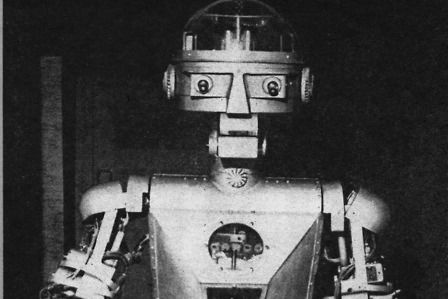

1. Early Robot That Could Smoke a Cigarette in 1939

The 1939 New York World’s Fair, themed “The World of Tomorrow,” introduced visitors to dazzling technologies and hopeful visions of the future. Yet, among the sleek, modern displays, was “Elektro,” a seven-foot-tall robot from Westinghouse. Elektro could talk, count on his fingers, and, oddly, smoke a cigarette. While his abilities were impressive for the time, the cigarette-smoking skill was a peculiar inclusion, an unnecessary human vice programmed into a machine meant to represent the future of automation. The fair promised sophisticated automation, but a robot engaging in a decidedly unhealthy habit provided a strange, anachronistic touch to the “World of Tomorrow.”

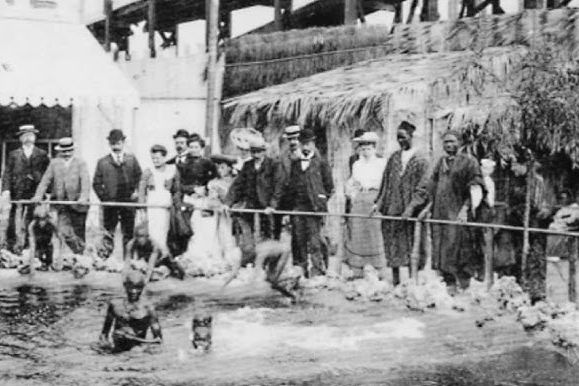

2. The Human Zoo at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair

The Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis became notorious for its “human zoos,” which showcased indigenous people from around the world, presented as “primitive” examples of humanity. A particularly disturbing example was the display of over 1,000 Filipinos, including members of the Igorot tribe, who were forced to live in reconstructed villages and perform rituals like dog-eating (which was not their daily custom but a feature the organizers exaggerated for sensationalism). This deeply racist practice, justified under the guise of “anthropological study,” stood in stark contrast to the fair’s supposed celebration of global progress, serving instead as a bizarre and unsettling cultural exhibition that reinforced harmful colonialist stereotypes.

3. The Great Butter Sculpture of 1876

At the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia, an artist named Caroline Shawk Brooks unveiled a life-sized statue of a sleeping girl, only the medium was a solid block of butter. Housed in a refrigerated room to prevent melting, an innovative necessity for the time, the sculpture became a massive, and decidedly odd, sensation. While the fair was meant to showcase American technological and industrial might, the enormous popularity of this edible artwork highlighted a Victorian fascination with ephemeral art and spectacle. Brooks went on to make a career of butter sculpting, a peculiar art form that certainly delivered a memorable, if perishable, experience far removed from the promise of steam engines and telegraphs.

4. Giving Away a Baby as a Prize in 1909

The Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle had many exhibits touting the wealth and potential of the Alaskan territory, but one particular stunt was beyond unusual. To promote the exhibition and potentially boost attendance, one concession attempted to give away a three-month-old baby girl as a raffle prize. The child, known as “Miss Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition,” was eventually withdrawn from the raffle due to public outrage and legal intervention, being instead placed in a foster home. This disturbing episode remains a bizarre and uncomfortable footnote in fair history, a marketing ploy that spectacularly failed to understand the boundaries between publicity and human decency.

