1. The Smell of Books Defined the Space

Stepping across the threshold was an olfactory experience as memorable as the visual one. The unique and powerful scent was a complex blend of elements: the acidic, woody aroma of aging paper and cardboard, the faint, sweet chemical smell of binding glue holding the hardcovers together, and the polished wood of the shelves and card catalog drawers. Mixed in might have been the waxy scent of floor polish or the dry, earthy smell of the building itself. This distinct fragrance, a combination of the musty and the manufactured, became the true “perfume of imagination” for a generation. It was an unmistakable signature that signaled a passage from the noisy playground world into a place of quiet focus and unlimited discovery, a scent that still triggers a rush of childhood memory today.

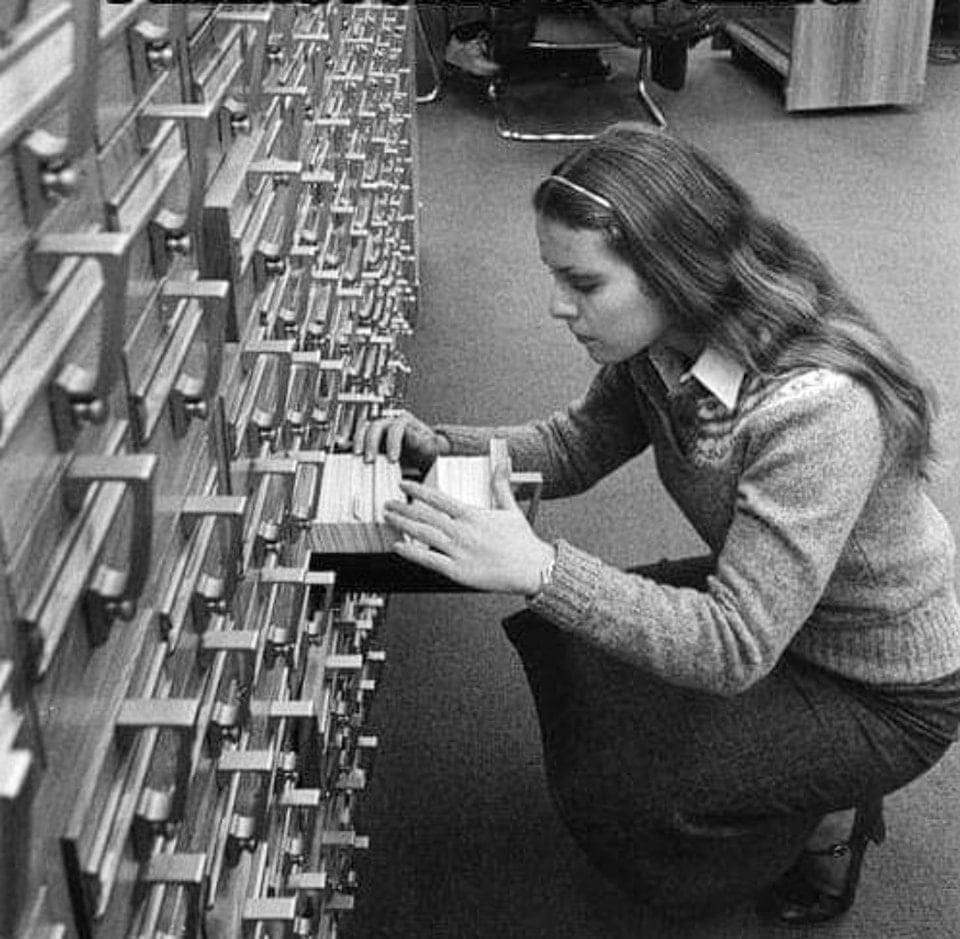

2. Card Catalogs Were the Internet of the Time

Before the digital age, the card catalog was the most crucial research tool a student had, a complex system of alphabetized 3×5 index cards stored in small, tightly packed wooden drawers. Every book in the library had at least three cards: one filed by the author’s last name, one by the book’s title, and one or more filed by subject. Learning to use the catalog meant mastering the Dewey Decimal System, a numerical classification for all non-fiction books, which was essential for locating a specific resource. Flipping through these brittle, slightly yellowed cards was a deliberate, hands-on ritual that inherently taught children the fundamentals of organization, patience, and meticulous research. It was the first lesson in information retrieval, grounding kids in a structured system that made the physical act of finding a book a satisfying intellectual victory.

