Some birds build homes that could rival Frank Lloyd Wright. Others? They’re like tiny Bauhaus pioneers with beaks. From silk-spun masterpieces to cliffside megastructures and nests that sway like chandeliers, animals across the globe are crafting some of the most inventive and jaw-dropping dwellings on Earth. These aren’t just places to crash, they’re engineering marvels with thermal regulation, predator-proofing, and aesthetics that would make a minimalist weep.

And it’s not just birds. Insects, mammals, and even fish are getting in on the design game, using mud, silk, spit, fur, feathers, and sometimes trash to build shelters that are wild in all the right ways. So forget real estate envy, these 21 animal architects deserve blue ribbons, gold medals, and maybe even their own Netflix show. Let’s tour the wildest, weirdest, and most award-worthy nests in the natural world.

1. The Sociable Weaver (Namibia)

In the arid reaches of southern Africa, sociable weavers have built what might be the most impressive animal co-op on Earth. These small, dusty-brown birds weave sprawling communal nests that resemble haystacks wedged into the forked branches of acacia trees. But inside, it’s a marvel of natural engineering: the structure houses up to 500 birds across multiple generations in separate chambers, with thick thatch providing insulation from both sweltering heat and freezing desert nights. Each chamber has its own entrance, and the design maintains internal temperatures up to 30°F cooler than the outside air in midday heat.

Some nests have lasted over a century, constantly added to and reinforced by new birds who inherit the structure. Even non-weaver species like pygmy falcons and lovebirds take up residence, making the nest a multigenerational, multi-species hub. The design is so effective that the outer thatch can be nearly a foot thick and even repels snakes and large predators. It’s desert architecture at its best: sustainable, social, and sturdy enough to outlive its makers.

Source: National Geographic – Sociable Weavers

2. Edible-Nest Swiftlet (Southeast Asia)

The edible-nest swiftlet spins its nest from nothing but hardened spit. Nesting in the echoing darkness of limestone caves in Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia, this tiny bird crafts a crescent-shaped cup entirely from its salivary strands. These nests adhere to sheer cave walls and shimmer like porcelain when caught in the beam of a flashlight. Each one takes 30 to 40 days to construct and is so prized in traditional Chinese medicine and cuisine that it can sell for thousands of dollars per pound, making them some of the most expensive animal products on Earth.

Traditionally harvested by climbers scaling bamboo poles in precarious conditions, modern conservation efforts have led to “swiftlet hotels”, darkened, humid structures built to mimic cave conditions and reduce pressure on wild populations. In the wild, these birds build up to three nests a year, each supporting one or two chicks. It’s a feat of minimalist architecture and biological ingenuity, entirely natural, gravity-defying, and strong enough to cradle life in the dampest, darkest corners of the world. Source: Audubon Society – Edible-Nest Swiftlet

3. Bowerbird (Australia and New Guinea)

The male bowerbird is the Casanova of the forest floor, armed not with color or song, but with impeccable interior design. These birds build bowers, not nests, as elaborate courtship displays: two vertical walls of sticks forming an avenue flanked by curated collections of brightly colored items. Each bower is decorated obsessively with everything from shells and flowers to stolen bottle caps, sorted by shade. Some species, like the satin bowerbird, show a distinct preference for blue, crafting what amounts to a monochrome installation worthy of a contemporary art gallery.

The bower is not used for nesting but solely for attracting a mate. Females visit multiple sites, judging males not by feathers or calls but by the symmetry and flair of their construction. In a particularly brilliant twist, some males use forced perspective, placing smaller objects closer to the entrance to make their bower look larger. It’s proof that the drive to create beautiful things isn’t uniquely human, and that in the animal kingdom, good design really can get you the girl. Source: BBC Earth – The Art of the Bowerbird

4. Cliff Swallow (North and South America)

Cliff swallows are the ultimate mud masons. Found across North and South America, these birds build gourd-shaped nests entirely out of mud, each one requiring up to 1,200 beak-sized pellets collected from puddles and riverbanks. They plaster these nests tightly together on cliffs or under man-made overpasses, forming colonies of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of homes. The finished nest features a narrow tubular entrance leading to a rounded chamber, protecting chicks from the elements and predators.

