The Silent Dangers Of The Deep

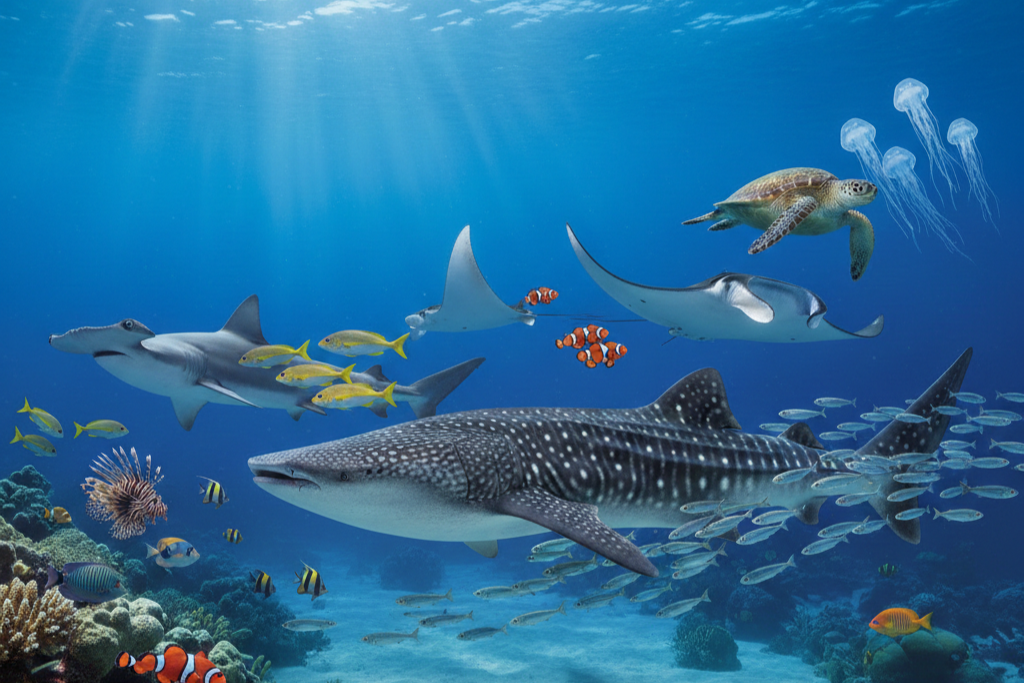

The ocean is a vast and majestic wilderness that covers the majority of our planet, yet it remains one of the most mysterious environments known to mankind. While we often view the sea as a place of serene beauty and recreational escape, it is also a realm governed by the raw laws of survival where some of the most sophisticated predators on Earth reside. Understanding these creatures is not merely about fostering a sense of fear but rather about developing a deep-seated respect for the delicate and often dangerous balance of marine ecosystems that exist beneath the waves.

Exploring the lethality of marine life allows us to appreciate the incredible evolutionary adaptations that have occurred over millions of years. From neurotoxic venoms to immense physical power, these animals have developed unique biological toolkits to thrive in a competitive underwater world. By learning about the world’s deadliest marine inhabitants, we gain a clearer perspective on our own place in nature and the importance of preserving these formidable species. This knowledge ensures that we can enjoy the wonders of the ocean while staying mindful of the hidden risks that accompany its breathtaking beauty.

Blue-Ringed Octopus

This tiny cephalopod might appear quite charming with its vibrant pulsating rings, but it is widely considered one of the most dangerous animals in the entire ocean. Growing no larger than a common golf ball, the blue-ringed octopus carries enough venom to end the lives of twenty-six adult humans within a matter of minutes. Its bite is often so painless that many victims do not even realise they have been targeted until the respiratory paralysis begins to take hold. There is currently no known antivenom for its potent neurotoxin called tetrodotoxin, which means the only treatment is immediate and prolonged artificial respiration until the poison eventually clears the body.

Found primarily in the tide pools and coral reefs of the Pacific and Indian Oceans, these creatures spend most of their time hiding in crevices or discarded shells. They only display their characteristic glowing blue rings when they feel threatened or provoked by an intruder. Because they are so small and well-camouflaged, many accidents happen when curious swimmers or divers inadvertently touch them while exploring the seabed. It is a sobering reminder that in the marine world, the most unassuming and beautiful creatures are often the ones that possess the most lethal capabilities for self-defence against any perceived threats.

