Plastic Flamingos Outnumber Species

It is a curious truth that the world often prioritises the aesthetic of nature over the preservation of the living thing itself because there are currently more plastic flamingos decorating lawns than there are real ones wading in the wild. This strange phenomenon serves as a poignant reminder of how our human obsession with kitsch decor has outpaced the biological reality of these elegant birds. Since the iconic pink lawn ornament was first designed by Don Featherstone in 1957, millions have been produced and sold globally while the actual wild populations of the six flamingo species face ongoing challenges from habitat loss. While it is lovely to see a splash of pink in a suburban garden, the disparity highlights a modern disconnect where the symbol of the animal becomes more ubiquitous than the creature it represents in the natural world.

Conservationists estimate that the global population of all flamingo species combined sits at roughly several million individuals, yet the number of manufactured plastic versions is believed to be significantly higher due to decades of mass production. These artificial birds do not require specific alkaline lakes or brine shrimp to survive, and they certainly do not have to worry about the effects of climate change on their breeding grounds. It is quite fascinating to consider that a design meant to bring a tropical feel to post-war American housing ended up becoming a demographic leader over its biological inspiration. We should perhaps look at these plastic figures not just as quirky ornaments but as a nudge to ensure that the vibrant, living birds remain a thriving part of our planet’s biodiversity rather than just a memory captured in polyethylene.

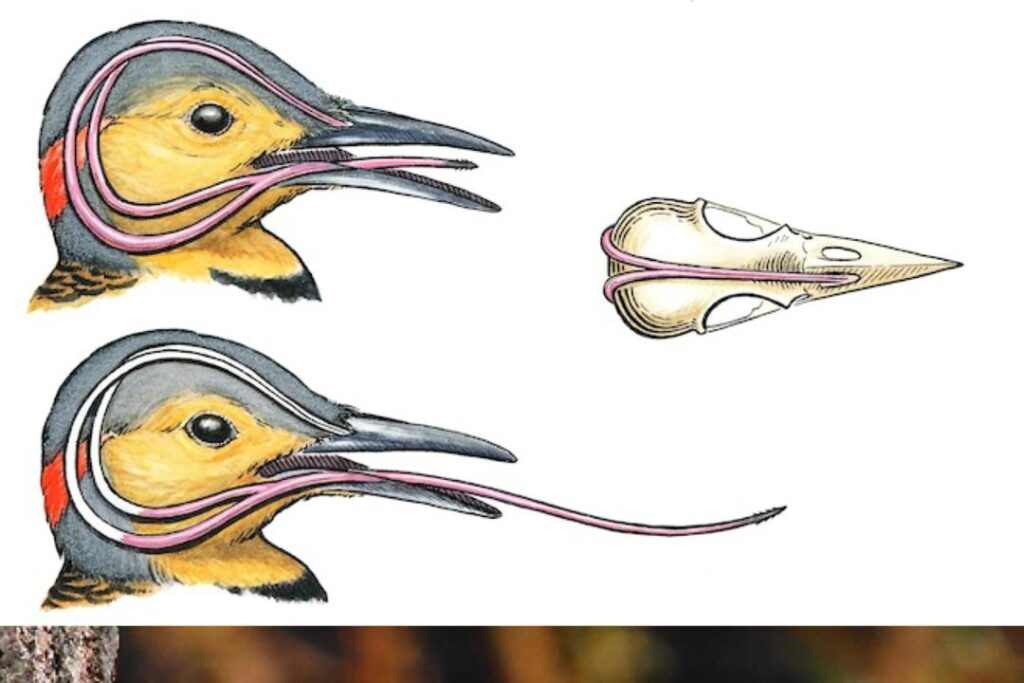

Woodpeckers Wrap Their Tongues

The sheer force of a woodpecker drumming against a tree is enough to cause severe brain damage to almost any other living creature, but these birds have a truly bizarre anatomical safeguard. A woodpecker’s tongue is so long that it cannot simply sit in its mouth; instead, it extends out the back of the jaw, wraps around the entire skull, and anchors near the nostrils. This unique structure, known as the hyoid apparatus, acts like a sophisticated safety belt or a shock absorber for the brain. When the bird strikes the wood at speeds of up to fifteen miles per hour, the tongue and its supporting bones help to distribute the impact forces away from the delicate brain tissue. It is an extraordinary example of how evolution can repurpose an organ to serve a dual function.

