These are historical facts I bet you didn’t realize till you read this story.

Don McLean’s “American Pie” is more than a song; it’s a lyrical time machine, an epic 8-and-a-half-minute ballad that became a cultural phenomenon. Released in 1971, it uses cryptic, poetic imagery to trace the arc of American culture from the innocent 1950s rock-and-roll era to the turbulent, fragmented close of the 1960s. Many lines have sparked debates for decades, but together they form a powerful, nostalgic tapestry that captured the sense of a generation losing its way.

1. The Day the Music Died

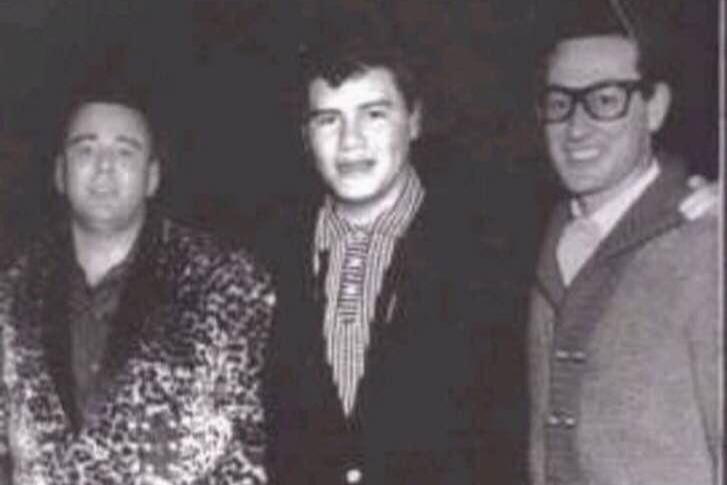

The literal heartbeat of the song is the 1959 plane crash near Clear Lake, Iowa, that killed rock-and-roll pioneers Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and J.P. “The Big Bopper” Richardson. For Don McLean, who delivered newspapers in his youth, reading about the tragedy in the headlines was a profoundly formative moment, as he’s explicitly stated that this event is the song’s primary narrative starting point. It’s referenced immediately in the opening stanza when he sings, “A long, long time ago I can still remember how that music used to make me smile / And I knew if I had my chance that I could make those people dance / And maybe they’d be happy for a while.” This event didn’t just end the lives of three musicians; it symbolized for McLean and many fans the end of rock’s youthful innocence, ushering in a more complex and often darker musical and cultural landscape in the decade that followed.

