1. Olivia de Havilland v. Warner Bros. Pictures

In 1944, actress Olivia de Havilland sued her studio, Warner Bros., seeking to be released from her contract. Studio contracts at the time typically ran for a fixed number of years, but the studios would often suspend actors who refused roles, adding the suspension time onto the end of the contract. This meant a seven-year contract could stretch far longer, essentially creating a form of indentured servitude. De Havilland won her case, with the California Court of Appeal ruling that a contract for personal services could not legally extend beyond seven calendar years, regardless of time suspended. The victory gave actors significantly more freedom and leverage in negotiations, making it the bedrock of performer rights in Hollywood.

2. Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc

Known as the “Betamax case,” this 1984 Supreme Court decision legalized the recording of television programs for private, noncommercial use, a practice called “time-shifting.” Universal and Disney had sued Sony, the manufacturer of the Betamax VCR, claiming that by selling the device, Sony was contributing to mass copyright infringement. The court’s majority opinion established the principle that a product with “substantial non-infringing uses,” like recording a show to watch later, could not be banned simply because it was also capable of being used for copyright infringement. This ruling not only saved the VCR industry but also paved the legal way for virtually all modern consumer-level recording technologies, from DVRs to streaming platforms.

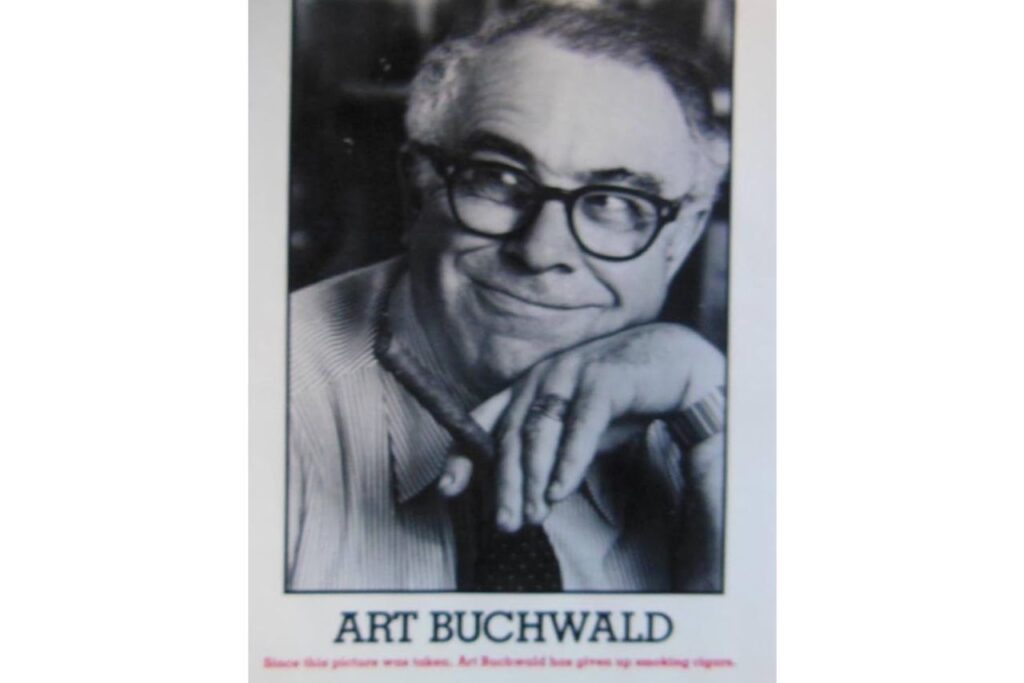

3. Buchwald v. Paramount Pictures

Writer Art Buchwald successfully sued Paramount Pictures in 1990, claiming the studio had breached an implied contract by using his story concept as the basis for the Eddie Murphy-starring film Coming to America. Buchwald had pitched a treatment, King for a Day, which Paramount initially optioned but later abandoned. When Coming to America became a box office hit, Buchwald claimed the plot was substantially derived from his work. The court agreed, ruling in Buchwald’s favor and setting a significant precedent regarding Hollywood’s use of ideas and pitches. Although the parties settled for an undisclosed amount, the case exposed the questionable “Hollywood accounting” practices used by studios to claim blockbusters were unprofitable, thereby avoiding paying contracted profit participants.