Beyond acting as a protective helmet, the tongue is also a highly efficient hunting tool coated in a sticky saliva that helps the bird extract grubs from deep within the bark. Some species even have tiny barbs on the tip to spear their prey once they have located it. The mechanical precision required to hammer thousands of times a day without suffering a concussion is a feat of engineering that continues to inspire the design of better protective headgear for human athletes. It is fascinating to think that the secret to surviving such intense physical trauma was literally wrapped around the bird’s head all along. Nature has a way of finding the most unconventional paths to survival, and the woodpecker’s tongue is certainly one of the most creative solutions in the avian world.

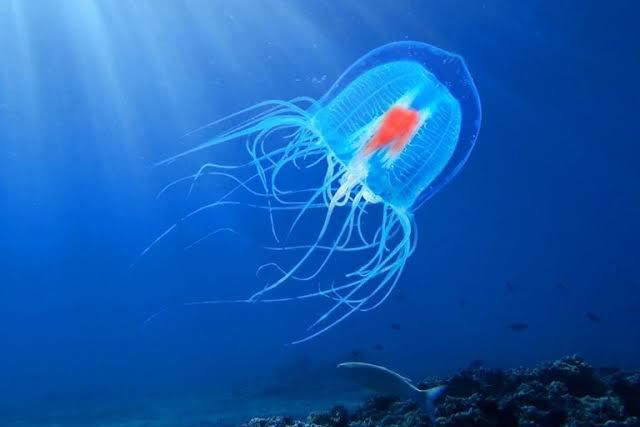

Turritopsis Is Effectively Immortal

The quest for eternal life is a staple of human folklore but a tiny creature known as the Turritopsis dohrnii has actually managed to achieve a form of biological immortality. This remarkable jellyfish, which was first discovered by scientists in the Mediterranean Sea during the late nineteenth century, has the incredible ability to hit a “reset button” when it faces physical stress or old age. Instead of dying like almost every other organism on Earth, it undergoes a process called transdifferentiation where its adult cells transform back into their earliest polyp state. It is essentially the underwater equivalent of a butterfly turning back into a caterpillar so it can start its entire life cycle all over again from scratch. This means that, barring any hungry predators or sudden environmental disasters, these tiny jellies could theoretically live forever.

While this sounds like something plucked straight from a science fiction novel, it is a very real biological mechanism that has fascinated geneticists for decades. The jellyfish begins its life as a tiny larva and eventually grows into a bell-shaped medusa, but if it becomes injured or starves, it simply folds in on itself and reverts to a blob-like cyst on the sea floor. From this cyst, a new polyp colony grows and the cycle begins anew with the exact same genetic code as the original. Scientists are studying these creatures intensely to see if their regenerative secrets could one day be applied to human medicine or the treatment of age-related diseases. It is a humbling thought that a creature no larger than a fingernail has mastered a trick that humanity has been chasing since the dawn of recorded history.

Male Seahorses Give Birth

In a complete reversal of the traditional roles found in the animal kingdom, it is the male seahorse that carries the burden of pregnancy and gives birth to the young. During the mating process, the female seahorse deposits her eggs into a specialised brood pouch located on the male’s abdomen. Once the eggs are safely inside, the male fertilises them and provides all the necessary nutrients and oxygen for the developing embryos. He even regulates the salinity of the fluid in the pouch to ensure the babies are perfectly acclimated to the seawater by the time they are born. This process can last anywhere from ten days to several weeks depending on the species and the water temperature, during which the male’s body undergoes significant hormonal changes similar to those seen in female mammals.

When the time finally comes for the young to arrive, the male experiences muscular contractions to expel the tiny “fry” into the open ocean. He can give birth to hundreds or even thousands of babies in a single session, although very few of them will survive to adulthood due to the high number of predators in the sea. This unique reproductive strategy allows the female to begin producing a new batch of eggs immediately, which increases the overall reproductive rate of the species. It is a beautiful example of evolutionary partnership where the responsibilities of continuing the lineage are shared in a way that maximizes their chances of success. The seahorse remains a symbol of the wonderful diversity of life, showing us that there is no single “right” way for nature to handle the miracle of birth.