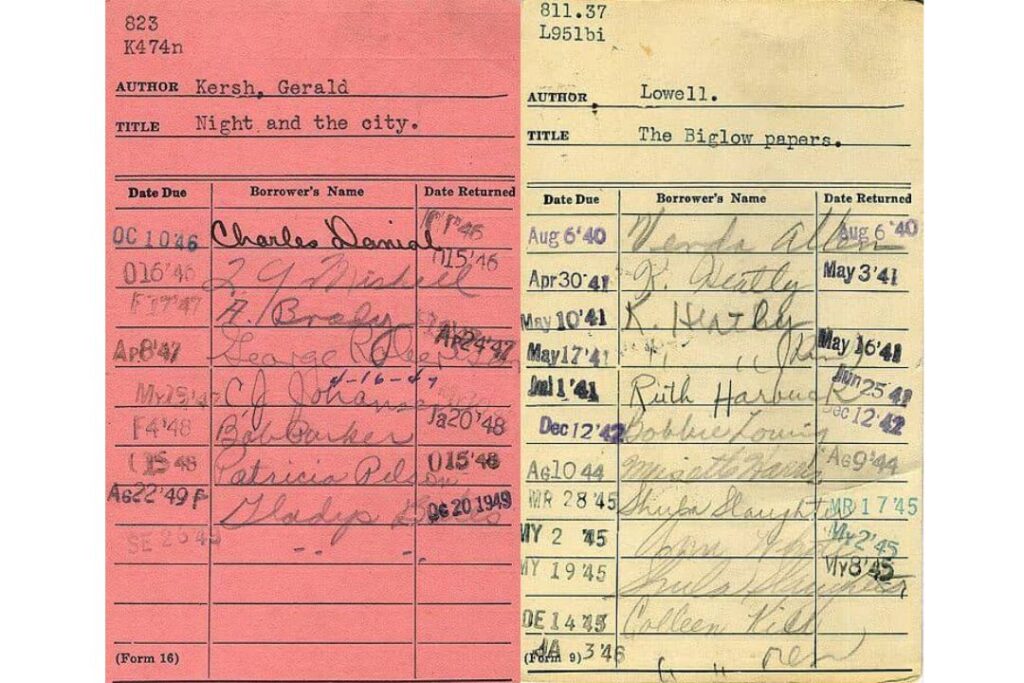

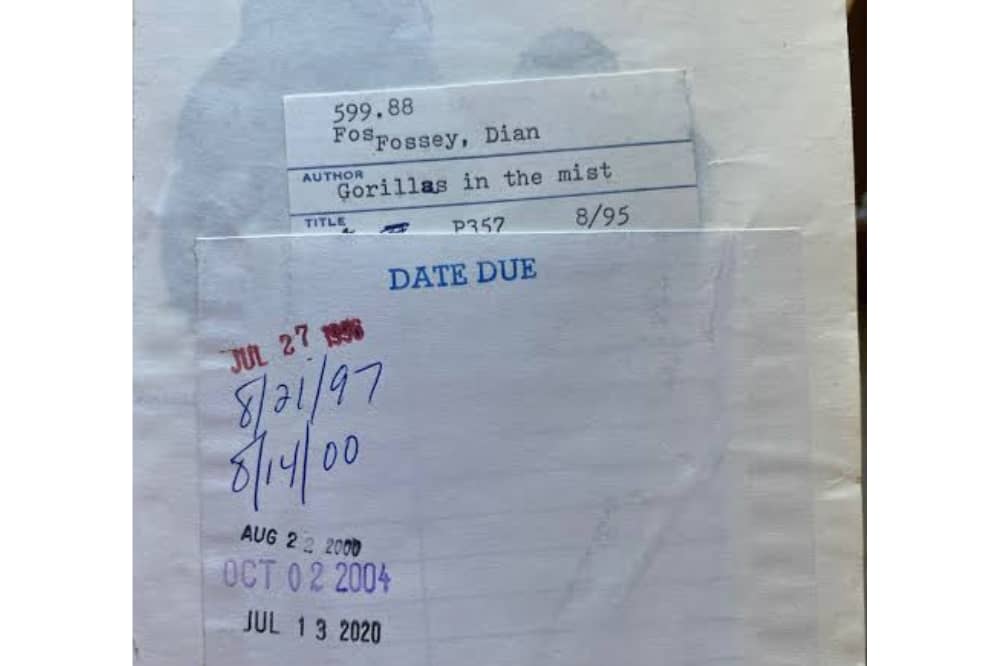

3. Library Cards Tracked Every Borrower

The act of checking out a book was a quaint, multi-step transaction centered on the physical library card and book pocket. Affixed to the front or back inside cover of every book was a small paper sleeve, or “pocket.” Inside, a stiff manila or white card contained the book’s title and often a list of stamped due dates. When a student checked out the book, the librarian would pull this card, manually write the student’s name or number on it, and then stamp the card and a corresponding “date due” slip (often pasted opposite the pocket) with the new return date. This simple, hands-on tracking system provided an immediate, personal record of responsibility. The card remained with the librarian until the book was returned, at which point it was quietly and satisfyingly slipped back into the pocket, linking the current reader to a long lineage of past and future borrowers.

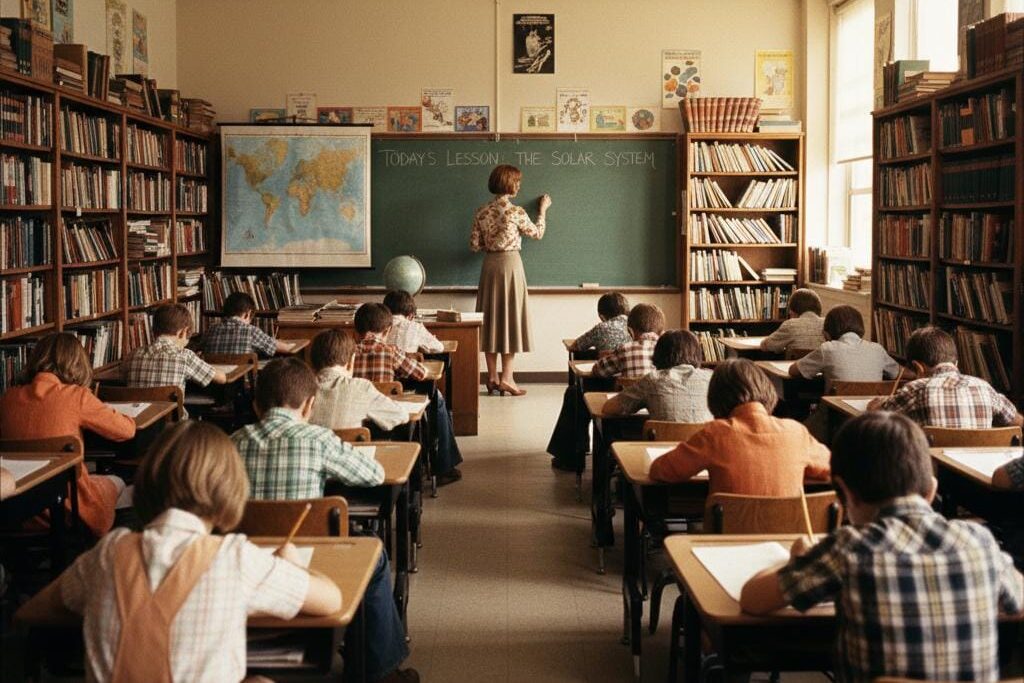

4. The Librarian Ruled with a Single “Shhh”

The elementary school librarian was not just an archivist; they were the official guardian of the peace and the ultimate authority on quiet decorum. Often fitting a distinct archetype, perhaps wearing a practical skirt suit, sensible shoes, and sometimes glasses on a beaded or gold chain, their power lay in the silent gesture. A quick, precise finger to the lips or a firmly whispered “shhh” could instantly halt the movement and chatter of an entire class of restless students. This enforced silence was a crucial part of the library’s educational function, training children to understand that the space was dedicated to serious focus and deep concentration. They were the champions of literacy, but their primary, non-negotiable rule was one of respectful quiet, establishing an atmosphere of reverence for the volumes and the readers within.