The colonies are loud and bustling, with swallows communicating through complex vocalizations as they ferry insects back to their chicks. Their nest-building efforts are highly synchronized; one bird’s construction often encourages others to build nearby. Over time, the structures become so dense that they resemble mini mud cities, with each nest contributing to collective thermal insulation and security. It’s efficient, enduring, and built one beakful at a time. Source: Cornell Lab of Ornithology – Cliff Swallow Nesting Habits

5. Termite (Africa and Australia)

From the savannas of Africa to the dry scrub of northern Australia, termite mounds rise like stone monuments, some as tall as 15 feet. These towering structures, made from soil, saliva, and dung, are the visible tips of underground megacities that house millions of termites. Inside the mound lies a labyrinth of tunnels, chimneys, fungus farms, nurseries, and royal chambers. Compass termites even orient their mounds north to south to regulate sun exposure, effectively creating solar-powered climate control.

The internal temperatures of these mounds stay within a few degrees year-round, despite external conditions swinging by more than 60°F. Air flows passively through internal ducts, carbon dioxide is vented, and humidity is perfectly maintained for cultivating symbiotic fungi that feed the colony. Termites achieve all this without a blueprint, just instinct and cooperation. It’s one of nature’s most complex architectures, built by blind insects less than an inch long. Source: BBC Earth – Termite Architecture

6. Tailorbird (Asia)

The tailorbird doesn’t gather sticks or spin silk; it sews. Using its beak like a needle, it pierces the edges of a broad leaf and threads spider silk or plant fiber through the holes to “stitch” it into a hanging pouch. The bird selects naturally curling leaves to help hide the entrance, creating a nearly invisible cradle suspended in foliage. Once the outer casing is secure, it lines the inside with feathers, cotton, or soft plant fuzz to form a cozy, insulated nursery for its eggs.

This avian tailor works meticulously, returning again and again to reinforce stitches or add structural tweaks. Despite their tiny size, most are smaller than a sparrow, the strength and precision of their sewing rivals that of any hand-stitched garment. The finished nest not only camouflages perfectly among green leaves but also resists wind and rain. It’s a feat of design built from instinct and ingenuity, blending botanical scaffolding with organic thread. Source: Birds of the World – Tailorbird Nesting Behavior.