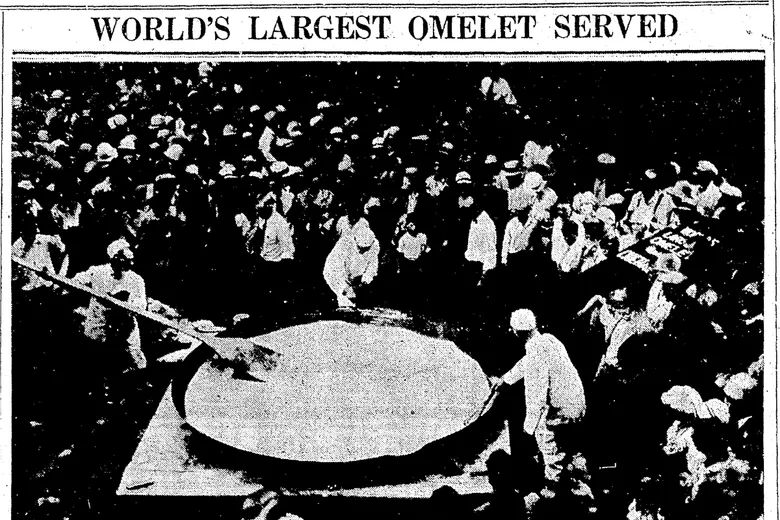

5. The World’s Largest Omelet in 1967

Expo 67 in Montreal was an icon of optimistic mid-century futurism, featuring revolutionary architecture like Habitat 67 and the Biosphere. However, one of its most memorable, and strangest, culinary displays was the creation of a massive omelet by a French delegation. Prepared on a specially-made, giant cooking surface, this gargantuan breakfast dish used thousands of eggs. It wasn’t a technological breakthrough or a vision of future living; it was just a massive egg dish for public consumption. Its sheer scale made it an amusing, absurd spectacle, an over-the-top moment of national pride that delivered a surprisingly simple meal in an incredibly complex and excessive manner.

6. The Corn Palace Architecture in 1893

The World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago was famed for its majestic “White City,” showcasing classical architecture and the latest industrial achievements. However, one structure that stood out for its sheer oddity was the Nebraska Corn Palace. Constructed entirely out of corn cobs, stalks, and other grains, this building was intended to demonstrate the agricultural bounty of the American heartland. While it achieved its goal, the building’s materials made it susceptible to the elements and pests, demanding constant and costly maintenance. The sight of an ornate palace built entirely of food was a bizarre, almost surreal, spectacle contrasting sharply with the fair’s high-tech, marble-like aesthetics, transforming a symbol of plenty into a curious, biodegradable oddity.

7. The Baby Incubator Exhibit of 1897 and Beyond

While the world’s fairs promoted many new inventions, the use of premature baby incubators was initially met with skepticism by the medical community. At the Trans-Mississippi and International Exposition in Omaha (and later at fairs in Chicago, Buffalo, and New York), Dr. Martin Couney ran a successful, self-funded exhibit where he openly displayed and cared for premature infants in these newly developed incubators. Fairgoers paid an admission fee to view the babies, essentially turning a vital medical service into a paid attraction. The money collected was used to fund the babies’ care. In an unexpected twist, the fairgrounds became the proving ground for a life-saving technology that established its legitimacy long before hospitals were willing to adopt it, making a medical necessity a strange form of public entertainment.

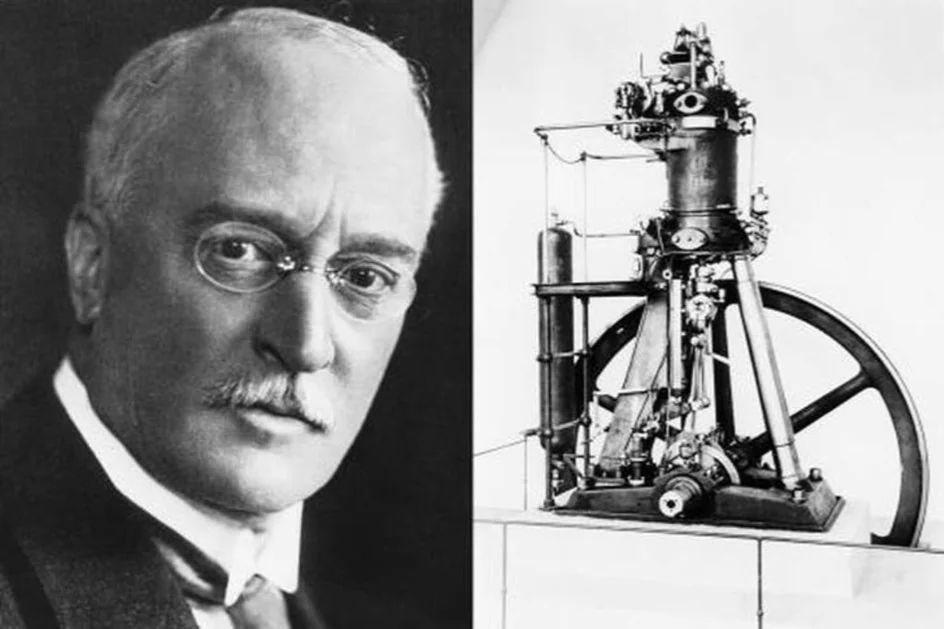

8. The Diesel Engine Running on Peanut Oil in 1900

The Exposition Universelle in Paris debuted numerous marvels, yet one of the most historically important, and weirdly prophetic, exhibits was the engine designed by Rudolf Diesel. His revolutionary diesel engine was demonstrated running successfully not on traditional fossil fuel, but on peanut oil. Diesel himself was a huge proponent of using plant oils, believing they were the future of engine power. While the industrial world largely pivoted to petroleum, the brief, successful demonstration of an engine powered by common peanut oil provided a strange, almost forgotten hint at future biofuel technologies, a temporary curiosity that would only become a key conversation a century later.

