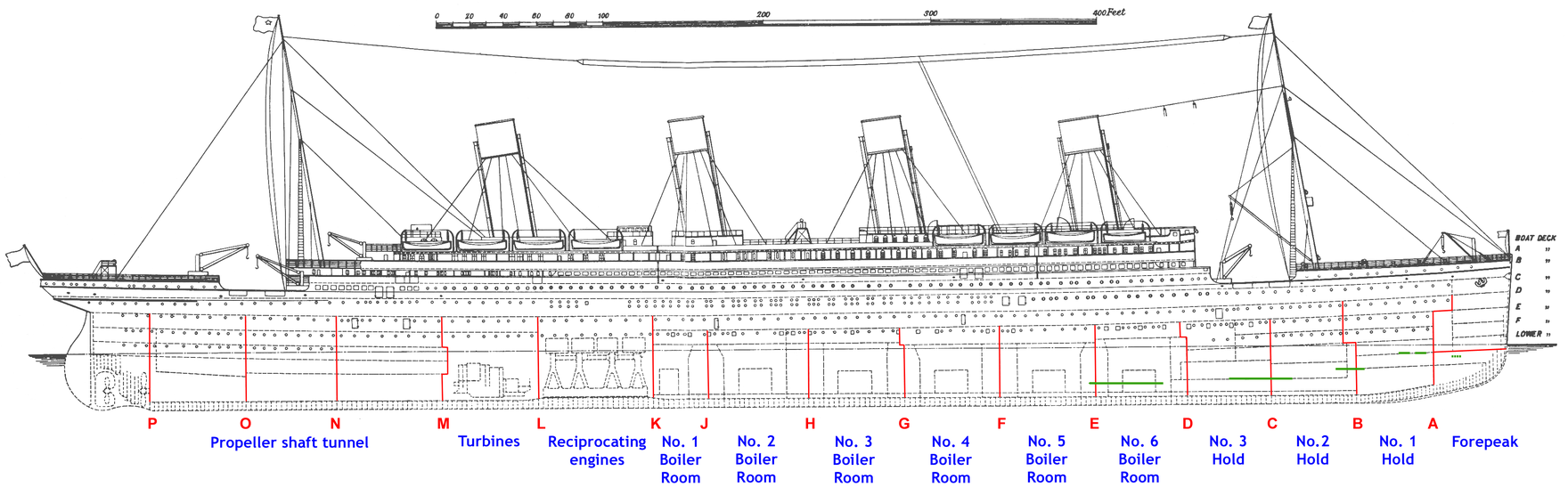

32. The Kennel’s Design: A Space Doomed by Location

The Titanic’s kennel sat on F Deck—starboard side—a modern setup for its time—with metal cages and wooden floors for up to a dozen dogs—its ventilated walls a nod to comfort over the boiler rooms’ heat nearby—where the ship’s pulse thrummed loud. Crewman John Hutchinson managed it—feeding Great Danes—Airedales—and Spaniels scraps of mutton—walking them daily on the poop deck—their barks mingling with the sea breeze as first-class owners like William Carter visited—admiring their glossy coats under the April sun. It was built for care—not safety—low in the ship—near cargo holds stacked with trunks and barrels—a detail ship blueprints confirm from Harland & Wolff’s meticulous plans—its dogs a pampered pack meant to last the voyage. The kennel was sturdy—a haven of biscuits and wagging tails—until April 14 proved its fatal flaw with a grinding crash at 11:40 p.m.—the iceberg’s edge slicing through steel below.

When the iceberg hit—F Deck flooded fast—water surged through bulkheads—reaching the kennel within minutes—its icy roar bending steel bars as the dogs howled—their cages a trap as the ship listed starboard. Hutchinson might’ve unlocked them—survivors speculated—his hands fumbling in the dark as lanterns swung—but escape was impossible—stairwells led up to chaos—and lifeboats were human-only—leaving the dogs to drown or run in vain as water climbed—Great Danes thrashing—Airedales sinking. The design failed them—too low—too enclosed—as per studies of Titanic’s layout by maritime historians—its ventilation no match for the sea’s rush that claimed over 1,500 lives. Dogs paddled briefly—or sank in their kennel tomb—a cruel irony for a space built for care—its location sealing their fate when the unsinkable ship met its match—a disaster that turned a haven into a watery grave by dawn on April 15—silencing barks with a cold—final hush.