4. Midler v. Ford Motor Co.

In this 1988 case, singer and actress Bette Midler successfully sued the Ford Motor Company and its advertising agency for using a sound-alike singer in a TV commercial after Midler herself had refused to participate. The ad agency hired a studio singer who could mimic Midler’s distinctive voice and style in a rendition of her hit song “Do You Want to Dance.” The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Midler, creating a new legal right that prevents the unauthorized use of a celebrity’s unique vocal performance for commercial gain. This decision expanded publicity rights beyond just a person’s name, image, and likeness to include the specific, recognizable quality of their voice, thus protecting a key aspect of a performer’s artistic identity. While not 100% a Hollywood story, we felt this one was worth including.

5. Anderson v. United Artists

The 1950s saw a major shift in how Hollywood compensated creatives, and this 1963 lawsuit by writer Robert Anderson against United Artists over the film The Nun’s Story highlighted a common practice known as “net profits.” Anderson was promised a share of the film’s net profits, but the movie was so successful that the studio claimed it was still not profitable due to high distribution fees and overhead costs, the classic Hollywood accounting maneuver. While the specific details are complex, this case helped to illuminate the deep-seated issues with net profit contracts, which often ended up paying zero to creative talent, no matter how commercially successful a film became. It fueled decades of subsequent lawsuits over transparent accounting.

6. Gracen v. Bradford Exchange

This 1980 Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals case is a pivotal decision in copyright law, particularly for derivative works like movie merchandise and collectibles. The dispute was over the copyrightability of paintings based on the movie The Wizard of Oz, intended for use on collector’s plates. The court ruled that the paintings, while based on existing copyrighted characters, lacked the necessary level of “originality” to qualify for their own separate copyright protection. This standard helped clarify the line between a genuinely new creative work and a mere reproduction, significantly impacting the licensing and control studios maintain over their intellectual property in the massive and lucrative merchandising market.

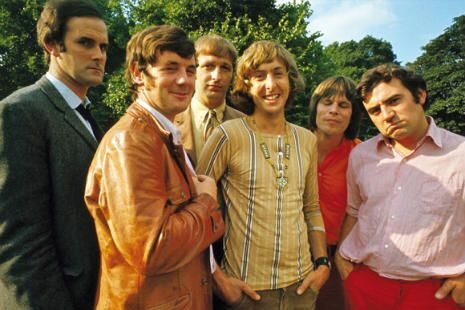

7. Monty Python v. American Broadcasting Companies

In this 1976 case, members of the British comedy troupe Monty Python successfully sued ABC for unauthorized editing of their televised sketches, which they felt distorted their work and damaged their artistic reputation. ABC had acquired the rights to broadcast two of the group’s television programs but edited out approximately 24 minutes of content, primarily to make room for commercials and remove material they deemed offensive. The Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that ABC’s extensive editing amounted to a violation of the Copyright Act and constituted “mutilation” of the work. This decision was a significant victory for creative control and established a legal basis for protecting the “integrity” of an artistic work from unauthorized alteration, even after distribution rights are granted.