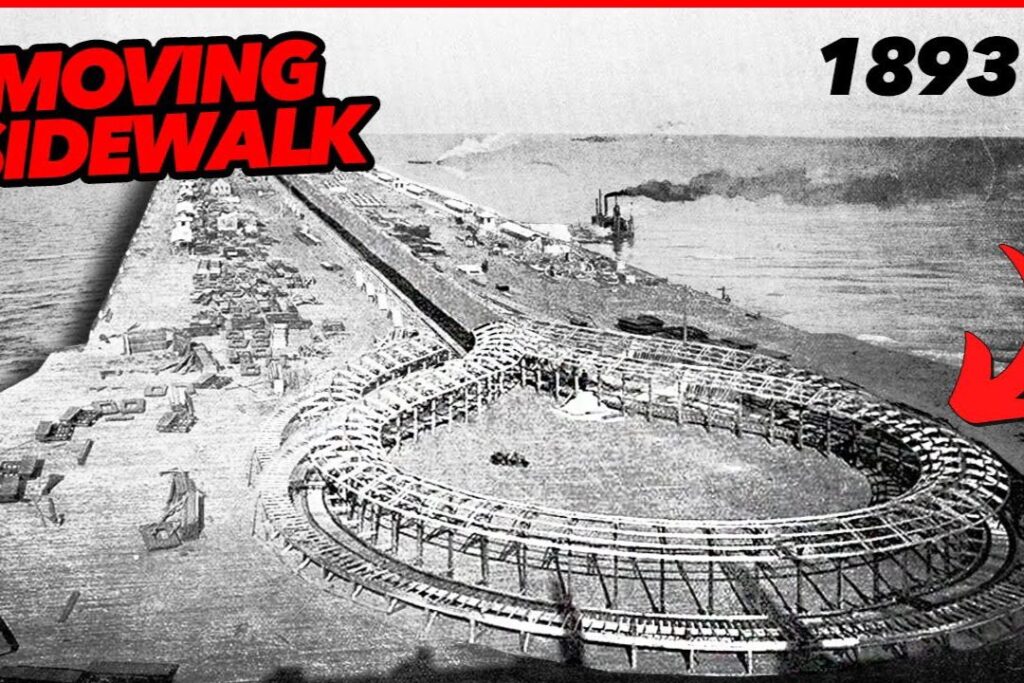

9. The “Slidewalk” Moving Walkway in 1893

Visitors to the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago were promised an effortless journey through the grounds by a new invention: the moving walkway. Dubbed the “Slidewalk,” this early escalator-like system ran along a pier by Lake Michigan. While intended as a futuristic method of mass transit, it proved to be a source of confusion and amusement. Many fairgoers struggled to safely board and disembark the moving platform, resulting in comical falls and awkward stumbles. The technology was functional, but its impracticality for the general public at the time revealed a gap between the vision of effortless future travel and the reality of early 20th-century public coordination.

10. The World’s Largest Cheese in 1893

Another oddity that drew immense crowds at the 1893 Chicago fair was the colossal “Mammoth Cheese” from Canada. Weighing over 22,000 pounds, this enormous cheddar was intended to showcase Canada’s agricultural prowess. The novelty of the sheer scale of this dairy product made it a huge attraction. Visitors lined up simply to gawk at the gigantic wheel of cheese, which required special refrigeration and transportation. The exhibit proved that in the grand theatre of a World’s Fair, a truly massive, simple object, like an absurdly oversized block of cheese, could compete with the most complex new technological marvels for public attention.

11. Million-Dollar Money Tree in 1964

At the 1964 New York World’s Fair, the American Express Pavilion, which offered essential services like currency exchange, erected a bizarre attraction to draw crowds: the “Money Tree.” This 26-foot-tall, artificial structure was symbolically adorned with more than one million dollars’ worth of real paper currency and foreign notes from around the world. The notes were arranged like “leaves” on the branches, representing the international economic forces that the company facilitated. In a fair dedicated to technological and social progress, the spectacle of actual wealth literally growing on a tree was an unusual, literal display of capitalism and extravagance—a bizarre, glittering financial garden that was a purely promotional, not futuristic, marvel.