Box Jellyfish

The box jellyfish is frequently cited as the most venomous marine animal on the planet because its stings are incredibly painful and often prove fatal to humans. These ethereal invertebrates possess long trailing tentacles that are covered in thousands of specialised stinging cells known as nematocysts, which fire like tiny harpoons upon contact. The venom is designed to attack the heart, nervous system, and skin cells simultaneously, leading to a state of intense shock or cardiac arrest before a victim can even reach the shore. Their bodies are almost entirely transparent, which makes them nearly impossible for swimmers to spot in the water until it is far too late.

Unlike most jellyfish that simply drift with the currents, the box jellyfish is a surprisingly active swimmer that can direct its movement and even possesses sets of true eyes to navigate. They are most commonly found in the coastal waters of Northern Australia and throughout the Indo-Pacific region, particularly during the warmer months when they move closer to the beaches. Safety nets and protective suits are common sights in these areas because a single encounter can be life-threatening within seconds. It is truly remarkable how such a delicate and translucent organism can exert such total dominance over its environment through sheer chemical potency and sophisticated biological engineering.

Great White Shark

The great white shark remains the ultimate apex predator of the seas and occupies a significant place in the human psyche as a symbol of maritime danger. These massive cartilaginous fish can grow to lengths exceeding six metres and are equipped with rows of serrated teeth designed for tearing through the tough blubber of seals and sea lions. While they do not specifically hunt humans, their investigative bites are so powerful that they can cause catastrophic blood loss and internal trauma. They possess an extraordinary sense of smell and the ability to detect electromagnetic fields, which allows them to track prey over vast distances with incredible precision.

Beyond their physical prowess, great white sharks are highly intelligent hunters that often use the element of surprise by attacking from below with immense speed. They are found in cool coastal waters across the globe, including areas off the coasts of South Africa, California, and Australia. Despite their fearsome reputation, they are a vulnerable species that plays a crucial role in maintaining the health of the oceans by regulating prey populations. Protecting these magnificent creatures is essential for ecological stability, even though we must remain cautious and respectful whenever we enter their natural hunting grounds during our own aquatic adventures.

Reef Stonefish

The reef stonefish is a master of disguise that perfectly mimics the appearance of an encrusted rock or a piece of coral on the ocean floor. This incredible camouflage makes it one of the most dangerous creatures for unsuspecting divers and waders who might accidentally step on its dorsal fins. Along its back, the stonefish carries thirteen sharp spines that act like hypodermic needles, injecting a highly toxic venom that causes excruciating pain and tissue necrosis. The agony is often described as being so intense that victims have been known to beg for the affected limb to be removed to escape the sensation.

These sedentary fish are found throughout the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific and prefer to sit perfectly still while waiting for small fish or shrimp to swim past. Because they can survive out of the water for several hours, they pose a significant risk on beaches during low tide where they blend seamlessly into the damp sand or rocks. Medical intervention is required immediately after a sting because the venom can lead to heart failure and paralysis if left untreated. It is a brilliant yet terrifying example of how evolution has prioritised concealment and chemical warfare to ensure survival in the competitive environment of a crowded coral reef.

