1. Dallol: Toxic, Super‑Hot Ghost Landscape

Dallol sits in Ethiopia’s Danakil Depression, once inhabited for salt and sulfur mining, but now a near-ghost town. Its environment averages 35 °C, features acid springs with pH below 1, mineral terraces and toxic hydrothermal gases. The area is too harsh for most life, including humans; very few, if any, residents remain. This area holds the world record for the highest average temperature in any inhabited location, but modern inhabitants are typically transient salt collectors or scientists. Acidic vents, bubbling springs, and metal-rich fumes make permanent habitation nearly impossible. Dallol now stands as a vivid warning: Earth’s extreme beauty may be unlivable.

2. Chernobyl: Exclusion Zone Home

Behind the irradiated remains of the 1986 nuclear meltdown lies a small, aging population who returned, often illegally, to the Exclusion Zone. About 197 residents, mostly over 60 years old, are now informally permitted to stay in abandoned villages and live simple lives despite lingering radiation. They accept the risks and refer to their homes as rooted in heritage and attachment. Many resettlers, such as Buntova and Lapiha, have lived there for decades. They maintain modest brick houses, care for rescued dogs and honey bees, and enjoy a quiet life, even though children are forbidden inside due to radiation vulnerability. These seniors choose stability over safety, saying they’re happy in Chernobyl despite its hazards.

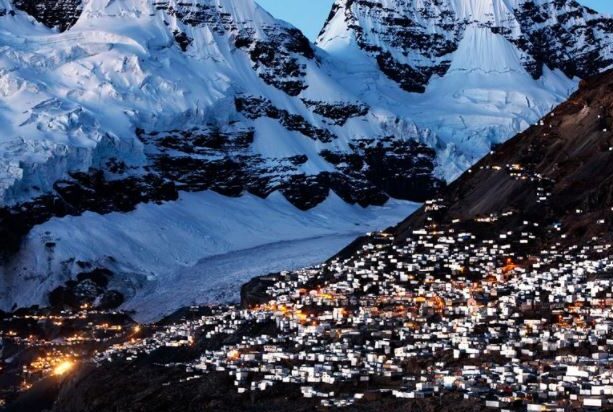

3. La Rinconada: High‑Altitude Gold Hell

At over 5,100 m above sea level, La Rinconada in Peru is the world’s highest permanent settlement, housing around 30,000 people. Residents breathe half as much oxygen as at sea level, suffer altitude sickness, and endure freezing nights amid gold mine pollution, mercury exposure, no plumbing, and widespread poverty and crime. Miners work under the informal “cachorreo” system, no salary for most of the month, but keep whatever gold they extract at the end. Medical services are virtually nonexistent. Respiratory illnesses, mercury poisoning, violent crime, and unregulated mining are common, but many remain driven by the chance to strike it rich despite the cost.

4. Mount Merapi: Living on a Volcano’s Slopes

Mount Merapi in Indonesia is among the world’s most active volcanoes, over 1 million people live within a 10 km radius. Its fertile slopes support farms and fruit plantations, but eruptions are frequent. In 2010, it killed over 347 people, displaced around 15,000, yet many villagers refused to relocate due to deep cultural attachment and economic necessity. Villagers treat the volcano as more than a hazard, they see it as their ancestral land. Local beliefs view Merapi as a spiritual being and attribute eruptions to moments of anger or balance. Inhabitants have turned eruption sites into tourism attractions and organized evacuation drills, but still choose home over evacuation zones because of farming, livestock care, and heritage ties.

5. Lake Nyos Region: Risk of “Invisible” Death

In Cameroon, Lake Nyos exploded in 1986, releasing a massive cloud of CO₂ that suffocated 1,700 villagers and 3,500 livestock in nearby towns and villages overnight. Though mitigation efforts have reduced risk, thousands still live on Nyos’s slopes in areas where deadly gas can remain trapped underground and suddenly release again. Since then, engineers have been artificially removing the gas from the lake through piping. The gas burst in 1986 from the 200-meter deep Lake Nyos was so violent that water washed over the 80-meter high promontory in the foreground. Despite the danger, families stay for farmland and because relocation resources are limited. Cultural beliefs once guided safer settlement choices, but modern migration has moved more people into the hazard zone.