2. Jukebox Saturdays

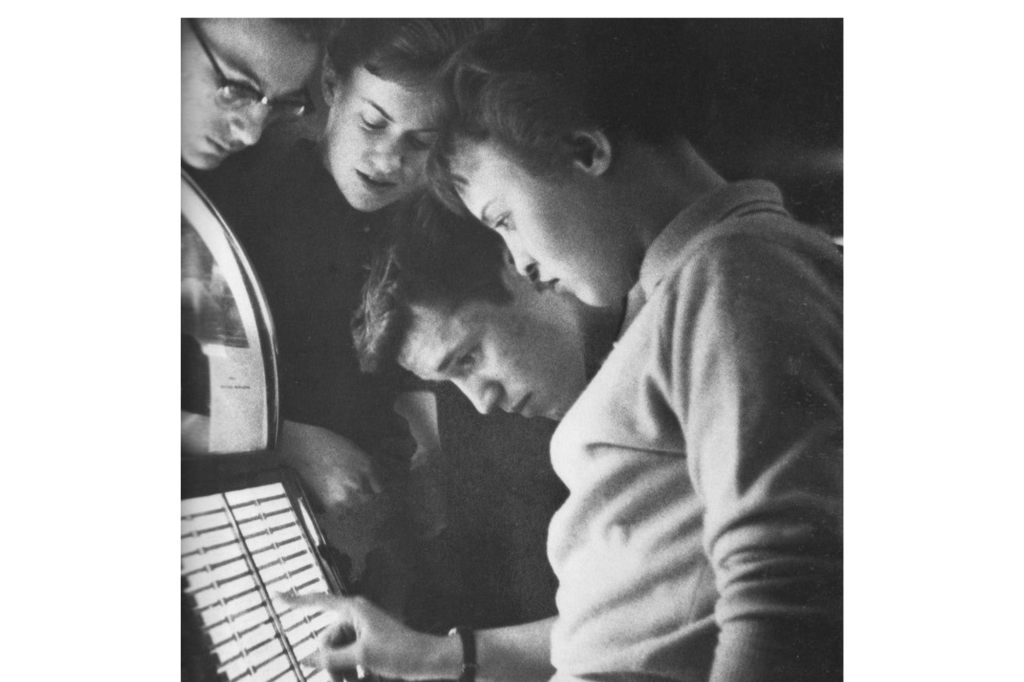

McLean paints a nostalgic scene of teens gathered in local diners and soda shops, referencing the jukebox as a central social tool of the 1950s. The song recalls a time before personalized playlists and streaming, when music was a communal experience, chosen one coin at a time. The glowing, colorful jukeboxes of the era, such as the iconic Wurlitzer and Seeburg models, were monuments of youthful leisure, filling the air with the latest hits by artists like Elvis and Chuck Berry. This image of shared musical joy in a public space, like when McLean mentions “playing rock and roll records” and “the music died,” is a potent symbol of simplicity and pre-Sixties cultural unity that the song suggests was lost.

3. Sock Hops and School Dances

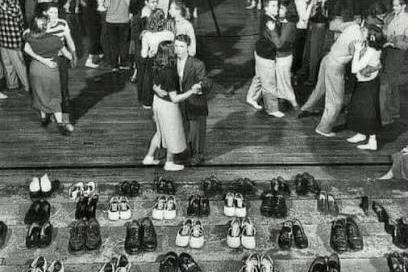

The lyrics evoke the quintessential high school social scene of the 1950s: the sock hop. These casual, often afternoon dances were frequently held in school gyms or cafeterias, and attendees were encouraged to remove their shoes, hence “sock hop”, to protect the polished wooden floors. This detail perfectly captures a time of wholesome, chaperoned youth culture. The music, a blend of early rock, rhythm-and-blues, and Doo-Wop, provided the soundtrack for innocent flirting and small-town gatherings. By referencing this activity, McLean sets a clear baseline for the pure, uncomplicated youth culture that he contrasts so sharply with the later turmoil of the 1960s.

4. Good Old Boys and Drive-In Diners

The “good old boys” referenced in the song are a clear nod to the easygoing, simpler youth culture of the pre-Beatles 1950s. This term, often used regionally, signifies a sense of camaraderie and small-town American life, a time when hanging out meant cruising in cars and gathering at drive-in diners. These diners, like the famous ones that popularized car-hop service, were essential social hubs where teenagers shared milkshakes, sang along to the car radio, and simply were. This imagery helps to firmly root the song’s beginning in an idealized, almost cinematic version of postwar America, underscoring the stark difference between the peace of this era and the coming turbulence.