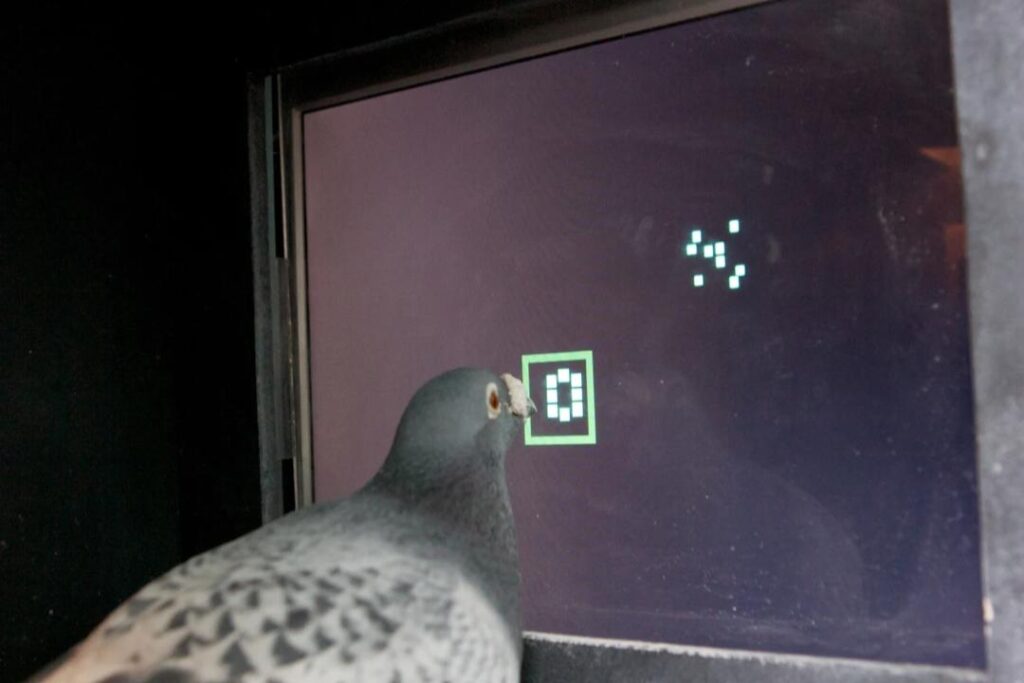

Pigeons Can Do Maths

Pigeons are often dismissed as mere “rats with wings,” but they are actually among the most intelligent birds in the world and have shown a surprising aptitude for mathematics. In a groundbreaking study published in 2011, researchers discovered that pigeons could be trained to order strings of objects based on their quantity, a skill previously thought to be exclusive to humans and primates. They were able to distinguish between groups of one, two, and three items and then apply that logic to larger numbers they had never seen before. This level of numerical competence suggests that the avian brain is capable of complex abstract reasoning despite being much smaller and structured differently than our own.

Their cognitive abilities extend far beyond simple counting because they also possess an incredible memory for faces and can even distinguish between different styles of art, such as paintings by Picasso and Monet. These birds have lived alongside humans for thousands of years and their ability to thrive in urban environments is a testament to their adaptability and problem-solving skills. By recognising patterns and making logical choices, they navigate the complexities of city life with an efficiency that we often take for granted. Understanding the hidden depth of a pigeon’s intelligence challenges our perceptions of what it means to be “smart” and reminds us that brilliance can be found in the most ordinary places. They are not just city scavengers but sophisticated thinkers with a grasp of the world that is far more mathematical than we ever imagined.

