1. Floppy or Pendulous Ears

The appearance of floppy or pendulous ears is a classic sign of domestication, seen in dogs, pigs, cattle, and rabbits, yet rarely in their wild relatives. This seemingly minor trait is a byproduct of the “domestication syndrome,” a collection of traits that often appear together when animals are selected for tameness. Floppy ears are believed to result from changes in the neural crest cell migration during embryonic development. This same cellular pathway also influences adrenaline production and craniofacial development. Since humans select for reduced fear and aggression (lower adrenaline), the physical trait of floppy ears comes along for the evolutionary ride, giving many domestic animals their characteristic softer, more ‘neotenic’ (juvenile-like) appearance.

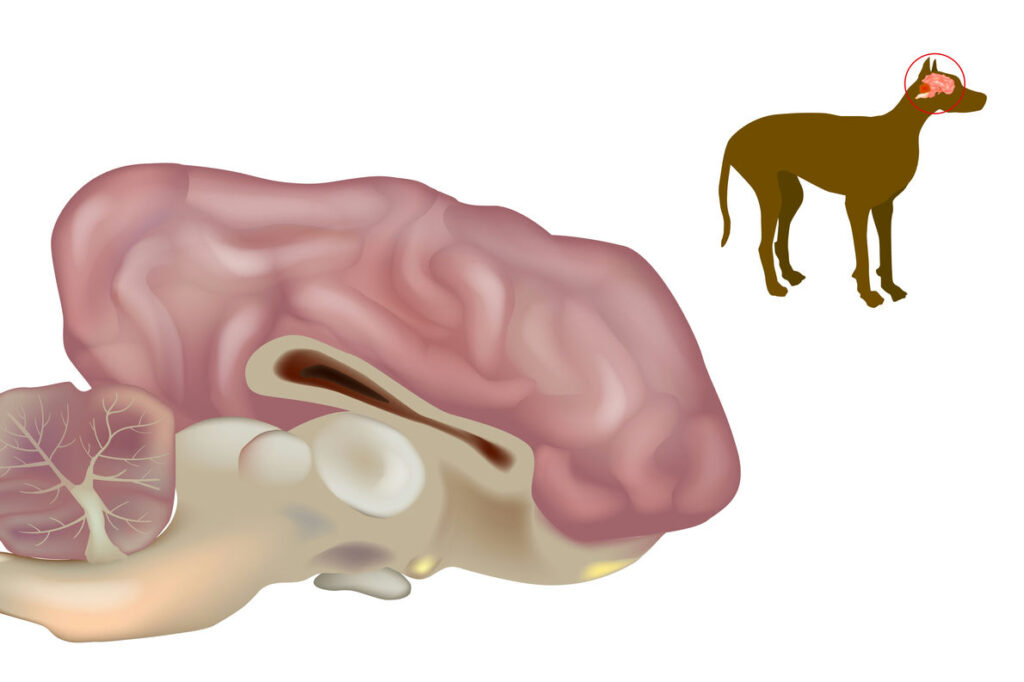

2. Reduced Brain Size

One of the most widespread and subtle adaptations in domesticated mammals, including pigs, sheep, dogs, and cats, is a reduction in brain size compared to their wild counterparts. This physiological change is strongly linked to the reduced need for complex survival skills like fear, aggression, and intricate hunting strategies in a human-controlled environment. For example, a domestic pig’s brain can be up to 34% smaller than a wild boar’s. The energy savings from a smaller brain can then be allocated to other functions, like faster growth or increased reproductive output, both beneficial traits for human use. This change reflects a trade-off where the sophisticated neurological structures for detecting and reacting to danger become less critical under human protection.

3. Shorter Muzzles and Dental Changes

In numerous domesticated species, especially dogs, pigs, and rabbits, there is a clear trend toward shorter muzzles, reduced skull length, and smaller, less crowded teeth. This is another key element of the domestication syndrome, thought to be related to changes in the structure of the skull due to selection for reduced aggression and a less carnivorous diet. The strong jaws and large canine teeth necessary for hunting or fierce defense in a wolf, for instance, are energetically costly and unnecessary for a domesticated dog fed prepared food. As a result, many modern dog breeds, like the Pug or Boxer, exhibit extreme forms of brachycephaly (shortened face), which would likely be detrimental to survival in the wild.