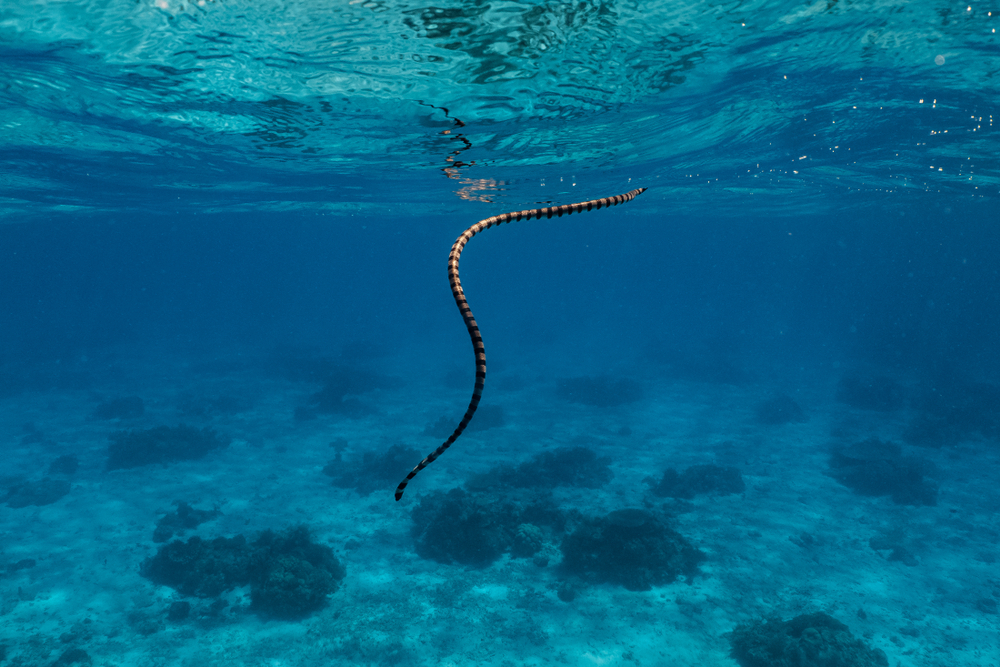

Belcher’s Sea Snake

While sea snakes are generally shy and reluctant to bite, the Belcher’s sea snake possesses a venom so concentrated that a few milligrams could theoretically kill over a thousand people. These aquatic reptiles spend their entire lives in the water and are exceptionally well-adapted to the marine environment with paddle-like tails and the ability to stay submerged for long periods. They are most commonly encountered by fishermen who find them tangled in nets or by divers exploring the warm reefs of the Indian Ocean. Fortunately, they have a very gentle temperament and rarely inject a full dose of venom when they do bite in self-defence.

The primary danger arises from the fact that their venom is a potent neurotoxin that disrupts the communication between the brain and the muscles. This leads to a gradual onset of paralysis and respiratory failure, which can be particularly deceptive because the initial bite site might not show much swelling or pain. Scientists study their venom for potential medical breakthroughs, but for the average person, maintaining a respectful distance is the best course of action. They serve as a vital link in the marine food chain and remind us that even the most lethal inhabitants of the ocean prefer to avoid conflict with humans whenever it is possible.

Red Lionfish

The red lionfish is as beautiful as it is dangerous, featuring striking stripes and elegant, fan-like fins that conceal a series of venomous spines. Originally native to the Indo-Pacific, they have become a highly invasive and problematic species in the Atlantic and Caribbean waters where they have no natural predators. Their venom is delivered through the needle-like spines on their back and underside, causing extreme pain, sweating, and even respiratory distress in humans. While their stings are rarely fatal to healthy adults, the sheer intensity of the pain makes them a major concern for divers and coastal residents alike.

These predators are known for their voracious appetites and their ability to consume vast quantities of native fish, which can devastate local reef ecosystems. They use their elaborate fins to corner prey before striking with lightning speed, making them highly effective hunters in almost any environment they inhabit. Efforts to control their populations often involve organised culls and encouraging people to consume them as a delicacy, provided the spines are carefully removed. The lionfish represents a unique challenge where a single species can pose a direct threat to human safety while simultaneously causing widespread ecological damage to some of the world’s most cherished underwater habitats.

Geographic Cone Snail

The geographic cone snail may look like a beautiful collectible shell, but inside dwells a predator with one of the most complex and deadly chemical cocktails in nature. Often referred to as the cigarette snail because it is said that a victim has only enough time to smoke one cigarette before dying, its venom contains hundreds of different toxins. It hunts by extending a flexible proboscis that fires a venom-filled harpoon into its prey, instantly paralysing fish so they can be consumed whole. There is no antivenom for a cone snail sting, and treatment focuses solely on keeping the victim alive until the toxins wear off.

Collectors are often drawn to the intricate patterns on their shells, but picking one up can be a fatal mistake as the snail can strike from any part of its opening. They are primarily found in the tropical reefs of the Indo-Pacific where they hide under the sand during the day and hunt at night. Interestingly, the very toxins that make them so deadly are now being researched for use in powerful painkillers that are hundreds of times more effective than morphine. This highlights the fascinating duality of marine life where a creature that can end a life so quickly may also hold the key to saving many others through medicine.

