1. Hedy Lamarr – The Screen Siren Who Invented Wi‑Fi’s Grandmother

Hedy Lamarr, used her time off‑screen to tinker with gadgets and engineering breakthroughs. In 1942, with composer George Antheil, she patented a frequency‑hopping communication system using piano‑roll synchronicity to guide torpedoes securely by jumping radio frequencies, thwarting jamming. The U.S. Navy initially ignored it; they thought it too bulky but the idea wasn’t lost. Decades later, components of that system became vital to military communication during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and eventually inspired Wi‑Fi, Bluetooth, and GPS technologies.

In 1997, Hedy and Antheil received the EFF Pioneer Award for their vision and in 2014 Hedy was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame. Yet, throughout her life she was more often praised for her beauty than her brain and her true role in tech was largely a late‑arriving footnote. In recent retrospectives like Vanity Fair’s 2021 portrait and the documentary Bombshell: The Hedy Lamarr Story, she’s finally remembered not just as a glamorous figure, but as a brilliant problem‑solver.

2. Sybil Ludington – The Midnight Rider Who Time Forgot

At just 16 years old, Sybil Ludington is said to have embarked on a harrowing 40‑mile ride on April 26, 1777, in a torrential storm to summon militia forces after the British attacked Danbury, Connecticut. But historians caution that the first mention of this ride appeared only in the mid‑1800s, and details are murky. Critics also suggest the story was embellished decades later, with evidence largely passed through family memoirs around 1907.

Yet despite the uncertainty, Ludington’s tale began to emerge in public consciousness during the twentieth century; a statue was erected in 1961, and a U.S. postage stamp honored her in 1975. Still, she never claimed the spotlight of Paul Revere; her ride was nearly erased until folklore and feminist historians reclaimed her legacy. We may never know if every word of her ride is true, but the symbolism of a teenage girl racing through the dark for freedom endures.

3. Claudette Colvin – The First Teen Who Sat Before Rosa Parks

On March 2, 1955, fifteen-year-old Claudette Colvin boarded a Montgomery bus and refused to give up her seat nine full months before Rosa Parks’s more famous moment. As a member of the NAACP Youth Council, she was prepared: when ordered to move, she declared it her constitutional right. Arrested for assaulting an officer, she later became a central witness in Browder v. Gayle, the case that abolished bus segregation nationwide.

But the civil‑rights leadership distanced itself. Colvin, a pregnant teenager, wasn’t seen as a “safe” face. She faced ostracism and her story faded even though scholars point out “if it weren’t for that case…and continued efforts…, we might still be marching”. Not until recent years have historians and media reclaimed her story, even securing expungement of her juvenile record in 2021. Colvin reminds us that heroes don’t all wear crowns, some hold seats firmly.

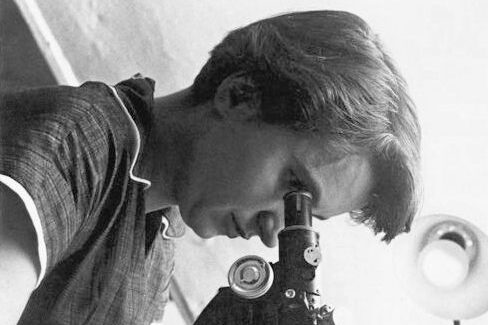

4. Rosalind Franklin – The Crystallographer Who Saw the Blueprint of Life

Rosalind Franklin’s journey begins in the hushed corridors of King’s College London in early 1951, where she meticulously captures the first clear X-ray images of DNA fibers. By May 1952, her iconic “Photo 51” spoke volumes even before Watson and Crick recognized its clarity. This image revealed the helical nature of B-form DNA and even hinted at complementary base pairs. Her deep chemical instincts showed that phosphate backbones lay on the exterior, countering then-popular beliefs.

Yet, when Watson and Crick published their model of the double helix in April 1953, they leaned heavily on her unpublished insights, some shared without her knowledge. She passed away tragically in April 1958, and by 1962 the Nobel Prize was awarded to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins nearly erasing Franklin from the narrative. But scholars like Nathaniel Comfort emphasize she was “two steps away” from the full model herself. In recent decades, thanks to feminist historians and renewed attention, she’s now honored as the “dark lady of DNA”.