4. Piebald (Spotted) Coat Coloration

The patchy white and colored coat pattern, known as piebaldism, is a common feature in many domesticated animals, from cattle and horses to guinea pigs and chickens, but is extremely rare in wild populations. Like floppy ears, this distinct color pattern is thought to be a side effect of selecting for tameness. The white patches result from a failure of pigment cells (melanocytes), which also originate in the neural crest, to migrate properly across the skin’s surface during development. When breeders prioritize a calm temperament, they inadvertently select for the same genetic and developmental changes that cause a disrupted migration pathway, leading to the familiar spotted look.

5. Changes in the Breeding Cycle

Many domesticated species, particularly sheep, goats, and cattle, have evolved to become polyestrous, meaning they can breed multiple times a year, or even year-round, rather than following a strict, seasonal reproductive cycle (monoestrous) like their wild ancestors. This adaptation was directly selected for by humans to maximize food production, ensuring a steady supply of milk, meat, and new offspring. For example, domestic cows can cycle roughly every 21 days year-round, a massive reproductive advantage over the seasonal breeding of wild aurochs. This biological change allows farmers to better manage calving seasons and increases the overall productivity of their herds.

6. Extended Puppy- or Kitten-like Behavior (Neoteny)

Domestic animals often display neoteny, which is the retention of juvenile physical and behavioral traits into adulthood. This is most pronounced in dogs, which often exhibit behaviors like playful nips, social solicitation (licking), and a willingness to learn well past the age when a wolf would become fiercely independent and territorial. Humans have unconsciously or consciously selected for animals that retain the charming, dependent behaviors of youth, making them easier to train and live with. This prolonged ‘juvenile’ phase fosters a lifelong bond between the animal and its human caretaker, a crucial adaptation for life in a human-centric world.

7. Wool Production in Sheep

The thick, continuously growing fleece of modern domestic sheep is a remarkable adaptation absent in their wild ancestor, the Mouflon, which has a coat composed of stiff hair and a short, fine undercoat that sheds seasonally. Humans selectively bred sheep over thousands of years specifically for this dense, curly fiber that does not shed naturally. This means the animal must be shorn, a process that is entirely reliant on human intervention. This adaptation has been a boon for the textile industry, but it has made the domestic sheep wholly dependent on human care to prevent overheating and mobility issues from excessive wool growth.

8. Increased Milk Yield and Lactation Period

Modern dairy cows, such as the Holstein-Friesian, have been selectively bred to produce staggering quantities of milk, far exceeding what is necessary to feed a calf. A wild bovine female would lactate just long enough to sustain her calf until weaning, often producing only a few liters per day. In contrast, high-producing domestic dairy cows can yield over 40 liters of milk daily and maintain lactation for much of the year, even when not pregnant. This extreme physiological adaptation is a direct result of human artificial selection for genes that maximize mammary gland efficiency and extend the productive phase of their reproductive cycle.

9. The “Dwarf” and “Giant” Size Spectrum

Domestication has led to an incredible, and often rapid, divergence in body size within a single species, far exceeding the natural variation found in the wild. Consider the dog: a Chihuahua is dramatically smaller than its ancestor, the wolf, while a Great Dane or Irish Wolfhound is significantly larger. This wide spectrum of “dwarf” and “giant” breeds is due to human selection for specific aesthetic and functional traits. These size extremes often come with physiological trade-offs, making the animals highly dependent on human care, but perfectly suited for their intended domestic role, be it companionship or specific work tasks.

10. Fat-Tailed Sheep Breeds

A unique adaptation found in many domestic sheep breeds across the Middle East, North Africa, and Asia is the massive accumulation of fat in their tails or rump. Unlike the fat evenly distributed over the body in wild sheep, this localized storage serves as a vital energy and water reserve, similar to a camel’s hump. This trait was selectively bred by humans in arid regions because it provided a concentrated, high-quality cooking fat, offering superior long-term survival for the sheep during severe droughts while also benefiting human consumers with a durable, valuable food product.

11. Absence of Natural Seed Dispersal Mechanisms

In many domesticated grains, and by extension the livestock that consume them, there’s an adaptation that stops the spontaneous shattering of seeds (or seed heads) at maturity. Wild grasses and cereals shatter their seed heads to disperse their offspring. Conversely, domesticated crops, like corn and wheat, have a non-shattering rachis (the part that holds the seeds), a trait that humans explicitly selected for to make harvesting efficient. This adaptation means the plant, and its product, is now entirely dependent on humans for its survival and propagation, representing a profound co-evolutionary change that dictates the modern agricultural landscape.