Flower Urchin

The flower urchin is frequently cited by the Guinness World Records as the most dangerous sea urchin in the world because of its unique stinging mechanism. Unlike other urchins that rely on long sharp spines, the flower urchin is covered in tiny, flower-like appendages called pedicellariae that act like miniature biting jaws. When touched, these structures grab onto the skin and inject a potent venom that causes severe pain, muscular paralysis, and respiratory problems. The beauty of its floral appearance is a deceptive facade that hides a highly effective defensive system capable of incapacitating even large intruders who get too close.

This species is most common in the Indo-West Pacific region and prefers to inhabit seagrass beds and coral reefs where it can blend in with the surrounding flora. Because they are often partially buried or covered in debris, they are easy to miss, leading to accidental contact by swimmers and divers. The venom is particularly dangerous because it can cause a person to lose control of their muscles while still underwater, which significantly increases the risk of drowning. Respecting the “look but don’t touch” rule is vital when exploring these environments because even the most stationary and pretty organisms can have devastating consequences for those who are careless.

Tiger Shark

Known as the “garbage can of the sea,” the tiger shark is a massive predator that is famous for its willingness to eat almost anything it encounters. They are the second most likely shark to be involved in incidents with humans, largely because they frequent shallow coastal waters and have a very indiscriminate palate. With their distinctive dark stripes that fade as they age, these sharks can grow up to five metres in length and possess incredibly strong jaws capable of crushing the shells of sea turtles. They are highly migratory and can be found in tropical and subtropical waters all around the world throughout the year.

Tiger sharks are particularly dangerous because they are curious and bold, often investigating anything that floats on the surface including surfboards and small boats. Their nocturnal hunting habits and preference for murky water near river mouths increase the likelihood of accidental encounters with humans. However, like all sharks, they are a vital part of the ocean’s health and are currently facing threats from overfishing and habitat loss. Understanding their behaviour and respecting their territory is the best way for humans to coexist with these powerful apex predators that have patrolled the oceans for millions of years with remarkable efficiency and evolutionary success.

Saltwater Crocodile

The saltwater crocodile is the largest living reptile on the planet and is a formidable predator that effortlessly bridges the gap between land and sea. These prehistoric giants can grow to lengths of over six metres and are known for their incredible strength and aggressive territorial nature. While they primarily inhabit brackish estuaries and mangrove swamps, they are excellent swimmers and are frequently spotted far out at sea or patrolling coastal beaches. They use a “sit and wait” strategy, remaining perfectly still just below the surface before launching a lightning-fast attack on anything that comes too close to the water’s edge.

Encounters with saltwater crocodiles are often fatal because of their immense bite force and the “death roll” technique they use to drown and dismember their prey. They are found across Southeast Asia and Northern Australia, where they are treated with the utmost caution by locals and tourists alike. Their ability to survive in both fresh and salt water makes them a unique threat that requires constant vigilance in their known habitats. Despite their fearsome reputation, they are ancient survivors that have remained virtually unchanged for millions of years, representing a direct link to the age of the dinosaurs and the raw power of the natural world.

Portuguese Man O’ War

While it is often mistaken for a common jellyfish, the Portuguese man o’ war is actually a siphonophore which consists of a colony of specialized organisms working together as one. This strange and beautiful creature is easily identified by its bright blue or purple gas-filled bladder that floats on the surface like a miniature sail. Beneath the waves, it trails incredibly long tentacles that can reach lengths of up to fifty metres and are packed with potent stinging cells. These venomous filaments are designed to paralyze small fish and crustaceans instantly, but they can also deliver an excruciatingly painful sting to any human swimmer who accidentally brushes against them in the water.

The venom of a man o’ war is a complex mixture of proteins that causes severe localized pain, whip-like red welts on the skin, and sometimes systemic reactions such as fever or shock. Because they are at the mercy of the winds and ocean currents, they often wash up on beaches in large numbers during certain times of the year. Even after being stranded on the sand for several days, their tentacles remain active and can still deliver a powerful sting to unsuspecting beachgoers or curious children. It is a fascinating example of how a communal organism can function as a singular and highly effective predator that relies on the natural elements to travel across the vast global oceans.