5. Lise Meitner – The Physicist Who Co‑Named Nuclear Fission

Lise Meitner’s born in Vienna in 1878, she became the second woman ever to earn a physics doctorate from the University of Vienna. She went on to thrive in Berlin’s Kaiser Wilhelm Institute, collaborating with Otto Hahn to pioneer radiation research and later, to unravel the secrets of nuclear fission. She was also the first woman to become a full professor of physics in Germany. When Hahn and Strassmann identified barium among neutron‑bombarded uranium samples in 1938, it was Meitner then exiled in Sweden who, with her nephew Otto Frisch, interpreted the data and coined the term “nuclear fission”.

Yet when the 1944 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded, only Hahn was honored even though he largely relied on Meitner’s insights. Historians attribute this oversight to the Matilda effect, the systematic bias that denies women credit for their achievements. Additionally, her Jewish heritage forced her to flee Nazi Germany just before the Anschluss, severing her from major publications and political favor. She lived out her days honored by scientific peers element 109, “meitnerium,” bears her name, and Einstein dubbed her the “German Marie Curie” but her Nobel omission speaks volumes.

6. Alice Guy‑Blaché – Cinema’s First Female Director

In 1894 Paris, a young secretary at Gaumont named Alice Guy was handed a camera to capture everyday scenes and she crafts what’s widely considered the first narrative film, The Fairy of the Cabbages (1896), and goes on to direct around 600 silent shorts by 1906. She rose to head of production at Gaumont, then co-founded her own studio, Solax, in New Jersey making her the first woman studio-owner and one of the first global directors.

Despite her groundbreaking innovations in editing, special effects, color tinting, and even early syncsound experiments, Alice’s work was slowly written out of the history books. By the 1920s and ’30s, histories of film failed to credit her; even Gaumont’s own accounts positioned fiction filmmaking only from 1906 onward, ignoring her earlier efforts. Many of her films were lost or misattributed to male counterparts. It wasn’t until the 2018 documentary Be Natural: The Untold Story of Alice Guy‑Blaché narrated by Jodie Foster that her place in cinema’s foundation was firmly reclaimed.

7. Ching Shih – The Pirate Queen Who Commanded an Empire at Sea

Ching Shih, also known as Zheng Yi Aso, was born as Shi Yang around 1775 in Guangdong, China, began her life in hardship and obscurity rumored to have worked on a floating brothel as a teenager. In 1801, she married Zheng Yi, a pirate lord, and together they built the Red Flag Fleet. By 1805 it had swelled to about 400 junks and 40,000–60,000 pirates under their joint command. After Zheng Yi’s death in 1807, Ching Shih assumed full leadership empowering the fleet, marrying her adopted son Cheung Po Tsai to consolidate power, then enacting a strict code of conduct: disobedience led to beheading, rape of captives meant death, consensual relations had strict fallout, and pirates were punished for mistreatment of women.

Under her command, the fleet dominated the South China Sea, fought and defeated the Qing navy, secured tribute from foreign powers like the East India Company, and even repelled joint Sino-Portuguese offensives. At its peak, some records suggest she led up to 1,800 ships and 80,000 able soldiy. After suffering naval setbacks, including the battles at the Tiger’s Mouth (1809–1810), she negotiated amnesty with the Qing government in 1810 allowed to keep her loot, retire peacefully, and even establish a gambling house in Macau, where she lived until her death in 1844. Ching Shih’s name faded from Western histories but in recent years historians have reclaimed her legacy as the world’s most successful female pirate and a master strategist on the seas.

8. Mary Anning – The Fossil Hunter Who Shaped Paleontology

Born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, Dorset, England, Mary Anning grew up poor, her father a cabinetmaker who hunted fossils along the Jurassic Coast to support the family. At just twelve, she discovered the first complete ichthyosaur skeleton; as an adult, she unearthed the first two plesiosaur skeletons, the first pterosaur found in Britain, and fish fossils that would challenge prevailing ideas about prehistoric life. She also pioneered the study of coprolites fossilized feces opening vital windows into ancient ecosystems.

