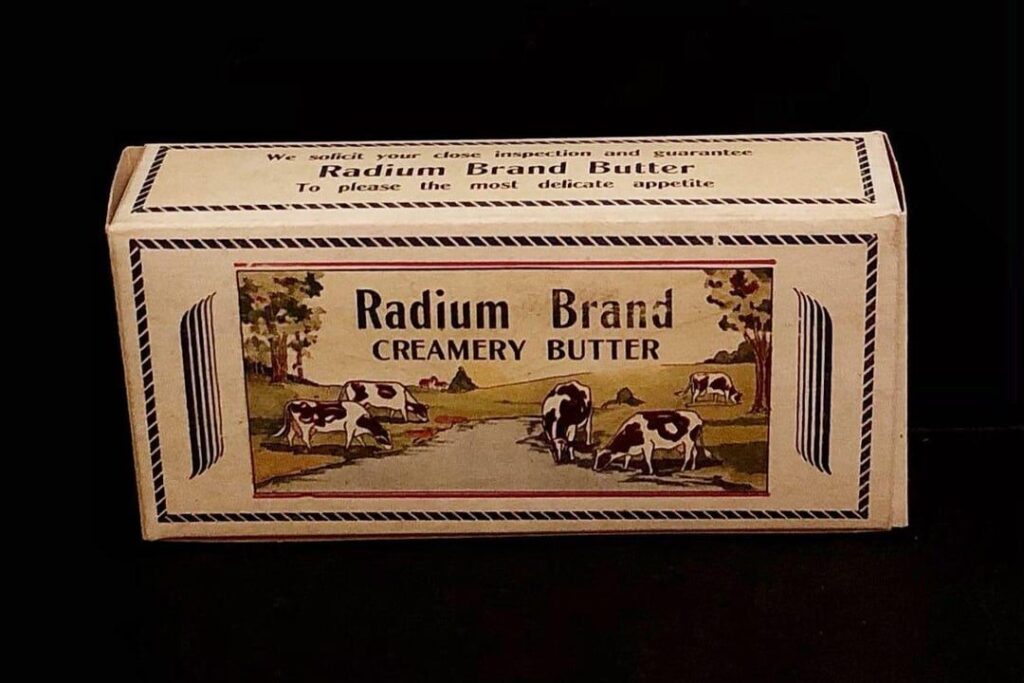

1. Radiation as a Health Booster

In the mid-20th century, radiation was often seen as a beneficial force. Products containing radioactive materials were marketed for their supposed health benefits. For instance, radium-infused water and cosmetics were popular, despite the dangers we now associate with radiation exposure. This belief persisted until the harmful effects became undeniable, leading to increased regulation and public awareness.

Today, we understand that radiation can cause serious health issues, including cancer. The shift in perception highlights the importance of scientific research and caution when introducing new technologies or substances into everyday life.

2. Predators as Pests

During the 1950s and 1960s, predators like wolves and coyotes were often viewed as threats to livestock and human safety. Government programs aimed to eradicate these animals, leading to significant declines in their populations. For example, in the United States, predator control programs resulted in the near elimination of wolves from many areas.

Modern conservation efforts recognize the crucial role predators play in maintaining ecological balance. Reintroduction programs have helped restore predator populations, leading to healthier ecosystems.

3. Littering as Normal Behavior

In the post-war era, consumerism surged, and disposable products became commonplace. Littering was widely accepted, with little public concern for its environmental impact. Roadsides and public spaces were often strewn with trash, reflecting a lack of awareness about pollution. Over time, environmental campaigns and legislation have transformed public attitudes toward littering. Today, there is greater emphasis on waste reduction, recycling, and environmental stewardship. This shift demonstrates how societal values can evolve to promote more sustainable practices.

4. Widespread Use of DDT

DDT, a powerful pesticide, was extensively used in the 1950s and 1960s to combat insect-borne diseases and agricultural pests. It was sprayed in neighborhoods, parks, and even on children, with little understanding of its long-term effects. The publication of Rachel Carson’s “Silent Spring” in 1962 brought attention to the environmental and health risks associated with DDT, leading to increased scrutiny and eventual bans.