Platypus Lacks A Stomach

The platypus is famously known as a biological hodgepodge of different animals, but one of its most peculiar internal features is the fact that it completely lacks a stomach. When this Australian monotreme swallows its meal of bottom-dwelling invertebrates, the food travels directly from its gullet to its intestines without passing through a chamber for acid digestion. This evolutionary loss occurred millions of years ago, likely because the platypus’s diet did not require the heavy-duty breakdown of complex proteins that a stomach provides. It is one of the few mammals on the planet to have abandoned such a fundamental organ, joining a small club that includes certain species of fish and the echidna. This streamlining of the digestive tract is a testament to how specialized an animal can become when it finds its perfect ecological niche.

This lack of a stomach means the platypus must rely on a very different chemical process to extract nutrients from its food and it often grinds its prey using hard pads in its mouth since it also lacks teeth. Because there is no storage vat for food, the platypus must spend a significant portion of its day foraging in the water to maintain its energy levels. It is quite amazing to think that a creature which already defies so many rules of nature like laying eggs and producing venom, also functions perfectly well without a digestive staple most of us take for granted. This anatomical quirk further solidifies the platypus as one of the most intriguing puzzles in the history of biology. It proves that there are many ways to build a successful living being and that traditional organs are sometimes optional in the grand design of evolution.

Axolotls Can Regrow Brains

While many lizards can regrow a lost tail, the Mexican axolotl takes the concept of regeneration to an entirely different level by being able to regrow its limbs, heart, and even parts of its brain. This unique salamander remains in its larval state throughout its entire life, a condition known as neoteny, which seems to play a vital role in its extraordinary healing abilities. If an axolotl loses a leg, it doesn’t just grow back a stump of scar tissue; it perfectly reconstructs the bone, muscle, and nerves until the limb is indistinguishable from the original. This process is so efficient that scientists have observed them recovering from significant spinal cord injuries that would leave any other vertebrate permanently paralysed. It is as if they possess a biological blueprint that never fades regardless of how many times they are damaged.

The implications for human medicine are staggering and researchers have spent decades trying to unlock the genetic secrets of the axolotl to see if they can be applied to human wound healing. Unlike humans, who form scar tissue to quickly seal a wound, the axolotl’s cells at the site of an injury revert to a stem-cell-like state and begin the complex task of rebuilding lost structures. This ability to regenerate complex tissues without scarring is the holy grail of regenerative biology and could one day lead to breakthroughs in treating everything from organ failure to traumatic brain injuries. It is a deeply humbling thought that a smiling, pink amphibian found in the ancient lake beds of Mexico holds the keys to a medical revolution. We must ensure the survival of this critically endangered species if we ever hope to fully understand the miracle of its self-healing body.

Bees Use Sun Navigation

The honeybee is a marvel of tiny engineering, possessing the incredible ability to navigate vast distances and return to its hive using the sun as a fixed compass. Even on cloudy days when the sun is completely hidden from human eyes, bees can detect the polarisation of light through the clouds to determine its exact position in the sky. This sophisticated internal GPS allows them to communicate the location of distant flower patches to their nestmates through a highly coordinated “waggle dance.” By adjusting the angle of their dance relative to the sun’s position, they can tell other bees exactly which direction to fly and how far the journey will be. This level of spatial awareness and communication is truly remarkable for a creature with a brain no larger than a tiny grain of sugar.

This reliance on solar navigation means that bees are essentially master astronomers of the insect world, accounting for the sun’s movement across the sky as time passes during their foraging trips. If a bee spends several hours at a flower patch, it will automatically adjust its return flight path to compensate for the fact that the sun has shifted. This ability to integrate time and space suggests a level of cognitive complexity that we are only just beginning to understand in invertebrates. Their survival depends on this pinpoint accuracy because a bee that gets lost is a bee that cannot contribute to the survival of the colony. It is a beautiful example of how nature provides even the smallest creatures with the tools they need to perform monumental tasks. The humble honeybee proves that you don’t need a large brain to be one of the world’s most gifted navigators.