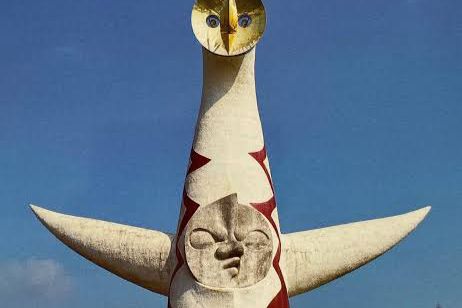

12. “The Tower of the Sun” and Its Disfigured Face in 1970

Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan, focused on the theme “Progress and Harmony for Mankind,” featuring sleek, modernist design. The centerpiece was the “Tower of the Sun,” a sculptural creation by artist Tarō Okamoto. The tower was massive, reaching 230 feet, and its bizarre, ancient-looking “Golden Mask” face stood out dramatically. While the surrounding architecture was futuristic, the tower itself appeared as a strange, almost grotesque, primitive idol, a deliberate contrast intended by the artist. This centerpiece represented a rejection of purely technological progress, instead highlighting a weird, unsettling blend of humanity’s primal past and its technological future, leaving many fairgoers scratching their heads.

13. The Voder, an Early Voice Synthesizer, in 1939

During the same 1939 New York World’s Fair that showed off Elektro the smoking robot, Bell Labs debuted the “Voder” (Voice Operating Demonstrator). This complex machine was one of the world’s first working electronic speech synthesizers. The demonstration, which required a specially trained female operator to “play” the machine like a keyboard to produce recognizable human speech, was a technological marvel. However, the resulting synthetic voice was often described as eerie, mechanical, and slightly unsettling, producing a strangely robotic, disembodied sound. The Voder promised the future of communication but delivered a voice that was more alien than human, a weird auditory peek into the coming digital age.

14. The Temple of Music and Art Made of Salt in 1915

The Panama-California Exposition in San Diego celebrated the opening of the Panama Canal with grand, Spanish Colonial Revival architecture. One of the strangest structures, however, was the exhibit built by the state of Utah: a “Temple of Music and Art” constructed primarily out of huge blocks of salt. Intended to demonstrate the state’s vast mineral resources, the salt structure was a bizarre, glittering curiosity. While beautiful, its material was highly susceptible to moisture, demanding constant vigilance from caretakers to prevent its dissolution. It was an ephemeral, edible piece of architecture, a weirdly unstable choice for a structure meant to celebrate permanence and progress.

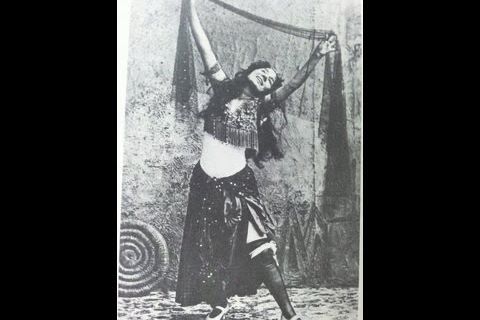

15. The “Streets of Cairo” Exhibit and the Beginning of the Cooch Dance in 1893

The World’s Columbian Exposition featured a midway that included the “Streets of Cairo,” a cultural village exhibit. Here, the Algerian dancer known as “Little Egypt” performed a risqué dance that was quickly dubbed the “cooch dance.” While intended as a taste of “exotic” foreign culture, the dance was significantly sensationalized for the American audience. It became an immediate scandal and a massive, unpredicted hit, introducing a new form of entertainment that bordered on the scandalous. The fair promised education and technology but delivered instead a hugely popular, strangely hypnotic dance that launched a new, slightly shocking, tradition in American popular entertainment.

16. The Full-Scale Model of a Moon Colony in 1964

The 1964 New York World’s Fair was a hub of space-age fantasy, and one exhibit provided a look at a full-scale model of a future moon colony. It was a serious, scientific attempt to envision lunar habitation, complete with pressurized domes and a stark, futuristic interior. However, the model, in its effort to be technically accurate and sterile, struck many fairgoers as excessively cold and uninviting, a future that was perhaps too sparse and lonely to truly desire. The weirdness wasn’t in the concept, but in the lack of human warmth, presenting an alienating vision of a technical, but deeply unappealing, future home.