The DDT experience underscores the importance of evaluating the environmental and health impacts of chemical use. It serves as a cautionary tale about the unintended consequences of widespread chemical application without adequate research and regulation

5. Feeding Wild Animals

In the mid-20th century, feeding wild animals in national parks was a common and even encouraged activity. Visitors would often feed bears and other wildlife, believing it was harmless fun. However, this practice led to animals becoming dependent on human food, altering their natural behaviors and increasing the risk of dangerous encounters. The National Park Service struggled to prevent visitors from feeding bears, even as it had previously encouraged the animals to congregate in areas where visitors could watch them eat garbage generated by park hotels.

Today, feeding wild animals is discouraged or prohibited in many parks. Authorities recognize that it can harm animals by disrupting their natural foraging habits and increasing their reliance on humans. This shift reflects a broader understanding of the importance of allowing wildlife to remain wild for their safety and ours.

6. Suppressing All Fires

During the 1950s and 1960s, the prevailing belief was that all wildfires were harmful and should be suppressed immediately. The U.S. Forest Service implemented the “10 a.m. policy,” aiming to extinguish every fire by 10 a.m. the day after it was reported. This approach ignored the ecological role of fire in maintaining healthy ecosystems.

Over time, scientists recognized that fire plays a crucial role in certain ecosystems by clearing dead material, promoting new growth, and maintaining biodiversity. This led to a shift in policy, with controlled burns and allowing some natural fires to burn under supervision becoming accepted practices. This change highlights the importance of understanding natural processes rather than attempting to control them entirely.

7. Embracing Plastic

In the post-war era, plastic was hailed as a miracle material. Its versatility and low cost led to widespread use in various products, from household items to packaging. The environmental impact of plastic waste was not a significant concern at the time. However, by the 1960s, plastic debris in the oceans was first observed, marking the beginning of awareness about its environmental problems.

Today, the environmental toll of plastic is well-documented. Plastic pollution affects marine life, enters the food chain, and contributes to long-term environmental degradation. Efforts are now underway to reduce plastic use, promote recycling, and develop biodegradable alternatives. This evolution in understanding underscores the need to consider the long-term impacts of new materials.

8. Accepting Smog as Progress

In the booming industrial cities of the 1950s and 1960s, smog and air pollution were often seen as signs of economic progress. Cities like Los Angeles and New York experienced frequent smog events, yet the health risks were largely overlooked. In 1966, New York City experienced a severe smog episode that lasted several days, leading to increased hospital admissions and an estimated 168 deaths.

Public awareness of the health hazards associated with air pollution grew, leading to environmental activism and the implementation of air quality regulations. Legislation such as the Clean Air Act was enacted to address pollution and protect public health. This shift illustrates how public perception and policy can change in response to environmental challenges.

9. Wetlands as Wastelands

In the mid-20th century, wetlands were often viewed as useless swamps that needed to be drained for development. This perspective led to widespread destruction of these ecosystems to make way for agriculture, housing, and infrastructure. The loss of wetlands had significant environmental consequences, including increased flooding, loss of wildlife habitats, and degradation of water quality.

Today, wetlands are recognized for their vital ecological functions. They act as natural water filters, provide critical habitats for numerous species, and serve as buffers against storms and flooding. Conservation efforts now focus on protecting and restoring wetlands to preserve their ecological benefits and biodiversity.

10. Animals as Unfeeling Beings

During the 1950s and 1960s, it was a common belief that animals did not experience pain or emotions in the same way humans do. This view justified practices in industries and research that would be considered inhumane today. However, scientific advancements have since demonstrated that many animals possess complex nervous systems and exhibit behaviors indicative of pain and emotional responses. For instance, studies have shown that fish are capable of experiencing pain and emotions, challenging previous assumptions about their sentience.

Recognizing animal sentience has led to significant changes in animal welfare laws and ethical standards. There is now a greater emphasis on humane treatment, with regulations in place to ensure the well-being of animals in various settings. This shift reflects a broader understanding and respect for the emotional and physical experiences of animals.

This story 10 Things People Believed About Nature in the ’50s and ’60s That Sound Crazy Now was first published on Daily FETCH