1. Standing When An Adult Entered

School in the 1950s and 60s had an unspoken rhythm that children followed without question, and it always showed itself when an adult entered the classroom. Chairs slid back instantly as students stood in silence, often before they even looked up. No one explained why it mattered. It was simply expected. Former students often say it felt automatic, like muscle memory. Standing showed respect, obedience, and awareness all at once. Lessons paused, pencils stopped moving, and the room shifted the moment authority crossed the doorway. At the time, it felt normal, not strict, because everyone did it every day.

Looking back now, the rule feels formal in a way modern classrooms no longer recognize. Respect today is shown through listening and engagement, not physical movement. Back then, the body responded before the mind had time to think. Standing reminded students who held power in the room. It quietly shaped how children understood authority and their place within it. What once felt ordinary now feels like a clear symbol of how school life placed obedience ahead of comfort or conversation.

2. Silent Lunchtimes

Lunch was not treated as a break filled with noise and laughter. In many schools, students were expected to eat quietly, often under close supervision. Talking was discouraged or not allowed at all. One former student remembered hearing utensils more clearly than voices. Teachers believed silence encouraged good manners and prevented trouble. Lunch became another controlled part of the day rather than a pause from structure. Children accepted it because it was all they knew. Quiet meant doing the right thing, even when surrounded by friends.

Today, lunchtime is seen as a social reset. Looking back, the silence feels lonely. Students missed small moments of connection that now seem important. The rule reinforced the idea that school controlled every part of the day, even moments meant for rest. At the time, no one questioned it. Only later did people realize how strange it was to sit together every day without being allowed to simply talk.

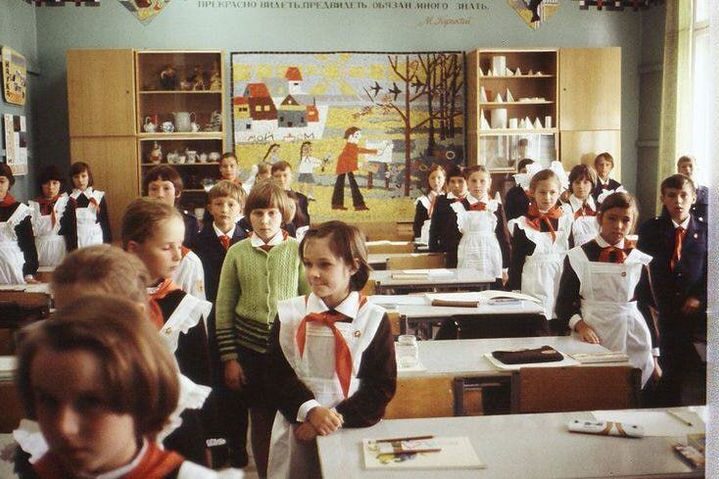

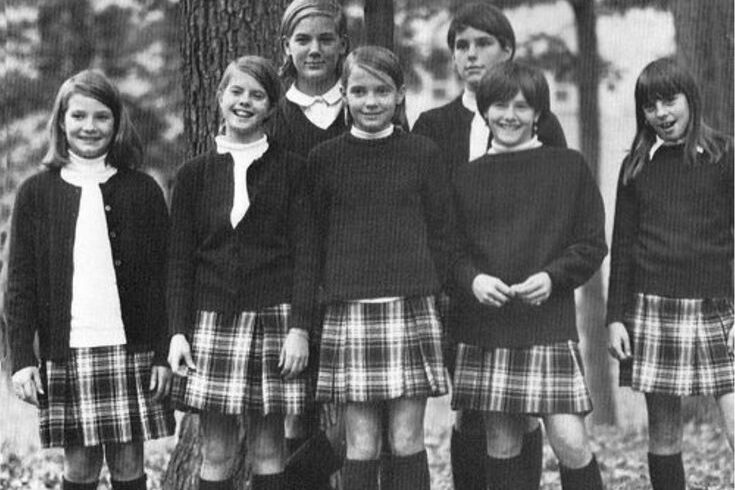

3. Dresses Were Mandatory For Girls

Girls were required to wear dresses or skirts to school every day, regardless of weather or activity. Pants were considered inappropriate. Many women still remember holding their skirts down or sitting carefully on classroom chairs. Comfort was not a consideration. The rule focused on appearance and behavior rather than learning. Teachers believed proper dress reflected good upbringing. Girls accepted it because everyone else did. It became another quiet expectation folded into daily school life.