12. Hairless or Fine-Coated Breeds

Many domestic animal species feature breeds with very fine, sparse, or entirely absent coats, a striking contrast to the thick fur or hair of their wild ancestors which is essential for protection and thermoregulation. Examples include the Sphynx cat, various hairless dog breeds (like the Chinese Crested), and the naked neck chicken. This adaptation is generally a result of human preference for novel aesthetics or for animals that are easier to keep indoors. Without their natural protective coat, these animals have a reduced tolerance to environmental extremes, highlighting their complete reliance on human-provided shelter and warmth.

13. Extreme Variety in Eye Color

While most wild mammals have a uniform brown or amber eye color, domestication has given rise to an incredible range of eye colors, most notably in dogs and horses, with blue eyes being a prominent example (like in Siberian Huskies). This change is often a genetic side effect of selecting for specific coat colors or patterns, as the genes controlling pigment in the iris are linked to those affecting the coat. In the wild, such variation is rare, suggesting that the selective pressure for camouflage and survival often restricts these aesthetically pleasing but otherwise neutral genetic anomalies.

14. Enhanced Affiliation and Human-Reading Skills

Domestic dogs possess a remarkable, genetically-encoded ability to read and respond to human social cues, an adaptation largely absent in their wolf ancestors. They can reliably follow a human’s point or gaze to find a hidden object, something even chimpanzees struggle with. This skill is a behavioral adaptation that evolved through selection for cooperative hunting and companionship. This enhanced affiliation allows for complex, mutual communication that forms the foundation of the human-dog bond, enabling dogs to thrive in diverse human work and companion roles.

15. Non-Seasonal Shedding (Minimal Coat Change)

Many modern dog and cat breeds have lost the ability to perform a complete, seasonal “blow-out” of their undercoat, a natural process essential for wild animals to adapt to changing temperatures. Breeds like the Poodle or Maltese, which are often described as “hypoallergenic,” shed very little or only fine hairs. This adaptation is advantageous for humans who prefer less hair in their homes, but it necessitates regular grooming and clipping by a human owner to prevent matting, a form of total dependence on human maintenance for hygiene and comfort.

16. Curled or Screwed Tails

The tendency for the tail to curl over the back or to be shortened and twisted into a “screwed” shape is a common morphological feature in domesticated animals, including pigs and numerous dog breeds like the Pug and Bulldog. The curled tail is thought to be an indirect consequence of the reduced fear and stress response associated with the domestication syndrome. Reduced tail-wagging, which is linked to lower adrenaline levels and a shift in muscle and ligament development, can result in the tail taking on a permanent, curled position, a feature that would likely inhibit a wild animal’s ability to use its tail for balance or communication.

17. Increased Egg-Laying Frequency

Modern domestic hens, particularly those bred for commercial egg production, have been selectively bred to lay eggs almost daily, year-round. Their wild ancestor, the Red Junglefowl, lays only a small clutch of eggs once or twice a year. This extreme physiological adaptation results in an output that is biologically unsustainable without the consistent, high-energy feed provided by humans. This trait has transformed the chicken into a biological factory, but it comes with a complete reliance on humans for nutrition and protection to maintain such a high, non-stop reproductive output.

18. Loss of Defensive Instincts

A key behavioral adaptation across all domesticated species is a significantly diminished flight or defense response compared to their wild counterparts. Domesticated cattle will remain relatively calm in the presence of a human, whereas a wild aurochs would react with aggressive defense or immediate flight. This reduced instinct for self-preservation is the very foundation of tameness, making the animals manageable for husbandry and handling. While vital for domestication, it leaves these animals entirely vulnerable and dependent on human protection from predators.