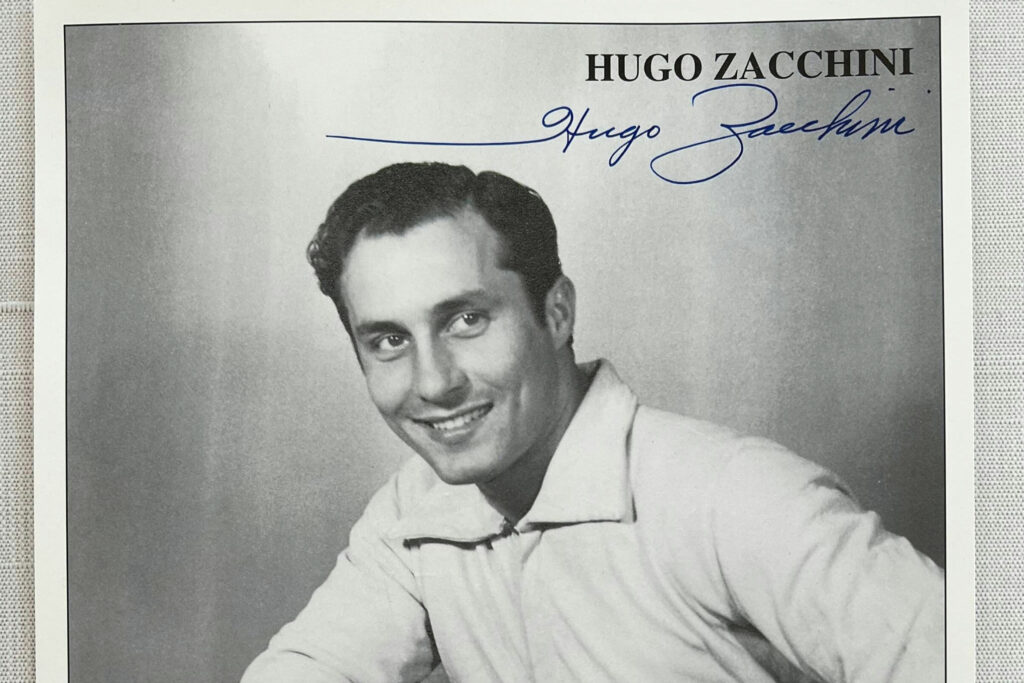

8. Zacchini v. Scripps-Howard Broadcasting Co.

This 1977 Supreme Court case involved a “human cannonball,” Hugo Zacchini, whose entire 15-second act was filmed and broadcast on a local TV news program without his consent. Zacchini sued for the unauthorized appropriation of his professional property. The Supreme Court ruled in his favor, affirming that the First Amendment (freedom of the press) does not grant the media immunity when they broadcast a performer’s entire act without permission. The decision recognized a performer’s “right of publicity,” protecting their proprietary interest in their performance to encourage the production of creative works, drawing an analogy to copyright and patent law. This strengthened the rights of performers to control and profit from their public performance.

9. Lugosi v. Universal Pictures

Following the death of famed Dracula actor Bela Lugosi, his widow and son sued Universal Pictures in 1979, claiming the right to control the commercial use of Lugosi’s likeness from the film, which Universal had been licensing for merchandise. The California Supreme Court initially ruled against the Lugosi family, stating that the right of publicity does not automatically descend to one’s heirs unless the celebrity had actively exploited that right commercially during their lifetime. While later legislation in California changed this, now recognizing a postmortem right of publicity, this ruling once stood as a crucial limitation, influencing how estates planned for and protected a celebrity’s commercial legacy in their name and image.

10. Kelly v. Arriba Soft Corp

The rise of the internet introduced new legal challenges to copyright, and this 2002 Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals case was one of the first to tackle digital image search engines. Photographer Leslie Kelly sued a search engine operator for displaying her copyrighted photos as low-resolution “thumbnail” images in search results. The court ultimately ruled that the use of thumbnails was a “fair use” under copyright law because it served a transformative purpose, indexing the images on the web, and did not harm the market for the original, high-resolution photos. This seminal ruling was crucial in validating the business model of image search engines and establishing key precedents for the digital display of copyrighted works on the internet.

11. Nichols v. Universal Pictures Corp.

In this 1930 case, playwright Anne Nichols sued Universal over similarities between her play Abie’s Irish Rose and the studio’s film The Cohens and the Kellys. While the stories shared a similar theme, a romance between members of different, warring ethnic groups, the court ruled that only the expression of an idea, not the idea itself, is copyrightable. Judge Learned Hand famously established the “abstractions test,” which states that a literary work’s plot can be described as a series of increasing abstractions, and copyright protection diminishes as the abstraction increases. This standard is still used to determine how much a subsequent work can borrow from a preceding one without infringing copyright, significantly defining the boundary between inspiration and illegal copying.

12. Mann v. Columbia Pictures

This 1986 California Court of Appeals decision arose from a dispute over the film Ghostbusters. Writers Bernard Mann and Douglas Land claimed Columbia Pictures stole their idea for a screenplay about paranormal investigators. While the court ruled against the plaintiffs, it reinforced the core principle that ideas themselves are not legally protected; only a concrete expression of an idea can be copyrighted. However, the case is notable for clarifying the legal requirements for a “submission agreement,” a contract commonly used in Hollywood that dictates the terms under which an idea is reviewed, thereby protecting studios from incessant litigation by defining the conditions under which they can consider outside material.

13. Doe v. TCI Cablevision

This 2003 Missouri Supreme Court case addressed the unauthorized use of a celebrity’s identity in a promotional context. Retired professional hockey player Tony Twist sued a comic book publisher and its distributor, TCI Cablevision, for using his name as the alter ego of a villain in the Spawn comic series. Twist, who had built a brand around his intimidating persona, argued the association harmed his ability to market himself. The court ruled in his favor, applying the “predominant use” test: if the use of the celebrity’s identity is primarily for commercial gain (as opposed to artistic expression), it violates the right of publicity. This case strengthened the protection of athlete and celebrity branding against unauthorized commercial appropriation in non-traditional media.

14. United States v. Paramount Pictures, Inc

This 1948 Supreme Court antitrust decision, often simply called the “Paramount Decrees,” was arguably the most impactful legal case in Hollywood history. The ruling forced the five major studios, Paramount, MGM, Warner Bros., 20th Century Fox, and RKO, to divest themselves of their movie theater chains. Prior to this, studios controlled the entire chain of production, distribution, and exhibition, a practice that stifled independent filmmaking through methods like “block booking,” where theaters had to purchase a bundle of films to get the hits. The divestiture shattered this vertical integration, effectively ending the classic studio system’s chokehold, opening the door for independent producers and a greater variety of films, and changing the economic structure of the industry forever.