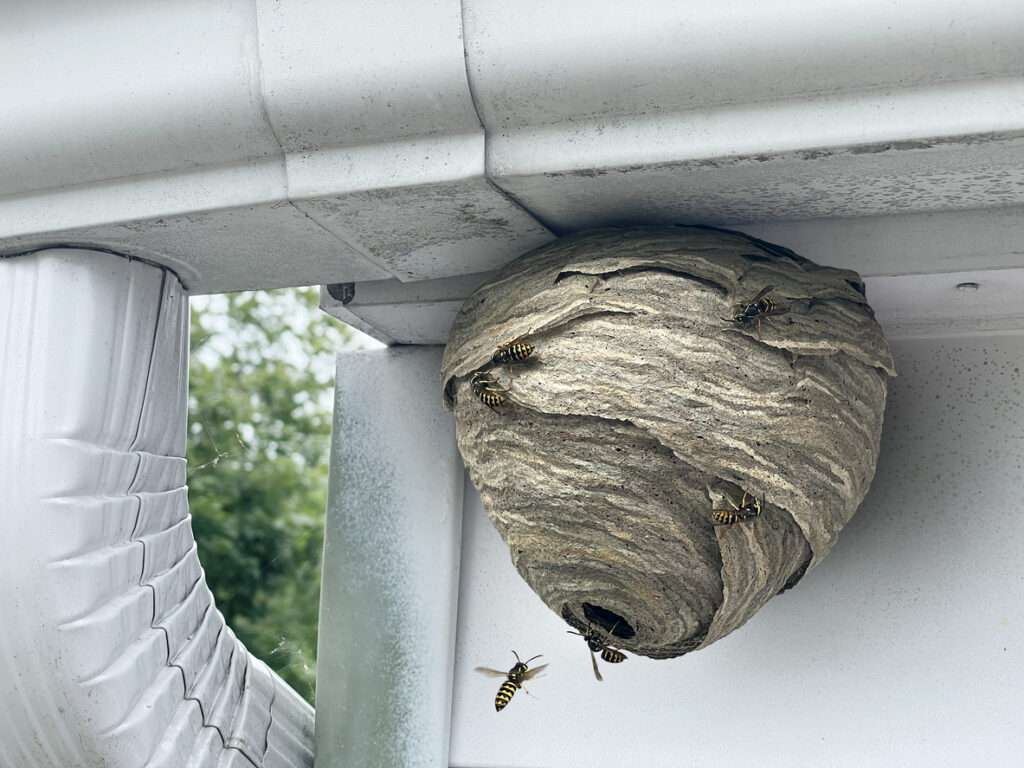

7. Paper Wasp (Worldwide)

Paper wasps are the origami engineers of the insect world. They chew wood fibers and mix them with saliva to form a paper-like pulp, which they mold into umbrella-shaped nests made of layered hexagonal cells. These open-faced structures hang from a single stalk under tree limbs, rock ledges, or roof eaves. Each nest is lightweight but incredibly strong, able to house dozens of larvae while withstanding weather and predators.

Inside, the nest operates like a miniature city. Workers fan their wings to control temperature, feed the young, and maintain the structure. Colonies expand the nest layer by layer as their numbers grow, and the cells are reused or cleaned out between broods. The geometry is flawless, perfect hexagons arranged for maximum efficiency, airflow, and insulation. While their sting earns them a fearsome rep, paper wasps are precise, sustainable builders whose designs rival the efficiency of modern prefab housing. Source: Entomology Today – Paper Wasp Nest Design.

8. Hamerkop (Sub-Saharan Africa)

The hamerkop is a compulsive builder with a flair for excess. These stork-like birds assemble enormous dome-shaped nests using over 10,000 twigs, some nests weigh more than 100 pounds and span over five feet across. Tucked into riverbanks, trees, or rock outcrops, the structure features a sealed entrance tunnel leading to a nesting chamber padded with mud, moss, and feathers. The walls are so thick and reinforced that even large predators like snakes and monitor lizards struggle to breach them.

Many hamerkops build more than one nest per year, some even build multiple just for practice or status. Their nests are so sturdy that owls, snakes, and other birds often move in once the hamerkops leave. In some areas, these giant stick fortresses have become symbols of good luck or even spiritual significance. It’s not just a shelter, it’s an architectural statement of obsession, strength, and wild creativity. Source: Audubon Society – Hamerkop Nest Architecture.

9. Oropendola (Central and South America)

Suspended like jungle chandeliers, the nests of the oropendola dangle from towering tropical trees in pendulous loops of braided grass and vine. Each nest can reach lengths of six feet, swaying dramatically in the breeze, far above the reach of snakes, monkeys, or climbing predators. These birds often nest in colonies with dozens or even hundreds of nests per tree, forming a sky-high village of green hammocks.

What makes these nests even more formidable is their partnership with nature. Oropendolas often nest near aggressive wasps, relying on their neighbors for added protection. The design allows for cool airflow, drainage during tropical storms, and even gentle rocking that soothes chicks. Each nest is crafted by the female over weeks, woven with strength and finesse. Hanging like natural mobiles, these suspended sanctuaries are part cradle, part fortress, all grace. Source: Cornell Lab of Ornithology – Oropendola Nesting Behavior.

10. Trapdoor Spider (Worldwide)

The trapdoor spider is an ambush predator with the skills of a stealth architect. It burrows a vertical tunnel in soft earth, lines the walls with silk, and creates a hinged “door” using dirt, moss, and more silk. The lid is camouflaged so perfectly that it vanishes into the landscape, lying flush with the ground. From beneath, the spider senses vibrations via silken tripwires and explodes out in a flash to seize unsuspecting prey.

These nests double as bunkers, resistant to rain, heat, and even minor floods. Some trapdoor spiders reinforce the tunnel walls with additional layers over time, making them stronger with age. Others dig side tunnels or bolt holes to escape predators. Each nest is solitary and painstakingly maintained, a fortress built from instinct, silk, and soil. It’s nature’s version of a camouflaged panic room, silent, strategic, and highly effective. Source: Australian Museum – Trapdoor Spider Nesting Habits.