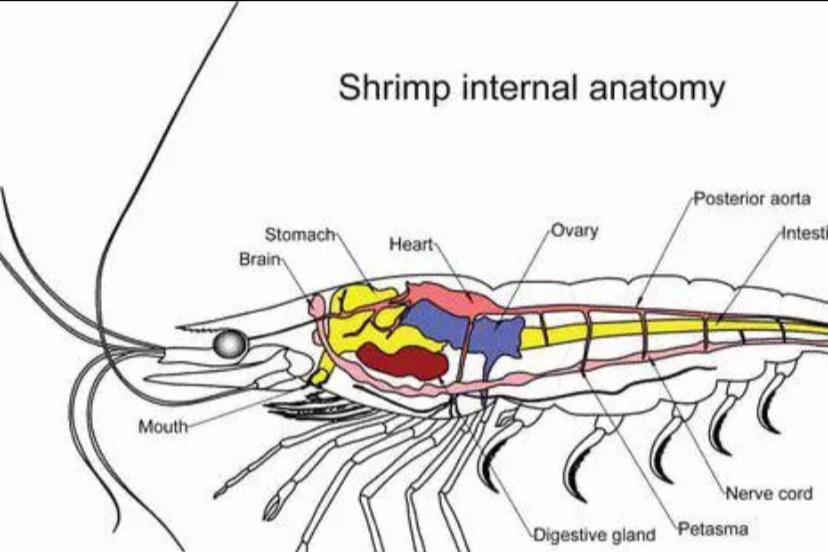

Shrimp Have Heart Heads

In one of the most bizarre instances of anatomical placement in the animal kingdom, a shrimp’s heart is located entirely within its head. This arrangement is part of a larger cephalothorax structure, where the head and the thorax are fused together and protected by a single hard shell called a carapace. Because their vital organs are clustered so closely together in the front of their bodies, a shrimp is essentially “front-heavy” when it comes to its biology. This compact design allows the rest of its body to be composed almost entirely of powerful muscles used for swimming and rapid escapes from predators. It is a highly efficient way to organize a body when your primary goal is to be quick and agile in a crowded underwater environment.

Having a heart in the head might sound risky, but it is actually well-protected by the thickest part of the shrimp’s exoskeleton. This circulatory system is also “open,” meaning their blood which is a clear or yellowish fluid called hemolymph—flows freely through the body cavity rather than being contained within a closed network of veins and arteries. The heart pumps this fluid directly over the internal organs to provide them with oxygen before it collects back near the gills to be re-oxygenated. It is a fascinatingly simple yet effective system that has allowed shrimp to thrive in every ocean on the planet for hundreds of millions of years. This quirky bit of trivia reminds us that there are no set rules for where a heart should beat, as long as it keeps the life-force moving through the creature.

Narwhals Possess Sensory Tusks

The narwhal is often called the “unicorn of the sea” because of the long, spiralling tusk that protrudes from its head, but this feature is actually a highly sensitive tooth rather than a simple weapon. For centuries, people believed these tusks were used for duelling or breaking ice, but recent scientific studies have revealed that they are actually packed with millions of nerve endings. The tusk acts like a massive sensory probe that can detect changes in water temperature, pressure, and even the saltiness of the surrounding ocean. This allows the narwhal to navigate the treacherous, shifting ice floes of the Arctic and locate the specific types of fish it likes to eat. It is an incredible example of an external organ functioning as a high-tech environmental sensor.

The tusk is almost exclusively found on males and can grow up to ten feet in length, yet it is surprisingly flexible and can bend significantly without breaking. Because the nerves are exposed directly to the seawater through tiny pores in the tusk’s surface, the narwhal is essentially “tasting” the ocean as it swims. This sensory input is likely vital for finding mates and migrating through one of the most hostile environments on Earth. While they do occasionally use their tusks to tap and stun small fish, their primary purpose is clearly more about information than aggression. It is a wonderful reminder that nature’s most flamboyant features often serve a practical, hidden purpose that is far more complex than we first imagine. The narwhal’s tusk is not just a crown but a sophisticated antenna for the deep, cold secrets of the north.

Butterflies Taste With Feet

While humans rely on the delicate receptors of the tongue to enjoy a meal, the butterfly has evolved a far more tactile approach by placing its taste sensors directly on its feet. These sensors, known as chemoreceptors, are designed to detect the chemical signatures of various plants the moment the insect lands upon a leaf. This is a critical survival mechanism because it allows the female butterfly to determine instantaneously whether a particular plant is the correct host for her eggs. If she lands on a leaf that contains the right nutrients for her future caterpillars, she will receive a chemical “green light” through her legs and begin the process of laying. It is a remarkably efficient way to navigate a world filled with thousands of different plant species, many of which could be toxic to her offspring.