Bull Shark

The bull shark is widely considered the most dangerous shark to humans because of its aggressive nature and its unique ability to thrive in both salt and fresh water. These robust predators possess a high tolerance for low salinity, allowing them to swim hundreds of miles up rivers like the Amazon or the Mississippi into areas where people do not expect to find sharks. They are stout and powerful fish with a blunt snout and a tendency to headbutt their prey before attacking, which is how they earned their common name. Their diet is incredibly varied, ranging from fish and dolphins to other smaller sharks, making them highly opportunistic hunters in any environment.

Because they frequent shallow coastal waters, estuaries, and river mouths where people swim and fish, the likelihood of an encounter with a bull shark is significantly higher than with other species. They are known for their unpredictable temperament and can become highly territorial if they feel their space is being encroached upon by humans. While they are often vilified in popular media, they are an essential component of the aquatic food web and help maintain the biological diversity of coastal ecosystems. Understanding their migratory patterns and avoiding murky water at dawn or dusk is a vital safety measure for anyone living or holidaying in regions where these adaptable and formidable predators are known to roam.

Maricopa Harvester Ant

The Maricopa harvester ant is a terrestrial insect that is often included in marine-adjacent discussions because it inhabits coastal plains and sandy regions near the sea. It holds the distinction of having the most toxic venom of any known insect, which is a powerful cocktail of proteins and enzymes designed to protect the colony. A single sting from one of these ants is said to be as painful as a hornet, but the real danger lies in their tendency to attack in large numbers when their nest is disturbed. They latch onto their victim with their mandibles and sting repeatedly, which can lead to severe allergic reactions or even death in smaller animals and vulnerable humans.

These ants are most commonly found in the arid and semi-arid regions of the Southwestern United States and Mexico, often near the coastline where they forage for seeds and organic matter. They play a vital role in their local environment by dispersing seeds and aerating the soil, but they are treated with great respect by anyone who knows of their chemical potency. While they do not actively hunt humans, their defensive instincts are incredibly sharp, and a single colony can contain thousands of individuals ready to protect their queen. It serves as a stark reminder that some of the most lethal toxins on our planet can be found in the smallest of creatures living just above the high-tide mark.

Irukandji Jellyfish

The Irukandji is a tiny and nearly invisible jellyfish that is responsible for a terrifying condition known as Irukandji syndrome which can be life-threatening to humans. Measuring only about one cubic centimetre in size, this translucent creature is so small that it can easily pass through most protective sea nets designed to keep larger jellyfish away from swimming beaches. Its venom is exceptionally powerful, and while the initial sting might feel like a minor mosquito bite, the systemic symptoms that follow are often described as a sense of impending doom. Victims experience severe muscle cramps, excruciating back pain, vomiting, and dangerously high blood pressure that requires immediate and intensive medical care.

These lethal invertebrates are primarily found in the warm waters of Northern Australia, but their range appears to be expanding due to the gradual warming of the global oceans. Because they are so difficult to see, divers and swimmers often have no idea they have been stung until the agonizing symptoms begin to manifest about thirty minutes later. There is no specific antivenom for Irukandji syndrome, so doctors must focus on managing the pain and stabilizing the patient’s vital signs until the toxins eventually leave the body. It is a humbling example of how a creature that is almost entirely composed of water and is smaller than a fingernail can bring a healthy adult to a state of total physical collapse.

Moray Eel

The moray eel is a serpentine predator that lives in the crevices of coral reefs and rocky shorelines, where it waits for unsuspecting prey to swim within reach of its jaws. While they are not typically aggressive toward humans, they are highly territorial and will defend their burrows with a lightning-fast and powerful bite if they feel threatened. Moray eels possess a unique second set of jaws located in their throat, known as pharyngeal jaws, which reach forward to grab prey and pull it deep into their gullet. This dual-jaw system makes their grip incredibly strong and difficult to release once they have latched onto a hand or a foot of a diver.