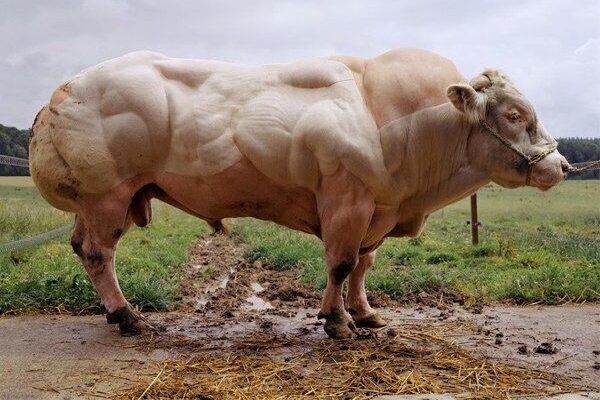

19. Specialized Muscle Hypertrophy (Double Muscling)

Some breeds of domestic cattle, most notably the Belgian Blue, have been bred to exhibit a genetic condition known as “double muscling,” or myostatin-related hypertrophy. This mutation inhibits the gene that typically restricts muscle growth, resulting in significantly increased muscle mass across the animal’s body. This adaptation maximizes meat yield, a highly desirable trait for human consumption. However, this extreme physique often leads to birthing difficulties, requiring veterinary intervention (often a Caesarean section), highlighting a physical adaptation that requires complex human medical support for the animal to reproduce successfully.

20. Enhanced Starch Digestion

Domestic dogs, unlike their wolf ancestors, possess more copies of the gene AMY2B, which produces amylase, an enzyme that breaks down starch. This genetic adaptation allowed early dogs to efficiently digest the high-starch leftovers from human agricultural settlements, an evolutionary advantage that cemented their bond with humans as hunter-gatherers transitioned to farming. This ability to thrive on a more omnivorous, carbohydrate-rich diet is a profound metabolic change that distinguishes the domestic dog and reflects thousands of years of dietary co-evolution with people.

21. Extreme Fat Reserves in Geese and Ducks

Certain breeds of domesticated geese and ducks, particularly those bred for liver production (e.g., for foie gras), exhibit a genetic propensity to develop exceptionally fatty livers. This is an extreme physiological adaptation that makes them highly susceptible to fatty liver disease when fed a human-controlled diet. While controversially induced by gavage (force-feeding) in some production systems, the genetic predisposition for efficient fat storage is an adaptation that was historically selected for by humans to yield a highly valued, calorie-dense product.

22. Short Legs and Achondroplasia

Many domestic breeds across species, such as Dachshunds, Corgis, and Basset Hounds, are characterized by extremely short legs due to achondroplasia (dwarfism). This trait was often selected by humans for functional purposes, like hunting badgers in burrows, or purely for aesthetic novelty. This physical adaptation, which reduces their ground clearance, makes them highly specialized for human-assigned tasks but limits their mobility and increases their risk of spinal issues, making them critically reliant on a safe, human-managed environment.

23. Loss of Camouflage Coat Color

In many domesticated species, including livestock and companion animals, the wild-type, cryptic coat colors (like the gray-brown of a wild cat or wolf) have given way to bright, non-camouflaging colors like white, black, red, and unique patterns. This loss of camouflage is a clear indicator of reduced predation pressure under human protection. A bright white goat or an orange cat would be easy prey in the wild, but in a farmer’s field, its visibility is not a liability and may even be advantageous for human herders.

24. Prolonged Fertility and Delayed Senescence

Some domestic animals, such as horses and cattle, tend to remain fertile and productive for longer into their lives compared to their wild relatives. While an old wild mare might struggle to raise a foal, a well-cared-for domestic broodmare can often be bred successfully well past that age. This is partly due to superior nutrition and healthcare provided by humans, but also a result of selective breeding to extend the useful, reproductive lifespan, maximizing the return on investment for the owner. This pushes the limits of their natural biology, extending their useful years within the domestic sphere.

25. The “Silent Heat” in Cattle

In the wild, bovines exhibit obvious, pronounced behavioral signs of estrus (or “heat”) to attract a mate. However, many modern dairy cattle breeds have developed what is known as “silent heat,” where the physical and behavioral signs of readiness to breed are greatly reduced or virtually absent. This subtle physiological change is a side effect of high milk production, where the massive diversion of energy to milk production alters hormone levels. This adaptation makes it difficult for farmers to detect when a cow is ready to breed without technological assistance, making the continuation of the herd entirely reliant on human reproductive management.

The evolution of these domestic creatures is a compelling story of co-existence, a testament to the profound influence humans have had on the natural world.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.

This story 25 Incredible Adaptations Seen Only in Domesticated Animals was first published on Daily FETCH