Today, clothing is meant to support learning and movement. Looking back, the rule feels limiting. Girls spent energy managing their clothes instead of focusing fully on lessons. The classroom reinforced narrow ideas about how girls should look and behave. What once felt normal now reads as an unnecessary restriction. It reminds us how school rules often mirrored social expectations, shaping behavior long before anyone stopped to ask if those expectations truly made sense.

4. Boys Had To Keep Their Hair Short

For boys in the 1950s and 60s, hair length was not a personal choice. Schools closely monitored how boys looked, and hair that touched the ears or collar could lead to warnings or being sent home. Teachers believed neat hair showed discipline and respect. One former student recalled feeling nervous when haircuts were overdue, knowing it might become a school issue. The rule was rarely questioned. Short hair became part of what it meant to be a good student. Boys learned early that appearance mattered just as much as behavior.

Today, hair is seen as expression rather than a sign of character. Looking back, the rule feels intrusive. Something harmless became a way to enforce conformity. Boys were taught that blending in was safer than standing out. Hair became a quiet lesson in obedience. What once felt ordinary now feels unnecessary, reminding us how schools once shaped identity by controlling even the smallest personal details.

5. Left-Handed Writing Was Corrected

Left handed students were often told to switch hands when writing. Teachers believed writing with the right hand was proper and neater. Some students had their left hand held or guided away from the page. One woman later remembered feeling confused about why something natural was suddenly wrong. At the time, teachers thought they were helping children succeed. Students adjusted because they were expected to. The rule became another silent correction folded into daily lessons.

Today, handedness is understood as natural. Looking back, the practice feels misguided. Forcing children to change caused frustration and discomfort. A simple difference was treated as a flaw. School was not built to adapt to students. Students adapted to school instead. This rule quietly taught children that being different meant needing correction, a lesson many carried with them long after leaving the classroom.

6. No Talking In The Hallways

Hallways in many schools were meant for movement, not conversation. Students walked in straight lines, often with hands at their sides, keeping their voices low or silent. Teachers believed quiet hallways prevented chaos and showed discipline. One former principal explained that noise meant loss of control. For students, it became another habit learned without explanation. Between classes, children focused on getting from one room to another without drawing attention. Laughter and chatter were saved for outside school hours. At the time, the rule felt ordinary. Hallways were not places to linger or connect. They were spaces to pass through quickly and quietly.

From a modern perspective, the silence feels excessive. Today, hallways are often filled with conversation, energy, and quick moments of connection. Back then, those small opportunities were tightly managed. Looking back, many people realize how much control schools held over even the briefest moments of the day. The rule made school feel formal and rigid, more like an institution than a community. It taught children that even in transition, behavior was monitored. Silence became another form of obedience practiced daily without question.

7. Cursive Writing Was Required

Cursive writing was not optional in many classrooms. Students spent hours practicing loops, slants, and spacing until their handwriting met expectations. Printing was considered immature or careless. Teachers believed neat cursive showed discipline and attention to detail. One teacher often told students their handwriting reflected their character. Children worked carefully, erasing mistakes and rewriting lines until they were perfect. At the time, cursive was necessary for letters, exams, and formal communication. Students accepted the pressure because everyone faced it. It was simply part of learning how to be taken seriously.

Today, cursive has largely faded from classrooms. Technology has changed how people communicate. Looking back, the emphasis on perfect handwriting feels intense. Still, many adults remember those lessons clearly. The quiet concentration, the lined paper, and the effort to make each letter match the example. Cursive was less about communication and more about precision. It taught patience and repetition, even if the skill itself is rarely used now. What once felt essential now feels like a reminder of how education follows the tools and values of its time.

8. Discipline Happened In Front Of Everyone

When a student broke a rule, correction often happened publicly. Teachers believed discipline worked best when others witnessed it. One former student recalled feeling frozen as attention turned toward them. The idea was that embarrassment would prevent repeat behavior. At the time, this approach was accepted. Adults saw it as firm but fair. Children learned quickly what not to do by watching others. Discipline was not private or gentle. It was meant to be visible. Students grew used to the idea that mistakes came with an audience.

Today, that approach feels harsh. Schools now recognize the importance of dignity and emotional safety. Public discipline often caused shame rather than understanding. Looking back, many adults remember those moments more clearly than the lessons that followed. The fear of being singled out stayed with them. This rule reflects a time when authority relied on exposure rather than conversation. It shows how education once valued control over care, even when it left lasting impressions that had little to do with learning.