Beyond the practicalities of reproduction, this foot-based tasting system helps the butterfly locate high-quality nectar to fuel its own flight. When they land on a flower, they are essentially “walking on their food” and can gauge the sugar content before they even unfurl their long, straw-like proboscis to drink. This adaptation saves them precious energy and reduces the time they spend exposed to predators while feeding. It is quite a strange thought to imagine experiencing the flavour of a garden simply by strolling through it, yet for the butterfly, this is the primary way it interacts with the chemistry of its environment. Their delicate legs are not just for standing but serve as highly sophisticated laboratory equipment that guides every major decision in their short and vibrant lives.

Lyrebirds Mimic Chainsaws Perfectly

The superb lyrebird of Australia is widely regarded as the most accomplished acoustic artist in the animal kingdom due to its nearly flawless ability to mimic almost any sound it hears in the forest. While they primarily use their complex syrinx to replicate the songs of other bird species to impress potential mates, they have also been known to incorporate human-made noises into their repertoire. There are famous recordings of lyrebirds perfectly imitating the sounds of camera shutters, car alarms, and even the guttural roar of chainsaws used by loggers. This mimicry is so accurate that it can easily fool both other animals and human observers, creating a surreal soundscape where the mechanical and the biological are indistinguishably blended together.

This incredible talent is more than just a party trick because it serves a vital role in the social and reproductive lives of the males. By demonstrating a vast and varied “vocabulary” of sounds, a male lyrebird proves to females that he is experienced and has lived long enough to encounter many different things in his environment. Their brains are specially wired to process and store these auditory patterns, allowing them to recall and perform them with staggering precision during the breeding season. It is a poignant reflection of our impact on the world that a bird meant to sing the songs of the rainforest has now added the sounds of the industry that threatens its habitat to its daily performance. This mimicry is a living record of the changing environment, captured in the throat of one of nature’s most gifted performers.

Owls Have Tube Eyes

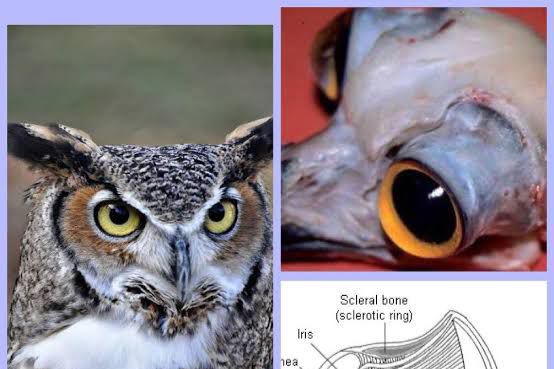

We often think of eyes as being spherical globes that can rotate freely in their sockets, but an owl’s eyes are actually shaped like elongated tubes that are held in place by bony structures called sclerotic rings. This unique shape is the reason why owls cannot move their eyes at all and must instead turn their entire heads up to 270 degrees to change their field of vision. These “eye tubes” are an evolutionary trade-off that allows the owl to have massive retinas and lenses, which are essential for capturing every available photon of light during their nocturnal hunting expeditions. Because the eyes are so large and fixed, they function like powerful telephoto lenses, providing the bird with incredible binocular vision and depth perception for spotting tiny prey from great distances.

The internal structure of these tube-shaped eyes is packed with light-sensitive rod cells, giving owls a level of night vision that far exceeds almost any other creature on the planet. However, because their eyes are so specialised for distance and low light, they are actually quite farsighted and struggle to see things that are right in front of their beaks. To compensate for this close-up “blind spot,” they use tiny, hair-like feathers on their beaks and feet called cristae to sense their surroundings and feel their prey. It is a fascinating example of how nature can completely redesign a standard organ to meet a specific environmental challenge. The owl’s fixed, tubular gaze might look intense or even eerie to us, but it is the secret to their success as one of the world’s most efficient and silent aerial predators.