17. The “Automated Butler” of 1962

The Seattle World’s Fair (Century 21 Exposition) focused heavily on robotics and a sleek, automated future. One popular demonstration was the “Automated Butler,” a device meant to serve food and drinks on a complex, guided track system within a home. While a nod to convenience, the contraption often proved slow, clunky, and prone to mechanical errors, sometimes dropping or spilling its cargo. The exhibit promised effortless domestic life via automation but delivered a weirdly inefficient and temperamental servant, highlighting the frustrating gap between an inventor’s vision and practical, reliable household robotics.

18. The “Talking Statue” of Thomas Edison in 1878

At the Exposition Universelle in Paris, Thomas Edison showcased his latest invention, the phonograph, which could record and reproduce sound. To demonstrate this marvel, he created a statue of himself that “spoke” using a hidden phonograph inside its chest. The exhibit was a technological triumph, but the sight of a famous inventor’s life-sized, talking effigy was profoundly eerie to many Victorians. The statue delivered a weird, almost magical, experience, a disembodied voice coming from a stationary figure, blurring the line between science and spectacle in an unsettling way.

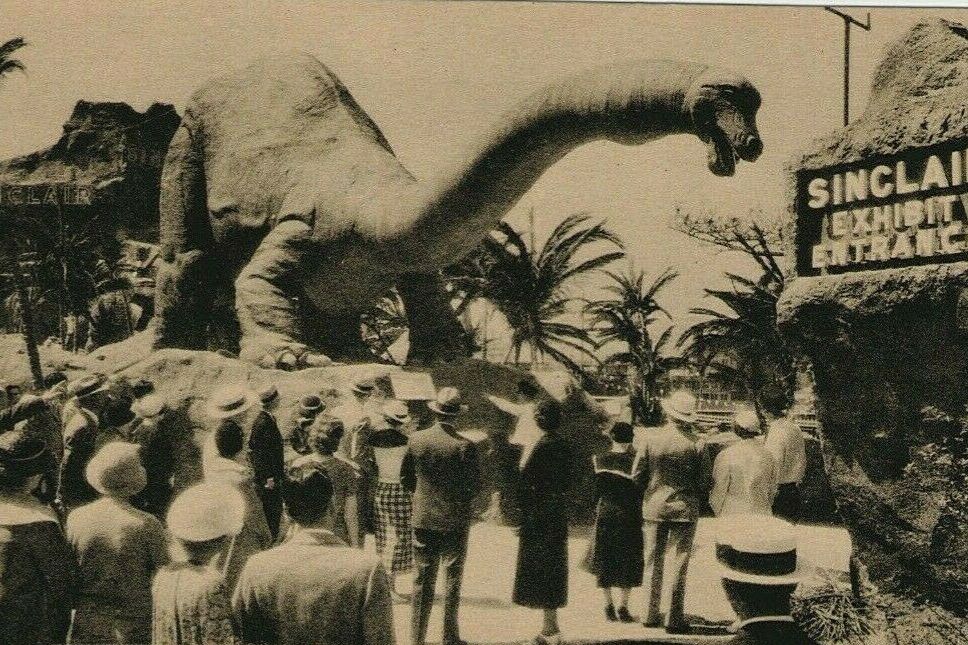

19. The Sinclair Dinosaur Exhibit in 1933

The Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago aimed to showcase scientific advancement, yet one of its most memorable features was decidedly prehistoric. The Sinclair Oil Company installed a hugely popular exhibit featuring life-sized, anatomically accurate models of various dinosaurs. While intended to illustrate the origins of oil (and promote their brand), the presence of these massive, terrifying replicas of extinct creatures stood in stark, weird contrast to the surrounding exhibits of sleek, modernist architecture and cutting-edge technology. It was a visually stunning, yet conceptually anachronistic, detour into the distant past within a fair dedicated entirely to the future.

20. The “Miracle of the Deep” Fish Tank in 1939

The 1939 New York World’s Fair featured a massive, 80-foot-long exhibit called “The Miracle of the Deep,” which was essentially a huge aquarium tank. It was an impressive feat of engineering to house and display such a complex marine ecosystem. However, the logistical nightmares, the challenge of keeping the diverse creatures alive, and the sheer volume of water made it an engineering spectacle that delivered little in terms of futuristic promise. It was an expensive, complicated way to show fish, proving that sometimes, even the most dedicated attempt to build a biological wonder can end up being just a very weirdly large and demanding fish tank.

These international showcases promised a pristine vision of “The World of Tomorrow,” yet their lasting legacy often includes these strange, unexpected, and sometimes unsettling moments.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.

This story 20 World’s Fairs That Promised the Future But Delivered the Weirdest Things was first published on Daily FETCH