33. Murdoch’s Role?: The Officer and Rigel Rumors

First Officer William Murdoch stood at the Titanic’s helm on April 14, 1912—when the iceberg loomed—a seasoned officer who’d served on White Star ships for years—his steady gaze scanning the horizon as the ship steamed at 22 knots through the night’s chill. After the sinking—a tale emerged tying him to Rigel—a Newfoundland dog said to have swum through icy water—barking to lead the Carpathia to a lifeboat—his deep woofs a lifeline in the dark—a story that spread in The New York World weeks later—painting him as Rigel’s owner—releasing him from the kennel or bridge before the ship sank. It’s a heroic image—Murdoch calm amid the panic of lowering boats—his cap firm as he shouted orders—yet he died that night—shot himself or drowned—accounts conflict—leaving Rigel’s link to him a fragile thread—unconfirmed by any log or witness in the chaos.

If Rigel existed—he’d have been a large dog—perhaps kenneled on F Deck—his thick fur a shield against the cold—or kept near the officers’ quarters—yet no survivor saw a Newfoundland amid the splintered decks—or heard his barks over the lifeboat scramble—Murdoch too busy lowering Lifeboat 1—his last act—to tend a pet. Historians—per the British Inquiry Report of 1912—call Rigel a myth—born from grief and a need for heroes—a tale too neat for the night’s mess of screams—waves—and over 1,500 lost lives. His real role was grim—he saved lives with ropes and orders—not a dog—his fate sealed as the ship tilted at 2:20 a.m.—a shadow cast over an officer’s final—frantic hours—Rigel’s barks—if they rang at all—silenced by the sea that took his supposed master—leaving only a rumor to echo through the years.

34. Media Myths: How Stories Grew After

The Titanic’s sinking gripped the world—and newspapers churned out tales—some true—some stretched—about its animals—their stories a balm for a public reeling from the loss of over 1,500 souls in the North Atlantic’s icy grip. Rigel the Newfoundland splashed across pages—a supposed hero barking through the night—his thick fur and booming voice a lifeline—a yarn The New York World ran in late April 1912—selling stacks to readers hungry for hope amid the wreckage’s grim tally. Edith Rosenbaum’s piglet—toy or real—became a quirky legend—her own words to reporters fueling the mix-up—her flair turning a mechanical trinket into a squealing survivor as headlines bloomed. These myths grew fast—readers craved light in the horror—and animals offered it—their stories twisting with each retelling into something larger than life—a flicker against the dark sea’s silence.

Truth blurred in the rush—no passenger list or survivor account confirms Rigel—his barks a fiction against the silence of drowned kennels—and Edith clarified her pig was mechanical—yet the tales stuck—as per studies of press coverage by Titanic Historical Studies—ink outpacing fact in the scramble for sales. Other pets—Frou-Frou—Lady—got brief mentions—but the wilder stories stole the spotlight—papers didn’t fact-check—they fed a hunger for marvels—printing headlines over breakfast tables from London to New York—Rigel’s swim—a piglet’s squeal—crafted to soothe a world’s grief. The animals’ real fates—drowned—saved—lost—faded behind the ink—leaving a legacy of half-truths that painted hope where there was none—a need to find heroes and whimsy in a tragedy that offered little—its echoes lingering in yellowed pages long after the sea settled over the wreck.