Despite her groundbreaking finds, Anning was excluded from the scientific institutions of her time. The Geological Society of London wouldn’t admit women, and male researchers often took credit for her work, publishing papers based on specimens she sold or discovered. Only after her death in 1847 did the scientific community begin to acknowledge her contributions she received a stipend from the Geological Society, an honorary museum membership, and became famous enough in 2014 to be the subject of a Google Doodle.

9. Sophie Scholl – The University Student Who Whispered Truth

Sophie Scholl was a 21‑year‑old student at the University of Munich when the horrors of Nazism became too heavy to bear. Alongside her brother Hans and friends, she helped form the White Rose, a group that distributed leaflets calling out the Nazi regime’s cruelty. On February 18, 1943, daring to scatter their final pamphlet, she was seen tossing leaflets in the foyer and arrested moments later by university staff who denounced her.

Just four days later, Sophie was tried for treason in a show trial and executed by guillotine on February 22, 1943 as her final act a stand for justice and conscience. In the decades that followed, though remembered in Germany with coins, stamps, and films, her heroism briefly drifted outside public consciousness. It wasn’t until retrospectives, documentaries, and educational projects revived her legacy that many beyond Germany came to know her story.

10. Nannie Helen Burroughs – The Educator Who Built Black Girls’ Futures

Born to formerly enslaved parents in 1879, Nannie Helen Burroughs became a powerhouse of advocacy in Washington, D.C., founding the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1909. Her aim wasn’t just education, it was empowerment, teaching domestic science alongside leadership. Her speech “How the Sisters Are Being Hindered from Helping,” at the 1909 National Baptist Convention in Virginia, outrightly won her fame and recognition.

As a prominent speaker and religious leader, she tackled both racial and gender constraints, also organizing Black women within the National Baptist Convention and serving on Hoover-era policy committees. Despite her broad impact, history books often sidelined her, focusing elsewhere on the civil‑rights struggle. It wasn’t until posthumous honors of a national historic landmark, a renamed school, even a dedicated street lifted her profile back toward the light.

11. Henrietta Lacks – The Unwitting Mother of Modern Medicine

Henrietta Lacks, a Black tobacco farmer and mother from Roanoke, Virginia, unknowingly changed medicine forever when cells from her cervical tumor taken without consent in 1951, at Johns Hopkins were used to create the immortal HeLa cell line. These cells have since fueled breakthroughs from the polio vaccine to cancer and AIDS research.

Lacks remained anonymous for decades; neither she nor her family was informed or compensated until much later. Only in the 2010s did the narrative begin to shift with Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, ethical agreements, legal settlements, even a Congressional Gold Medal finally anchored her name to the science she made possible. Schools, research buildings, and statues now bear her name, reminding us that behind every cell line is a real human being whose story matters as much as the science it fuels.

12. Amelia Boynton Robinson – The Heart of Selma’s March

Amelia Boynton Robinson, a teacher turned activist, became a pivotal figure in the 1965 Selma voting rights marches. As one of the earliest SNCC field workers, she organized grassroots campaigns to register Black voters in Alabama. On Bloody Sunday, March 7 1965, she was beaten unconscious on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and an image of her on the ground shocked the nation and helped catalyze the Voting Rights Act.

Despite this, her contributions have often remained overshadowed by larger narratives centering other leaders. It was only much later over her long life that she was honored with recognition including the Martin Luther King Jr. Freedom Medal in 1990. Her role reminds us that true movements are built on the shoulders of many steadfast souls, whose names like hers deserve our memory.

13. Ada Lovelace – The First Coder Before Computers Existed

Ada Lovelace, daughter of Lord Byron and a gifted mathematician, collaborated in the 1840s with Charles Babbage on his Analytical Engine probing its potential with detailed notes that included the first algorithm meant for machine execution. Though Babbage built mere blueprints, it was Lovelace’s insight that earned her the title “first computer programmer.” She also envisaged computing beyond arithmetic, imagining music and art from machines.

Her contributions faded into obscurity until feminist scholars resurrected her legacy in the late 20th century. Today, the programming language Ada, women’s coding grants, and Ada Lovelace Day all stand as monuments to a visionary woman whose imagination glowed long before electronic computers.

This story #Herstory Restored: 13 Forgotten Women Who Shaped the World was first published on Daily FETCH