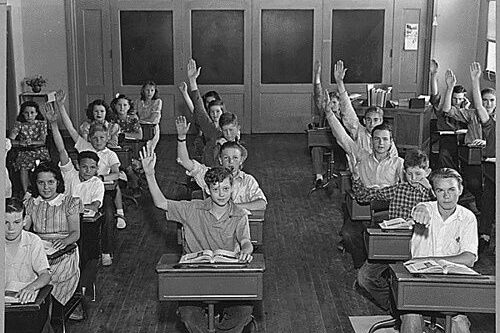

9. Teachers Were Not To Be Questioned

In many classrooms during the 1950s and 60s, a teacher’s word was final. Students were expected to listen, accept, and move on. Asking questions that challenged an explanation could be seen as disrespectful. One former student later said they learned early that curiosity had limits. Teachers stood as authority figures whose role was to instruct, not debate. Lessons moved forward without pause, and students followed along quietly. The idea was that order created learning. Children who questioned too much risked being labeled difficult. At the time, this structure felt normal. Respect meant silence, and understanding was assumed rather than discussed.

Today, classrooms encourage discussion, curiosity, and critical thinking. Looking back, the rule feels restrictive. Many adults now realize how many questions they kept to themselves. Learning became about memorizing what was given, not exploring ideas further. The absence of dialogue shaped how students viewed authority well into adulthood. Teachers were not wrong for expecting respect, but the lack of space for conversation limited growth. This rule reflects a time when education valued obedience over exploration, even though real understanding often begins with a simple question spoken out loud.

10. Home Economics Was Assigned To Girls

Girls were often placed into home economics classes without being asked. Cooking, sewing, and household management were considered essential skills for their future. Counselors and teachers believed they were preparing girls for adult life. One woman later recalled being handed a sewing kit while wondering why she could not take science instead. At the time, this separation felt ordinary. No one explained it as a limitation. It was framed as preparation. Girls followed the path laid out for them, assuming it was simply how school worked.

Looking back now, the rule feels quietly confining. Education today aims to expand options, not narrow them. Many women later realized how early expectations shaped confidence and career choices. Being placed in certain classes sent messages about what was possible and what was not. While practical skills are valuable, choice matters just as much. This rule reminds us how schools once reflected society’s assumptions rather than challenging them. What felt like guidance then now reads as an early boundary drawn around potential.

11. Shop Class Was Reserved For Boys

While girls learned domestic skills, boys were directed toward shop class. Woodworking, metalwork, and mechanical lessons were seen as practical and appropriate for them. One former student remembered being enrolled without discussion. The belief was that boys needed hands on skills for future work. At the time, it felt natural. Boys accepted the assignment because everyone else did. Interest did not factor into the decision. The class you took said something about who you were expected to become.

Today, that kind of separation feels outdated. Students are encouraged to explore interests freely, regardless of gender. Looking back, many men realize how little choice they had in shaping their education. Some enjoyed shop class. Others felt out of place. The rule shaped identity early, reinforcing ideas about work and worth. It reflects a time when schools prepared students for specific roles instead of helping them discover their own paths. Education has since learned that curiosity thrives when choice is allowed.

12. Makeup And Jewelry Were Not Allowed

Any sign of makeup or jewelry could result in discipline. Schools enforced a plain appearance, believing it kept students focused. Teachers often said school was not a place for showing off. For girls especially, appearance was closely monitored. A necklace or a hint of lipstick could lead to correction. At the time, it felt like part of being a student. Personal expression was something saved for outside school walls.

Today, small expressions of style are widely accepted. Looking back, the rule feels controlling rather than protective. Appearance has little to do with learning, yet it was treated as a distraction that needed removal. Many adults now recognize how closely schools once managed identity. Students were expected to blend in, not stand out. This rule taught children early that fitting a standard mattered more than expressing themselves, even in harmless ways.

13. Perfect Attendance Was Treated As A Virtue

Perfect attendance was praised and rewarded. Missing school was discouraged, even when a child felt unwell. Parents often sent children to school unless illness was severe. Awards were given to those who never missed a day. At the time, attendance was seen as a sign of responsibility. Being present mattered above all else. Children learned that showing up was expected, regardless of how they felt.