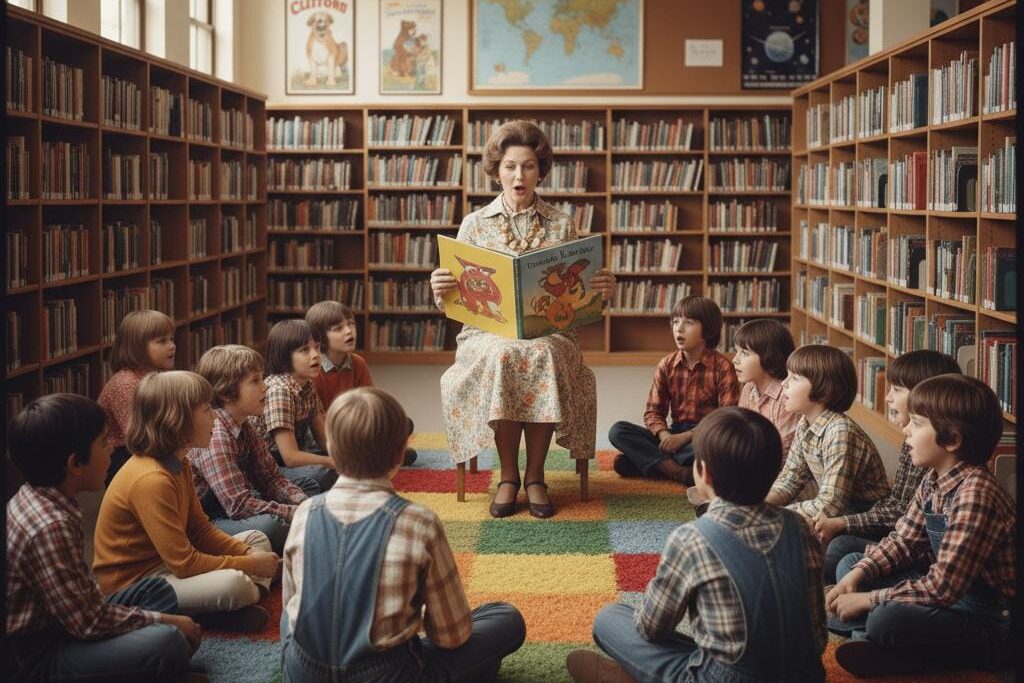

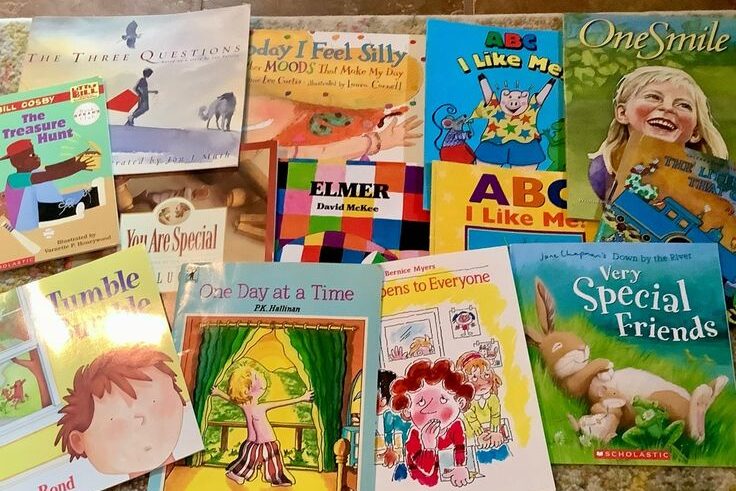

5. Storytime Made Books Come Alive

The centerpiece of many elementary library visits was storytime, a scheduled period designed to introduce young readers to the joy of narrative and the magic of picture books. Students would gather not at desks, but cross-legged on a colorful rug or a designated circle on the floor, all eyes on the librarian who sat in a low chair. The librarian would hold the book up, often with a practiced ease, making sure to slowly pan the illustrations across the eager faces in the audience. They used dramatic voices, varied pitch, and expressive gestures to bring characters like Clifford the Big Red Dog, the Berenstain Bears, or Maurice Sendak’s Wild Things vividly to life. This communal, auditory experience was formative, transforming a collection of printed pages into a shared, emotional, and captivating event, sparking the initial, vital connection between a child and the world of reading.

6. Scholastic Book Clubs Brought Catalogs to Desks

One of the most exciting periodic events was the arrival of the Scholastic Book Club flyers, thin newsprint catalogs that were distributed directly to students’ desks. These flyers offered an array of affordable, popular paperback books that were often more current or culturally relevant than the library’s hardcover collection. Kids would excitedly flip through the pages, circling their choices with a pencil, lured by titles like The Boxcar Children, Goosebumps (later in the decade/early 80s), joke books, and various young adult novels. The ultimate ritual involved bringing a small amount of cash, often folded and secured in an envelope, to school for the order. Weeks later, the arrival of a massive cardboard delivery box, often smelling distinctly of new paper and ink, would cause a palpable buzz in the classroom, delivering fresh, personally chosen treasures.

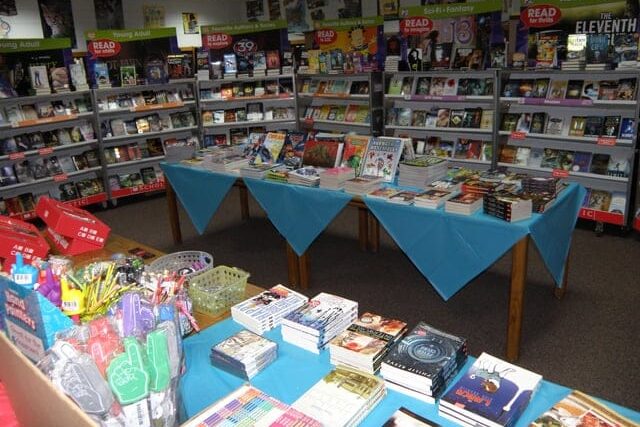

7. The Annual Book Fair Transformed the Library

The Annual Book Fair was a short-lived but beloved event that temporarily converted the tranquil library into a commercial festival of words. Tables and carts were brought in, laden not only with new books, many of which were glossy hardcovers unavailable elsewhere, but also with smaller impulse items. These irresistible additions included colorful erasers, novelty pens, bookmarks, and posters featuring everything from pop culture icons to kittens and horses. Students would arrive clutching envelopes of cash or handfuls of coins saved from their allowances, meticulously planning their purchases. The fair’s environment, buzzing with a controlled excitement, gave kids a rare sense of autonomy and ownership over their reading choices, transforming the act of buying a book into a special, joyful occasion that was looked forward to all year.