6. Centralia: Town on Fire Underground

Centralia, Pennsylvania, has been fighting an underground coal fire since 1962. Initially set in a town dump, the fire spread into abandoned mines and now threatens roadways and foundations with carbon monoxide, heat vents, and sinkholes. Despite relocation efforts that bought out nearly the entire town, fewer than a dozen residents chose to stay, owning homes they no longer control under eminent domain laws, simply because that’s home to them. These last residents face daily dangers and legal battles. Houses fill with toxic gases, sidewalks buckle, and the landscape regularly shifts as the earth burns below. Local lore mentions harvesting tomatoes through warm ground in winter, but the overall impact is deadly: government agencies deemed the area unsafe and most people accepted relocation buyouts. Still, these stubborn few live amid smoke and ash as the fire smolders on, expected to burn for centuries.

7. Norilsk: Arctic’s Toxic Industrial City

Norilsk, Russia, lies above the Arctic Circle and is home to around 170,000 people. It is one of the world’s coldest cities (winters dip below −50 °C) and one of the most polluted, where sulfur dioxide emissions from Norilsk Nickel smelting have choked the surrounding tundra and poisoned the air and soil. Life here is a struggle between profit and survival. Residents receive high wages, but many suffer from respiratory illnesses and are exposed to heavy metal pollutants every day. The city is physically isolated, accessible only by air or river, and even buildings can shift as permafrost thaws, leading to infrastructure damage and increasing breakout of toxins into the environment.

8. Mogadishu: Resilience Amid Conflict

Mogadishu, Somalia’s capital, remains home to over two million people despite decades of civil unrest, terrorism, and political instability. Daily life involves navigating threats from al‑Shabaab militants, bombings, and shifting control zones, even as some permit the installation of CCTV cameras to improve safety. For many residents, the choice is between displacement or staying in a city scarred by conflict but full of community ties. Local entrepreneurs and students speak of the cameras bringing both reassurance and retaliation risks; some business owners have been targeted simply for installing surveillance. Life in Mogadishu is shaped by courage, persistence, and a refusal to abandon roots despite persistent threats.

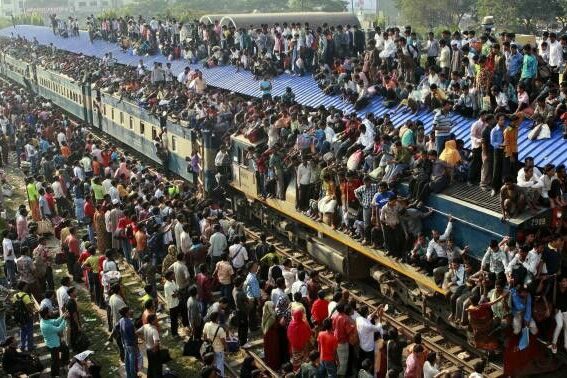

9. Dhaka Slums: Overcrowded, Unsanitary, Unrelenting

More than 4 million people live in Dhaka’s informal slums, dense, tiny settlements lacking clean water, sanitation, ventilation, or privacy. Entire families share cramped tin‑sheet rooms barely 100 sq ft, often in areas where trash and sewage flow openly. Waste dumping increases mosquito breeding, respiratory and waterborne illnesses flourish and malnutrition is widespread, making slum life hazardous every day. Children, in particular, suffer from diarrhoea, typhoid, and stunted growth. Most slum dwellers lack formal medical care, turning instead to informal pharmacies or avoiding healthcare entirely. The social and mental toll is equally heavy: loneliness, domestic violence, and diminished prospects for education and professional life persist amid unsafe infrastructure, flooded lanes, and collapsing homes during rainy seasons.

10. Amazon Region: Wild, Remote, and Risky

Millions live across the Amazon basin, Indigenous communities, rubber tappers, riverside villages, facing dangers from venomous tribes, disease-bearing mosquitoes, daily flooding, and extreme isolation. Medical access is limited, and transportation often means long boat rides or treks through dense rainforest. Urbanization or environmental destruction can displace communities into even harsher zones. These communities endure both natural risks like malaria, dengue, and unknown pathogens and social threats including land conflicts and illegal mining. Yet residents remain deeply tied to ancestral territories, cultures, and livelihoods rooted in forest ecology. Despite the danger, they have adapted survival skills, traditional knowledge, and resilience that sustain them in one of Earth’s most challenging environments (Note: specific citations for Amazon sources weren’t found in this search but are well‑documented in global human geography literature).