Today, health is prioritized more carefully. Looking back, the pressure feels misplaced. Encouraging sick children to attend now seems risky. Many adults remember going to school when rest would have been better. The rule valued endurance over wellbeing. It reflects a time when commitment was measured by presence alone. Education has since learned that learning happens best when students are healthy, not simply seated at a desk.

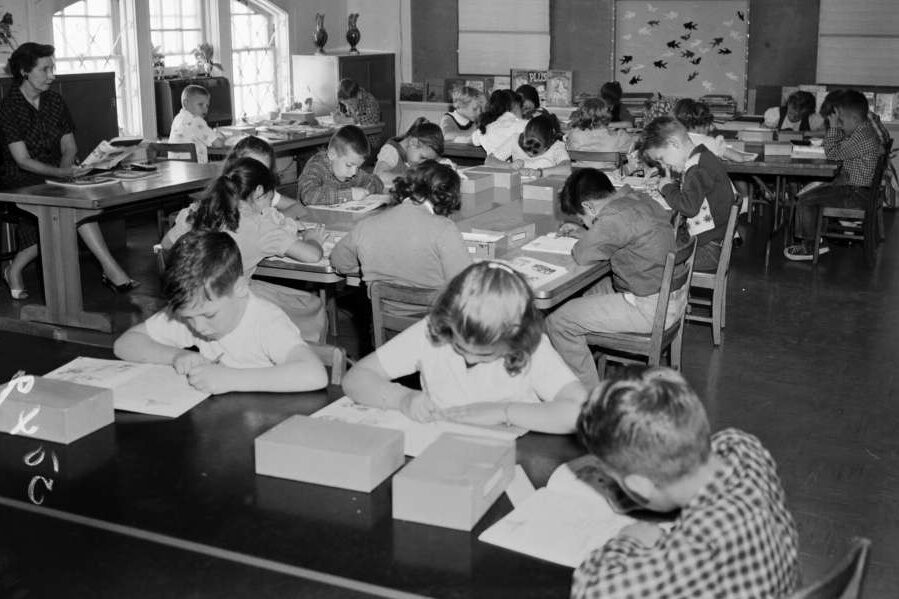

14. Memorization Over Understanding

Classrooms in the 1950s and 60s placed heavy emphasis on memorization. Students were expected to repeat facts, dates, and definitions exactly as taught. Success meant remembering the correct answer, not necessarily understanding why it mattered. One former student recalled studying by repetition alone, trusting that recall was the goal. Lessons moved quickly, and there was little time to pause and explore ideas deeply. Teachers believed strong memory skills built intelligence and discipline. At the time, this approach felt normal. Students followed along, reciting information until it stuck, believing that was what learning looked like.

Today, education focuses more on reasoning and application. Looking back, many adults realize how limited that approach felt. Some students who understood concepts struggled with recall and were labeled weak learners. Others memorized well but lacked deeper comprehension. The rule shaped confidence in subtle ways, rewarding one kind of mind over others. It reminds us that education evolves as understanding grows. What once felt effective now feels incomplete, showing how learning is about more than simply remembering what was said.

15. Physical Punishment Was Accepted Discipline

Physical punishment was allowed in many schools and was viewed as a normal part of discipline. Rulers, paddles, or sharp taps were used to correct behavior. Teachers believed it reinforced order and respect. One former student remembered the fear more clearly than the lesson itself. At the time, parents often supported the practice, trusting schools to enforce discipline. Children accepted it as part of school life. Complaints were rare because the rule was widely accepted.

Today, this practice feels deeply unsettling. Education now prioritizes safety and emotional wellbeing. Looking back, many adults realize how fear replaced understanding. Physical punishment taught compliance, not growth. The memory of those moments often lasted longer than any academic lesson. This rule reflects a time when authority relied on control rather than trust. It stands as one of the clearest examples of how values in education have shifted toward care and respect.

16. Uniforms Had No Room For Flexibility

School uniforms were enforced with strict precision. Shirts were tucked, shoes were specific, and deviations were corrected immediately. One former student recalled feeling invisible in a room full of identical outfits. Uniforms were meant to promote equality and focus. At the time, they were accepted as part of school identity. Personal style was not considered important within school walls. Students learned to blend in and follow the standard set for them.

Today, even uniform schools often allow small expressions of individuality. Looking back, the rigidity feels excessive. Clothing became another way schools enforced conformity. While uniforms can create unity, the lack of flexibility removed personal expression entirely. This rule taught students early that standing out was discouraged. It reflects a time when sameness was valued over individuality, shaping how students saw themselves within a system larger than them.