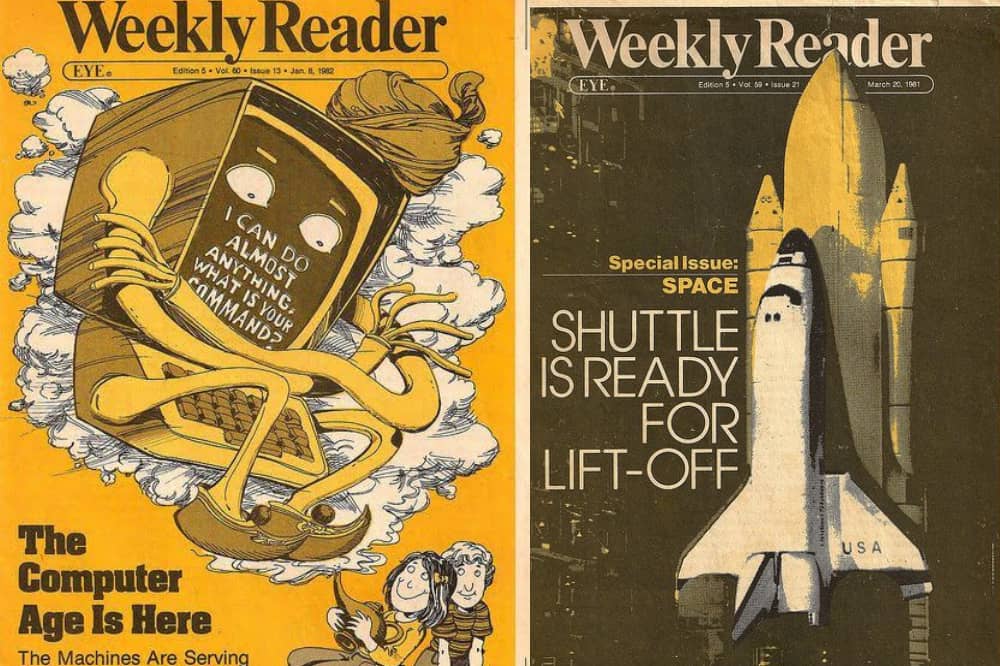

8. Weekly Reader Arrived Fresh and Exciting

The Weekly Reader (and similar classroom publications like Scholastic News) was a thin, easily digestible magazine that arrived weekly, providing elementary students with their first consistent, age-appropriate exposure to current events and world affairs. Published on simple newsprint, it mixed short articles on national and global news with engaging puzzles, educational games, and feature stories about science, history, or culture. Holding the Weekly Reader felt distinctly grown-up; it was essentially a newspaper filtered and tailored specifically for a young audience. It served as a vital bridge between the timeless stories of fiction and the rapidly changing reality of the outside world, teaching kids to engage with information that was timely and factual, fostering an early sense of civic awareness and general knowledge.

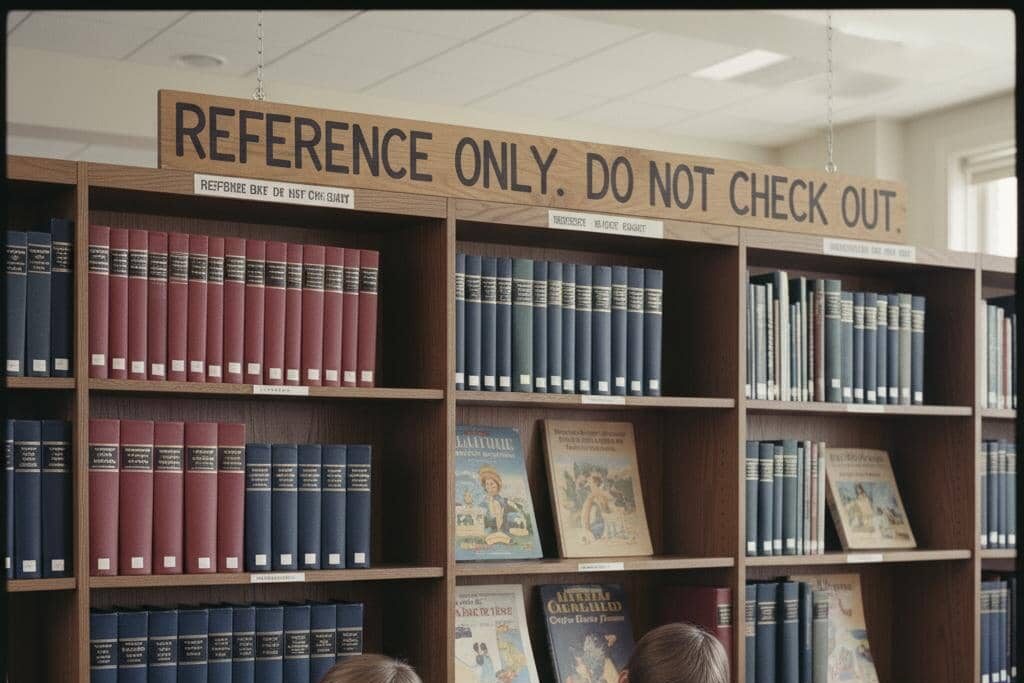

9. Reference Shelves Felt Sacred

The reference section of the library stood apart, both physically and in status, from the circulating collection. These shelves contained the crucial, large-format books, encyclopedias, unabridged dictionaries, and large atlases, which were almost always marked with the stern warning “REFERENCE ONLY. DO NOT CHECK OUT.” This rule meant the books had to be used in situ, often hunched over a nearby table. Because these volumes were permanent fixtures, their pages became the shared intellectual property of the entire school. Students tasked with research projects would meticulously take notes by hand or copy text, as photocopying was often unavailable or restricted. This section instilled a sense of purpose and seriousness, teaching children to treat certain materials with a higher level of reverence and care due to their unique, non-circulating status.