11. Hornet (Worldwide)

Hornet nests are masterpieces of papery precision and climate control. Crafted from chewed plant fibers mixed with saliva, the nest appears as a swirled gray orb, layered like a mille-feuille pastry and suspended from trees, shrubs, or eaves. Inside, rows of hexagonal cells are stacked in tiers, each holding an egg, larva, or pupating hornet. Colonies can grow to several hundred individuals, with workers constantly fanning the structure to maintain stable internal temperatures.

The architecture is deceptively complex. The outer paper shell insulates the interior, and ventilation pathways keep the brood cool in summer heat. In some species, the queen starts construction solo, laying eggs and building cells, until the first brood of workers takes over. By season’s end, the entire colony may abandon the nest, which then degrades naturally. Despite their aggressive reputation, hornets are expert builders whose designs rival any multi-story condo, just with more stings. Source: National Wildlife Federation – Hornet Nest Structure.

12. Red Ovenbird (South America)

The red ovenbird, or rufous hornero, is famous for building homes that look like terracotta ovens perched on fenceposts and tree limbs. Using mud mixed with straw and dung, the birds carefully sculpt domed, earthen nests with a twisting interior tunnel that leads to a nesting chamber. Once dry, the structure becomes as solid as baked clay and resistant to both rain and heat. The result is an iconic silhouette dotting the South American countryside.

These birds are meticulous masons, working in pairs over two to three weeks to complete each home. Often, they reuse old nests year after year, patching and expanding them as needed. Abandoned nests are regularly adopted by other birds, reptiles, or even small mammals. In some countries, spotting an ovenbird nest is considered a sign of good fortune and hard work, a fitting tribute to its architectural tenacity. Source: Handbook of the Birds of the World – Rufous Hornero.

13. Harvest Mouse (Europe and Asia)

The harvest mouse builds one of the smallest and most enchanting nests in the animal kingdom. Using only its paws, teeth, and tail, this tiny rodent constructs a tight, grapefruit-sized ball of woven grass suspended between stalks of wheat or reeds. The nest is anchored to live plants, allowing it to flex with the wind and stay concealed high above the ground. Inside, the space is just large enough for the mother and her litter.

The mouse weaves living grass stems into the structure, which keeps the nest secure without detaching the host plants. This unique method allows the structure to grow with the environment and remain camouflaged against aerial predators. Nests are usually built three to four feet off the ground and are reused throughout the breeding season. It’s lightweight, weather-resistant, and impossibly delicate—like a handmade purse stitched right into the field.

Source: Mammal Society UK – Harvest Mouse Nesting.

14. Leafcutter Ant (Americas)

Below ground, leafcutter ants build vast cities by hand, well, mandible. These ants strip foliage not to eat, but to use as compost to grow a symbiotic fungus, their main food source. Their underground nests can stretch the size of a tennis court, with hundreds of chambers dedicated to specific functions: nurseries, gardens, dump sites, and even air vents to maintain ideal humidity and temperature.

Each colony can house millions of ants, all organized into castes with specific jobs. Workers excavate soil and carve smooth, curving tunnels that allow air to flow and waste to drain. Some chambers are deep underground to maintain cool temperatures, while others are raised for gas exchange. The entire system operates with logistical efficiency rivaling human infrastructure, an ant-built metropolis sustained by farming, waste management, and architectural precision. Source: Science Magazine – Leafcutter Ant Architecture.

15. Megapode (Australasia)

Forget brooding. The megapode lets nature do the work by building giant compost piles to incubate its eggs. These turkey-like birds rake together mounds of decaying leaves, soil, and debris, some over ten feet wide and three feet tall. The heat generated by microbial decomposition warms the buried eggs. Males use their beaks to monitor internal temperatures daily, adjusting the pile to keep it between 89–95°F, ideal for embryo development.

The process is so precise that some species add or remove material depending on rainfall or sunlight. Once hatched, chicks claw their way out unaided, fully feathered and capable of flight within hours. The entire structure functions as a self-regulating hatchery, with no parental care post-laying. It’s low-maintenance parenting powered by biology, geothermal energy, and some truly dedicated landscaping. Source: Australian Wildlife Conservancy – Megapode Strategies.

16. Wasp Spider (Europe and Asia)

The wasp spider might look fierce, but it’s a meticulous mother. After mating, the female spins a large, urn-shaped egg sac out of golden silk, suspending it in tall grass or shrubs. The sac, about the size of a marble, is tough and thick-walled to resist predators, parasites, and frost. Inside, hundreds of eggs are kept warm and secure through the winter, insulated by layered silk that regulates humidity and temperature.