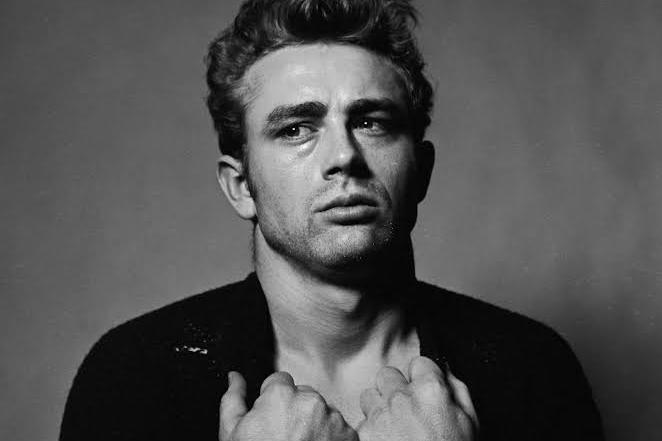

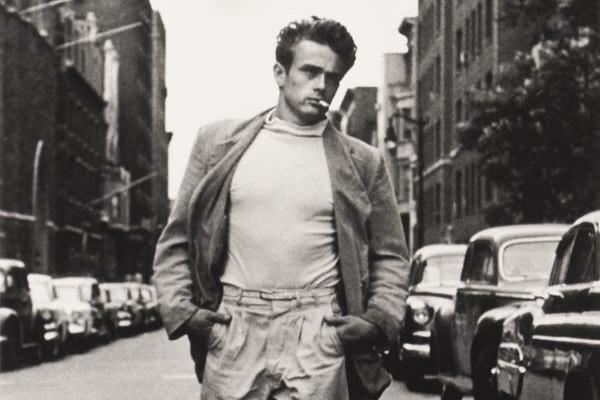

5. James Dean Rebellion

While never explicitly named, the spirit of youthful rebellion McLean describes, the kind that was brewing beneath the surface of the Eisenhower years, is deeply connected to the cultural figure of James Dean. Dean’s iconic roles in films like Rebel Without a Cause (1955) and East of Eden crystallized the image of the misunderstood, sensitive, and profoundly restless young man. This new, post-war generation yearned for an identity separate from their parents, and rock-and-roll was their voice. Dean’s untimely death in 1955 only cemented his status as a martyr for this cause, making the unspoken presence of his rebellious spirit a key element in the song’s nostalgic lament for lost potential and innocence.

6. Elvis Presley

The King of Rock ’n’ Roll, Elvis Presley, is a towering figure whose shadow falls over the song’s narrative of musical transition. The line “the King and Queen” is widely interpreted as a reference to Elvis and perhaps his eventual wife, Priscilla, or to Elvis’s unparalleled status. Elvis was a revolutionary cultural force, blending gospel, country, and rhythm and blues to create an electric, controversial, and utterly defining sound of the 1950s. However, the song’s narrative feels like it happens after Elvis’s most rebellious phase; his 1958 Army induction and subsequent shift toward family-friendly Hollywood films marked a cultural cooling of the initial rock-and-roll flame. Therefore, his “ghost” in the song represents not just the genre’s birth but also its subsequent domestication, contributing to the feeling that the “music died.”

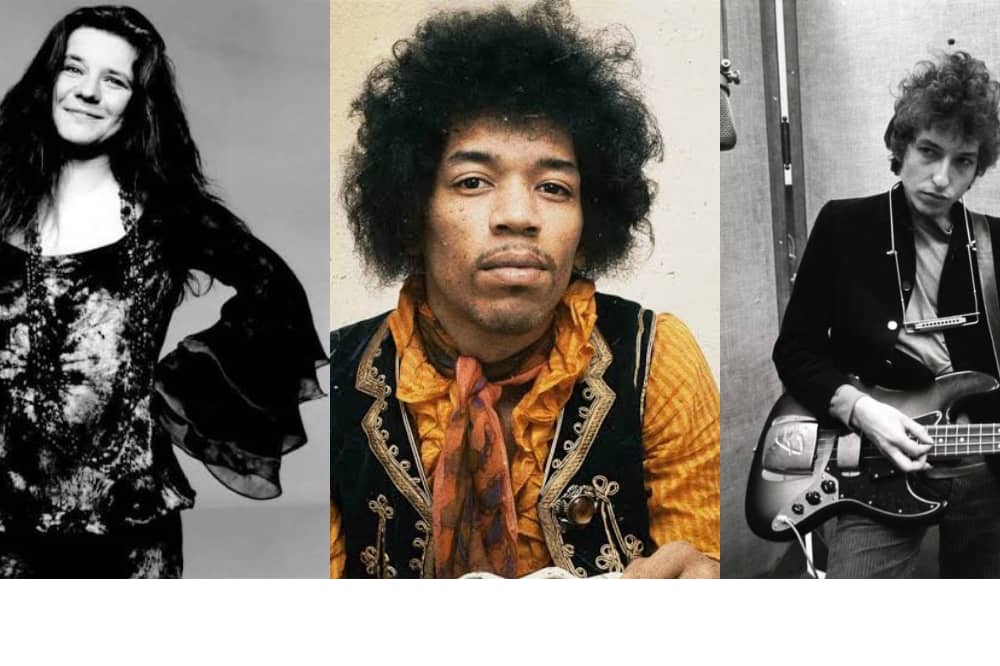

7. Bob Dylan as “The Jester”

The most famous of American Pie’s enigmatic figures is the “jester” who sings “in a borrowed coat,” a widely accepted stand-in for Bob Dylan. Dylan’s rise in the early 1960s marked a profound shift in popular music: he traded the carefree dance rhythms of early rock for deeply introspective, folk-driven poetry and protest songs. His acoustic sound and serious lyrical themes were a stark contrast to the bubblegum pop that followed the initial rock explosion. The “borrowed coat” often points to his early days of imitating Woody Guthrie and other folk figures, or simply his bohemian style. The jester’s arrival represents the moment when music stopped being solely about fun and dancing and began to be a tool for cultural commentary and political critique, fundamentally reshaping the industry.