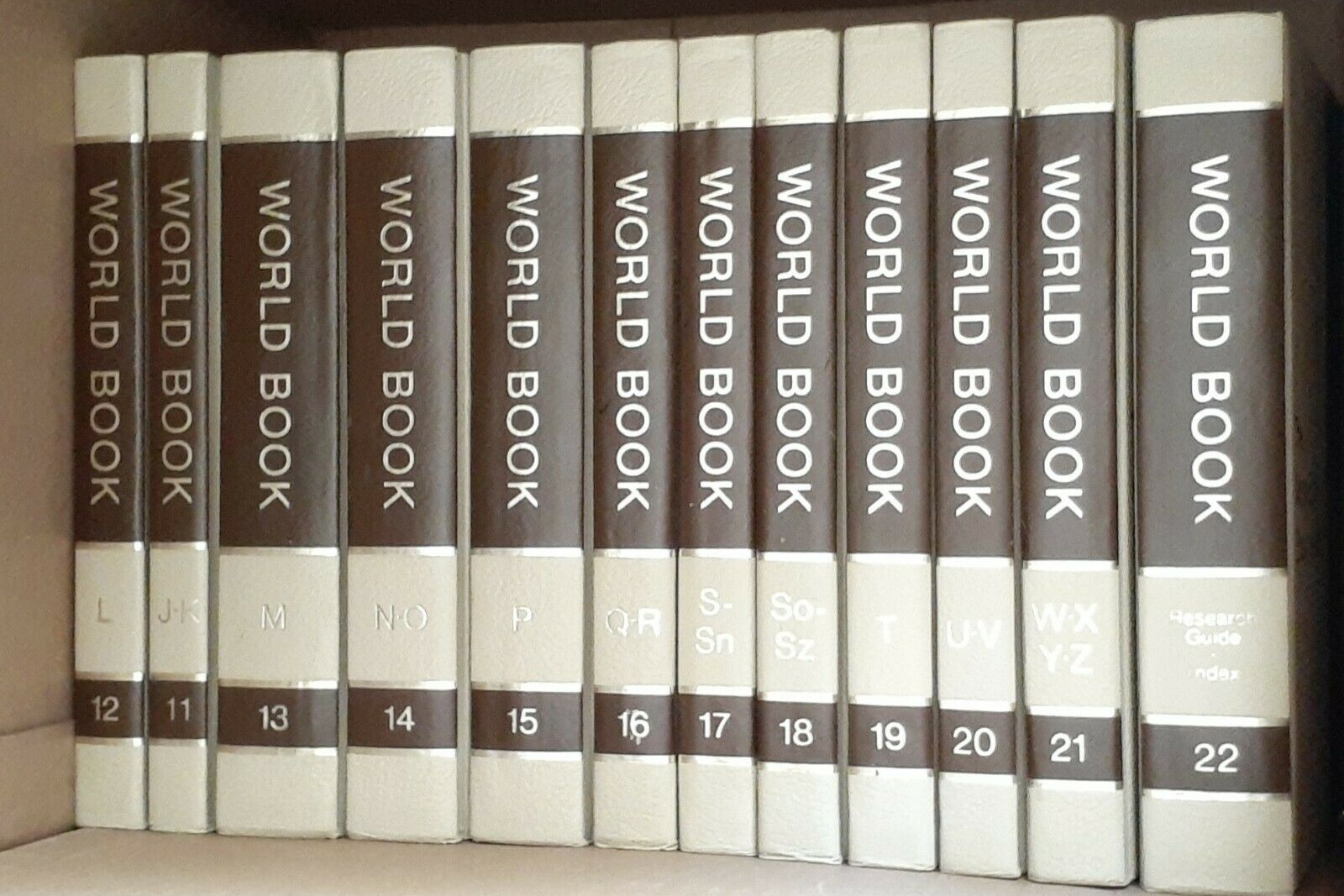

10. Encyclopedias Were Google in Print

Before search engines democratized knowledge, the multi-volume encyclopedia set was the ultimate repository of all human information, the undisputed champion of the reference section. Sets like World Book or Compton’s were instantly recognizable by their uniform, often dark-colored bindings and gold lettering on the spine. Students would consult these massive, heavy volumes, arranged strictly in alphabetical order, to find foundational facts on everything from the history of Egypt to the life cycle of a frog. The experience involved the satisfying ritual of pulling the correct volume, finding the right guide words at the top of the page, and poring over the text. The articles were heavily illustrated with glossy color plates and detailed diagrams, making the act of reading about a distant country or a complex scientific concept a visually rich and absorbing activity.