Each female produces just one or two sacs in her lifetime, guarding them until the cold arrives. By spring, spiderlings burst free, scattering like confetti into the grass. The structure is so recognizable that it’s often used by biologists to locate breeding areas. Its unique shape and strength, part lantern, part vault, make it one of the most protective egg casings in the spider world. Source: British Arachnological Society – Wasp Spider Behavior.

17. Weaver Ant (Africa and Asia)

Weaver ants are the tree-top tailors of the insect world. These bright green ants create large, spherical nests by stitching living leaves together using silk produced by their larvae. Adult ants pull leaves into position, sometimes forming chains of ants to span the gap, and then hold them in place while others apply silk. The finished nest is lightweight, waterproof, and capable of swaying with the canopy.

One colony may build dozens of these nests across multiple trees, linked by trails of workers transporting food and brood. Each nest houses different castes, including guards stationed at entry points. These nests are more than shelter—they’re hubs in a complex, multi-nest network that forms a superorganism in the treetops. It’s collaborative construction, woven into the branches themselves. Source: Myrmecological News – Weaver Ant Nest Structure.

18. Flamingo (Africa, South America, Asia)

Flamingos build mud towers—one-foot-tall volcanic cones that rise from salty lake beds. The birds use their curved bills and feet to pile and shape the cones, adding moisture to help the mud stick. At the summit, they carve a shallow bowl just wide enough for a single egg. The elevation protects the egg from flooding, overheating, and aggressive neighbors in densely packed colonies.

A flamingo couple maintains the nest throughout the incubation period, adjusting the mud as needed. These nests dot alkaline flats like bizarre sculptures, hundreds or thousands of cones stretching as far as the eye can see. Despite their minimalist appearance, they’re thermally efficient, flood-resistant, and perfectly suited to some of the harshest, most toxic environments on Earth. Source: Smithsonian’s National Zoo – Flamingo Nesting

19. Kingfisher (Worldwide)

Rather than build above ground, kingfishers dig deep. They use their powerful bills to tunnel horizontally into sandy riverbanks, forming burrows up to six feet long. The tunnel ends in a chamber just large enough for a clutch of eggs, protected from sun, rain, and predators. The entrance is often nearly invisible, located just above the waterline or high on a vertical cliff.

The nest’s insulation is so efficient that temperatures inside remain remarkably stable. Many species add no lining at all—just a clean, dry chamber dug by determination. Some even use multiple burrows, abandoning one if disturbed. From the outside, it’s easy to miss, but inside, it’s a perfectly engineered riverbank retreat, carved by instinct and shaped by landscape. Source: British Trust for Ornithology – Kingfisher Nesting

20. Monk Parakeet (South America, Now Worldwide)

The monk parakeet is a parrot with a builder’s soul. Instead of nesting in tree hollows like other parrots, it constructs giant communal stick nests, massive tangled spheres that can weigh over 500 pounds. Each pair builds a separate chamber inside, with its own entrance tunnel. Over time, dozens of pairs may add to the nest, forming a multi-unit avian apartment complex.

These structures are often built on utility poles, trees, or even radio towers, any sturdy perch will do. Nests are reused and expanded for years, and birds often help repair one another’s chambers. Though considered pests in some regions, monk parakeets have earned admiration for their collaborative design and year-round residency. It’s one of the only parrots that builds its own home from scratch—and it does so with flair. Source: Cornell Lab – Monk Parakeet Nesting

21. Pufferfish (Japan)

Beneath the waves off southern Japan, the male white-spotted pufferfish carves intricate, mandala-like circles in the sandy seabed. These underwater nests, spanning up to seven feet in diameter, are built entirely with fin movements over 7–10 days. The ridges and furrows are perfectly spaced to minimize ocean currents and trap fine sand in the center, ideal for egg-laying.