11. Bangladesh Coastal Zone: Living With Cyclones and Salt Water

Over 40 million people live along Bangladesh’s 580 km-long coastal zone, facing repeated cyclones, storm surges, coastal erosion, and saltwater intrusion. Cyclone Sidr in 2007 alone killed between 3,400 and 15,000 people, making this region one of the most disaster‑prone on earth. Despite huge risks, strong economic and cultural ties to land keep residents rooted here. Efforts like the World Bank–backed embankment upgrades, cyclone shelters, mangrove plantations, and early‑warning systems now protect hundreds of thousands of people. Still, ongoing climate change is intensifying storms and salinity in drinking water, leading to health issues including chronic kidney disease and pre‑eclampsia among pregnant women.

12. Erta Ale, Ethiopia: Inhabitants by a Lava Lake

Erta Ale is a continuously active volcano in Ethiopia’s Danakil Depression, hosting a persistent lava lake. The surrounding Afar communities live within a few kilometers of molten rock, sulfur gases, and shifting tectonic activity. Ethnic conflict and rare attacks on tourists highlight how political instability adds to natural danger here. Despite extreme heat, toxic fumes, remote terrain, and occasional violence, Afar pastoralists and salt traders remain. Tourism requires armed escorts and local guides, the risks are high, yet residents have adapted to life in one of Earth’s most hostile volcanic landscapes.

13. Bujumbura, Burundi: Lakeside With Instability

Bujumbura sits on Lake Tanganyika’s shores and remains home to hundreds of thousands despite persistent political unrest, ethnic tensions, poverty, and violence. While severe albino attacks have raised security concerns, residents also face limited infrastructure, youth unemployment, and recurrent protests or clashes. Everyday life in Bujumbura is shaped by resilience: markets buzz despite low formal services, children walk to school amid fragile safety conditions, and neighbors rely on informal systems when official institutions falter, weaving community endurance into daily survival.

14. Bam, Iran: Earthquake Zone Still Rebuilt

Bam was devastated in the December 2003 quake that killed around 26,000, injured 30,000, and destroyed nearly 90 percent of structures, including its historic citadel. Despite this, survivors returned to rebuild, with some families choosing to stay in rebuilt homes or remaining traditional areas near active fault lines. Construction now follows stricter seismic codes, and smaller communities have slowly re‑formed. Though much has been restored, including parts of Bam Citadel, the region remains highly vulnerable to tremors. Residents balance familiarity and heritage with ongoing earthquake risk.

15. Fukushima, Japan: Some Return to Exclusion Zone

Following the 2011 triple reactor meltdown, approximately 80,000 people were evacuated from around Fukushima Daiichi. Over a decade later, parts of zones like Katsurao village and Tamura have reopened, allowing limited return. Yet only 23 percent of eligible former residents have come back, many cite concerns over lingering radiation and lack of infrastructure. Returnees are mostly older residents who feel strong attachment to their homes and traditions. They cope with low population density, rebuilt services, and constant radiation monitoring. Even with decontamination and incentives, most families choose to stay away, illustrating how trauma and safety outweigh nostalgia.

16. Kabwe, Zambia: Town Living with Toxic Lead Danger

Kabwe, once a major colonial-era lead and zinc mining center, now houses nearly 300,000 people in a zone described by the UN as a “sacrifice zone” of industrial contamination. Mining ceased in 1994, but tailings, waste heaps of lead dust, remain uncovered and blow across adjacent residential neighborhoods, schools, and playgrounds. As many as 95% of children tested show elevated blood lead levels; nearly half require urgent medical intervention. These children suffer from slowed growth, memory problems, and learning difficulties directly linked to lead exposure. Recent reports show that rescue efforts have been fragmented: a 2020 World Bank initiative tested over 10,000 children, remediated select schools and homes, and provided treatment and educational campaigns, yet none addressed the core issue: the toxic waste piles themselves. Meanwhile, small-scale miners continue to process lead and zinc in the old mine area, spreading dust further and deepening health risks for residents.

This story 16 of the Most Dangerous Places on Earth Where People Still Live was first published on Daily FETCH