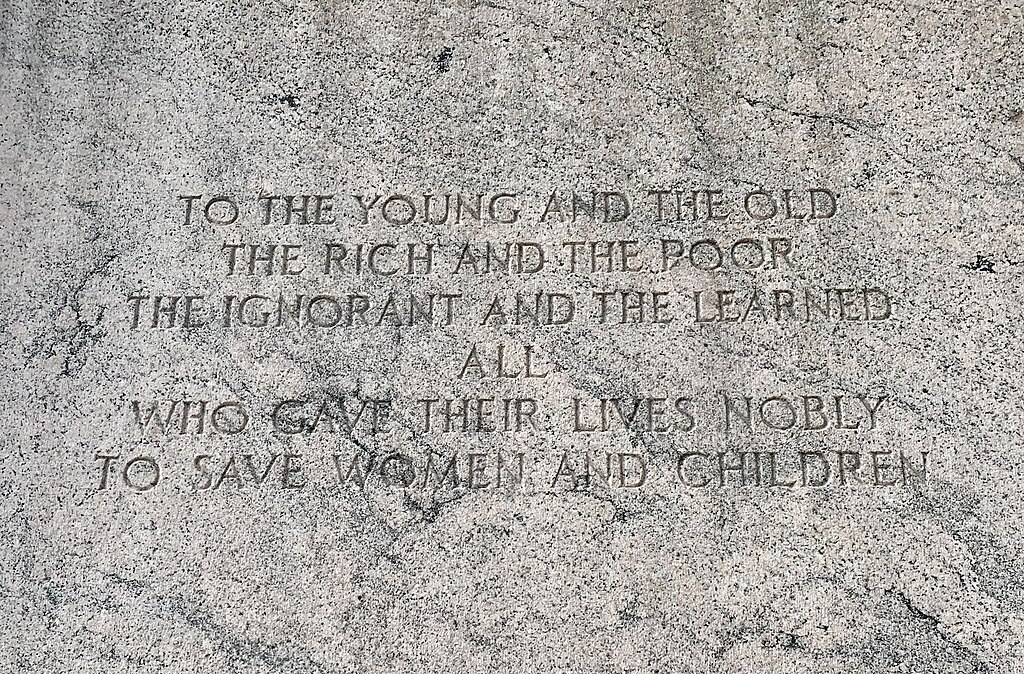

35. Legacy in Memorials: Remembering the Animals

Today—the Titanic’s animals live on in quiet corners—museums—books—and exhibits that honor their forgotten stories—a century after the ship’s steel husk settled into the Atlantic’s depths—2½ miles below the waves. The Titanic Museum in Pigeon Forge—Tennessee—displays relics of Lady—Sun Yat-Sen—and the kennel dogs—faded photos—a worn collar—survivor tales etched on plaques—drawing hushed crowds who linger over the trio that defied the odds of April 15, 1912. Books like The Lost Pets of the Titanic dig into Frou-Frou and Anna Isham’s Great Dane—pulling their fates from obscurity with ink and memory—their pages a tribute to the bonds that sank with over 1,500 lives. These efforts began decades after—a shift noted in modern Titanic studies—giving voice to the barks and chirps lost in the night—reclaiming their place in a tale too long human-bound.

No grand statues mark their loss—human memorials dominate—bronze figures of captains and widows tower—but small plaques and pages keep them alive—a subtle nod to the paws and feathers that shared the voyage from Southampton to doom. Visitors pause at the museum—moved by the three survivors—and the dozens lost—Billy Carter’s Airedale—Helen Bishop’s Frou-Frou—whose stories whisper through glass cases—their loyalty etched in the artifacts’ silence under soft lights. The legacy isn’t loud—it’s a murmur of devotion and grief—preserved in ink and memory for those who loved them—over a century later—finally mourned alongside the Titanic’s human toll. For the Bishops—Carters—and countless others—these animals were family—not mere cargo—their barks—chirps—and purrs a thread in a tragedy too vast—now honored in quiet corners where history bends to hear their echo—a testament to lives too small for headlines but too dear to fade.

36. A Shared Tragedy: Animals as Kin

The Titanic’s animals weren’t mere cargo—they were kin to those aboard—their lives woven into human hearts with threads of trust and tenderness that stretched across classes and decks—from polished suites to steerage’s gloom. Margaret Hays held Lady like a child—her Pomeranian’s warmth a shield against the night’s terror as Lifeboat 7 swung—Helen Bishop mourned Frou-Frou as a lost friend—his tug at her dress a ghost in her dreams as she rowed away. Anna Isham died with her Great Dane rather than leave him—their bond a fortress against the flood—while William Carter’s son Billy cried for his Airedale—its bark a memory of Philadelphia summers—a tie as real as any family bond—third-class birds sang for immigrants seeking hope—ship cats like Jenny worked beside crew—their presence a lifeline until the end came on April 15—1912—a night that tested loyalty and found it steadfast amid over 1,500 lost lives.

That night—the tragedy was shared—humans and animals faced the same cold—the same panic—their fates entwined as the ship split and sank beneath a starless sky—Isham’s Dane beside her—Frou-Frou’s bell silenced—survivors carried guilt—their pets’ cries echoing in memory—Billy’s sobs on the Carpathia—Helen’s whispers of paws—haunting them as vividly as the human wails—as noted in interviews decades later by The Titanic Commutator. The Titanic’s story is human—yes—but it’s animal too—a tale of devotion stretched to breaking—of small lives caught in a giant disaster that drowned dozens of creatures who trusted their owners to the last—their fur—feathers—and bonds shining through the wreckage. It’s a reminder that love—even for a pet—held weight in a night that spared so little—a chord of loyalty resounding in the silence—a testament to the kin who shared the dark with those they’d never leave behind.

Echoes of Loyalty—What’s Your Take?

The Titanic’s animals—pets—workers—companions—shared its fate—their stories of devotion and loss now unearthed from the shadows of history—a century after the ship’s steel heart sank. From Lady’s survival to Frou-Frou.