8. The Beatles and Sgt. Pepper

When McLean sings about “The Sergeants played a marching tune,” he makes a direct, unmistakable reference to The Beatles and their groundbreaking 1967 album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. This album was a watershed moment, transforming pop music from simple singles into complex, conceptual studio art. The “marching tune” of the title track is what kicked off an era of psychedelic exploration and studio experimentation. The Beatles’ arrival in America and their subsequent cultural dominance were instrumental in replacing the older folk and early rock traditions, signifying a new, wildly creative, and decidedly British-led musical era that pushed the American-born rock narrative into a new phase.

9. The Rolling Stones

The lyrics “And the Satan laughing with delight / As the flames leaped high into the night” are generally interpreted as a nod to The Rolling Stones and their edgier, often darker, and more sexually charged take on rock music. Where The Beatles were initially seen as clean-cut pop, The Stones cultivated an image of dangerous, rebellious anti-heroes, epitomized by frontman Mick Jagger’s swaggering stage presence. Their music, rooted deeply in the blues, had a primal, almost menacing energy, and their later album, Their Satanic Majesties Request, cemented this association in the public mind. They represent the darker, more transgressive undercurrent of the 1960s, a stark contrast to the idealism of the early decade.

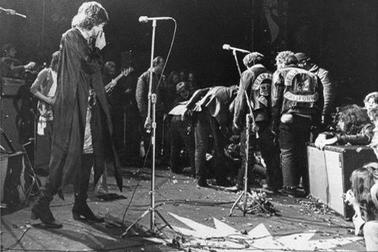

10. Altamont Free Concert (1969)

The chilling reference to the “flames leaped high into the night” and a violent “man shot down” is a direct, tragic allusion to the infamous Altamont Free Concert in December 1969. Intended to be a “West Coast Woodstock,” the Rolling Stones-headlined event was instead marred by chaos and violence, famously culminating in the stabbing death of a concertgoer, Meredith Hunter, by a member of the Hells Angels, who had been hired as security. Altamont is often cited by historians and cultural critics as the symbolic death knell for the 1960s counterculture’s dream of peace and love. It was a widely documented moment where the era’s idealism was brutally confronted by real-world violence, permanently darkening the collective memory of the decade.

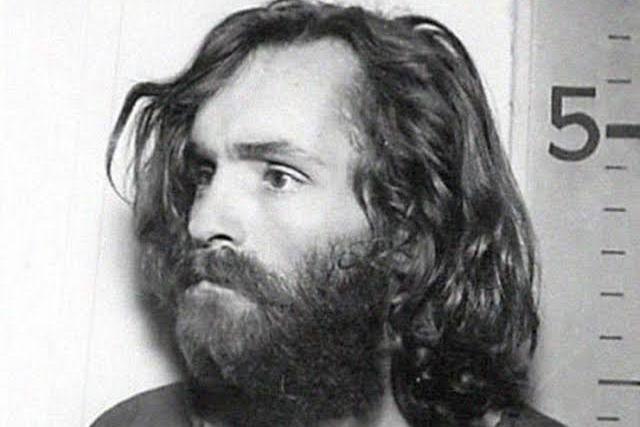

11. Charles Manson Shadows

The eerie line “helter skelter in a summer swelter” is a chilling nod to Charles Manson and the murders committed by his “Family” in the summer of 1969. Manson famously distorted and misinterpreted The Beatles’ song “Helter Skelter” from The White Album, believing it contained coded messages about an impending race war. He and his followers scrawled the song’s title in blood at a murder scene. McLean’s inclusion of this phrase uses a seemingly innocent pop song to signal the complete corruption of the era’s hopeful ideals. It is perhaps the most pointed reference in the song to how the 1960s dream of peace and utopian community was tragically haunted and ultimately shattered by real-world violence, paranoia, and madness.