The danger of a moray eel bite is compounded by the fact that their mouths are home to a wide variety of bacteria that can cause severe infections in human tissue. Additionally, some species of moray eels can be toxic if consumed, as they accumulate ciguatoxins through their diet of reef fish, leading to serious illness in humans. Most incidents involving morays occur when divers attempt to hand-feed them or accidentally put their hands into a hole where an eel is hiding. They are beautiful and misunderstood creatures that perform a vital service by keeping reef populations in check, but they demand a high level of caution and respect from anyone exploring their underwater world.

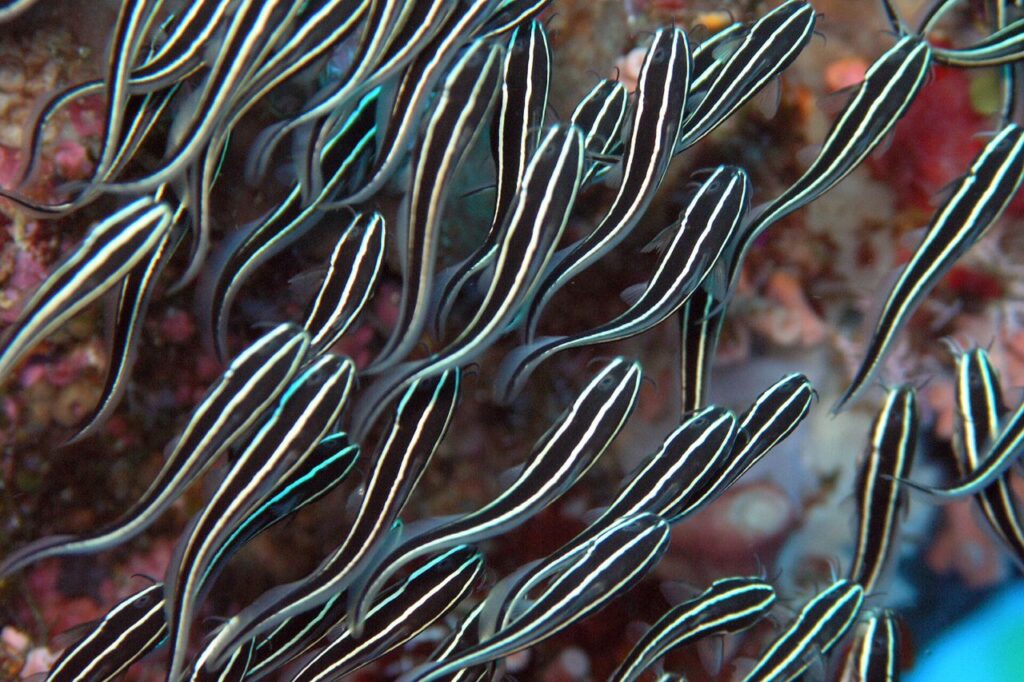

Striped Eel Catfish

The striped eel catfish is the only species of catfish that is commonly found living in coral reef environments, and it is a creature that should never be handled without extreme care. These fish are easily recognized by the striking white stripes that run along their dark bodies and the sensitive barbels around their mouths that help them find food in the sand. While they may look relatively harmless as they swim in tight, ball-like schools, they possess highly venomous spines on their dorsal and pectoral fins. A puncture from one of these spines can cause intense pain, significant swelling, and in some rare cases, can even be fatal to humans if the venom enters the bloodstream.

These social fish are frequently found in the Indo-Pacific region and are often spotted by snorkelers in shallow waters or among seagrass beds where they forage for small invertebrates. The venom they carry is a potent protein-based toxin that acts as a highly effective deterrent against larger predators like sharks or groupers. Because they move in large groups, an accidental encounter can result in multiple stings, which significantly increases the severity of the reaction and the risk of complications. They are a perfect example of how evolution has provided even relatively small fish with sophisticated chemical weapons to ensure their survival in the highly competitive and dangerous environment of a tropical coral reef.

Barracuda

The great barracuda is a sleek and silvery predator that is often referred to as the “tiger of the sea” because of its fearsome appearance and lightning-fast strike speed. These fish can grow to nearly two metres in length and are equipped with a mouth full of long, razor-sharp teeth that are designed for slicing through the flesh of their prey. While they are generally curious and will often follow divers at a distance, they can become aggressive if they are provoked or if they mistake a shiny object for a shimmering fish. Their ability to accelerate from a standstill to high speeds makes them one of the most efficient and intimidating hunters in the open ocean.