15. Rogers v. Grimaldi

The 1989 Second Circuit Court of Appeals decision in Rogers v. Grimaldi is a cornerstone of intellectual property law regarding the use of famous names in creative titles. The case involved actress Ginger Rogers, who sued the filmmakers of the movie Ginger and Fred, claiming the title misled audiences into thinking she was involved. The court established the Rogers Test, which states that a trademark (like a celebrity’s name) can be used in the title of an artistic work unless the title has “no artistic relevance” to the work whatsoever, or if it explicitly misleads the consumer as to the source or content. This ruling provided important legal protection for artistic expression, preventing celebrities from overly restricting creative works that simply reference them.

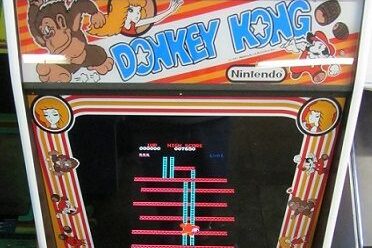

16. Universal City Studios, Inc. v. Nintendo Co., Ltd.

This 1984 lawsuit was a significant legal battle in the nascent video game industry. Universal City Studios sued Nintendo, claiming that the company’s arcade game Donkey Kong infringed on the copyright of its film property, King Kong, alleging that the big ape kidnapping a beautiful woman was a direct copy. The court ruled decisively in favor of Nintendo, finding that the idea of a giant ape was in the public domain and that the differences between the characters and story were sufficient to avoid copyright infringement. Crucially, the court also found that Universal had knowingly made meritless claims, forcing them to pay Nintendo’s legal fees, which was a huge validation for the creative autonomy of the video game medium.

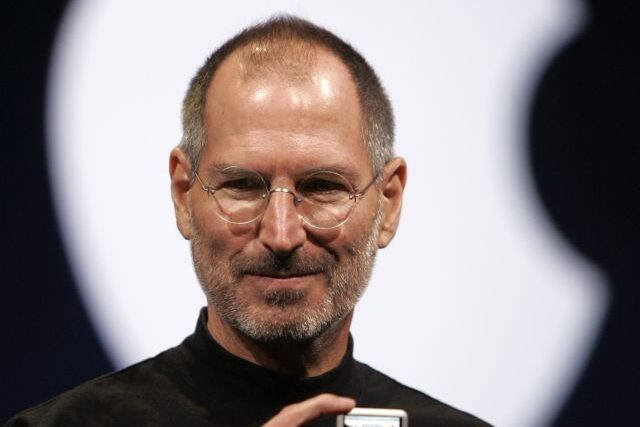

17. Apple Corps v. Apple Computer

While primarily about music and technology, the decades-long legal battle between The Beatles’ company, Apple Corps, and Steve Jobs’ Apple Computer Inc. (now just Apple) had profound implications for how media conglomerates define and defend their core business. The dispute centered on trademark infringement, with Apple Corps claiming that Apple Computer’s ventures into the music business violated an earlier agreement to stay out of the music field. The successive settlements and agreements defined incredibly complex lines of business segmentation, highlighting the increasingly blurred boundaries between technology, media, and content. The final settlement in 2007 led to Apple Computer legally owning all the Apple trademarks and licensing them back to Apple Corps, paving the way for The Beatles’ music to eventually appear on iTunes.

18. United States v. ASCAP

The American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) and Broadcast Music, Inc. (BMI) are the two major performance rights organizations in the US, responsible for collecting royalties for musical works. For decades, the US government has overseen a consent decree against ASCAP (and a similar one against BMI) to prevent them from becoming monopolies and unfairly restricting the use of music. This long-running antitrust action, which began in 1941 and has been revised many times, dictates how performance licenses are issued and priced. Without this continuous legal oversight, the licensing landscape for everything from radio and television broadcasts to film synchronization rights would be vastly more restrictive and expensive, thus shaping the fundamental economics of music and video content creation.

The legal trenches of Hollywood have always been as dramatic as its movie sets, and these 18 cases, spanning antitrust, intellectual property, and performer rights, may not have the same star power as the blockbusters they influenced, but their verdicts and precedents are the invisible scaffolding holding the modern entertainment industry together. They are the quiet, critical foundation of creative freedom, corporate control, and consumer rights in the world of media.

This story 18 Forgotten Court Cases That Shaped Hollywood’s Future was first published on Daily FETCH