12. Janis Joplin, the Girl Who Sang the Blues

McLean’s “girl who sang the blues” is widely accepted to be a poignant reference to Janis Joplin. Joplin’s electrifying, raw, and deeply soulful voice made her the undisputed female superstar of the late 1960s rock scene, capturing a powerful blend of vulnerability and explosive energy. She was an icon of the hippie movement and an artist who fully embodied the rock-and-roll lifestyle. Her tragic, untimely death from an overdose in October 1970, following the deaths of Jimi Hendrix and others, became another profound cultural moment of loss. For McLean, her passing symbolized yet another great talent lost to the era’s excesses, contributing to the song’s narrative that the music, and the hope it represented, was continually dying.

13. Woodstock, 1969

In direct contrast to the tragic chaos of Altamont, the massive, three-day Woodstock Festival in August 1969 remains the quintessential symbol of the 1960s’ peak idealism. McLean’s lyrics implicitly reference the event’s scope and impact. Half a million young people gathered in a field in upstate New York for “three days of peace and music,” creating a globally celebrated image of countercultural unity. Despite logistical chaos, the pervasive atmosphere of communal harmony and artistic freedom solidified Woodstock’s place in history as a temporary utopia. By recalling the high point of this idealism, McLean enhances the subsequent sense of betrayal and fragmentation that defined the end of the decade.

14. Vietnam Era Divide

Running beneath nearly all the song’s verses is the unrelenting, divisive shadow of the Vietnam War. The conflict deeply fractured American society, pitting generations against each other and sparking a massive anti-war movement that fundamentally changed politics and culture. McLean’s lyrics about “war clouds” and the sense of a nation coming apart at the seams are a clear reflection of this. Music, particularly folk and protest songs, became a critical tool for both expressing dissent and seeking escape from the painful reality of the conflict. The war’s pervasive influence is a key reason why the simple, unified joy of 1950s rock-and-roll could not survive, leading to the fragmented, politically charged sound of the late 1960s.

15. Assassinations of the 1960s

Though the song never explicitly names any political figures, the overall sense of pervasive grief, lost optimism, and a nation’s “loss of innocence” undeniably mirrors the devastating political assassinations of the decade. The murders of President John F. Kennedy (1963), Malcolm X (1965), Martin Luther King Jr. (1968), and Senator Robert Kennedy (1968) delivered continuous, crushing blows to the American psyche. These tragedies systematically dismantled the bright, idealistic hopes of the New Frontier and Civil Rights movements. The profound cultural shift McLean chronicles, from the cheerful “happy for a while” music to a dark, complex lament, is inextricably linked to the national heartbreak caused by these pivotal losses.

16. The Counterculture Shift

McLean’s lyrics trace the seismic cultural shift from the “buttoned-up,” conservative 1950s to the radically expressive late 1960s counterculture. This movement was defined by its wholesale rejection of traditional American values, promoting long hair, non-conformity, drug use, and an ethos of “free love.” The collision of these two worldviews is a central theme in the song’s narrative about a generation that broke away from its parents’ ideals. The rise of psychedelic rock and protest music served as the soundtrack to this movement, marking a clear and irreversible break from the more innocent, commercialized music of the previous decade. The song’s sadness is largely about this cultural rift and the unbridgeable gap it created in the American experience.

17. The End of an Era

By the time McLean wrote and released American Pie in 1971, the music landscape was fundamentally changed, prompting his deep sense of lament. The Beatles had officially broken up in 1970; Bob Dylan had retreated from the public eye and shifted his sound to country-rock; Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were dead; and the idealism of the counterculture had been fractured by events like Altamont. The song itself captures the cultural fatigue that set in as the era’s major unifying forces dissolved. McLean felt the unifying dream of early rock ’n’ roll was truly “gone forever,” replaced by a confusing, fragmented, and often cynical music industry searching for its next identity.

18. McLean’s Farewell to Innocence

Ultimately, beyond all the historical references, American Pie serves as Don McLean’s intensely personal farewell to his own youth and the formative innocence of his early life. He was a young man when he read the newspaper headline about Buddy Holly’s death, an event that became his personal marker for the end of a simple, happy time. The song is the work of an adult looking back on the optimism of his childhood through the lens of a chaotic adulthood. By weaving his own grief and nostalgia with collective national memories, McLean turns a private journal entry into a universal anthem, allowing every listener to find their own moment of lost innocence in his expansive, poetic verses.

What references to the 1960s resonated most with you when you first heard the song?

This story 18 Nostalgic References Hidden in Don McLean’s American Pie was first published on Daily FETCH