Polar Bears Have Black Skin

The vast, white expanses of the Arctic provide the perfect backdrop for the polar bear’s camouflage, yet beneath that thick coat of snowy fur lies a surprising secret: their skin is actually jet black. This dark pigmentation is a crucial adaptation for life in one of the coldest environments on Earth because black surfaces are far more efficient at absorbing and retaining heat from the sun. While their fur appears white to the human eye, it is actually translucent and hollow, acting like a collection of tiny fibre-optic cables that funnel sunlight directly down to the dark skin below. This ingenious solar heating system allows the bears to stay warm even when the air temperature drops well below freezing, supplementing their thick layer of insulating blubber.

If you were to shave a polar bear, it would look much more like a large, dark shadow than the iconic white predator we see in nature documentaries. The fur only appears white because the hollow hairs scatter and reflect visible light, much like the way snow or clouds appear white despite being made of clear water or ice. This dual-purpose setup provides the bear with both the perfect disguise for stalking seals on the ice and a highly efficient way to harvest energy from the weak Arctic sun. It is a masterclass in biological engineering that proves things are rarely as they seem in the wild. This hidden darkness is a vital part of the bear’s survival kit, showing us that even the most famous features of an animal often have a secondary, more practical function hidden just beneath the surface.

Elephants Cannot Actually Jump

Despite being some of the most powerful and majestic creatures on the planet, elephants hold the unique distinction of being the only mammals that are physically incapable of jumping. Their massive skeletal structure is designed to support several tonnes of weight, and their legs function much like solid pillars to distribute this immense pressure evenly across the ground. Unlike smaller mammals that have spring-like tendons and joints capable of launching them into the air, an elephant’s leg bones are all pointed downwards and they lack the flexible “spring” in their ankles required for a vertical leap. For an animal of this size, the risk of injury from a fall would be catastrophic, so evolution has prioritised stability and steady movement over acrobatic agility.

This physical limitation does not mean that elephants are slow or clumsy, as they can reach surprisingly high speeds when charging and are incredibly sure-footed on difficult terrain. They always keep at least one foot on the ground at all times, even when they are moving quickly, which technically means they never truly “run” in the way a horse or a dog does. Their feet are also equipped with a thick pad of fatty tissue that acts like a shock absorber, allowing them to walk almost silently despite their enormous bulk. This steady, grounded approach to life has served them well for millions of years, allowing them to navigate vast distances in search of water and food without putting unnecessary strain on their bodies. It is a gentle reminder that power and grace do not always require leaving the ground, and that there is a certain dignity in being firmly rooted to the earth.

Reindeer Eyes Change Colour

In one of the most remarkable seasonal transformations in the animal kingdom, the eyes of the Arctic reindeer actually change colour from a shimmering gold in the summer to a deep, vivid blue in the winter. This is not just a cosmetic change but a functional adaptation to the extreme lighting conditions found in the polar regions. During the summer months, when the sun never sets, the golden colour helps reflect the intense light and protects the reindeer’s retinas from damage. However, when the endless darkness of winter arrives, the pressure inside the eye increases and causes the structure of the tapetum lucidum, the reflective layer behind the retina to compress. This change in structure alters the way light is reflected, shifting the colour to blue and significantly increasing the eye’s sensitivity to low light.

This biological “blue shift” allows reindeer to detect the faint ultraviolet light that is abundant in the Arctic winter, helping them spot predators like wolves and find lichen buried deep beneath the snow. By being able to see in a spectrum that is invisible to most other mammals, they gain a significant advantage in a landscape where every advantage counts. This internal recalibration is a perfect example of how animals can physically alter their own anatomy to cope with the changing rhythm of the planet. It is a beautiful and highly sophisticated solution to the problem of surviving in a land of extremes, proving that the reindeer is far more than just a symbol of the festive season. Their shifting eyes are a window into a world of hidden light and shadow that we can only imagine, showing us that nature is always finding new ways to see through the dark.

It is fascinating to reflect on how our understanding of the natural world often hinges on the observations of a few dedicated researchers or the sheer volume of a single factory’s output.

Like this story? Add your thoughts in the comments, thank you.