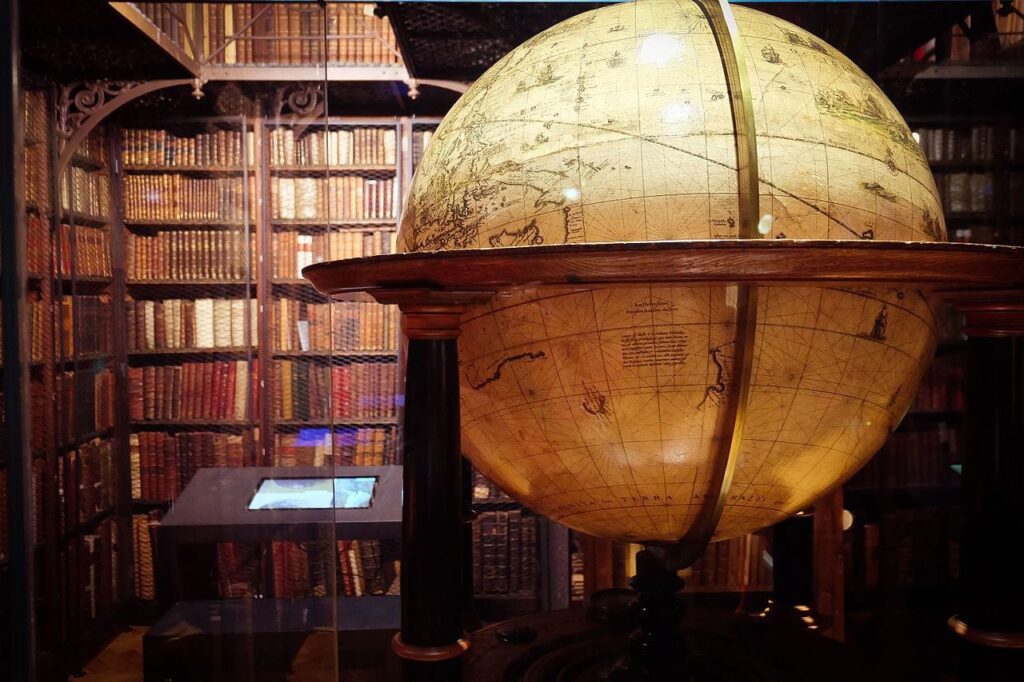

11. Globes Spun Dreams of Travel

A standard, non-negotiable fixture in the 1970s school library was at least one large, floor-standing globe on a metal or wooden base. In an era before instant satellite imagery, the globe was a tactile, three-dimensional representation of the Earth, a marvel of cartography and a powerful tool for visual learning. Kids were inevitably drawn to its presence, compelled to give it a spin, watch it rotate on its axis, and then jab a finger at a random spot, a far-off country like Madagascar, a city they’d heard mentioned on the news, or a place they dreamed of visiting. The globe served as a constant, silent catalyst for geographical curiosity and daydreams of faraway lands, reminding children that the world was vast and full of places waiting to be explored, a constant spark for imagination that reached beyond the classroom walls.

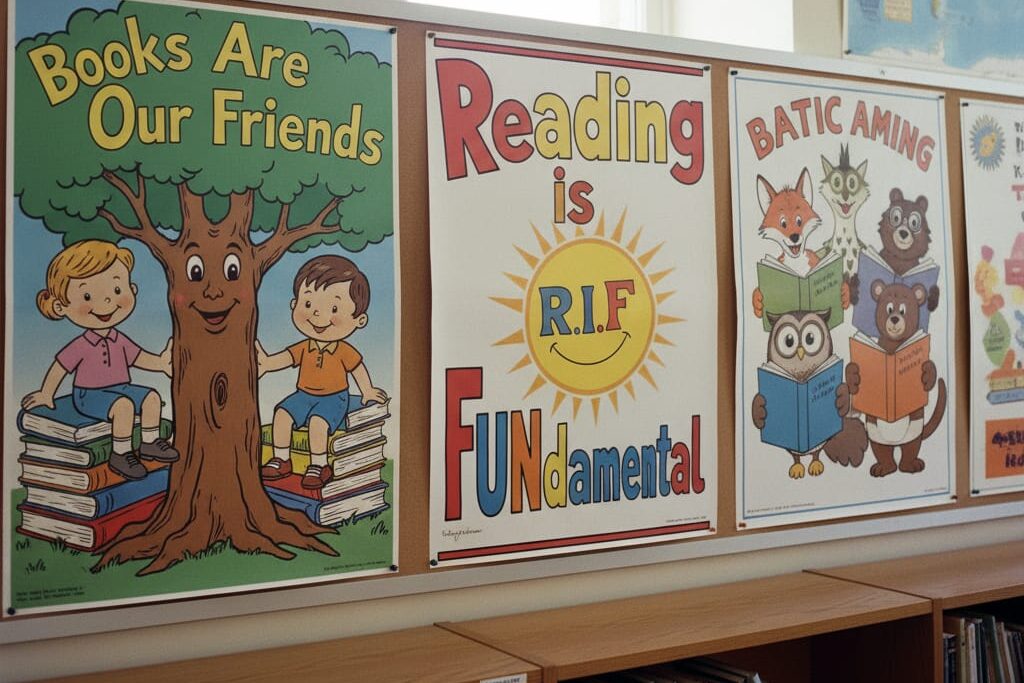

12. Posters Encouraged Reading with Simple Slogans

Library walls were often decorated with brightly colored, cheerful posters designed to promote literacy and the joy of reading. These visuals were part of coordinated national campaigns or simple, locally made graphics, but they shared a common, straightforward aesthetic. Slogans like the highly influential “Reading is FUNdamental” (often abbreviated as “R.I.F.”) were prominently featured, sometimes alongside friendly, non-threatening cartoon characters. Other common messages included “Books Are Our Friends,” and images of children or animals happily engaged with books. These weren’t sophisticated ad campaigns; they were direct, positive affirmations intended to create a warm, welcoming, and encouraging environment. The consistent presence of these simple, bold graphics helped to reinforce a lifelong, positive association between reading and essential values like fun, friendship, and knowledge.