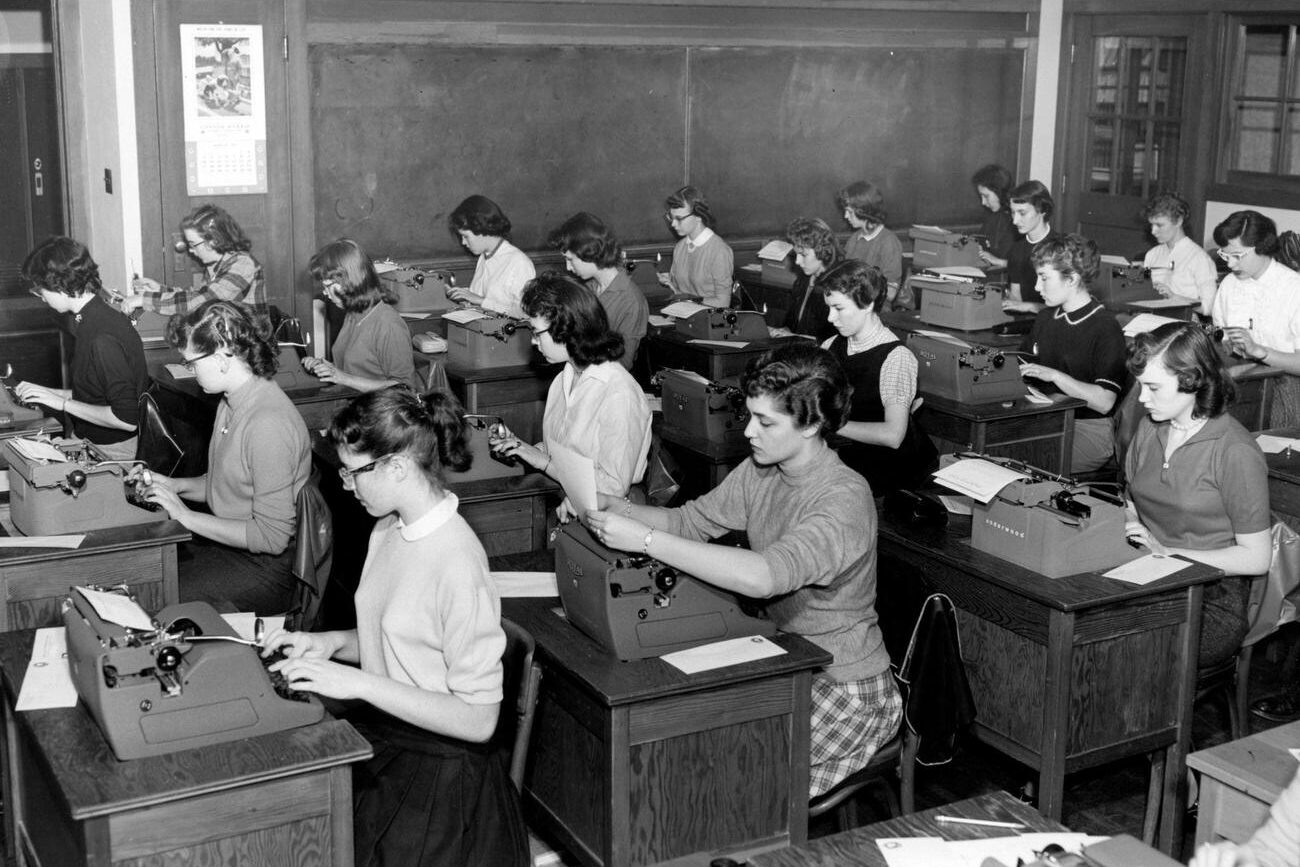

17. Typing Was Considered A Girl Skill

Typing classes were often offered only to girls and focused on office preparation. Teachers believed these skills would help girls find work later in life. Boys were rarely included. One woman recalled learning typing while boys were sent elsewhere. At the time, it was framed as opportunity, not limitation. Girls followed the curriculum without questioning why it was divided this way.

Today, typing is a basic skill for everyone. Looking back, the separation feels narrow. Education mirrored workplace expectations rather than expanding them. Many students later realized how early these divisions shaped confidence and career paths. This rule shows how schools once prepared students for predefined roles instead of open possibilities. It is a reminder that access to skills should never depend on assumptions about future paths.