Most recorded incidents involving barracudas and humans are the result of poor visibility or the presence of shiny jewellery, which the fish can mistake for the scales of a small prey animal. Their bite can cause deep lacerations and significant nerve damage, requiring immediate surgical attention to prevent long-term disability or infection. In addition to the risk of physical injury, the meat of larger barracudas can be highly toxic due to the accumulation of ciguatera toxins, which can cause severe neurological problems if eaten by humans. They are magnificent examples of marine engineering and predatory efficiency, reminding us that speed and sharp teeth are often the most effective tools for survival in the vast blue wilderness.

Stingray

Stingrays are generally docile and graceful creatures that glide along the seabed, but they possess a formidable defensive weapon in the form of a venomous, serrated barb located at the base of their tail. Most injuries to humans occur when a person inadvertently steps on a ray that is buried in the sand, triggering a defensive reflex where the tail strikes upward like a scorpion. The barb can penetrate deep into flesh and even bone, injecting a venom that causes immediate and excruciating pain, tissue death, and a high risk of infection. While fatalities are rare, a sting to a vital organ can be catastrophic, as seen in several high-profile incidents over the years.

These cartilaginous fish are found in coastal waters all over the world and are a common sight in shallow areas where people like to swim and wade. To avoid accidental stings, many beachgoers practice the “stingray shuffle,” which involves sliding one’s feet through the sand to alert any hidden rays to their presence. Despite their potential for harm, stingrays are intelligent and curious animals that play a significant role in the health of the seabed by aerating the substrate as they hunt for food. They are a beloved sight for many divers and snorkelers, but they serve as a constant reminder that even the most peaceful-looking animals have the capacity to defend themselves with lethal precision if they are startled.

Flower Hat Jellyfish

The flower hat jellyfish is one of the most visually stunning invertebrates in the ocean, featuring a translucent bell adorned with vibrant, multi-coloured tentacles that resemble a floral arrangement. However, this beauty is highly deceptive, as the sting from a flower hat jellyfish is known to be incredibly painful and can lead to a severe skin rash and systemic illness. They are primarily found in the coastal waters of Japan, Brazil, and Argentina, where they spend most of their time sitting on the seabed rather than swimming in the water column. This sedentary lifestyle makes them a unique threat to anyone who might accidentally touch them while exploring the ocean floor.

The venom of the flower hat jellyfish contains toxins that can cause a localized reaction, but in some individuals, it can also lead to respiratory distress and more serious cardiovascular issues. Because they are not very common and have a limited geographic range, they are often overlooked in discussions about dangerous marine life, yet they remain a significant hazard in the regions where they reside. Their striking appearance often attracts the attention of curious divers, but the “look but don’t touch” rule is especially important when dealing with such a potent and beautiful organism. They represent the incredible diversity of the jellyfish family and the various ways that these ancient creatures have developed to protect themselves from the many threats found in the sea.

Crown-of-Thorns Starfish

The crown-of-thorns starfish is a large and intimidating species that is covered in long, venomous spines that can reach up to five centimetres in length. Unlike most starfish that have five arms, this predator can have up to twenty-one arms and can grow to be nearly half a metre in diameter. If a human accidentally brushes against or steps on one of these starfish, the brittle spines can break off in the skin, causing intense pain, nausea, and persistent swelling that can last for weeks. They are notorious for their ability to devastate coral reefs, as they feed by extruding their stomachs over the coral and digesting the living polyps, leaving behind a white skeleton of dead calcium carbonate.

These starfish are found throughout the Indo-Pacific region and are currently considered a major threat to the health of the Great Barrier Reef due to frequent population outbreaks. During these outbreaks, thousands of crown-of-thorns starfish can descend upon a reef, consuming vast areas of coral in a very short period and significantly altering the ecosystem. Conservationists often go to great lengths to control their numbers, including the use of specialized robots or manual injections of vinegar to culls them safely. They are a stark example of how a single species can become a deadly threat to an entire underwater habitat when the natural balance of predators and prey is disrupted by human activity or environmental changes.

The fragility of our oceans is often underscored by our heavy reliance on singular sources of resources and the ecological impact of human interference on these delicate habitats.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.