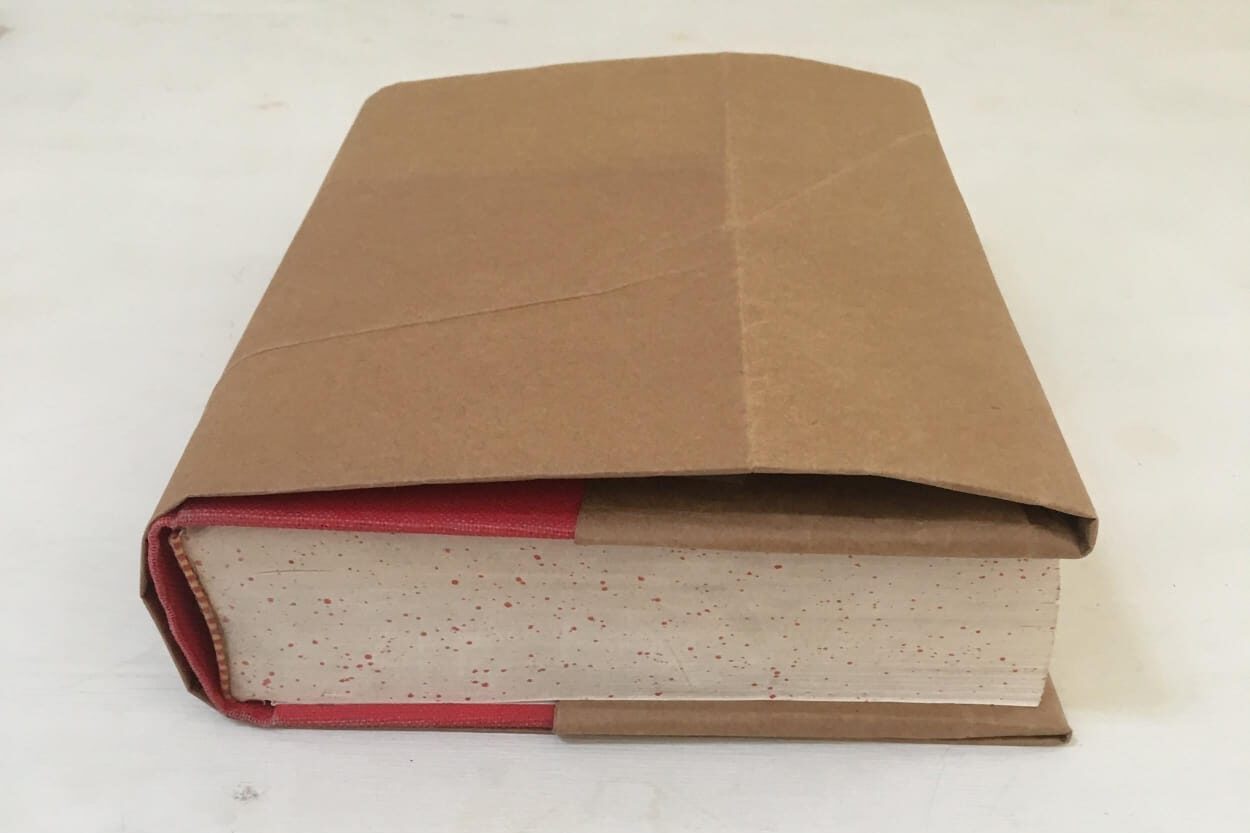

13. Brown Paper Book Covers Crinkled with Age

A practical tradition in many budget-conscious school districts was protecting the often-expensive library hardcovers with homemade book covers made from readily available materials. The most common was plain brown paper (often heavy-duty butcher paper) or, less formally, opened-up leftover grocery bags. The covers were folded precisely to fit the book, sometimes secured with tape, and served as a cheap, effective shield against spills, scuffs, and bent corners. This utilitarian practice, however, created a blank canvas for students. Many kids would doodle, draw pictures, or personalize their temporary cover with their name and class. The characteristic crinkle and rustle of the paper was the sound of a book being opened, and the signs of wear, a ripped corner or a water stain, told a subtle story of the book’s travels through the hands of previous students.

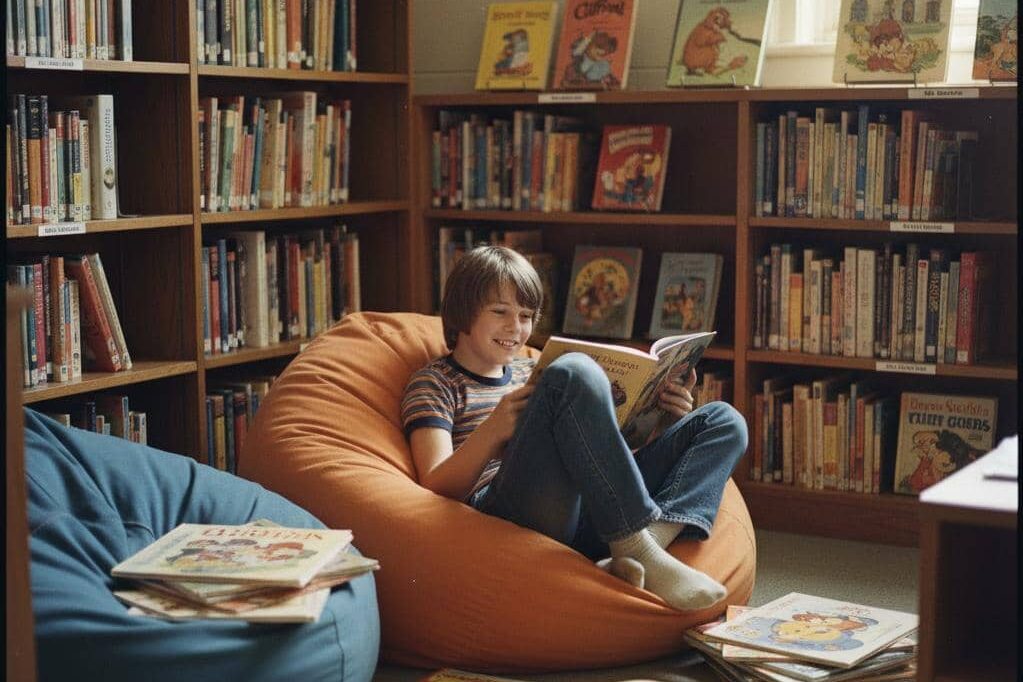

14. Beanbag Chairs Made Reading Cozy

In some libraries, particularly those that adopted more progressive educational philosophies in the late 1960s and 1970s, designated reading areas featured soft furnishings to encourage relaxed, sustained reading. The beanbag chair was the quintessential piece of 1970s comfort furniture, a large, floppy sack filled with polystyrene beads. These chairs, or sometimes simple large pillows, were often placed in a quiet corner away from the main aisles. Claiming one of these coveted spots was a small but significant victory for a child, offering a snug, comfortable cocoon away from hard desks and structured seating. Nestled in a beanbag chair, a child could quite literally disappear into a book, allowing the physical comfort to enhance the mental escape into a fictional world, fostering the idea that reading was a truly pleasurable, restorative activity.

15. Magazines Offered Windows to Hobbies

While the majority of the library was dedicated to hardcover fiction and non-fiction, a small but important section housed magazines aimed specifically at elementary-age children. These periodicals served as an important bridge between structured academic reading and playful, interest-driven learning. Popular titles included Highlights for Children, famous for its “Goofus and Gallant” morality lessons and the hidden pictures puzzle, and nature-focused publications like Ranger Rick. Others, like Cricket (a literary magazine), offered high-quality short stories and poems. Flipping through these glossy, thin pages was a fun, quick diversion. They introduced kids to the worlds of animals, crafts, riddles, and jokes, making reading a diverse, multi-faceted activity that catered to varied interests and helped students discover new hobbies and passions outside of required reading lists.

16. The Date Stamp Echoed Authority

The final, definitive step in the checkout process was the ceremonial clunk of the date stamp. The librarian would firmly press the stamp, a small, handheld mechanism with a rubber dial for the month and day, onto the due date slip inside the book. This sound was a distinct, satisfying noise that marked the end of the transaction and the beginning of the borrower’s responsibility. It was a tangible, immediate symbol of imminent accountability, turning a piece of paper into a legal-like document. The presence of that stamped date served a psychological function: it made the act of taking the book out feel official and important, instilling a sense of grown-up trust and duty in the young student, who was now bound by a clearly established deadline to return their borrowed property.