If a female approves the design, she lays her eggs in the center while the male fertilizes and guards them. After the eggs hatch, the tide eventually erases the nest. The pufferfish starts again, sculpting another masterpiece. Researchers didn’t know who made these circles until 2012, and once discovered, they became known as one of the ocean’s most mind-blowing courtship structures. Source: Scientific American – Pufferfish Nesting

22. African Social Spider (Southern Africa)

Unlike most spiders that are fiercely solitary, the African social spider (Stegodyphus dumicola) lives in vast colonies, constructing enormous silken nests that sprawl over entire shrubs and small trees. These communal webs can measure several feet across, composed of layered silk tunnels that serve as shared shelters, nurseries, and ambush zones. Built in dry savannas, the nests are strengthened with sand and plant debris, giving them a thick, felted texture. Up to 2,000 spiders can live together in one silken metropolis.

Inside, roles are divided: some spiders hunt, others guard, and many help care for the young. Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of their society is cooperative parenting. Females share egg care, and in a macabre twist of devotion, some allow themselves to be eaten by spiderlings once they hatch, a behavior known as matriphagy. These silk-wrapped cities are a rare example of social living in arachnids, designed not just for survival, but for cooperation. Source: National Geographic – Social Spider Colonies.

23. White-Bellied Woodpecker (India & Southeast Asia)

Perched high in the canopy of ancient forests, the white-bellied woodpecker builds one of the deepest tree cavity nests in the avian world. Using its powerful chisel-like bill, it carves vertical burrows into the trunks of towering rainforest trees, sometimes excavating chambers up to three feet deep. The entrance is small and nearly invisible from the ground, making it a safe haven from predators like snakes or monkeys. The smooth interior walls are carved with precision, free of splinters or debris.

These nests are typically built in trees 60 to 100 feet tall, and the same cavity may be reused year after year, with maintenance performed before each breeding season. The isolation, elevation, and insulation make them ideal for humid tropical climates. Their remote location and architectural precision turn each cavity into a kind of high-rise condo for one of the most elusive woodpeckers in Asia. Source: BirdLife International – White-Bellied Woodpecker Profile

24. Compass Termite (Northern Australia)

Though termite mounds already made the list, the compass termite deserves its entry for sheer ingenuity. These termites build wedge-shaped mounds up to 10 feet tall, all precisely aligned north to south, like giant stone blades standing upright in the outback. This alignment minimizes exposure to the harshest sun angles, allowing one side of the mound to warm in the morning and the other to cool in the afternoon, helping to regulate internal temperatures throughout the day.

Inside, the mound contains a dense network of tunnels, nurseries, and fungus gardens, all kept at nearly constant temperature and humidity. The structure functions like a giant passive solar building, designed entirely through instinct. The shape also helps shed heavy rains during the wet season. With no formal architect and no tools, these termites have mastered climate-sensitive architecture that rivals human green design. Source: Australian Geographic – Compass Termite Mounds.

25. Long-Tailed Tit (Europe and Asia)

The long-tailed tit builds a nest that is equal parts shelter and snuggle pod. Shaped like a domed cocoon, the nest is constructed from spider silk, moss, and hundreds of flakes of lichen, meticulously stitched together and bound to tree branches or thorny shrubs. The entire outer surface is speckled in gray and green to match the bark, while the inside is lined with up to 2,000 feathers to cushion the eggs and insulate the chicks.

The nest is so elastic that it expands as chicks grow, stretching without tearing. Parents, and sometimes relatives, take turns maintaining the structure and feeding the young. Built low in hedgerows or thickets, it’s camouflaged against predators and durable enough to last through cold rains. The craftsmanship is so refined it rivals luxury bedding, nature’s answer to a down-filled sleeping bag, tucked in a mossy glove. Source: Royal Society for the Protection of Birds – Long-Tailed Tit Nesting.

Every one of these nests is more than just a shelter, it’s a solution. Built without blueprints, budgets, or backup plans, these structures prove that animals can be engineers, artists, and environmental designers in their own right. They balance aesthetics with survival, insulation with visibility, and vulnerability with protection—sometimes all in a single leaf, stick, or thread of silk.

So the next time you pass a wasp nest, a lump in the trees, or a strange pattern in the mud, look again. It might just be the work of one of the animal kingdom’s unsung architects. They don’t win prizes. But they deserve them.

If you liked this story, please give us a thumbs-up so we know to write more stories like this. If you didn’t like it, if we’ve missed anything, or if you would like to pitch your own story ideas to Fetch, please let us know in the comments or email Michael Gitter at mgitter@gmail.com.