17. Overdue Books Carried Real Weight

The consequences of an overdue book were often a source of significant, if minor, childhood anxiety. The first notification was usually a small, brightly colored late slip discreetly tucked into a folder or backpack by a teacher. This slip served as a formal, embarrassing reminder of a broken rule. While the fines themselves were typically minuscule (often just a penny or two per day), the true weight of the infraction was moral and social. Some children, overwhelmed by the feeling of having failed to meet a responsibility, would resort to hiding the book under a bed or in a closet. The return of an overdue book was a quiet, sometimes shame-filled ritual, with the child hoping to slip it back to the librarian without drawing attention to the faint, but noticeable, late date on the stamped slip.

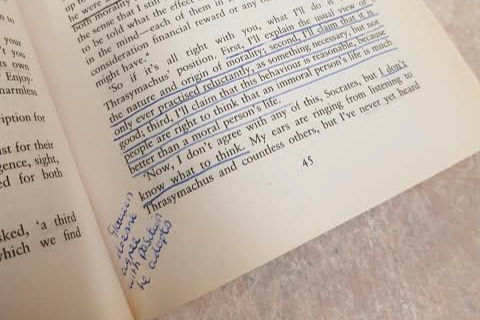

18. Margins Whispered with History

A surprising intimacy could be found in the subtle markings left behind by previous readers. While outright defacing a book was strictly forbidden, many volumes, having passed through hundreds of young hands, contained faint, inadvertent traces of their past lives. These might include small, biro or nearly erased pencil doodles in the lower margins, a lightly underlined passage that deeply resonated with a prior reader, or an occasional, brief pencil note written alongside a confusing word or passage. Discovering these little interventions felt like uncovering a secret message, a quiet, unintentional collaboration between strangers separated by years. These subtle marks made the reading experience communal, providing tangible proof that other children had wandered the same pages, and had been equally captivated, confused, or delighted by the story.

19. The Rolling Ladder Was Off-Limits and Alluring

In libraries with high ceilings and tall, wall-to-wall shelving, the rolling ladder was an object of almost magical fascination. Typically made of wood or metal, it was mounted on a track and could be smoothly pushed along the length of the stacks. The librarian, often smaller than the towering shelves, would ascend the ladder with casual ease to retrieve a book from a hard-to-reach top shelf. For the elementary student, this tool was strictly off-limits and forbidden, a clear rule that only amplified its mysterious allure. Watching the ladder glide and seeing the librarian perched high up felt like glimpsing a secret, adult skill or a unique tool of the trade. The rolling ladder symbolized the great height and depth of the library’s knowledge, and the ultimate reward that came with mastering the library’s geography.

20. Reading Contests Inspired Rivalry

To motivate students and track literacy development, many teachers and librarians implemented reading contests throughout the school year. These competitions ranged from simple class-wide charts to elaborate, themed displays. The most common method was using gold stars or construction paper cutouts (like fish, hot air balloons, or apples) to visibly track each student’s progress on a bulletin board. Every book successfully read and reported on earned the student an addition to their chart. Filling a row or reaching a certain number of books became a point of significant, yet usually friendly, rivalry and pride. These contests successfully gamified reading, turning the pursuit of knowledge into a sport where children were actively encouraged to push their boundaries, read one more chapter, and ultimately discover the reward that lay in finishing a book.

21. The Hush Was a Rare Kind of Peace

The atmosphere of quiet was a defining characteristic of the 1970s elementary school library, setting it apart from every other space in the school building. Unlike the chaotic volume of the playground, the clatter of the cafeteria, or the ambient noise of a busy classroom, the library offered a deliberate, enforced sense of tranquility and calm. The soundscape was distinct: the only noises were the gentle shuffle of feet on the floor, the soft thump of a book being placed on a table, and the quiet, rhythmic turning of paper pages. For many children, this hushed environment was a form of sanctuary, a place where their own thoughts weren’t competing with external noise. It fostered deep concentration and provided a valuable, almost therapeutic respite from the busy pressures of school life.

22. Magically, Books Always Returned Home

Despite the thousands of books in circulation, the constant movement of children, and the inevitable occasional loss, there was a reassuring sense of stability and permanence to the library’s collection. The books, though loved and heavily used, always found their way back to the shelf. The physical condition of the volumes, the scuffed corners, the faded covers, the bent spines, and the signs of wear on the page edges, told a rich, unspoken history of their journey. Each imperfection was proof of the book’s successful passage through hundreds of young hands across many different grade levels. This cycle of borrowing and returning created a powerful, silent lesson in community and shared ownership, assuring every new borrower that the story they were about to read had been a beloved companion to many children who came before them.

23. The Library Sparked Curiosity Beyond Assignments

While a primary function of the library was to serve as a resource for teacher-assigned research projects, its true power lay in encouraging spontaneous, unscheduled discovery. The Library could even double as a class. A teacher might send a student in search of a book on mammals, but on the way, the child’s eye would be inevitably snagged by a spine with a mysterious title or a brightly illustrated cover. They would find themselves wandering into sections they never intended to visit, suddenly discovering a ghost story anthology, a fascinating book of optical illusions, or an easy-to-read mystery novel. This freedom to wander and follow an impulse was a vital aspect of the library experience. It taught students that knowledge acquisition wasn’t just mandatory; it was a personal adventure driven by their own budding curiosity and unrestricted interests.

24. The Elementary School Library Was a Sanctuary

Ultimately, the 1970s elementary school library was far more than its constituent parts of shelves, stamps, and paperbacks. It was a multi-sensory refuge, a place defined by the scent of old paper, the quiet authority of the librarian, the welcoming comfort of the beanbag corner, and the sheer volume of untapped knowledge contained within the walls. It served as a vital third space for a generation, separate from the home and the structured classroom, offering a unique blend of personal responsibility (the due date stamp) and boundless freedom (the open shelves). For the 1970s kid, it was the definitive place where imagination could bloom quietly and continuously, a sanctuary that taught the fundamental lesson that the greatest adventures could be found not by leaving, but by simply opening a book.

That scent of paper and wood polish is still strong, isn’t it? For a generation, the elementary school library was our first real encounter with research and the profound pleasure of a story. What was the first book you ever checked out of a library with your own card?

This story 24 Memories of the 1970s Elementary School Library was first published on Daily FETCH